Labor history of the United States facts for kids

The history of workers and unions in the United States tells the story of how working people have joined together to improve their jobs, pay, and lives. Since the 1930s, unions have often worked closely with the Democratic Party.

Unions and workers have always faced challenges. They have fought for better pay, shorter work hours, and safer workplaces. Big union groups like the AFL–CIO have grown, changed, and sometimes split apart. The government has also stepped in at different times.

Unlike many other countries, the United States didn't have its own political party just for workers. Instead, both major American parties tried to get union votes, with the Democrats usually being more successful. Unions were a big part of the New Deal coalition that shaped American politics from the 1930s to the 1960s.

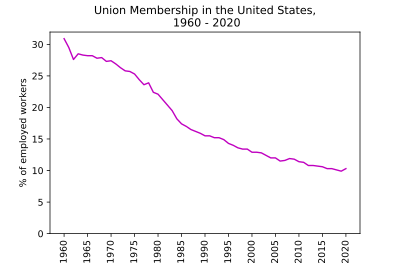

Over the last few decades, the power of unions in the U.S. has gone down.

Contents

- Early Worker Groups (Before 1900)

- Workers and Unions (1900–1920)

- Unions Weaken (1920–1929)

- Unions Grow Stronger (1929–1955)

- Unions Decline (1955–2016)

- Rise in Union Activity (2016 - Present)

- Public-Sector Unions

- Images for kids

Early Worker Groups (Before 1900)

Long before the American Revolution, there were worker disagreements. For example, fishermen went on strike in Maine in 1636, and carmen (people who drove carts) were fined for striking in New York City in 1677. However, these early protests were usually small and didn't lead to lasting worker groups.

Rules and Rights for Workers (1800s)

In the early 1800s, the way people worked changed a lot, especially in big cities. Before, skilled workers often trained as apprentices and then worked for themselves. But with the Industrial Revolution, large factories grew. Many workers became "journeymen," meaning they worked for others without owning their own businesses. This led to more competition among workers.

Because of these changes, workers started to team up to ask for better wages, shorter hours, or improved conditions. These groups were sometimes seen as illegal "conspiracies." Between 1800 and 1850, there were many court cases about this. The main question was whether groups of workers could legally join together to get benefits they couldn't get alone. Most of the time, the courts ruled against the workers.

A very important court case was Commonwealth v. Hunt in Massachusetts in 1842. This decision made it clear that unions were generally legal. It said that workers could join together peacefully to ask for better wages and conditions, as long as their actions weren't harmful to others. This was a big step for worker rights in America.

First Big Worker Groups

The Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen, a union for train workers, started in 1863. It's now part of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters.

The National Labor Union (NLU) was formed in 1866. It was one of the first national groups for workers in the U.S., but it broke up in 1872.

The Order of the Knights of St. Crispin, a union for shoe workers, became very large in the late 1860s. They tried to stop machines and less skilled workers from taking over jobs meant for skilled shoemakers.

Railroad Unions

After 1870, as railroads grew, many unions formed for railway workers. These groups, like the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, usually worked well with railroad companies. They focused on getting insurance and medical help for their members, and setting rules for work, like how seniority worked.

They were not part of the larger AFL union group. In 1916, they helped pass a law called the Adamson Act, which gave train workers 10 hours of pay for an eight-hour workday.

Knights of Labor

The Knights of Labor, started in 1869, was one of the first truly national worker organizations. They believed that all "producers" (workers, farmers, small business owners) should unite. This idea helped them grow very quickly after 1880.

Under their leader, Terence V. Powderly, the Knights tried to make changes through politics and education, not just strikes. They helped create a strong worker culture with activities for families and educational programs.

However, the Knights faced a big challenge in 1886. They were involved in many strikes across the country, including one at the McCormick Reaper Factory in Chicago. During a rally in Chicago, a bomb exploded, killing policemen. This event, known as the Haymarket Riot, was blamed on anarchists (people who believe in no government). Even though the Knights were not anarchists, they were wrongly linked to the violence, which hurt their reputation and caused many members to leave.

American Federation of Labor (AFL)

The American Federation of Labor (AFL) was formed in 1886, led by Samuel Gompers. Unlike the Knights of Labor, the AFL focused on organizing skilled workers into separate unions for each trade (like carpenters or electricians). It didn't directly sign up individual workers, but was a group of many different unions.

The AFL's main goals were to help trade unions grow and to get laws passed, such as stopping child labor and creating a national eight-hour workday. They also supported the idea of a national Labor Day holiday.

Strikes became common in the 1880s, with tens of thousands happening between 1881 and 1905. Most strikes were short and aimed at controlling working conditions or getting fair wages.

The AFL grew steadily while the Knights of Labor faded away. However, the AFL mostly included skilled men and often excluded unskilled workers, African Americans, and women. They sometimes saw women working for lower wages as a threat to men's jobs.

Western Federation of Miners (WFM)

The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) started in 1893. This union often competed with the AFL. The WFM later became the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers and eventually joined the United Steelworkers of America.

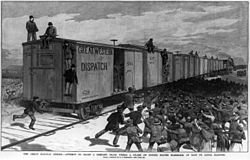

Pullman Strike (1894)

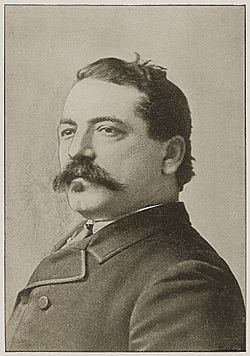

During a tough economic time in the 1890s, the Pullman Palace Car Company cut workers' wages. Workers joined the American Railway Union (ARU), led by Eugene V. Debs. The ARU supported the Pullman workers by asking all railway workers to refuse to handle Pullman cars.

When some workers were punished for this, the entire ARU went on strike in June 1894. Soon, 125,000 workers stopped working. Strikers also caused some damage and riots.

The railroad companies got a court order (an injunction) to stop the boycott. When Debs and other ARU leaders ignored it, President Grover Cleveland sent U.S. Army troops to break the strike, saying it was stopping mail delivery. During the strike, 13 workers were killed. Debs was sent to prison, and the ARU fell apart.

Workers and Unions (1900–1920)

Around this time, American factory workers, especially skilled ones, generally earned more than workers in Europe. However, American industries also had very high accident rates, and the U.S. was the only major industrial country without a system to help injured workers.

From 1860 to 1900, a small number of very rich American families owned most of the country's wealth. This big difference between the rich and the poor led to the rise of groups like populists and socialists, who wanted to change society.

Coal Strikes (1900–1902)

The United Mine Workers union had success in a strike against soft coal mines in 1900. But their strike against hard coal mines in Pennsylvania in 1902 became a national problem. President Theodore Roosevelt stepped in to help find a solution. Miners got higher wages and shorter hours, but their union was not officially recognized as a bargaining group.

Women's Trade Union League

The Women's Trade Union League, started in 1903, was the first group focused on helping working women. It supported the AFL and encouraged more women to join unions. It also worked to get laws passed for minimum wages, limits on work hours, and an end to child labor.

A terrible fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York City in 1911 killed 146 mostly female workers because of poor safety. This event pushed the Women's Trade Union League to demand better safety rules in factories.

Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), also known as "Wobblies," was founded in Chicago in 1905. A key leader was William "Big Bill" Haywood. The IWW was different because it wanted to organize all workers in an industry, not just skilled workers in separate trades. They dreamed of "One Big Union" to get rid of the wage system.

The IWW organized many miners, lumberjacks, and dock workers, especially in the West. In 1912, they led a big strike of textile workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts. The IWW welcomed men and women, and workers of all races and nationalities. At its peak, it had about 150,000 members. However, the IWW was strongly opposed by the government, especially during and after World War I. Many members were jailed or sent out of the country. Even though it faced tough times, the IWW showed that unskilled workers could be organized.

Government and Worker Rights

In 1908, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the Loewe v. Lawlor case (the Danbury Hatters' Case). The Hatters' Union had tried to boycott hats from a non-union company. The Court said the union's actions were illegal under the Sherman Antitrust Act, which was meant to stop businesses from limiting trade. This meant unions could be sued for damages.

The Clayton Act of 1914 was supposed to protect unions from antitrust laws, stating that "the labor of a human being is not a commodity." However, courts often weakened this law, and unions continued to face legal challenges until the Norris-La Guardia Act in 1932.

Between 1912 and 1918, many states passed laws for workers' compensation (money for injured workers), limits on work hours, and minimum wage laws for women.

Colorado Coalfield War

In 1913, the United Mine Workers of America went on strike against the Rockefeller-owned Colorado Fuel and Iron company. This led to the Colorado Coalfield War. The worst event was the Ludlow Massacre in April 1914, when the Colorado National Guard attacked a striker camp, killing women and children. This strike is considered one of the deadliest worker conflicts in American history.

World War I and Workers

During World War I (1914-1918), Samuel Gompers and most unions strongly supported the war effort. They used this support to gain more recognition and higher wages. Strikes were kept to a minimum as jobs were plentiful and wages rose. To keep factories running, President Wilson created the National War Labor Board in 1918, which made companies negotiate with unions. Union membership grew a lot during the war.

Women in the Workforce During WWI

During WWI, many women took jobs that men had left to go to war. Factories making weapons became the biggest employers of American women by 1918. Even though there was some resistance at first, the urgent need for workers meant women were hired in large numbers. They worked in heavy industry, as railway guards, ticket collectors, and even police officers.

The U.S. Department of Labor created a "Women in Industry" group, which helped set standards for women working in war-related jobs. After the war, this group became the U.S. Women's Bureau.

Strikes of 1919

After the war, in 1919, unions tried to keep the gains they had made. The AFL called for many big strikes in industries like meatpacking and steel. However, companies fought back, sometimes saying the strikes were led by Communists. Most of these strikes failed, pushing unions back to where they were around 1910.

Coal Strike of 1919

The United Mine Workers went on strike in November 1919. The government used a wartime law to try and stop the strike, but 400,000 coal workers still walked out. The strike caused a national problem as coal supplies ran low. Eventually, the miners got a 14 percent raise, but it was less than they wanted.

Women Telephone Operators Win Strike

One important strike that was won in 1919 was by women telephone operators in New England. They asked for higher wages because of the rising cost of living. About 9,000 women went on strike, shutting down most phone service. After a few days, they reached a deal for higher wages.

Unions Weaken (1920–1929)

The 1920s were a tough time for unions. Membership and activities dropped a lot. This was due to good economic times, a lack of strong union leaders, and companies and the government being against unions. Strikes became much less common.

The economy was generally good in the 1920s, with stable prices and low unemployment. This meant workers had less reason to join unions. Also, Samuel Gompers, the long-time leader of the AFL, died in 1924, and his replacement was seen as less aggressive.

Companies launched a campaign called the "American Plan" to make unions seem "un-American." Some even used fears of communism to turn people against unions. Courts also made it harder for unions to strike. Employers could force workers to sign "yellow-dog contracts," promising not to join a union, or they would be fired. This was not outlawed until 1932.

Great Railroad Strike of 1922

The Great Railroad Strike of 1922 began in July when railroad repair workers' wages were cut. Many workers went on strike, but the train operators' union didn't join them. The railroads hired new workers to replace the strikers. A federal judge issued a broad order against striking, gathering, and picketing. This order angered unions. The strike eventually ended, but it left bad feelings between the railroads and their workers for years.

Unions Grow Stronger (1929–1955)

The Great Depression and Unions

The stock market crash in October 1929 led to the Great Depression, a time of severe economic hardship. By 1932-33, unemployment reached 25 percent. Unions lost members because workers couldn't afford dues, and strikes against wage cuts left unions poor.

However, the Depression also led to many local protests by unemployed workers. Radical groups like the Communist and Socialist parties often helped organize these protests. In places like Harlan County, Kentucky, coal miners went on strike when their wages were cut, leading to conflicts with company-paid deputies.

Norris–La Guardia Act of 1932

In 1932, Republican President Herbert Hoover signed the Norris–La Guardia Act. This was a big win for unions. It made it harder for courts to issue orders (injunctions) that stopped union activities. It also outlawed "yellow-dog contracts," which forced workers to promise not to join a union. This law was a major change, giving workers more power to organize.

FDR and the National Industrial Recovery Act

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) took office in 1933, he began programs to help the economy. In June, he passed the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA). This law gave workers the right to organize into unions and bargain collectively. It said employers could not stop workers from joining unions or refuse to negotiate with them.

Even though the Supreme Court later said the NIRA was unconstitutional, it inspired many workers to join unions. In 1933 and 1934, the number of strikes jumped significantly as workers fought for union recognition.

AFL: Craft vs. Industrial Unions

The AFL was growing fast, but it had a big disagreement inside: how to organize new members. The AFL traditionally organized "craft unions," meaning workers with specific skills (like electricians) formed their own unions. But some leaders, like John L. Lewis, wanted "industrial unions," which would include all workers in a whole industry (like all workers in car manufacturing), regardless of their specific skill.

This disagreement led to a split. In 1935, Lewis and other leaders formed the Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO) within the AFL. The CIO wanted to organize workers in mass production industries. The AFL refused to give full membership to CIO unions, and in 1938, the AFL kicked out the CIO and its millions of members. The CIO then became a separate group called the Congress of Industrial Organizations. Both the AFL and CIO supported President Roosevelt, but they competed for members.

John L. Lewis and the CIO

John L. Lewis was the powerful president of the United Mine Workers of America (UMW) and the main force behind the CIO. He used the UMW's money to help the CIO organize millions of other industrial workers in the 1930s, including those in steel and auto industries.

Lewis strongly supported President Roosevelt and the New Deal. He told coal miners that "The President wants you to join the Union." The UMW gave a lot of money to Roosevelt's election campaign in 1936.

One of the CIO's biggest successes was the sit-down strike at General Motors in 1936-37. Workers stayed inside the factories, stopping production. This strike helped the CIO's United Auto Workers (UAW) unionize General Motors and other major car companies. However, the sit-down strike also made some middle-class people less supportive of unions.

Unions During World War II

During World War II (1939-1945), union membership grew hugely, from 8.7 million in 1940 to over 14.3 million in 1945. Many women factory workers joined unions for the first time. Both the AFL and CIO supported President Roosevelt and the war effort.

However, John L. Lewis of the United Mine Workers was an exception. In 1943, during the war, he led miners on a strike for higher wages. This led Congress to pass anti-union laws, like the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947.

Women Take New Jobs in WWII

The war sent 16 million American men into the military, creating a huge need for workers. By 1945, 37% of women were working, driven by patriotism and good wages. Many women took jobs traditionally done by men, like steel workers, lumber workers, and bus drivers. The number of women working in factories more than doubled.

At the end of the war, many war-related jobs ended. Some women were replaced by returning soldiers. However, many women stayed in the workforce, and the number of working women in 1946 was still high.

Strikes After World War II

After the war ended in August 1945, there was a wave of major strikes, mostly led by the CIO. Millions of workers in auto, steel, and other industries went on strike. The economy was changing from wartime to peacetime production, and many soldiers were returning home.

The Republican Party used public anger about the strikes to win a big election in 1946. After this, unions took strong actions. The CIO removed Communist leaders from its unions. The AFL also became more involved in politics.

By 1955, the CIO and AFL no longer had major disagreements, and they merged to form the AFL–CIO.

Taft-Hartley Act (1947)

The Labor Management Relations Act of 1947, also known as the Taft–Hartley Act, was passed in 1947. It changed the earlier Wagner Act by adding rules for unions, not just employers. It was passed after many strikes, especially the coal and steel strikes, which people felt were hurting the economy. Unions strongly opposed this law, and President Harry S. Truman vetoed it, but Congress passed it anyway.

The law made certain union actions illegal, like strikes that forced an employer to give specific work to one union's members, and boycotts against businesses not directly involved in a dispute. It also outlawed "closed shops," which required employers to hire only union members. "Union shops," where new workers must join the union within a certain time, were allowed, but with rules.

The Act also allowed individual states to pass ""right-to-work" laws," which make it illegal to require union membership as a condition of employment. Many Southern and Midwestern states have these laws. The law also required unions and employers to give 60 days' notice before striking or taking other economic action.

Historians generally agree that the Taft-Hartley Act didn't destroy unions, but it did make it harder for them to grow, especially in places where they weren't already strong.

Fighting Communism in Unions

The AFL had always been against Communists in the labor movement. After 1945, the CIO, which had some Communist members, also started to remove them. By 1949, many Communist-led unions were kicked out of the CIO. Both the AFL and CIO strongly supported the U.S. government's policies during the Cold War. Leaders like Walter Reuther of the United Automobile Workers worked to remove Communist elements from their unions and supported democratic unionism worldwide.

Unions Decline (1955–2016)

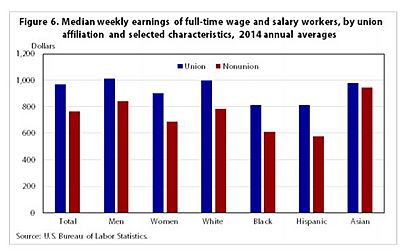

Since the mid-1900s, the American labor movement has steadily declined. In the early 1950s, about one-third of American workers were in unions. By 2012, it was only 11 percent. Unions lost influence, especially in the private sector. This decline has been linked to wages not growing much and to a rise in income inequality.

One reason for the decline is that U.S. laws made unions organize each factory or company individually, rather than organizing whole industries at once. Also, more goods from other countries (like cars from Japan) hurt American industries. Many companies closed or moved factories to Southern states, where unions were weaker. Strikes became less effective because companies could threaten to close factories or move them.

A major blow to unions came in 1981 when President Ronald Reagan broke the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) strike. This event showed that the government was willing to take a tough stance against striking unions, which further weakened the labor movement.

Union membership in private companies dropped sharply. However, after 1970, unions for government employees (federal, state, and local) grew. The 1970s and 1980s also saw a trend toward "deregulation," meaning fewer government rules for industries, which unions often opposed.

AFL and CIO Merge (1955)

The AFL and CIO merged in 1955, ending their past disagreements. This merger was possible because the leaders of both groups, George Meany (AFL) and Walter Reuther (CIO), were willing to compromise. The CIO was no longer as radical as it once was, and the AFL had more members.

The merger helped the new AFL–CIO fight corruption in unions and increase its political power.

Conservative Challenges to Unions

Republicans and business groups often tried to weaken unions, especially after the Taft-Hartley Act in 1947. They focused on showing criminal activity and corruption in some unions, particularly the Teamsters Union. Hearings led by the McClellan Committee targeted Teamsters president James R. Hoffa, making him seem like a public enemy. This led to new laws in 1959, like the Landrum-Griffin Act, which aimed to make unions more democratic.

Civil Rights Movement

The UAW, led by Walter Reuther, played a big role in supporting the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s. However, some older unions favored their white members, leading to government intervention.

Hispanic Workers and United Farm Workers (1960s)

Hispanic workers make up a large part of the farm labor force. However, farm workers were not protected by the main labor laws, so it was hard for them to form unions. This changed in the 1960s with Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, who organized California farm workers into the United Farm Workers (UFW).

Chavez used non-violent methods, and Huerta had strong organizing skills. A major success for the UFW was partnering with another group to organize a strike and consumer boycott against grape growers in California. This lasted over five years and led to better safety and pay for farm workers. The UFW also worked to address the dangers of pesticides. Their efforts led to the creation of an Agricultural Relations Board in California.

Reagan Era (1980s)

Most unions were against Ronald Reagan in the 1980 presidential election. On August 3, 1981, the PATCO union went on strike, trying to shut down commercial airlines. However, federal law forbade this strike. Reagan gave the strikers 48 hours to return to work, or they would be fired. Most did not return, and the strike failed. PATCO disappeared, and this event was a major setback for unions, speeding up the decline in membership in private companies.

After this, unions lost power during the Reagan administration. Wage increases for union workers fell sharply, and the pay gap between union and non-union workers grew.

Decline of Private Sector Unions

By 2011, less than seven percent of workers in private companies belonged to unions. For example, the UAW had over 1.6 million members in 1970, but only 377,000 active members in 2010. Coal mining also saw a huge drop in union members.

Rise in Union Activity (2016 - Present)

In recent years, there has been a new interest in unions. The number of union members increased from 2016 to 2017, and some states saw union growth for the first time in years. Much of this new growth came from younger workers, especially millennials.

Efforts have also been made to extend worker protections to groups like domestic workers and farm workers, who were not covered by older labor laws. Several states have passed new laws to expand their rights.

Teacher Strikes

In 2018, a series of statewide teacher strikes and protests gained national attention. Many of these strikes happened in states where public-employee strikes are illegal, but they were successful. Teachers protested for better pay and school funding in states like Arizona, Oklahoma, and West Virginia.

Unionization in Tech

The relatively new high tech sector, which creates computer hardware and software, has not traditionally been unionized. These are often white-collar jobs with good pay and benefits. However, some tech workers have started to organize to change company practices, such as a walkout at Google in 2018 to protest harassment policies.

One area where union efforts have grown is in the video game industry. Workers have spoken out about "crunch time," where they are expected to work extremely long hours. In February 2020, employees at Kickstarter voted to form a union, becoming one of the first tech companies to do so.

On April 1, 2022, Amazon workers at a warehouse in Staten Island, New York City, voted to form a union. This was the first unionized Amazon workplace in the United States.

Public-Sector Unions

Unions generally didn't focus on government employees in the past because these jobs were often given out based on political connections. However, Post Office workers did form unions, like the National Association of Letter Carriers in 1889.

Early Public Sector Unions

The Boston Police Strike in 1919 was a major event. Governor Calvin Coolidge broke the strike, and the state took control of the police. This event made unions less interested in organizing public sector workers for a while.

However, public school teachers in big cities started forming unions, like the American Federation of Teachers (AFT).

New Deal Era and Public Workers

In the mid-1930s, there were attempts to unionize workers in government programs like the Works Progress Administration. But President Franklin D. Roosevelt, while supporting unions in private companies, was against them for government workers. He believed that collective bargaining for government employees was different and not possible in the same way.

"Little New Deal" Era

Things started to change in the 1950s. In 1958, New York City Mayor Robert Wagner, Jr. issued an order that gave city employees some bargaining rights and allowed their unions to represent all city workers.

By the 1960s and 1970s, public-sector unions grew quickly, covering teachers, police, firefighters, and other government workers. In 1962, President John F. Kennedy issued an order that improved the status of unions for federal workers.

Recent Years for Public Unions

After 1960, public sector unions grew rapidly and helped their members get good wages and pensions. While jobs in manufacturing and farming declined, government employment at the state and local level quadrupled.

In 2009, for the first time, the number of public sector union members in the U.S. was higher than the number of private sector union members.

In 2011, many states faced money problems, and Republican lawmakers tried to reduce the power of public sector unions, especially in Wisconsin. They argued that public unions were too powerful and that generous pensions were too expensive for state budgets.

Images for kids

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |