H. L. Mencken facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

H. L. Mencken

|

|

|---|---|

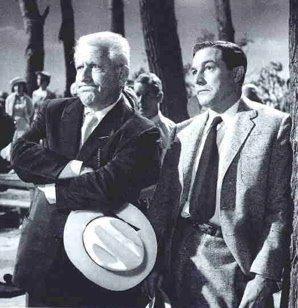

Mencken in 1928

|

|

| Born |

Henry Louis Mencken

September 12, 1880 |

| Died | January 29, 1956 (aged 75) Baltimore, Maryland, U.S.

|

| Occupation | |

|

Notable credit(s)

|

The Baltimore Sun |

| Spouse(s) |

Sara Haardt

(m. 1930; died 1935) |

| Parent(s) | August Mencken Sr. |

| Relatives | August Mencken Jr. (brother) |

Henry Louis Mencken (born September 12, 1880 – died January 29, 1956) was an American journalist and writer. He was known for his essays, satire, and comments on American culture and language. He often wrote about society, books, music, and important people.

Mencken's home in Union Square, Baltimore, is now a city museum called the H. L. Mencken House. His writings and papers are kept in libraries, with the biggest collection at the Enoch Pratt Free Library in Baltimore.

Contents

H. L. Mencken's Early Life and Education

Henry Louis Mencken was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on September 12, 1880. His father, August Mencken Sr., owned a cigar factory. Henry's family had German roots, and he spoke German when he was a child. When he was three, his family moved to a house on Hollins Street, where he lived for most of his life.

In his book Happy Days, Mencken described his childhood as "placid, secure, uneventful and happy."

When he was nine, he read Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn. He later called it "the most stupendous event in my life." This book made him want to become a writer. He read many books, including works by Shakespeare and Rudyard Kipling. Mencken also liked science and had a chemistry lab at home.

He went to Professor Knapp's School and later graduated from the Baltimore Polytechnic Institute in 1896. He was 15 years old and was the top student in his class.

After school, he worked in his father's cigar factory for three years. He didn't like the sales part of the job. In 1898, he took a writing class by mail. This was all the formal training he had for journalism. After his father passed away, Mencken was free to start his writing career. In 1899, he began working as a part-time reporter for the Morning Herald newspaper. Soon after, he became a full-time reporter.

Mencken's Journalism Career

Mencken worked as a reporter for the Herald for six years. In 1906, he moved to The Baltimore Sun newspaper. He wrote for The Sun and its related papers until 1948, when he had a stroke and stopped writing.

At The Sun, Mencken became famous for his editorials and opinion pieces. He also wrote short stories, a novel, and poetry. In 1908, he became a literary critic for The Smart Set magazine. In 1924, he and George Jean Nathan started their own magazine, The American Mercury. This magazine became very popular and important on college campuses across America. Mencken stopped being its editor in 1933.

H. L. Mencken's Personal Life

Marriage to Sara Haardt

In 1930, Mencken married Sara Haardt. She was a professor of English and a writer, 18 years younger than him. They met in 1923, and their courtship lasted seven years. Many people were surprised by their marriage because Mencken often joked about marriage. He once called it "the end of hope."

Sara Haardt was not in good health during their marriage. She suffered from tuberculosis and died in 1935 from meningitis. Mencken was very sad after her death. He had always supported her writing. After she passed away, he helped publish a collection of her short stories called Southern Album.

Later Years and Challenges

During the Great Depression, Mencken did not support President Franklin D. Roosevelt's "New Deal" programs. He also had strong doubts about the U.S. joining World War II. These views made him less popular. He stopped writing for The Baltimore Sun for several years. During this time, he focused on writing his memoirs and other projects.

In 1948, Mencken briefly returned to cover the presidential election. His later writings were often funny and told stories from his past. These essays were published in books like Happy Days, Newspaper Days, and Heathen Days.

Last Years and Death

On November 23, 1948, Mencken had a stroke. This made it very hard for him to read, write, or speak. He could still understand things and talk with friends, but with difficulty. He enjoyed listening to classical music. In his last year, his friend William Manchester read to him every day.

Mencken passed away in his sleep on January 29, 1956. He was buried in Baltimore's Loudon Park Cemetery. He had once written a funny epitaph for himself:

If, after I depart this vale, you ever remember me and have thought to please my ghost, forgive some sinner and wink your eye at some homely girl.

A small, private service was held, as Mencken had wished. He cared a lot about his legacy. He kept many of his papers, letters, and writings. After his death, these materials were made available to scholars. They include thousands of letters he sent and received.

Mencken's Friends and Influences

As an editor, Mencken became good friends with many famous writers of his time. These included Theodore Dreiser, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Sinclair Lewis. He also helped many young reporters, like Alistair Cooke. Mencken supported artists whose work he admired. For example, he believed that books like Caught Short! helped America more during the Great Depression than government actions. He also mentored writer John Fante.

Mencken also wrote many works using different fake names, such as Owen Hatteras. He even ghostwrote parts of a book about baby care for a doctor.

Mencken admired the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. He was the first writer to deeply analyze Nietzsche's ideas in English. He also liked Joseph Conrad. Mencken's humor and satire were influenced by writers like Ambrose Bierce and Mark Twain. For Mencken, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was the best American book ever written.

Mencken's Ideas and Beliefs

Views on People and Society

Mencken believed that within any group of people, there are always a few who are naturally superior. He thought these "superior" individuals were often misunderstood or looked down upon by others. He believed they stood out because of their strong will and achievements, not because of their background.

Some historians, like Larry S. Gibson, say that Mencken's ideas about race changed over time. They suggest that his own experiences of being treated as an outsider because of his German background during World War I influenced his views.

Science and Mathematics

Mencken supported Charles Darwin's ideas about evolution. However, he often spoke negatively about many famous physicists and did not think much of pure mathematics. He even made fun of Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity.

Places Remembering H. L. Mencken

Mencken's Home in Baltimore

Mencken's home at 1524 Hollins Street in Baltimore's Union Square neighborhood was where he lived for 67 years. After his younger brother August died in 1967, the house was given to the University of Maryland, Baltimore. In 1983, the City of Baltimore took over the property. The H. L. Mencken House became part of the City Life Museums. It has been closed to the public since 1997, but it sometimes opens for special events and group visits.

Mencken's Papers and Collections

After World War II, Mencken decided to give his books and papers to Baltimore's Enoch Pratt Free Library. When he died, the library received most of his large collection. This collection includes his writings, newspaper articles, books, family items, and many letters. The "H. L. Mencken Room and Collection" was opened at the library in 1956. A new Mencken Room opened in 2003.

Other important collections of Mencken's work are at Dartmouth College, Harvard University, Princeton University, Johns Hopkins University, and Yale University. In 2007, Johns Hopkins received nearly 6,000 books, photos, and letters by and about Mencken.

The Sara Haardt Mencken collection at Goucher College has letters between Sara and Mencken. Some of Mencken's many letters are also at the New York Public Library.

H. L. Mencken's Books

- George Bernard Shaw: His Plays (1905)

- The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche (1907)

- The Gist of Nietzsche (1910)

- What You Ought to Know about your Baby (1910)

- Men versus the Man (1910)

- Europe After 8:15 (1914)

- A Book of Burlesques (1916)

- A Little Book in C Major (1916)

- A Book of Prefaces (1917)

- In Defense of Women (1918)

- D***n! A Book of Calumny (1918)

- The American Language (1919)

- Prejudices (1919–27)

- First Series (1919)

- Second Series (1920)

- Third Series (1922)

- Fourth Series (1924)

- Fifth Series (1926)

- Sixth Series (1927)

- Selected Prejudices (1927)

- Heliogabalus (A Buffoonery in Three Acts) (1920)

- The American Credo (1920)

- Notes on Democracy (1926)

- Menckeneana: A Schimpflexikon (1928) – Editor

- Treatise on the Gods (1930)

- Making a President (1932)

- Treatise on Right and Wrong (1934)

- Happy Days, 1880–1892 (1940)

- Newspaper Days, 1899–1906 (1941)

- A New Dictionary of Quotations (1942)

- Heathen Days, 1890–1936 (1943)

- Christmas Story (1944)

- The American Language, Supplement I (1945)

- The American Language, Supplement II (1948)

- A Mencken Chrestomathy (1949)

|

See also

In Spanish: H. L. Mencken para niños

In Spanish: H. L. Mencken para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |