Emma Goldman facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Emma Goldman

|

|

|---|---|

Goldman, c. 1911

|

|

| Born | June 27, 1869 Kovno, Kovno Governorate, Russian Empire

|

| Died | May 14, 1940 (aged 70) Toronto, Ontario, Canada

|

| School | |

|

Influenced

|

|

| Signature | |

|

|

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a writer and activist born in Russia. She was a key figure in developing anarchist ideas in North America and Europe. This was in the first half of the 1900s.

Born in Kaunas, Lithuania (then part of the Russian Empire), Emma Goldman came from a Jewish family. She moved to the United States in 1885. After a famous event in Chicago called the Haymarket affair, she became interested in anarchism. Goldman became a well-known speaker and writer. She talked about anarchist ideas, women's rights, and other social issues. Thousands of people came to hear her speak. She and her friend Alexander Berkman were both anarchists. They planned an action against a rich businessman named Henry Clay Frick. Frick survived, and Berkman went to prison for 22 years. Goldman herself was put in prison several times. In 1906, she started an anarchist magazine called Mother Earth.

In 1917, Goldman and Berkman were jailed for two years. They were accused of telling people not to sign up for the new military draft. After prison, they were arrested again with many others during the Palmer Raids. They were then sent away to Russia. At first, Goldman supported Russia's October Revolution. This revolution brought the Bolsheviks to power. But she changed her mind after the Kronstadt rebellion. She spoke out against the Soviet Union for stopping people from speaking freely. She left Russia and wrote a book about her experiences in 1923, called My Disillusionment in Russia. While living in England, Canada, and France, she wrote her life story, Living My Life. It was published in two parts in the 1930s. When the Spanish Civil War began, Goldman went to Spain. She wanted to support the anarchist movement there. She passed away in Toronto, Canada, on May 14, 1940, at age 70.

During her life, many people admired Goldman as a free-thinking "rebel woman." Others criticized her for supporting actions that could lead to violence. Her writings and speeches covered many topics. These included prisons, atheism, freedom of speech, militarism, capitalism, marriage, and homosexuality. She didn't fully agree with the first-wave feminism movement. This movement focused on getting women the right to vote. Instead, she found new ways to connect gender issues with anarchism. After being less known for many years, Goldman became a famous figure in the 1970s. This happened when feminist and anarchist thinkers renewed interest in her life.

Contents

- Her Life Story

- Early Years

- Moving and Learning

- Life in America

- New Friends and Ideas

- The Homestead Strike

- Speaking Out and Imprisonment

- McKinley's Assassination and Its Aftermath

- Mother Earth and Berkman's Return

- World War I and Deportation

- Life in Russia

- Later Years in Europe and Canada

- Spanish Civil War Support

- Final Years and Death

- Her Ideas

- Her Impact

- Her Writings

- See also

Her Life Story

Early Years

Emma Goldman was born on June 27, 1869, in Kovno (Kaunas), Lithuania. At that time, Lithuania was part of the Russian Empire. Her family was Orthodox Jewish. Emma's mother, Taube Bienowitch, had two older daughters from a previous marriage. Emma's father, Abraham Goldman, was her mother's second husband. Their marriage was difficult, and money was often tight. Emma was their first child together.

Emma's father was strict and would hit his children. Emma was the most rebellious and often faced his anger. Her mother rarely stepped in to help. Emma had two older half-sisters, Helena and Lena. Helena was kind and brought joy to Emma's childhood. Lena was more distant. Emma also had three younger brothers.

Moving and Learning

When Emma was young, her family moved to a village called Papilė. Her father ran an inn there. One day, she saw a peasant being whipped in the street. This event deeply affected her. It made her dislike violent authority for the rest of her life.

At age seven, Emma moved with her family to Königsberg, a city in Germany at the time. She went to a Realschule there. One teacher would hit students' hands with a ruler, especially Emma. But her German teacher was kind. He lent her books and took her to an opera. Emma loved to learn. She passed an exam to enter a better school, a gymnasium. However, her religion teacher refused to give her a good behavior certificate, so she couldn't go.

The family then moved to Saint Petersburg, the capital of Russia. Her father tried to open several stores, but they all failed. Because they were poor, the children had to work. Emma had many jobs, including one in a corset shop. As a teenager, Emma begged her father to let her go back to school. But he threw her French book into the fire. He said, "Girls do not have to learn much! All a Jewish daughter needs to know is how to prepare gefilte fish, cut noodles fine, and give the man plenty of children."

Emma decided to learn on her own. She studied the political unrest around her. She was especially interested in the Nihilists who had killed Alexander II of Russia. When she read Nikolai Chernyshevsky's novel, What Is to Be Done?, she found a role model. The book inspired her throughout her life. Her father still wanted her to marry young. They argued often, but Emma insisted she would only marry for love.

Life in America

In 1885, Emma's sister Helena planned to move to New York in the United States. Emma wanted to go too, but her father said no. Emma threatened to throw herself into the Neva River if she couldn't go. Her father finally agreed. On December 29, 1885, Emma and Helena arrived in New York City.

They settled in Rochester. Emma's parents and brothers joined them a year later. Emma worked as a seamstress, sewing coats for over ten hours a day. She earned very little money. She asked for a raise, but was denied. She quit and found work at a smaller shop.

At her new job, Emma met Jacob Kershner. They both loved books, dancing, and travel. They also disliked factory work. They married in February 1887. But their relationship became difficult. Emma became more interested in politics, especially after the 1886 Haymarket affair in Chicago. This event led her to the idea of anarchism. Less than a year after marrying, they divorced. Emma's parents were upset with her choices. She left Rochester and moved to New York City.

New Friends and Ideas

In New York City, Goldman met Alexander Berkman, an anarchist. He invited her to a speech by Johann Most. Most was a radical writer who believed in using actions to bring about change. Goldman was impressed by his powerful speaking. Most taught her how to speak in public. She quickly became a strong speaker for "the Cause."

Goldman soon disagreed with Most because she wanted to express her own ideas. She left his group and joined another publication. Meanwhile, she became close friends with Berkman, whom she called Sasha. They became partners and shared a home with friends. They were united by their anarchist beliefs and their commitment to equality.

In 1892, Goldman and Berkman opened an ice cream shop. But soon, they became involved in the Homestead Strike near Pittsburgh.

The Homestead Strike

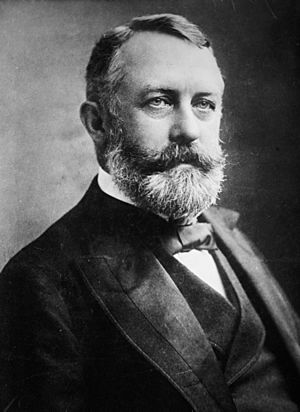

In June 1892, a steel plant in Homestead, Pennsylvania, owned by Andrew Carnegie, had a major conflict. Talks between the company and the workers' union failed. The factory manager was Henry Clay Frick, who strongly opposed the union. The company closed the plant and locked out the workers, who then went on strike. The company hired Pinkerton guards to protect new workers. On July 6, a fight broke out between the guards and armed union workers. Many people were killed on both sides.

Goldman and Berkman decided that an action against Frick would inspire workers to fight against the capitalist system. Berkman decided to carry out the action. Goldman was to explain his reasons afterward. On July 23, Berkman shot Frick three times. He was arrested and sentenced to 22 years in prison. Goldman was very sad during his long absence.

Police thought Goldman was involved. They searched her home but found no proof. The action also failed to inspire the workers. Many people, including other anarchists, criticized Berkman's action. Goldman was furious at these criticisms. She confronted Most publicly for his betrayal. She later regretted her actions.

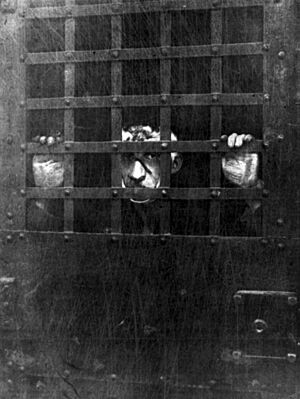

Speaking Out and Imprisonment

In 1893, the United States faced a severe economic crisis. Many people lost their jobs. Goldman began speaking to large crowds in New York City. She encouraged unemployed workers to take action. She told them to demand work and bread. If denied, she urged them to "take bread."

A week later, Goldman was arrested. She was charged with "inciting to riot." A detective offered to drop the charges if she would give information about other radicals. She refused. A reporter from the New York World visited her and wrote a positive article.

Despite the good publicity, the jury found her guilty. The prosecutor questioned her about her anarchist and atheist beliefs. The judge called her "a dangerous woman." She was sentenced to one year in prison. In prison, she studied medicine and read many books. When she was released, a large crowd greeted her. She was soon asked for many interviews and lectures.

To earn money, Goldman continued her medical studies. She traveled to Europe, giving lectures in London, Glasgow, and Edinburgh. She met famous anarchists like Peter Kropotkin. In Vienna, she earned two diplomas in midwifery. She used these skills back in the US. Goldman became the first anarchist speaker to tour across the country. In 1899, she returned to Europe and helped organize an anarchist meeting in Paris.

McKinley's Assassination and Its Aftermath

On September 6, 1901, Leon Czolgosz shot US President William McKinley. McKinley died eight days later. Czolgosz claimed he was an anarchist and was inspired by Goldman's speeches. Authorities used this to accuse Goldman of planning the assassination. She was arrested along with several other anarchists.

Czolgosz had tried to befriend Goldman and her group earlier. But they thought he was a spy and kept their distance. Czolgosz repeatedly said Goldman was not involved. Police held her for two weeks and questioned her intensely. They finally realized she had no real contact with him. She was released. Goldman refused to condemn Czolgosz's actions. She defended him as a "supersensitive being." Many friends, including Berkman, urged her to stop supporting him. After these events, socialism gained more support than anarchism in the US. President Theodore Roosevelt promised to crack down on anarchists and their supporters.

Mother Earth and Berkman's Return

After Czolgosz was executed, Goldman withdrew from public life for a while. She lived in New York City from 1903 to 1913. She was sad and felt alone. She worked as a private nurse. The US Congress passed the Anarchist Exclusion Act in 1903. This law allowed the government to deport non-citizens who were anarchists. This law brought Goldman back into activism. Many people opposed the law, saying it violated freedom of speech.

In 1906, Goldman decided to start a new publication. She wanted it to be "a place of expression for the young idealists in arts and letters." This was Mother Earth. It was run by radical activists. The magazine published original works and writings from famous thinkers like Peter Kropotkin and Friedrich Nietzsche. Goldman often wrote about anarchism, politics, labor issues, atheism, and feminism. She was the first editor.

On May 18, 1906, Alexander Berkman was released from prison. Goldman met him at the train station. She was shocked by how thin and pale he looked. He struggled to adjust to life outside. He even thought about taking his own life. But when he heard Goldman had been arrested, he felt renewed. He worked to get her and others released.

Berkman took over editing Mother Earth in 1907. Goldman traveled the country to raise money for the magazine. Their relationship became difficult. Goldman believed it was because of his time in prison. Later that year, she went to the International Anarchist Congress of Amsterdam. She continued to speak to large audiences in the US.

World War I and Deportation

In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson was re-elected. But soon after, he announced that the US would enter World War I. Congress passed the Selective Service Act of 1917. This law required all men aged 21–30 to sign up for the military draft. Goldman saw this as an act of militarism driven by capitalism. She declared in Mother Earth that she would resist the draft and oppose US involvement in the war.

She and Berkman started the No Conscription League in New York. They said, "We oppose conscription because we are internationalists, antimilitarists, and opposed to all wars waged by capitalistic governments." The group became a leader in anti-draft efforts. They distributed pamphlets and writings. Many political groups did not support their efforts.

On June 15, 1917, Goldman and Berkman were arrested. Authorities seized many anarchist writings from their offices. They were charged with trying to get people not to register for the draft. This was under the new Espionage Act. They were held on high bail.

The jury found them guilty. The judge gave them the maximum sentence: two years in prison, a $10,000 fine each, and possible deportation after release. Goldman was sent to prison in Missouri. There, she met socialist Kate Richards O'Hare. They worked together to improve conditions for prisoners. Goldman also became friends with Gabriella Segata Antolini, another anarchist. The three women were known as "The Trinity." Goldman was released on September 27, 1919.

Goldman and Berkman were released during the Red Scare of 1919–20. This was a time of great fear about communism and radical revolution in the US. The government wanted to deport any non-citizens who supported anarchy or revolution. J. Edgar Hoover, a government official, called Goldman and Berkman "two of the most dangerous anarchists in this country."

At her deportation hearing, Goldman refused to answer questions. She argued that her American citizenship meant she could not be deported. However, a government official ruled that her husband's earlier loss of citizenship also took away hers. Goldman decided not to fight the ruling.

Goldman and Berkman were among 249 people sent away from the US. Most of these people had only loose ties to radical groups. They were deported en masse on a ship nicknamed the "Soviet Ark." The ship arrived in Finland on January 17, 1920. From there, they were taken to the Russian border.

Life in Russia

At first, Goldman saw the Bolshevik revolution in Russia as a positive step. She believed it would bring human freedom and economic well-being. But as she traveled, her hopes faded. She found repression, poor management, and corruption. People who questioned the government were called "counter-revolutionaries." Workers faced harsh conditions. She and Berkman met with Vladimir Lenin, who told them that limiting free speech was necessary during a revolution. Berkman initially tried to understand the government's actions, but eventually he agreed with Goldman that the Soviet state was too controlling.

In March 1921, workers in Petrograd went on strike. They demanded better food and more union freedom. Goldman and Berkman felt they had to support the strikers. The unrest spread to the town of Kronstadt. The government responded with military force. In the Kronstadt rebellion, many striking soldiers and sailors were killed or arrested. After these events, Goldman and Berkman decided they could not stay in Russia. They left in December 1921 and went to Latvia.

They then moved to Berlin for several years. During this time, Goldman wrote articles about her experiences in Russia for a newspaper. These were later published as books: My Disillusionment in Russia (1923) and My Further Disillusionment in Russia (1924).

Later Years in Europe and Canada

Goldman found it hard to fit in with the leftist groups in Berlin. Communists disliked her criticism of Soviet rule. Liberals thought she was too radical. In 1924, Goldman moved to London. She spoke about her disappointment with the Soviet government, which surprised many people.

In 1925, to avoid being deported again, Goldman married James Colton, a Scottish anarchist she knew. This gave her British citizenship, allowing her to travel to France and Canada. Life in London was stressful for her. She wrote to Berkman that she felt "lonely and heartsick."

In 1927, Goldman traveled to Canada. She heard about the upcoming executions of Italian anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti in Boston. She was very upset by the unfairness of their case.

In 1928, she began writing her autobiography. A group of American admirers, including writer H. L. Mencken and art collector Peggy Guggenheim, raised money for her. She rented a cottage in Saint-Tropez, France, and spent two years writing her life story. Berkman gave her critical feedback, which she used. Her book, Living My Life, was published in two volumes. Sales were slow due to the Great Depression. However, critics generally liked it.

In 1933, Goldman was allowed to lecture in the United States again. But she could only speak about drama and her autobiography, not current politics. She returned to New York in 1934. The press generally welcomed her, except for Communist publications. Her visa expired, and her request to visit the US again was denied. She stayed in Canada and wrote articles.

In 1936, Berkman had prostate operations. He died later that year. Goldman was deeply saddened by his death.

Spanish Civil War Support

In July 1936, the Spanish Civil War began. At the same time, Spanish anarchists started an anarchist revolution. Goldman was invited to Barcelona. She felt a new sense of purpose after Berkman's death. She was welcomed by the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) and Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI) groups. For the first time, she lived in a community run by anarchists. She said she had never met with such "warm hospitality, comradeship and solidarity." After visiting various communities, she told workers, "Your revolution will destroy forever [the idea] that anarchism stands for chaos." She began editing the CNT-FAI Information Bulletin in English.

Goldman became worried when the CNT-FAI joined the government in 1937. This went against a core anarchist idea of not being part of state structures. She was also concerned about their compromises with Communist forces. She wrote that working with Communists was "a denial of our comrades in Stalin's concentration camps." The Soviet Union refused to send weapons to the anarchists. Misinformation campaigns were spread against anarchists. Goldman's faith in the movement remained strong. She returned to London as an official representative of the CNT-FAI.

Goldman gave lectures and interviews, strongly supporting the Spanish anarchists. She wrote for Spain and the World, a newspaper about the civil war. In May 1937, Communist-led forces attacked anarchist areas. Newspapers in England often accepted the official story from the Spanish government. British journalist George Orwell, who was there, wrote that the news reports were full of lies.

Goldman returned to Spain in September, but the situation was dire. Anarchists and other radicals around the world did not support their cause. The Nationalist forces won the war in Spain just before she returned to London. Frustrated by England's strict atmosphere, she returned to Canada in 1939. Her work for the anarchist cause in Spain was remembered. On her seventieth birthday, a former leader of the CNT-FAI praised her as "our spiritual mother." She called it "the most beautiful tribute I have ever received."

Final Years and Death

As World War II approached, Goldman repeated her opposition to wars fought by governments. She wrote that she would not support a war against leaders like Adolf Hitler or Joseph Stalin. She felt that Britain and France had missed their chance to stop fascism. She believed the coming war would only bring "a new form of madness in the world."

On February 17, 1940, Goldman had a stroke. She became paralyzed on her right side and could not speak. A friend said, "Just to think that here was Emma, the greatest orator in America, unable to utter one word." She slowly improved for three months. She had another stroke on May 8 and died six days later in Toronto, at age 70.

The US government allowed her body to be brought back to the United States. She was buried in German Waldheim Cemetery in Forest Park, Illinois. This cemetery is near the graves of those executed after the Haymarket affair. Her grave marker has a carving by sculptor Jo Davidson. It includes the quote: "Liberty will not descend to a people, a people must raise themselves to liberty."

Her Ideas

Goldman spoke and wrote a lot about many different topics. She did not like strict, unchanging ways of thinking. She was an important contributor to modern political ideas.

She was influenced by many thinkers. These included Mikhail Bakunin, Henry David Thoreau, Peter Kropotkin, and Mary Wollstonecraft. Another important influence was Friedrich Nietzsche. Goldman wrote that Nietzsche was a "poet, a rebel, and innovator." She believed his idea of aristocracy was about spirit, not birth or money. In this way, she saw him as an anarchist.

Anarchism

Anarchism was central to Goldman's view of the world. Today, she is seen as one of the most important figures in anarchist history. She became interested in anarchism after the persecution of anarchists following the 1886 Haymarket affair. She wrote and spoke regularly about it.

Goldman believed that anarchism was deeply personal. She felt that anarchists should live their beliefs every day. She wrote, "I don't care if a man's theory for tomorrow is correct. I care if his spirit of today is correct." She saw anarchism and free association as natural responses to government control and capitalism. She believed these new ways of life would replace the old ones, not by preaching or voting, but by living them.

Capitalism and Work

Goldman believed that capitalism was not compatible with human freedom. She wrote that property only cares about "its own gluttonous appetite for greater wealth." This is because wealth means power: "the power to subdue, to crush, to exploit, the power to enslave, to outrage, to degrade." She also argued that capitalism made workers less human. It turned them into "a mere particle of a machine."

Goldman was originally against anything less than a complete revolution. But she was challenged by an elderly worker during one of her talks.

The Role of Government

Goldman saw the government as a tool of control. Because of this, she believed that voting was useless or even dangerous. She wrote that voting gave people the false idea that they were participating. It hid the real ways decisions were made. Instead, Goldman supported direct actions like strikes and protests. She believed these were ways to fight against authority. She kept her anti-voting stance even when many anarchists in Spain voted for a liberal government in the 1930s. Goldman thought that any power anarchists had should be used for strikes across the country. She also disagreed with the movement for women's suffrage, which wanted women to have the right to vote. She believed that women's involvement alone would not make the government more fair. She was also critical of Zionism, seeing it as another failed attempt at state control.

Goldman also strongly criticized the prison system. She spoke out against how prisoners were treated and the social reasons for crime.

She was a strong opponent of war, especially the military draft. She saw the draft as one of the worst ways the government forced people to do things. She helped start the No-Conscription League. For this, she was arrested and imprisoned in 1917, then deported in 1919.

Goldman was often watched, arrested, and imprisoned. This was for her speeches and organizing activities supporting workers and strikes. It was also for her opposition to World War I. Because of this, she became active in the early 1900s free speech movement. She saw freedom of expression as vital for social change. Her strong fight for her beliefs, despite arrests, inspired Roger Nash Baldwin, who helped start the American Civil Liberties Union.

Atheism

Goldman was a strong atheist. She believed that religion was another way to control and dominate people.

In her writings and speeches, Goldman often criticized religious groups. She attacked their moralistic views and their attempts to control human behavior. She blamed Christianity for keeping people in a "slave society." She argued that it told people how to act on Earth and offered a false promise of a good future in heaven.

Her Impact

Goldman was very famous during her lifetime. She was even called "the most dangerous woman in America." After she died, her fame faded for a while. Scholars saw her as a great speaker and activist. But they didn't see her as a deep thinker like Peter Kropotkin.

In the 1970s, interest in Goldman's life grew again. Her autobiography, Living My Life, was reissued. A collection of her writings, Red Emma Speaks, was published. These books brought her ideas to more people. She became especially important to the women's movement of the late 20th century. A famous quote, "If I can't dance, I don't want to be in your revolution," became linked to her. While she probably didn't say it exactly that way, it captures her spirit. This saying has appeared on many items like T-shirts and posters.

The renewed interest in Goldman also came with a new anarchist movement in the late 1960s. Scholars began to look at her ideas more closely. They recognized her important contributions to anarchist thought. For example, her belief in the importance of aesthetics (beauty and art) can be seen in how anarchism and art later influenced each other. Goldman is now also recognized for greatly influencing activism on reproductive rights and freedom of expression.

Goldman has been shown in many stories and plays. She was played by Maureen Stapleton in the 1981 film Reds, for which Stapleton won an Academy Award. Goldman has also been a character in Broadway musicals like Ragtime. Plays about her life include Howard Zinn's Emma and Martin Duberman's Mother Earth.

Several organizations are named in her honor. The Emma Goldman Clinic, a women's health center, chose her name to recognize her "challenging spirit." Red Emma's Bookstore Coffeehouse in Baltimore adopted her name. They believe in the ideas she fought for: free speech, equality, and the right to organize.

Her Writings

Goldman wrote a lot. She wrote many pamphlets and articles on various topics. She also wrote six books, including her life story, Living My Life.

See also

In Spanish: Emma Goldman para niños

In Spanish: Emma Goldman para niños

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |