American Federation of Labor facts for kids

|

|

| Abbreviation | A.F. of L. |

|---|---|

| Predecessor | Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions |

| Merged into | AFL–CIO |

| Founded | December 8, 1886 |

| Dissolved | December 4, 1955 (68 years, 11 months and 26 days) |

| Headquarters | New York City; later Washington, D.C. |

| Location |

|

|

Key people

|

Samuel Gompers John McBride William Green George Meany |

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a big group of labor unions in the United States. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886. The A.F. of L. brought together many different unions, especially those for skilled workers. They wanted to support each other and were not happy with another group called the Knights of Labor.

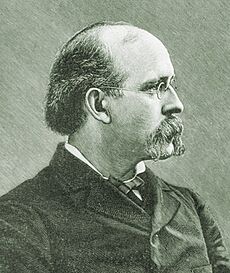

Samuel Gompers was chosen as the first full-time president. He was re-elected almost every year until he passed away in 1924. He became a very important voice for the union movement in the United States. The A.F. of L. grew to be the largest union group. Even when some unions left to form the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in 1935, the A.F. of L. remained strong.

The A.F. of L. and the CIO used to compete a lot. But during World War II and after, they started working together. In 1955, these two big groups joined to create the AFL–CIO. This new organization is still the largest and most important group of labor unions in the U.S. today.

Contents

How the AFL Started

Early Problems with Other Unions

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) began in 1886. It was formed because of disagreements with another large labor group called the Knights of Labor (K of L). The K of L tried to get local unions to leave their main organizations and join the K of L directly. This would have moved money and power away from the individual unions. Another group, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions, also joined to help form the A.F. of L.

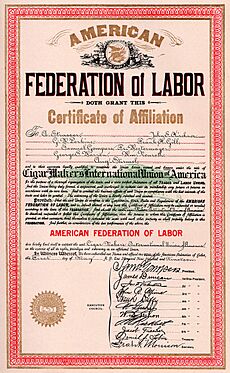

One of the unions involved in this conflict was the Cigar Makers' International Union (CMIU). They were having trouble with a rival union. In January 1886, cigar factory owners in New York City announced a 20 percent pay cut. The CMIU refused, and 6,000 of its members were locked out of their jobs. A four-week strike followed.

Just when the CMIU thought they might win, the Knights of Labor stepped in. They offered to make a deal with the factory owners for lower wages. The only condition was that the rival union's members would be hired. The CMIU leaders were very angry. They asked the national Knights of Labor to investigate. However, the investigation sided with the local Knights of Labor group. Because of this, the American Federation of Labor was formed. It was an alliance of skilled trade unions that wanted to protect themselves from such actions.

In April 1886, leaders from the Cigar Makers and Carpenters unions sent a letter to all national trade unions. They asked them to come to a meeting in Philadelphia. The letter said that some parts of the Knights of Labor were causing "mischief" and "disagreements" in the labor movement. Twenty delegates attended this meeting. They accused the K of L of working with anti-union bosses. They also said the K of L used people who had crossed picket lines or not paid union dues. The group wrote an agreement asking the K of L to stop trying to organize members of other unions without permission.

However, the Knights of Labor did not agree with these demands. They believed that all workers should be united, not separated into different trades. The leader of the K of L, Terence V. Powderly, refused to have serious talks about the issue. The actions of the local Knights of Labor group were supported.

Forming the AFL

Since they couldn't reach an agreement with the Knights of Labor, the leaders of five unions called for a new meeting. This meeting was held on December 8, 1886, in Columbus, Ohio. The goal was to create "an American federation of alliance of all national and international trade unions." Forty-two delegates from 13 national unions and other local labor groups came. They agreed to form the American Federation of Labor.

The new organization would get money from its member unions. Each union would pay a small fee per member each month. The A.F. of L. would be run by annual meetings. Each union would get one delegate for every 4,000 members. The founding meeting decided that the president of the new federation would work full-time and earn $1,000 a year. Samuel Gompers of the Cigar Makers' International Union was elected president. He was re-elected almost every year until he died nearly 40 years later.

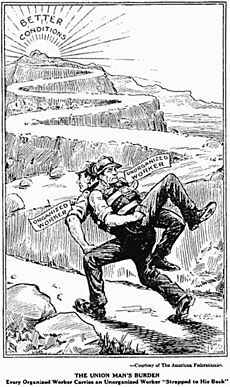

The A.F. of L. focused mainly on improving the pay and working conditions for its members. The founding meeting declared that "higher wages and a shorter workday" were the first steps to making workers' lives better. The group avoided getting involved in politics too much, as they felt it could cause arguments. Their main goal was to help workers with their immediate needs, like better pay and safer jobs. They believed that improving the capitalist system would help workers. This made the A.F. of L. seem like a more moderate choice compared to other, more radical worker groups.

Growing Stronger

Early 1900s Challenges

The A.F. of L. faced a big challenge around 1903. Employers started an "open shop" movement. This meant they wanted to hire people whether they were union members or not. This movement aimed to weaken unions in industries like construction and mining. Between 1904 and 1914, the number of A.F. of L. members went down. This was because companies used legal orders called injunctions to stop strikes. These orders were enforced by the government.

In 1907, the A.F. of L. created the Department of Building Trades, which later became North America's Building Trades Unions (NABTU).

Samuel Gompers believed that unions should "reward their friends and punish their enemies" in politics. This meant supporting politicians who helped workers and opposing those who didn't. Over time, the Republican Party became more aligned with banks and factories. The Democratic Party started to be more supportive of workers. The A.F. of L. became more closely tied to the Democratic Party after 1908.

Working with Businesses

Some unions within the A.F. of L. helped create the National Civic Federation. This group was formed by business owners who wanted to avoid labor disputes. They aimed to do this by encouraging unions and companies to work together. At first, unions were unsure about joining this federation. But their involvement caused some disagreements within the A.F. of L. Socialists, who believed big industries should not be privately owned, criticized this cooperation. However, the A.F. of L. continued its connection with the group, which became less important over time.

Expanding to Canada

By the 1890s, Gompers wanted to create an international federation of labor. He started by expanding A.F. of L. unions into Canada, especially Ontario. He helped the Canadian Trades and Labour Congress with money and organizers. By 1902, the A.F. of L. was a major force in the Canadian union movement.

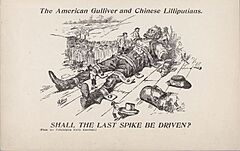

Views on Immigration

The A.F. of L. was strongly against unlimited immigration from Europe. They worried that too many new workers would make it harder to find jobs and lower wages. They were even more against immigration from Asia. They believed Asian cultures could not fit into American society. The A.F. of L. pushed for laws to limit immigration from the 1890s to the 1920s. These laws included the 1921 Emergency Quota Act and the Immigration Act of 1924.

The A.F. of L. also joined efforts to stop child labor. They worked with other reformers to pass laws limiting the employment of children under 14. Their goal was to protect young people and help them attend school.

World War I and After

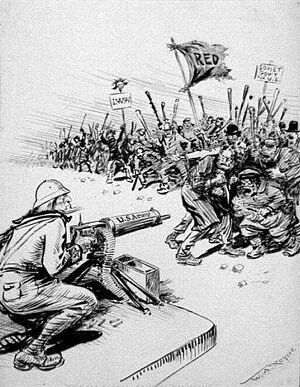

The A.F. of L. and its unions strongly supported the U.S. effort in World War I. They avoided strikes to keep factories running smoothly. This gave them more power to get better conditions for workers. Wages went up as almost everyone had a job during the war. The unions encouraged young men to join the military. They strongly opposed groups that tried to stop recruiting or slow down war production.

To keep factories working well, President Woodrow Wilson created the National War Labor Board in 1918. This board made companies negotiate with unions. President Wilson also appointed A.F. of L. president Gompers to the powerful Council of National Defense.

The A.F. of L. worked closely with the government. They used this chance to grow quickly. They had an agreement with the government to support the war and to work together to stop radical labor groups that were against the war. Gompers even went to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 as an advisor on labor issues.

After the war, in 1919, the A.F. of L. asked the government to release prisoners who had been jailed under wartime laws. President Wilson did not act, but President Warren Harding did.

The year 1919 was a time of big changes for unions. A.F. of L. membership grew from 2.4 million in 1917 to 4.1 million by the end of 1919. The unions tried to keep their gains and called for major strikes in industries like meatpacking and steel. However, these strikes did not succeed. Many African Americans had taken war jobs, and some became strikebreakers in 1919. This led to high racial tensions and major race riots. The economy was strong during the war but then went into a recession. Overall, workers lost some ground, and the A.F. of L. lost some of its influence.

The 1920s

In the 1920s, businesses pushed for "open shops" again. This meant that workers did not have to be union members to get hired. A.F. of L. unions steadily lost members until 1933. In 1924, after Samuel Gompers died, William Green became the new president of the A.F. of L.

The organization supported the progressive presidential candidate Robert M. La Follette in the 1924 election. He only won his home state of Wisconsin. This campaign did not create a lasting political party for workers. After this, the A.F. of L. became even more connected to the Democratic Party, even though some union leaders were Republicans.

The New Deal Era

The Great Depression was a very tough time for unions. Membership dropped sharply. But as the economy started to get better in 1933, union membership also began to rise. President Franklin D. Roosevelt's "New Deal" programs strongly supported labor unions. For example, he made sure that relief programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps did not train skilled workers who would compete with union members.

A very important law was the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, also known as the Wagner Act. This law greatly strengthened unions. It made it easier for workers to join unions and bargain with employers. It also created the National Labor Relations Board, which often ruled in favor of unions. This law helped boost union membership dramatically.

In the early 1930s, A.F. of L. president William Green tried a new way of organizing workers in the car and steel industries. The A.F. of L. started creating "federal labor unions." These unions would organize all workers in an industry, not just skilled craft workers. This was a new approach for the A.F. of L. By 1934, the A.F. of L. had organized 32,500 autoworkers using this model.

However, many leaders of the older, skilled craft unions in the A.F. of L. wanted these new federal unions to join their existing craft unions. They wanted to keep control over their specific trades. This caused a lot of disagreement.

By the 1935 A.F. of L. meeting, William Green and the craft union leaders faced strong opposition. Leaders like John L. Lewis of the coal miners argued that the A.F. of L. was too focused on skilled workers. He believed they were missing the chance to organize millions of semi-skilled workers in factories. In 1935, Lewis led these disagreeing unions to form a new group called the Congress for Industrial Organization (CIO) within the A.F. of L. Both the new CIO unions and the older A.F. of L. unions grew very quickly after 1935.

World War II and Merger

The A.F. of L. stayed closely connected to the Democratic Party in big cities through the 1940s. Its membership grew a lot during World War II. Even after wartime laws supporting labor were removed, the A.F. of L. kept most of its new members. However, despite its strong connections in Congress, the A.F. of L. could not stop the Taft–Hartley Act from passing in 1947. This law limited the power of unions.

In 1955, the A.F. of L. and the CIO finally merged. They formed the AFL–CIO, which was led by George Meany. This merger created the largest and most influential labor federation in the United States.

Historical Problems

Discrimination

In its early years, the A.F. of L. allowed many different kinds of workers to join. This included some radical and socialist workers, and a few semi-skilled workers. Women, African Americans, and immigrants joined in small numbers. However, by the 1890s, the A.F. of L. mostly organized skilled workers in craft unions. This meant it became an organization mainly for white men.

Even though the A.F. of L. said it supported African-American workers, it often treated them unfairly. The A.F. of L. allowed its local unions to be segregated, especially in construction and railroad jobs. This often meant black workers were completely excluded from joining unions and getting jobs in unionized industries.

In 1901, the A.F. of L. pushed Congress to renew the Chinese Exclusion Act. This law stopped Chinese people from immigrating to the U.S. The A.F. of L. also published a pamphlet against Chinese immigration. They also started one of the first organized boycotts. They put white stickers on cigars made by white union workers and told people not to buy cigars made by Chinese workers.

Women in the Workforce

The A.F. of L.'s approach to women workers was similar to its approach to black workers. The A.F. of L. never officially banned women. Sometimes, it even said it supported women joining unions. However, despite these words, it didn't really help women organize. More often, it tried to keep women out of unions and out of the workforce entirely.

At the A.F. of L.'s founding, only two national unions openly included women. Other unions had rules that completely barred women from joining. The A.F. of L. hired its first female organizer, Mary Kenney O'Sullivan, in 1892, but only for five months. They didn't hire another national female organizer until 1908. Women who formed their own unions were often rejected when they tried to join the A.F. of L. Even women who did join unions found them unwelcoming. Meetings were often held at night or in bars, which made it hard or uncomfortable for women to attend. Male union members sometimes interrupted women who tried to speak at meetings.

Generally, the A.F. of L. saw women workers as competition. They thought women might take men's jobs or lower wages. So, they often opposed women working at all. When they did organize women, it was usually to protect men's jobs and earning power, not to improve conditions for women workers. Because of this, most working women stayed outside the labor movement. In 1900, only 3.3% of working women were in unions. By 1910, that number had dropped to 1.5%. It improved to 6.6% by 1920, but women remained mostly outside unions until the mid-1920s.

Attitudes within the A.F. of L. slowly changed because of pressure from organized female workers. Women-led unions started to appear in the early 1900s, like the International Ladies Garment Workers' Union. Women organized independent local unions in places like New York and Chicago. With the help of middle-class reformers and activists, these unions eventually joined the A.F. of L.

Conflicts Between Unions

From the very beginning, unions within the A.F. of L. often argued over which union had the right to represent certain workers. For example, both the Brewers and Teamsters unions claimed to represent beer truck drivers. The A.F. of L. would try to settle these disputes, usually favoring the larger or more powerful union.

To help solve these conflicts, unions within the A.F. of L. formed "departments." For example, the Metal Trades Department helped organize workers in shipbuilding. Local labor councils were also formed in big cities. These councils, made up of all the local unions, became very powerful in some areas.

Historical Achievements

Organizing and Coordination

In its early years, the A.F. of L. worked hard to help its member unions organize. It provided money or organizers. In some cases, like with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers and the American Federation of Musicians, the A.F. of L. even helped create the union itself. The A.F. of L. also used its power to help settle disagreements within unions. It could refuse to grant a charter or even expel a union if necessary. It also encouraged separate unions that represented similar workers to merge.

The A.F. of L. also created "federal unions." These were local unions that were not part of any national union. They were formed in areas where no existing union claimed to represent the workers.

Political Action

Even though Samuel Gompers had contact with socialists, the A.F. of L. adopted a philosophy called "business unionism." This idea focused on how unions could help businesses make profits and contribute to the country's economic growth. It focused on the immediate job-related interests of skilled workers. The A.F. of L. avoided getting involved in bigger political issues.

Employers found that legal orders called labor injunctions were very effective against unions. These orders were first used to stop the Pullman Strike in 1894. The A.F. of L. tried to make "yellow dog contracts" illegal (where workers promised not to join a union). They also tried to limit the courts' power to issue injunctions and to be free from antitrust laws, which were being used to stop unions. However, the courts often overturned any small legislative wins the labor movement achieved.

In the later years of Gompers' leadership, the A.F. of L. focused its political efforts on getting freedom from government control for unions. They especially wanted to stop courts from using injunctions to block the right to organize or strike. They also wanted to prevent antitrust laws from being used to make union actions like picketing, boycotts, and strikes illegal. The A.F. of L. thought they had achieved this with the Clayton Antitrust Act in 1914. Gompers even called it "Labor's Magna Carta." But in 1921, the United States Supreme Court interpreted the Act very narrowly. This meant courts could still issue injunctions against unions.

However, the A.F. of L.'s cautious approach to politics did not stop individual unions from pursuing their own goals. Construction unions supported laws about who could become a contractor and protected workers' pay rights. Railroad and factory unions pushed for workplace safety laws. Unions generally pushed for laws that would provide workers' compensation for injuries on the job.

The A.F. of L. also supported laws to protect women workers. They argued for fewer working hours for women. While some of this was to protect men's jobs, the A.F. of L. also took more selfless actions. From the 1890s, the A.F. of L. strongly supported women's suffrage (the right for women to vote). They often printed articles supporting suffrage in their newspaper.

After Gompers died, the A.F. of L. became less strict about avoiding politics. However, they remained careful. Their ideas for unemployment benefits in the late 1920s were too small to be helpful, as the Great Depression soon showed. The big federal labor laws of the 1930s came from the New Deal. The huge growth in union membership happened after Congress passed the National Industrial Recovery Act in 1933 and the National Labor Relations Act in 1935.

The A.F. of L. did not support or join the large strikes led by John L. Lewis of the United Mine Workers and other unions. After the A.F. of L. expelled the CIO in 1936, the CIO started a big organizing effort. In 1947, when the Taft-Hartley Act was passed, unions became more politically active. To fight this new law, the CIO joined the A.F. of L. in political cooperation. This set the stage for the two groups to merge eight years later, forming the AFL–CIO with George Meany as the new president.

Leadership

Presidents

- Samuel Gompers, 1886–1894

- John McBride, 1894–1895

- Samuel Gompers, 1895–1924

- William Green, 1924–1952

- George Meany, 1952–1955 (later President of the AFL–CIO)

Secretaries

- 1886: Peter J. McGuire

- 1889: Chris Evans

- 1894: August McCraith

- 1897: Frank Morrison

- 1935: Position merged

Treasurers

- 1886: Gabriel Edmonston

- 1890: John Brown Lennon

- 1917: Daniel J. Tobin

- 1928: Martin Francis Ryan

- 1935: Position merged

Secretary-Treasurers

- 1936: Frank Morrison

- 1939: George Meany

- 1952: William F. Schnitzler

State federations

- Pennsylvania Federation of Labor

- Texas State Federation of Labor

See Also

- AFL–CIO

- Labor history of the United States

- Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions

- Industrial Workers of the World

- Knights of Labor

- Labor federation competition in the United States

- Labor unions in the United States

- Western Federation of Miners

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |