F. Scott Fitzgerald facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

F. Scott Fitzgerald

|

|

|---|---|

Fitzgerald in 1929

|

|

| Born | Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald September 24, 1896 Saint Paul, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Died | December 21, 1940 (aged 44) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Saint Mary's Cemetery Rockville, Maryland, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Princeton University (no degree) |

| Years active | 1920–1940 |

| Notable works | The Beautiful and Damned, The Great Gatsby, All the Sad Young Men, Tender Is the Night |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Frances Scott Fitzgerald |

| Signature | |

|

|

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (born September 24, 1896 – died December 21, 1940) was an American writer. He wrote novels, essays, and short stories. He is most famous for his books about the exciting and sometimes wild 1920s, an era he called the "Jazz Age". He even helped make this term popular in his book Tales of the Jazz Age.

During his life, Fitzgerald published four novels, four collections of stories, and 164 short stories. He was very popular and earned a lot of money in the 1920s. However, critics only truly praised his work after he died. Today, many people believe he was one of the greatest American writers of the 20th century.

Contents

- His Life Story

- Growing Up and Early Years

- Princeton University and Ginevra King

- Army Service and Zelda Sayre

- Challenges and Writing Success

- New York City and the Jazz Age

- Long Island and His Second Novel

- Europe and The Great Gatsby

- Hemingway and the Lost Generation

- Time in Hollywood and Lois Moran

- Zelda's Health and His Last Novel

- The Great Depression and Challenges

- Return to Hollywood

- Final Year and Death

- Fame After Death

- His Influence and Legacy

- Famous Works

- Images for kids

- See also

His Life Story

Growing Up and Early Years

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald was born on September 24, 1896, in Saint Paul, Minnesota. His family was middle-class and Catholic. He was named after a distant cousin, Francis Scott Key, who wrote the words to the American national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner".

His mother was Mary "Molly" McQuillan Fitzgerald. Her father was a wealthy grocer. His father, Edward Fitzgerald, came from Irish and English families. He moved to Minnesota after the American Civil War to start a business.

A year after Fitzgerald was born, his father's business failed. The family moved to Buffalo, New York, where his father became a salesman for Procter & Gamble. Fitzgerald spent most of his early childhood in Buffalo. He went to two Catholic schools there. As a boy, his friends said he was very smart and loved literature.

In 1908, his father lost his job, and the family moved back to Saint Paul. Even though his father had no money, his mother's inheritance helped them keep their middle-class lifestyle. Fitzgerald went to St. Paul Academy from 1908 to 1911. When he was 13, his first story was published in the school newspaper. In 1911, his parents sent him to the Newman School, a Catholic prep school in Hackensack, New Jersey. There, a teacher named Father Sigourney Fay saw his talent and encouraged him to write.

Princeton University and Ginevra King

After finishing prep school in 1913, Fitzgerald went to Princeton University. He was one of the few Catholic students there. He became good friends with classmates Edmund Wilson and John Peale Bishop, who later helped his writing career. Fitzgerald wanted to be a successful writer. He wrote stories and poems for school clubs and magazines like the Princeton Tiger.

During his second year, 18-year-old Fitzgerald met 16-year-old Ginevra King during Christmas break. She was a young woman from a wealthy Chicago family. They started a romantic relationship that lasted several years. Ginevra became a model for characters in his books, like Isabelle Borgé in This Side of Paradise and Daisy Buchanan in The Great Gatsby.

Fitzgerald tried to keep their relationship going, even traveling to visit her family's estate. But Ginevra's wealthy family did not approve of him because he was not as rich as her other boyfriends. Her father reportedly told Fitzgerald that "poor boys shouldn't think of marrying rich girls."

After Ginevra rejected him, Fitzgerald joined the United States Army during World War I. He became a second lieutenant. He hoped to die in battle on the Western front. While waiting to be sent overseas, he was stationed at Fort Leavenworth. His commander was Captain Dwight D. Eisenhower, who later became a famous general and U.S. President. Fitzgerald did not like Eisenhower's authority. Hoping to publish a novel before he might die, Fitzgerald quickly wrote a book called The Romantic Egotist. A publisher, Scribner's, turned it down. But the editor, Max Perkins, liked Fitzgerald's writing and told him to try again after making changes.

Army Service and Zelda Sayre

In June 1918, Fitzgerald was stationed at Camp Sheridan near Montgomery, Alabama. Trying to get over Ginevra, he started dating other young women. At a country club, he met Zelda Sayre. She was 17, a "Southern belle" from a wealthy family. Zelda was very popular among Montgomery's high society. They soon started a romance. Fitzgerald still wrote to Ginevra, hoping to get back together, but it was too late. Three days after Ginevra married a rich businessman, Fitzgerald told Zelda he loved her in September 1918.

In November 1918, Fitzgerald was moved to Camp Mills, New York. While he was there, World War I ended with an armistice.

He was discharged from the army on February 14, 1919. He moved to New York City, looking for a job at newspapers but without success. He then wrote advertisements to support himself while trying to become a fiction writer. Fitzgerald wrote to Zelda often. By March 1920, he had sent her his mother's ring, and they were officially engaged. Some of Fitzgerald's friends did not think Zelda was right for him. Zelda's family was also worried about Scott because he was Catholic and did not have much money.

Fitzgerald worked for an advertising agency and lived in a small room in New York City. He wanted a successful writing career. He wrote several short stories in his free time. He was rejected over 120 times and only sold one story, "Babes in the Woods," for a small amount of money ($30).

Challenges and Writing Success

Fitzgerald's dreams of a great career in New York City were not working out. He could not convince Zelda that he could support her, so she broke off their engagement in June 1919. This made him very sad, especially after Ginevra had also rejected him. While New York City was starting its "Jazz Age," Fitzgerald felt lost. He hated his advertising job, his stories weren't selling, and he had no money for new clothes.

In July, Fitzgerald quit his advertising job and went back to St. Paul. Feeling like a failure, he lived on the top floor of his parents' home at 599 Summit Avenue. He decided to try one last time to become a novelist. He worked day and night to revise The Romantic Egotist into This Side of Paradise. This book was about his time at Princeton and his relationships with Ginevra, Zelda, and others.

While revising his novel, Fitzgerald took a job repairing car roofs. One evening in the fall of 1919, after a long day at work, he received a telegram from Scribner's. It said his revised book had been accepted for publication! Fitzgerald was so happy that he ran through the streets of St. Paul, stopping cars to share the news.

Fitzgerald's first novel came out on March 26, 1920, and was an instant success. This Side of Paradise sold about 40,000 copies in its first year. Within months, it became a cultural sensation in the United States, and F. Scott Fitzgerald became a famous name. Critics praised the book. Magazines now accepted his stories that had been rejected before. The Saturday Evening Post published his story "Bernice Bobs Her Hair" with his name on the cover in May 1920.

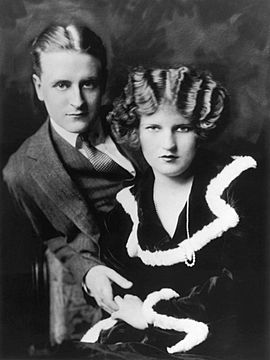

Fitzgerald's new fame meant he could earn much more money for his short stories. Zelda then agreed to marry him again, as he could now pay for the lifestyle she was used to. Despite their doubts, they married in a simple ceremony on April 3, 1920, at St. Patrick's Cathedral, New York. Fitzgerald later said that neither he nor Zelda loved each other at the time of their wedding. The early years of their marriage were more like a friendship.

New York City and the Jazz Age

Living in luxury at the Biltmore Hotel in New York City, the newlyweds became national celebrities. They were known for their wild behavior as much as for Fitzgerald's successful novel.

Fitzgerald was one of the most famous writers during the Jazz Age. Many people wanted to meet him. He became friends with writers like Ring Lardner and Rebecca West. He also met critics George Jean Nathan and H. L. Mencken, who were important editors of The Smart Set magazine. At the peak of his success, Fitzgerald remembered crying in a taxi one day. He realized he would never be as happy again.

Fitzgerald's happiness reflected the excitement of the Jazz Age. He helped make the term popular in his essays and stories. He described the era as moving "along under its own power, served by great filling stations full of money." For Fitzgerald, this time was about people becoming less traditional and more focused on having fun.

In the winter of 1921, Zelda became pregnant while Fitzgerald worked on his second novel, The Beautiful and Damned. The couple traveled to his home in St. Paul, Minnesota, for the birth. On October 26, 1921, Zelda gave birth to their daughter and only child, Frances Scott "Scottie" Fitzgerald.

Long Island and His Second Novel

After his daughter was born, Fitzgerald continued writing The Beautiful and Damned. The novel is about a young artist and his wife who become poor and unhappy from too much partying in New York City. Fitzgerald based the character of Anthony Patch on himself and Gloria Patch on Zelda. Metropolitan Magazine published parts of the book in late 1921. Scribner's published the full book in March 1922. It sold well, with about 50,000 copies sold. That year, Fitzgerald also released a collection of eleven stories called Tales of the Jazz Age.

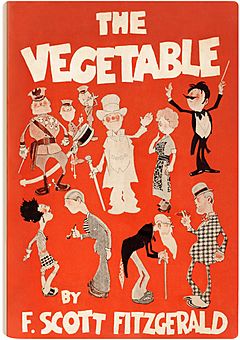

In October 1922, Fitzgerald and Zelda moved to Great Neck, Long Island. They wanted to be close to Broadway, where Fitzgerald hoped his play, The Vegetable, would be a hit. However, the play's first night in November 1923 was a disaster. The audience was bored and left during the second act. Fitzgerald was very upset. Because the play failed, Fitzgerald was in debt. He wrote short stories to earn money. He felt most of his stories were not very good, except for "Winter Dreams", which he said was his first idea for The Great Gatsby. When not writing, Fitzgerald and his wife continued to attend parties on Long Island.

Fitzgerald enjoyed the Long Island social scene but did not always approve of the lavish parties. He often felt disappointed by the wealthy people he met. While he wanted to be like the rich, he also felt a strong dislike for their privileged lifestyle. One of Fitzgerald's wealthy neighbors on Long Island was Max Gerlach. Gerlach was a former soldier who became a successful bootlegger (someone who illegally sells alcohol). He lived like a millionaire, threw big parties, and often used the phrase "old sport." He also created myths about himself. These details inspired Fitzgerald to create his next great work, The Great Gatsby.

Europe and The Great Gatsby

In May 1924, Fitzgerald and his family moved to Europe. He continued writing his third novel, which would become his magnum opus (greatest work), The Great Gatsby. Fitzgerald had been planning this novel since 1923. He told his publisher, Maxwell Perkins, that he wanted to create a beautiful and complex work of art. He had already written a lot for the novel but threw most of it away because it was not right. The book was first called Trimalchio. It was about a new rich man who tries to get wealthy to win the woman he loves. Fitzgerald used his experiences on Long Island and his feelings for Ginevra King as inspiration. He later explained, "The whole idea of Gatsby is the unfairness of a poor young man not being able to marry a girl with money. This theme comes up again and again because I lived it."

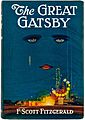

After some marital difficulties, the Fitzgeralds moved to Rome. Fitzgerald revised the Gatsby manuscript during the winter and sent the final version in February 1925. He turned down an offer of $10,000 for the rights to publish parts of the book in a magazine, because it would delay the book's release. When The Great Gatsby was published on April 10, 1925, famous writers like Willa Cather, T. S. Eliot, and Edith Wharton praised it. Most critics also gave it good reviews. However, Gatsby did not sell as well as his previous books, This Side of Paradise (1920) and The Beautiful and Damned (1922). By the end of the year, fewer than 23,000 copies had sold. For the rest of his life, The Great Gatsby had low sales. It took many decades for the novel to become as famous and loved as it is today.

Hemingway and the Lost Generation

After spending the winter in Italy, the Fitzgeralds returned to France. They lived between Paris and the French Riviera until 1926. During this time, Fitzgerald became friends with writer Gertrude Stein, bookseller Sylvia Beach, novelist James Joyce, and poet Ezra Pound. These writers were part of the American community living in Paris, some of whom were called the Lost Generation. The most notable among them was a then-unknown writer named Ernest Hemingway. Fitzgerald met Hemingway in May 1925 and greatly admired him. Hemingway later said that Fitzgerald was his most loyal friend during this early period.

Hemingway, however, did not like Zelda. He claimed that Zelda wanted her husband to write short stories that paid well, instead of novels. This was so she could keep her lifestyle. Zelda later said, "I always felt a story in the [Saturday Evening] Post was tops. But Scott couldn't stand to write them." To earn more money, Fitzgerald often wrote stories for magazines like The Saturday Evening Post and Esquire. He would first write his stories in a true-to-life way. Then, he would rewrite them to add plot twists that made them more appealing to magazines.

In December 1926, after two difficult years in Europe that strained their marriage, the Fitzgeralds returned to America.

Time in Hollywood and Lois Moran

In 1926, film producer John W. Considine Jr. invited Fitzgerald to Hollywood. He wanted Fitzgerald to write a comedy about a flapper (a fashionable young woman of the 1920s) for United Artists. Fitzgerald agreed and moved into a studio bungalow with Zelda in January 1927.

At a party, Fitzgerald met 17-year-old Lois Moran. She was a young actress famous for her role in Stella Dallas (1925). Moran and Fitzgerald talked about books and ideas for hours. Moran saw Fitzgerald as a sophisticated and talented writer. She became a source of inspiration for him. He wrote her into a short story called "Magnetism." Fitzgerald later changed the character Rosemary Hoyt in Tender is the Night to be like Moran.

Fitzgerald's friendship with Moran made his marriage with Zelda even harder. After just two months in Hollywood, the unhappy couple left for Delaware in March 1927.

Zelda's Health and His Last Novel

The Fitzgeralds rented a mansion called "Ellerslie" near Wilmington, Delaware, until 1929. Fitzgerald tried to work on his fourth novel, but he struggled to make progress. In spring 1929, the couple returned to Europe. That winter, Zelda's behavior became more difficult. Doctors diagnosed Zelda with a mental illness in June 1930. The couple traveled to Switzerland, where she received treatment. They returned to America in September 1931. In February 1932, she was hospitalized at the Phipps Clinic at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland.

In April 1932, when Zelda was allowed to travel with her husband, Fitzgerald took her to lunch with critic H. L. Mencken. Mencken noted in his diary that Zelda "went insane in Paris a year or so ago, and is still plainly more or less off her base." She showed signs of mental distress during the lunch. A year later, Mencken met Zelda again and described her mental illness as clear to anyone who saw her. He felt sad that Fitzgerald had to write magazine stories to pay for Zelda's treatment, instead of focusing on novels.

During this time, Fitzgerald rented a home called "La Paix" near Towson, Maryland. He worked on his next novel, using his recent experiences. The story was about a promising young American man who marries a woman with mental health struggles. Their marriage gets worse while they are in Europe. While Fitzgerald worked on his novel, Zelda wrote her own story about these same events, called Save Me the Waltz (1932). Fitzgerald was annoyed, feeling she had taken his plot idea. He called Zelda a "plagiarist" and a "third-rate writer." Despite his anger, he only asked for a few changes to her book. He convinced Perkins to publish Zelda's novel. Scribner's published Zelda's novel in October 1932, but it did not sell well or receive good reviews.

Fitzgerald's own novel, Tender Is the Night, came out in April 1934. It received mixed reviews. Many critics felt its structure was confusing and that Fitzgerald had not met their expectations. Some, like Hemingway, argued that this criticism came from not reading the book carefully enough. They also thought it was because people in the Great Depression era reacted negatively to Fitzgerald, who was a symbol of the Jazz Age's excesses. The novel did not sell well at first, but like The Great Gatsby, its reputation has grown significantly over time.

The Great Depression and Challenges

As his popularity decreased, Fitzgerald began to struggle with money. By 1936, his book earnings were very low. The cost of his expensive lifestyle and Zelda's medical bills quickly put him in debt. He relied on loans from his agent, Harold Ober, and his publisher, Perkins. When Ober stopped lending him money, Fitzgerald, feeling ashamed, ended their working relationship.

By the late 1930s, Fitzgerald's health problems and money worries made his years in Baltimore very difficult. He was hospitalized eight times between 1933 and 1937.

By 1937, Zelda's declining mental health meant she needed to stay for a long time at the Highland Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina. Almost broke, Fitzgerald spent most of 1936 and 1937 living in cheap hotels near Asheville. His attempts to write and sell more short stories failed. The death of Fitzgerald's mother and Zelda's health struggles caused his marriage to fall apart even more. He saw Zelda for the last time during a trip to Cuba in 1939. He returned to the United States, and his health worsened.

Return to Hollywood

Fitzgerald's serious money problems forced him to accept a good contract as a screenwriter with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) in 1937. This meant he had to move to Hollywood. Even though he earned his highest income ever that year (about $29,757.87, which is like $650,000 today), he spent most of it on Zelda's treatment and his daughter Scottie's school expenses. For the next two years, Fitzgerald rented a cheap room at the Garden of Allah bungalow on Sunset Boulevard.

Separated from Zelda, Fitzgerald tried to meet his first love, Ginevra King, when she visited Hollywood in 1938. "She was the first girl I ever loved," Fitzgerald told his daughter Scottie, "and I have faithfully avoided seeing her up to this moment to keep the illusion perfect." The meeting was not successful, and a disappointed Ginevra returned to Chicago.

Soon after, a lonely Fitzgerald began a relationship with gossip columnist Sheilah Graham. She was his last companion before he died. After having a heart attack, Fitzgerald was told by his doctor to avoid hard physical activity. Since he had to climb two flights of stairs to his apartment, he moved in with Graham, who lived on the ground floor.

Graham said that throughout their relationship, Fitzgerald felt constant guilt about Zelda's mental illness and her hospital stays.

During this last part of his career, Fitzgerald worked on screenplays. These included revisions for Madame Curie (1943) and some unused dialogue for Gone with the Wind (1939). He did not receive credit for these. His work on Three Comrades (1938) was his only credited screenplay. He often ignored script rules, writing descriptions more like a novel. In his free time, he worked on his fifth novel, The Last Tycoon, which was based on film executive Irving Thalberg. In 1939, MGM ended his contract, and Fitzgerald became a freelance screenwriter.

Director Billy Wilder said Fitzgerald's time in Hollywood was like "a great sculptor who is hired to do a plumbing job." Some suggested Hollywood drained Fitzgerald's creativity. His struggles in Hollywood led him to drink more.

Final Year and Death

Fitzgerald died at 44 years old from a heart condition. Only about thirty people attended his funeral. Among them were his daughter, Scottie, his agent Harold Ober, and his editor Maxwell Perkins.

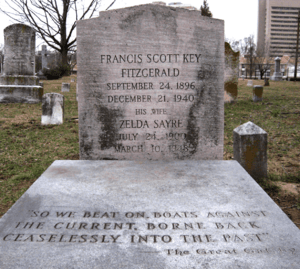

Zelda wrote about Fitzgerald in a letter to a friend: "He was as spiritually generous a soul as ever was... It seems as if he was always planning happiness for Scottie and for me. Books to read—places to go. Life seemed so promising always when he was around. ... Scott was the best friend a person could have to me." At the time of his death, the Roman Catholic Church did not allow Fitzgerald to be buried in the family plot at the Catholic Saint Mary's Cemetery in Rockville, Maryland. This was because he was not a practicing Catholic. Fitzgerald was buried instead with a simple Protestant service. When Zelda died in a fire in 1948, she was buried next to him. In 1975, Scottie successfully asked for her parents' remains to be moved to the family plot in Saint Mary's.

Fame After Death

The popularity of The Great Gatsby led to a lot of interest in Fitzgerald himself. By the 1950s, he became a very well-known figure in American culture. He was more famous after his death than he ever was during his lifetime.

Decades after he died, Fitzgerald's childhood home in St. Paul became a National Historic Landmark in 1971. Fitzgerald himself did not like the house, calling it an "architectural monstrosity." In 1990, Hofstra University started the F. Scott Fitzgerald Society. In 1994, the World Theater in St. Paul was renamed the Fitzgerald Theater.

His Influence and Legacy

How He Influenced Other Writers

Fitzgerald was one of the most important writers of the Jazz Age. His writing style influenced many writers, both during his time and later. As early as 1922, critic John V. A. Weaver said that Fitzgerald's influence was already "so great that it cannot be estimated."

Like writers such as Edith Wharton and Henry James, Fitzgerald often used a series of separate scenes to tell his stories. His editor, Max Perkins, said this technique made the reader feel like they were on a train journey. Each scene was vivid and full of life. Fitzgerald also often used a narrator to connect these scenes and give them deeper meaning, similar to Joseph Conrad.

The Great Gatsby remains Fitzgerald's most influential book. When it was published, poet T. S. Eliot said it was the most important step forward in American fiction since the works of Henry James. Charles Jackson, who wrote The Lost Weekend, said Gatsby was the only perfect novel in American literature. Later authors like Budd Schulberg and Edward Newhouse were greatly affected by it. John O'Hara also said it influenced his work. Richard Yates, a writer often compared to Fitzgerald, praised The Great Gatsby for showing Fitzgerald's amazing talent. The New York Times summarized Fitzgerald's big influence on writers and Americans during the Jazz Age: "In the literary sense he invented a 'generation' ... He might have interpreted them, and even guided them."

Famous Works

Novels

- 1920 – This Side of Paradise

- 1922 – The Beautiful and Damned

- 1922 – The Diamond as Big as the Ritz (A shorter novel)

- 1925 – The Great Gatsby

- 1934 – Tender Is the Night

- 1941 – The Last Tycoon (unfinished)

Short Stories

- 1920 – "The Ice Palace"

- 1920 – "Bernice Bobs Her Hair"

- 1920 – "May Day"

- 1922 – "The Curious Case of Benjamin Button"

- 1922 – "Winter Dreams"

- 1924 – "Absolution"

- 1926 – "The Rich Boy"

- 1931 – "Babylon Revisited"

Images for kids

-

With The Great Gatsby (1925), critics felt Fitzgerald had mastered novel writing.

-

Poet Edna St. Vincent Millay thought Fitzgerald was talented but did not always have important things to say in his stories.

See also

In Spanish: F. Scott Fitzgerald para niños

In Spanish: F. Scott Fitzgerald para niños

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |