Haymarket affair facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Haymarket affair |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Great Upheaval | |||

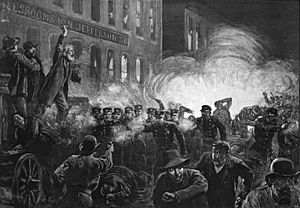

This 1886 engraving was the most widely reproduced image of the Haymarket massacre. It shows Methodist pastor Samuel Fielden speaking, the bomb exploding, and the riot beginning simultaneously; in reality, Fielden had finished speaking before the explosion.

|

|||

| Date | May 4, 1886 | ||

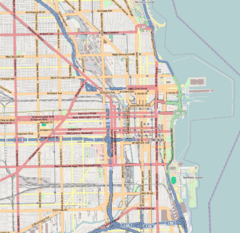

| Location |

41°53′5.6″N 87°38′38.9″W / 41.884889°N 87.644139°W |

||

| Goals | Eight-hour work day | ||

| Methods | Strikes, protest, demonstrations | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

| Casualties and arrests | |||

|

|||

The Haymarket affair was a major event in American labor history. It is also known as the Haymarket massacre or Haymarket riot. This event happened after a bomb exploded at a workers' protest on May 4, 1886. The protest took place at Haymarket Square in Chicago, Illinois, United States.

The rally started peacefully. Workers were supporting a strike for an eight-hour workday. This was one day after a violent event at the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company. There, one person died and many workers were hurt.

During the Haymarket rally, someone threw a dynamite bomb at the police. The police were trying to end the meeting. The bomb blast and shooting that followed caused the deaths of seven police officers. At least four civilians also died. Dozens more people were injured.

After the bombing, there were legal trials that gained international attention. Eight anarchists were found guilty of planning the attack. Evidence suggested one defendant might have built the bomb. However, none of those on trial had thrown it. Only two of the eight were even at Haymarket Square when the bomb exploded.

Seven of the anarchists were sentenced to death. One was given 15 years in prison. Illinois Governor Richard J. Oglesby changed two death sentences to life in prison. Another person died in jail before their execution. The other four were hanged on November 11, 1887. In 1893, Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld pardoned the remaining prisoners. He also criticized how the trial was handled.

The Haymarket Affair is very important in history. It is seen as the start of International Workers' Day, celebrated on May 1. It was also a key moment in the Great Upheaval. This was a time of big social unrest among American workers.

The place where the event happened became a Chicago landmark in 1992. A special sculpture was put there in 2004. Also, the Haymarket Martyrs' Monument was named a National Historic Landmark in 1997. This monument is at the burial site of the defendants in Forest Park.

Contents

Why the Haymarket Affair Happened

After the Civil War, factories and businesses grew very quickly in the United States. Chicago was a major industrial city. Thousands of immigrants from Germany and Bohemia worked there. They often earned about $1.50 a day. American workers usually worked over 60 hours a week, six days a week.

Chicago became a center for workers trying to get better conditions. Employers often fought against unions. They would fire union members or refuse to hire them. They also used spies, hired security, and tried to divide workers. Newspapers often supported the businesses. But labor and immigrant newspapers supported the workers.

Between 1882 and 1886, groups like socialists and anarchists became very active. The Knights of Labor was a large union that grew a lot. They wanted an eight-hour workday. In Chicago, many immigrant workers were part of the anarchist movement. They read the German newspaper Arbeiter-Zeitung. August Spies was its editor. Some anarchists even had weapons and explosives. They believed that fighting the police could start a revolution. They hoped this would lead to a socialist economy.

The Push for an Eight-Hour Workday

In October 1884, a group called the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions met. They decided that May 1, 1886, would be the day for an eight-hour workday. As the date got closer, unions across the U.S. planned a general strike. This strike was to demand the shorter workday.

On Saturday, May 1, thousands of workers went on strike. They attended rallies all over the United States. They sang a song called Eight Hour. The song's chorus said, "Eight Hours for work. Eight hours for rest. Eight hours for what we will."

About 300,000 to half a million workers went on strike across the U.S. In New York City, about 10,000 people protested. In Chicago, the center of the movement, 30,000 to 40,000 workers went on strike. Perhaps twice as many people were in the streets for demonstrations. For example, 10,000 lumber yard workers marched.

On May 3, August Spies spoke to striking workers outside a factory. He told them to "hold together" and "stand by their union." The strike had been mostly peaceful until then. But when the workday ended, some workers rushed to confront strikebreakers. Police fired into the crowd, even though Spies called for calm. Two McCormick workers were killed. Spies later said he was very angry. He believed the police action was meant to stop the eight-hour movement.

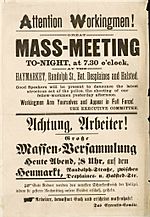

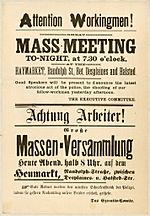

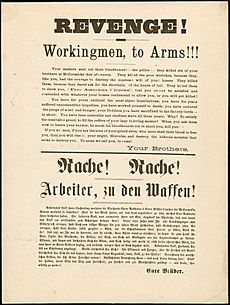

Local anarchists were very upset by this police action. They quickly printed flyers for a rally the next day. The rally was to be at Haymarket Square. The flyers were in German and English. They said the police had killed strikers for business owners. They urged workers to seek justice. The first flyers said, Workingmen Arm Yourselves and Appear in Full Force! Spies said he would not speak if those words were on the flyer. Most of these flyers were destroyed. New ones were printed without the strong words. More than 20,000 of the new flyers were given out.

The Rally and the Bombing

The rally started peacefully on the evening of May 4. It was raining lightly. August Spies, Albert Parsons, and Rev. Samuel Fielden spoke to the crowd. Estimates for the crowd size ranged from 600 to 3,000 people. They spoke from an open wagon near the square. Many police officers watched from nearby.

After Spies spoke, Parsons addressed the crowd. He was the editor of a radical English newspaper. The crowd was so calm that Mayor Carter Harrison Sr. left early. Parsons spoke for almost an hour. Then Rev. Samuel Fielden, a socialist and labor activist, gave a short ten-minute speech. Many people had already left because of the bad weather.

Newspaper reports at the time described the event with strong words. One New York Times article said, "Rioting and Bloodshed in the Streets of Chicago." Another called it "Anarchy's Red Hand." These articles often used negative terms for the strikers.

The Bomb Explodes

Around 10:30 PM, as Fielden was finishing his speech, police arrived. They marched in formation towards the speakers' wagon. They ordered the rally to break up. Fielden insisted the meeting was peaceful.

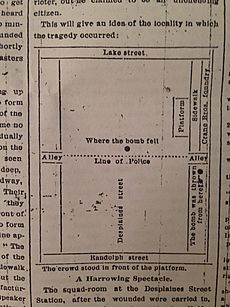

Then, a homemade bomb was thrown. It landed near the police, killing officer Mathias J. Degan. Many other policemen were badly wounded.

Witnesses said that after the bomb, police and demonstrators exchanged gunfire. It is not clear who shot first. Historians say that most sources agree the police fired first. They reloaded and fired again. This killed at least four people and wounded up to 70. In less than five minutes, the square was empty except for the injured.

In total, seven policemen and at least four workers died. Many police deaths were from police gunfire. It is unknown how many civilians were hurt. Many were afraid to seek medical help because they feared arrest.

Aftermath and Public Reaction

After the Haymarket incident, there was a strong crackdown on unions. The "Great Upheaval" of workers' protests ended. Employers gained more control. Workdays went back to ten or more hours.

Many people and businesses supported the police. Thousands of dollars were given to help injured officers. The entire labor and immigrant community, especially Germans, came under suspicion. Police raided homes and offices of suspected anarchists. Many people were arrested, even if they had little to do with the Haymarket Affair. Police searched meeting halls and businesses for eight weeks. They focused on the speakers at the rally and the Arbeiter-Zeitung newspaper.

Newspapers said that anarchist leaders were to blame for the "riot." The public believed this view. Over time, news reports and pictures of the event became more dramatic. The story spread across the country and then worldwide. Business owners, the press, and others agreed that anarchist ideas needed to be stopped.

Unions like The Knights of Labor quickly distanced themselves from anarchists. They said violent tactics were not helpful. However, many workers thought that agents from the Pinkerton National Detective Agency were involved. This agency was known for secretly joining labor groups and using violence to break strikes.

Legal Proceedings and the Bomber

No one who actually threw the bomb was ever put on trial. Historians like James Joll and Timothy Messer-Kruse suggest that Rudolph Schnaubelt was likely the person who threw the bomb.

Who Threw the Bomb?

Even though people were found guilty of planning the attack, the person who threw the bomb was never officially identified. This made the trials seem less fair to some.

- Rudolph Schnaubelt was a leading suspect. He was at Haymarket when the bomb exploded. He was accused but left Chicago and then the country. A witness said they saw him throw the bomb. Schnaubelt later denied it in letters.

- George Meng was a German anarchist. His granddaughter said her mother told her that Meng was the bomber.

- Some people thought the bomber might have been an agent provocateur. This is someone who tries to cause trouble to make a group look bad. Albert Parsons believed it might have been a police officer or a Pinkerton agent.

- Many thought it was a disgruntled worker. Oscar Neebe, one of the accused, called the bomber a "crank." Governor Altgeld thought it might be a worker with a personal grudge against the police. He blamed police actions for inviting revenge.

Pardons and How History Sees It

Many people, especially those who supported workers' rights, believed the trial was unfair. Famous people like writer William Dean Howells and poet Oscar Wilde spoke out against it.

On June 26, 1893, Illinois Governor John Peter Altgeld pardoned three of the men. He said they were victims of "hysteria, packed juries, and a biased judge." He also noted that the state never found out who threw the bomb. He said there was no proof linking the defendants to the bomber. Altgeld also blamed Chicago for not holding Pinkerton guards responsible for violence against striking workers. His actions made him lose his next election.

Historians have long seen the trial as a "miscarriage of justice." They point out that the judge was biased. Also, all the jurors admitted they were prejudiced against the defendants. However, one historian, Timothy Messer-Kruse, looked at the trial records again. He argued that the trial was fair for its time.

Impact on Workers' Rights and May Day

Workers' unions continued to grow after the Haymarket Affair. In 1886, the Labor Party of Chicago was formed.

People kept pushing for the eight-hour workday. In 1888, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) decided to campaign for it again. They set May 1, 1890, as the day for workers to strike for an eight-hour day.

In 1889, AFL president Samuel Gompers wrote to a meeting of socialists in Paris. He told them about the AFL's plans. He suggested a worldwide fight for a universal eight-hour workday. In response, the international group called for a "great international demonstration." This was to happen on May 1, 1890.

This decision also honored the Haymarket martyrs. These were the workers killed during the strikes on May 1, 1886. Historian Philip Foner said everyone involved knew about the 1886 strikes and the Haymarket tragedy.

The first International Workers Day was a huge success. Newspapers like the New York World reported on it. They wrote about "Parade of Jubilant Workingmen in All the Trade Centers of the Civilized World." The Times of London listed many cities where demonstrations happened. Commemorating May Day became an annual event.

The link between May Day and the Haymarket martyrs is still strong in Mexico. Mary Harris "Mother" Jones wrote about the "day of 'fiestas'" in Mexico. This day marked "the killing of the workers in Chicago for demanding the eight-hour day."

The Haymarket Affair also inspired many activists. Emma Goldman, a famous activist, became an anarchist after reading about the event. She called it "the most decisive influence in my existence." Other people, like Voltairine de Cleyre and "Big Bill" Haywood, were also inspired. Goldman wrote that the Haymarket Affair awakened the social awareness of "hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people."

Burial and Monuments

Lingg, Spies, Fischer, Engel, and Parsons were buried at the German Waldheim Cemetery. This cemetery later joined with Forest Home Cemetery in Forest Park, Illinois. Schwab and Neebe were also buried there later. This reunited the "Martyrs." In 1893, the Haymarket Martyrs' Monument was built at Waldheim. It was designed by sculptor Albert Weinert. Over 100 years later, it was named a National Historic Landmark.

Many activists, like Emma Goldman, chose to be buried near the Haymarket Martyrs' Monument. In 2016, a time capsule about the Haymarket Affair was found in Forest Home Cemetery.

Haymarket Memorials

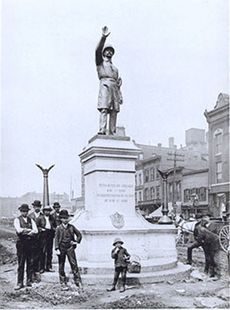

In 1889, a nine-foot bronze statue of a Chicago policeman was put up in Haymarket Square. Sculptor Johannes Gelert created it. Funds were raised privately. The statue was unveiled on May 30, 1889, by the son of Officer Mathias Degan.

On May 4, 1927, a streetcar crashed into the monument. The driver said he was "sick of seeing that policeman." The city fixed the statue in 1928 and moved it to Union Park. Later, the statue was moved again to a platform overlooking the Kennedy Expressway.

The Haymarket statue was damaged with paint in 1968. This happened after a protest against the Vietnam War. On October 6, 1969, the statue was destroyed by a bomb. A group called Weatherman claimed responsibility. The blast broke many windows. The statue was rebuilt in 1970. Weatherman blew it up again on October 6, 1970.

The statue was rebuilt once more. Mayor Richard J. Daley then had a 24-hour police guard protect it. This guard cost a lot of money. In 1972, the statue was moved inside the Central Police Headquarters. In 1976, it went to the Chicago police academy. For decades, the empty, graffitied base of the statue remained in Haymarket Square. It became known as an anarchist landmark. On June 1, 2007, the statue was put back at Chicago Police Headquarters.

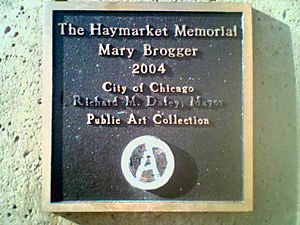

On September 14, 2004, Mayor Daley and union leaders unveiled a new monument. It was created by Chicago artist Mary Brogger. This fifteen-foot sculpture looks like the wagon the labor leaders stood on. It is meant to represent the rally and free speech. This sculpture is planned to be the center of a "Labor Park." The park would have a commemoration wall and other features, but construction has not started yet.

See also

In Spanish: Revuelta de Haymarket para niños

In Spanish: Revuelta de Haymarket para niños

- Bay View Massacre (in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, May 5, 1886)

- First Red Scare of 1919–1920

- International Workers' Day, also known as May Day

- May Day Riots of 1894

- May Day Riots of 1919

- Palmer Raids of 1919

- Sacco and Vanzetti

- Wall Street bombing of 1920

- List of massacres in the United States

- Violent labor disputes in the United States

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- Argentinos Juniores

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |