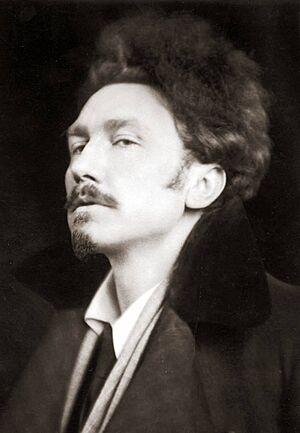

Ezra Pound facts for kids

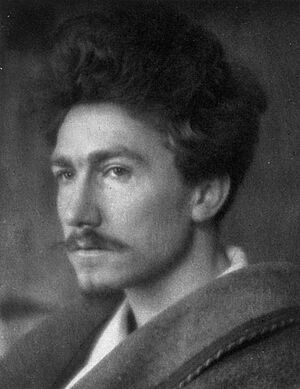

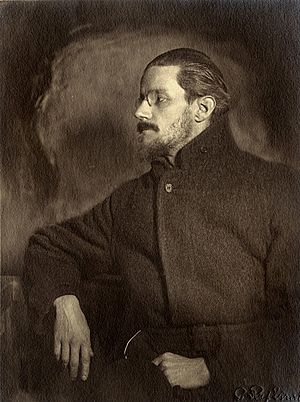

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (born October 30, 1885 – died November 1, 1972) was an American poet and critic who lived most of his life outside the United States. He was a very important person in the early modernist poetry movement. Modernist poetry was a new way of writing poems in the early 1900s. During World War II, he supported Fascism in Italy. Some of his most famous works include Ripostes (1912), Hugh Selwyn Mauberley (1920), and his very long poem, The Cantos (written from about 1917 to 1962).

Pound started making a big impact on poetry in the early 1900s. He helped create a style called Imagism. This style focused on using clear, exact language and not wasting words. While working in London, he helped other famous writers like T. S. Eliot, Ernest Hemingway, and James Joyce develop their work. He helped publish Joyce's A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in 1914 and Eliot's "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" in 1915. Ernest Hemingway once said that it would be impossible for poets of that time not to be influenced by Pound.

In 1924, Pound moved to Italy. During the 1930s and 1940s, he supported an economic idea called social credit. He also wrote for newspapers owned by a British fascist leader, Sir Oswald Mosley. Pound openly supported Benito Mussolini's fascist government and even spoke positively about Adolf Hitler. During World War II, he made many paid radio broadcasts for the Italian government. In these broadcasts, he criticized the United States, its president Franklin D. Roosevelt, Great Britain, and others. He was arrested in 1945 by American soldiers in Italy because of his actions. He spent several months in a U.S. military camp in Pisa, including three weeks in an outdoor steel cage. He was later found to be mentally unwell and was sent to St. Elizabeths Hospital, a psychiatric hospital in Washington, D.C., for over 12 years.

While he was held in Italy, Pound started writing parts of The Cantos. These were published as The Pisan Cantos in 1948. For this work, he won the Bollingen Prize for Poetry in 1949. After many writers campaigned for his release, he left St. Elizabeths in 1958. He lived in Italy until he passed away in 1972. His ideas about money and politics are still debated today, making his life and work quite controversial.

Contents

Growing Up and School (1885–1908)

Family Background

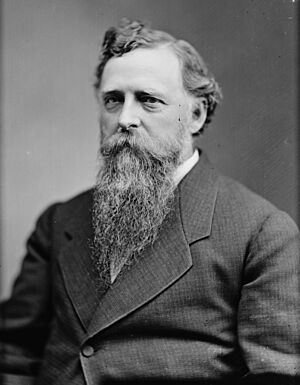

Ezra Pound was born in 1885 in a house in Hailey, Idaho. He was the only child of Homer Loomis Pound and Isabel Weston. His father worked for the government's land office. Ezra's grandfather, Thaddeus C. Pound, was a Republican Congressman and a Lieutenant Governor of Wisconsin. He helped Homer get his job.

Both sides of Pound's family came from England in the 1600s. His father's family were Quakers, and his mother's family were Puritans.

Early School Days

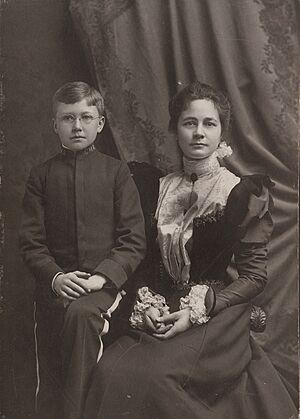

Ezra's mother, Isabel, did not like living in Hailey. She took Ezra to New York in 1887 when he was just 18 months old. His father followed and found a job at the Philadelphia Mint. The family later bought a house in Wyncote, Pennsylvania. Ezra started school in 1892. He was known as "Ra" (pronounced "Ray"). His first writing was a short, funny poem called a limerick published in a local newspaper in 1896 when he was 11.

In 1897, at age 12, he went to Cheltenham Military Academy. There, he wore a uniform like those from the American Civil War and learned how to drill and shoot. The next year, he went on his first trip overseas with his mother and aunt. They visited England, Belgium, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Spain, and Morocco. He stayed at the military academy until 1900 but did not graduate.

College Life

In 1901, Pound started at the University of Pennsylvania when he was 15. He later said he went there to avoid military training. His grades were mostly poor, except for geometry. He switched to a "non-degree special student status" to focus on subjects he found interesting. He was not invited to join a fraternity at Penn.

In 1902, his family took him on another three-month trip to Europe. The next year, he moved to Hamilton College in New York, possibly because of his grades. He hoped to join a fraternity there but was not invited. He studied the Provençal dialect (an old language from France) and read works by Dante Alighieri and old English poems like Beowulf.

After graduating from Hamilton in 1905, he returned to Penn. There, he fell in love with Hilda Doolittle, who also became a poet. He made a special book of his poems for her. After getting his master's degree in Romance languages in 1906, he planned to write a PhD paper. He traveled to Europe again, visiting libraries in Madrid, Paris, and London. In Madrid, he was near an attempted assassination of the King and left the city quickly. His first essay was published in September 1906. In 1907, he had disagreements with his English professors and left the university without finishing his doctorate.

Teaching Career

From September 1907, Pound taught French and Spanish at Wabash College in Indiana. He called the college "the sixth circle of hell". Some students liked him, calling him a "breath of fresh air," but others found him "egotistic."

He was fired after only a few months. Smoking was not allowed, but he smoked cigarillos in his room. He was asked to leave in January 1908 when his landladies found a woman in his room. Shocked, he soon left for Europe, sailing from New York in March.

London Life (1908–1914)

A Lume Spento and Moving to London

Pound arrived in Gibraltar in March 1908. He worked as a guide for an American family. After visiting other cities, he reached Venice by the end of April. That summer, he decided to publish his first collection of 44 poems, called A Lume Spento ("With Tapers Quenched"). He printed 150 copies in July 1908. The title comes from a poem by Dante Alighieri, hinting at death. Pound dedicated the book to a friend who had recently died.

He later wrote that he thought about throwing the printed pages into the Grand Canal and giving up poetry.

Settling in London

In August 1908, Pound moved to London with 60 copies of his book. At that time, English poetry was often grand and patriotic. Pound wanted to change this. He wanted poetry to focus on personal feelings and real things, not just ideas.

He first stayed in a boarding house near the British Museum Reading Room. He soon moved to a cheaper place in Islington, but then moved back to central London. He persuaded a bookseller to display A Lume Spento. In November 1908, he even wrote an unsigned review of his own book, saying it had "unseizable magic." The next month, he self-published another collection, A Quinzaine for this Yule, which sold well. In 1909, he gave lectures on literature at the Regent Street Polytechnic. He often spent mornings at the British Museum and had lunch at the Vienna Café, where he met other writers.

Meeting Dorothy and Personae

In 1909, Pound met Dorothy Shakespear at a literary gathering. She later became his wife in 1914. A critic described Dorothy as having a "clear and lovely" profile. Dorothy wrote in her diary about Pound, saying "Ezra! Ezra!—And a third time—Ezra!"

Pound became friends with many important writers in London, including W. B. Yeats. Yeats had already read Pound's first book and found it "charming." Pound wrote to a friend that London was the "place for poesy." Newspapers interviewed him, and he was even mentioned in Punch magazine.

In April 1909, his book Personae of Ezra Pound was published. It included poems from his first book. In October, another collection, Exultations, came out. A poet named Edward Thomas said Personae was "full of human passion." However, another poet, Rupert Brooke, felt Pound was too influenced by Walt Whitman and wrote in "unmetrical sprawling lengths."

Around September, Pound moved to new rooms in Kensington, where he lived until 1914. In 1910, he met Margaret Lanier Cravens in Paris, who offered to support him financially. She sent him money regularly until her death in 1912.

The Spirit of Romance and The New Age

In June 1910, Pound returned to the United States for eight months. His first book of literary criticism, The Spirit of Romance, was published in London around this time. He also wrote essays about the United States. He loved New York but felt bothered by the city's focus on money and the many new immigrants. He found the recently built New York Public Library Main Branch especially annoying. During this time, his dislike of Jewish people became clear. He wrote about the "detestable qualities" of Jews. After convincing his parents to pay for his trip, he sailed back to Europe in February 1911. He did not visit the U.S. again for nearly 30 years.

After a short stay in London, he went to Paris to work on a new poetry collection, Canzoni (1911). This book was criticized for its "stilted language." When he returned to London in August, he rented a room in Marylebone. By November, he was hired to write a weekly column for New Age, a socialist magazine. He met many important writers at meetings for the magazine, including H. G. Wells. In 1918, he met C. H. Douglas, a British engineer who had economic ideas that Pound liked. Douglas reportedly believed that Jewish people were a problem. The New Age magazine itself published some anti-Jewish material. It was in this environment that Pound first heard anti-Jewish ideas about "usury" (lending money at high interest).

Poetry Magazine and Imagism

Hilda Doolittle came to London in May 1911. Pound introduced her to his friends, including Richard Aldington, who later married her. The three of them lived close to each other in Kensington and worked daily at the British Museum Reading Room.

At the British Museum, Pound learned about East Asian art and literature. He was working on poems for Ripostes (1912), trying to write in a simpler style. He later said he was trying to "make a language" for himself.

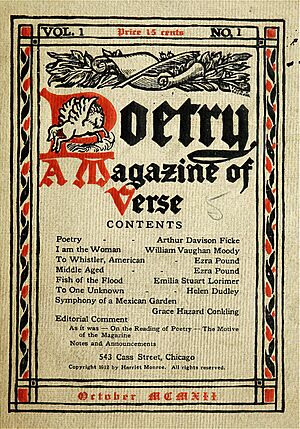

In August 1912, Harriet Monroe hired Pound to be the foreign correspondent for Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, a new magazine in Chicago. The first issue in October featured two of his poems. Also that month, Ripostes of Ezra Pound was published. This collection of 25 poems showed his move toward simpler language. It also included a debated translation of an old English poem, The Seafarer.

Ripostes was the first place where the term Les Imagistes was mentioned. One afternoon, while at the British Museum with Doolittle and Aldington, Pound edited one of Doolittle's poems and wrote "H.D. Imagiste" below it. He later said this was the start of the Imagisme poetry movement. In 1912, they agreed on three main ideas for Imagism:

- Use direct language.

- Avoid words that don't add to the meaning.

- Write in the rhythm of music, not a strict beat.

Pound's "A Few Don'ts by an Imagist" was published in Poetry in March 1913. He advised poets to avoid extra words, especially adjectives, and not to mix abstract ideas with concrete images. He wanted Imagism to be about "hard light, clear edges."

A famous example of Imagist poetry is Pound's "In a Station of the Metro". It was published in Poetry in April 1913. He wrote it after seeing beautiful faces in the Paris Underground and trying to find words for his feelings. He later shortened it to its core, like a Japanese haiku.

James Joyce and Pound's Popularity

In summer 1913, Pound became a literary editor for The Egoist magazine. W. B. Yeats suggested that Pound encourage James Joyce to send his work. Pound and Yeats spent three winters together at Stone Cottage, where Yeats introduced Pound to Joyce's poems and early novel chapters.

Around this time, Pound's articles in The New Age started making him unpopular. People found him stubborn, bossy, and lacking humor. He wrote that English women were not as smart as American women and that London had lost its energy. He also said that England's best writers were not English.

Marriage Life

Ezra and Dorothy were married on April 20, 1914, in Kensington. Her parents were against it because they worried about Ezra's income. Dorothy had some money of her own, and Ezra's father also supported him. After the wedding, they moved into an apartment next door to Hilda Doolittle and Richard Aldington. This arrangement did not last long, as Ezra's habits bothered H.D., and she and Aldington moved away.

World War I and Leaving England (1914–1921)

Meeting T. S. Eliot and Cathay

When World War I began in August 1914, it became harder for writers to get published. Poems were expected to be patriotic. Pound's income dropped a lot.

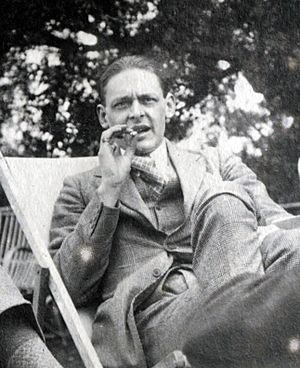

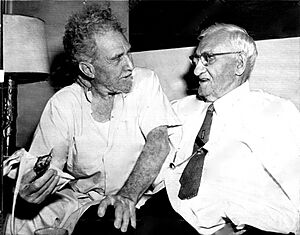

On September 22, 1914, T. S. Eliot came to Pound to have him read his poem "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock". Pound wrote to Harriet Monroe, the editor of Poetry, saying Eliot's poem was the "best poem I have yet had or seen from an American." Monroe published it in June 1915.

Pound's book Cathay, published in April 1915, contained 25 Chinese poems that Pound translated into English. He used notes from an expert named Ernest Fenollosa. Some people argue whether these poems should be seen as true translations or as examples of Imagism.

Pound's translations from old English, Latin, Italian, French, and Chinese were often debated. Some critics said he didn't know enough of the original languages.

Pound was very sad when Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, a sculptor he admired, was killed in the war in June 1915. Pound published a book about him, saying "A great spirit has been among us."

"Three Cantos" and Leaving Poetry

After Cathay was published, Pound started working on a very long poem, which he called a "cryselephantine poem of immeasurable length." In June, July, and August 1917, the first three parts of this poem, called "Three Cantos," were published in Poetry magazine.

Pound also wrote music and art reviews for other magazines. He became the foreign editor of the Little Review in May 1917. He wrote many articles complaining about narrow-mindedness, even about church bells ringing too loudly. All this writing made him very tired. In 1918, after being sick, he decided to stop writing for the Little Review.

By June 1918, people suspected Pound had written an article in The Egoist praising his own work. It was clear he had made enemies. A poet named F. S. Flint said that British literary circles were "tired of his antics" and wished he would "go back to America."

In March 1919, Poetry published Pound's Poems from the Propertius Series, which seemed to be a translation of a Latin poet.

Hugh Selwyn Mauberley

He strove to resuscitate the dead art

Of poetry; to maintain "the sublime"

In the old sense. Wrong from the start—

No hardly, but, seeing he had been born

In a half savage country, out of date;

Bent resolutely on wringing lilies from the acorn;

Capaneus; trout for factitious bait;

Ἴδμεν γάρ τοι πάνθ', ὅσ 'ένι Τροίη

Caught in the unstopped ear;

Giving the rocks small lee-way

The chopped seas held him, therefore, that year.

By 1919, Pound felt he had no reason to stay in England. He had become "violently hostile" to England, feeling he was being ignored. He believed the British did not appreciate "mental agility." Richard Aldington wrote that Pound had "muffed his chances of becoming literary director of London" because of his "enormous conceit, folly, and bad manners."

Pound's poem Hugh Selwyn Mauberley was published in June 1920. It was his way of saying goodbye to London. By December, the Pounds were getting ready to move to France. Mauberley has 18 short parts and describes a poet whose life has become empty. It starts with a funny look at the London literary scene before moving to social criticism and the war. The word usury (lending money at very high interest) first appears in his work here. Pound said the poem was not about himself. A critic later called Mauberley "great poetry."

In January 1921, the editor of The New Age wrote that Pound had left London without much thanks. He said Pound had been a "stimulating influence for culture in England" and had left his mark on literature, music, poetry, and sculpture.

Paris Years (1921–1924)

Meeting Hemingway and Editing The Waste Land

The Pounds settled in Paris around April 1921. Pound became friends with artists and writers like Marcel Duchamp and Tristan Tzara. He also met the American writer Gertrude Stein, who said she liked him but found him a "village explainer."

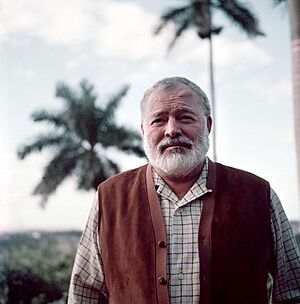

Pound's collection Poems 1918–1921 was published in New York in 1921. In December of that year, Ernest Hemingway, then 22, moved to Paris. Hemingway and Pound became friends, even though Pound was 14 years older. Hemingway looked up to Pound and asked him to edit his short stories. Pound introduced Hemingway to his contacts, while Hemingway tried to teach Pound how to box. Pound was not a big drinker and preferred to spend his time at literary gatherings or building furniture.

In 1922, T. S. Eliot sent Pound the manuscript of The Waste Land. Pound edited it, cutting it by about half. Eliot later wrote that Pound's editing showed his "critical genius." Eliot dedicated The Waste Land to Pound, calling him "the better craftsman."

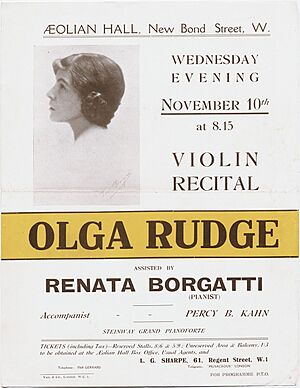

Meeting Olga Rudge

Pound was 36 when he met 26-year-old American violinist Olga Rudge in Paris in the summer of 1922. They met at a gathering hosted by an American heiress. They came from different social worlds: Rudge was from a wealthy family and socialized with aristocrats, while Pound's friends were mostly struggling writers.

Restarting The Cantos

Pound's 800-page poem, The Cantos, became his life's work. It is much longer than many famous poems. The first three parts were published in 1917, but in 1922, Pound started over. He said The Cantos was like the different voices you hear when you turn a radio dial.

The poem refers to American, European, and Asian art, history, and literature. It also tells parts of Pound's own life story. Some people see it as a religious poem about humanity's journey from hell to paradise. Others have criticized it for lacking clear structure. Pound himself wrote in the final complete part, "Canto CXVI," that he could not "make it cohere" (make it fit together), but then added, "it coheres all right."

Life in Italy (1924–1939)

Birth of His Children

The Pounds were not happy in Paris, and Ezra's health was poor. In October 1924, they moved to Rapallo, a quiet seaside town in northern Italy. Ezra had a "small nervous breakdown" while packing.

Olga Rudge, who was pregnant with Pound's child, followed them to Italy. In July 1925, she gave birth to a daughter, Maria, in a hospital. Rudge and Pound placed the baby with a German-speaking peasant woman who agreed to raise Maria. Pound reportedly believed that artists should not have children because he thought motherhood changed women too much.

In May 1926, the Pounds and Olga Rudge went to Paris for a concert of an opera Pound had composed. Dorothy Pound was pregnant and wanted her baby to be born at the American hospital in Paris. Their son, Omar Pound, was born on September 10, 1926. Dorothy took Omar to England, where he lived with a nanny and later went to boarding school. When Dorothy was in England, Ezra spent time with Olga. Olga's father helped her buy a house in Venice in 1928.

The Exile and Awards

In 1925, a new literary magazine, This Quarter, dedicated its first issue to Pound. Ernest Hemingway wrote that Pound spent only a small part of his time writing poetry but produced "a large and distinguished share of the really great poetry."

However, Richard Aldington said that Pound was almost forgotten in England. In the U.S., Pound won the $2,000 Dial poetry award in 1927 for his translation of a Confucian classic. He used the prize money to start his own literary magazine, The Exile, but only four issues were published. His parents visited him in Rapallo that year, seeing him for the first time since 1914. They later moved to Rapallo themselves.

Meeting Mussolini

In December 1932, Pound asked to meet Benito Mussolini, the leader of Italy. They met on January 30, 1933, in Rome, the same day Hitler became Chancellor of Germany.

Pound gave Mussolini a copy of his poem A Draft of XXX Cantos. Mussolini reportedly said a part Pound highlighted was not English. Pound replied, "No, it's my idea of the way a continental Jew would speak English." Pound tried to discuss his economic ideas with Mussolini. Pound later wrote that he had "never met anyone who seemed to get my ideas so quickly as the boss." He felt he had become an important person. When he returned to Rapallo, the town band greeted him.

After the meeting, Pound quickly wrote books like The ABC of Economics and Jefferson and/or Mussolini (1935). He also wrote articles praising Mussolini and fascism for various newspapers.

Pound's anti-Jewish views became stronger when Italy introduced racial laws in 1938. These laws placed restrictions on Jewish people. Mussolini declared Judaism "an irreconcilable enemy of fascism."

Visit to America

In October 1938, Pound's former mother-in-law, Olivia Shakespear, died in London. Ezra went to her funeral and saw his 12-year-old son, Omar, for the first time in eight years. He also visited T. S. Eliot and Wyndham Lewis.

Pound believed he could stop America from joining World War II. In April 1939, he sailed to New York in a first-class suite. He told reporters that Mussolini wanted peace. In Washington, D.C., he tried to convince senators and congressmen. He wanted to meet the President but was told he could not.

He gave a poetry reading at Harvard and received an honorary degree from Hamilton College. At Hamilton, he loudly interrupted an anti-fascist speech. Pound sailed back to Italy a few days later.

Between May and September 1939, Pound wrote articles for Japan Times. He claimed that "Democracy is now currently defined in Europe as a 'country run by Jews'." He also praised "Hitler's war aims" and said Churchill was controlled by the Rothschild family.

World War II and Radio Broadcasts (1939–1945)

Letter Writing

When World War II started in September 1939, Pound began writing many letters to politicians. He wrote to a senator, saying that "the dirtiest jews from Paris" should not be allowed into the U.S. He also wrote to his publisher that "Roosevelt represents Jewry" and signed off with "Heil Hitler." He started calling President Roosevelt "Jewsfeldt." He compared Hitler and Mussolini to Confucius. He wrote in a newspaper that the English were "a slave race governed by the House of Rothschild." By May 1940, the British government saw Pound as a main source of information for British fascists. His literary agent asked him to go back to writing poetry, but Pound sent him political writings instead.

Radio Broadcasts

Between January 1941 and March 1945, Pound recorded or wrote hundreds of broadcasts for Italian radio. These broadcasts were in English, and sometimes in Italian, German, and French. They were sent to England, Europe, and the United States.

Calling himself "Dr Ezra Pound," he attacked the United States, President Roosevelt, Churchill, and Jewish people, while praising Hitler. The U.S. government monitored these broadcasts. In July 1943, Pound was charged with treason. Records show that Pound received payments from the Italian government for his broadcasts.

In September 1943, German soldiers took control of northern and central Italy. Hitler made Mussolini the head of a new fascist state. German officers began gathering Jewish people to send them to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Pound was in Rome when the German occupation began. He traveled north to visit his daughter. In November 1943, he met the new Minister of Popular Culture. Pound later asked his wife if she could get a radio confiscated from Jewish people to help with his work.

From December 1943, Pound started writing scripts for the new state radio station. He also suggested that bookstores should be legally required to display certain books, including The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a fake document claiming to be a Jewish plan to control the world.

Arrest for Treason

Mussolini was killed in April 1945. In May, armed Italian fighters arrived at Olga Rudge's home and found Pound alone. He was taken to the U.S. Counter Intelligence Corps headquarters in Genoa, where he was questioned.

Pound asked to send a message to President Truman to help negotiate peace with Japan. He wanted to make a final broadcast recommending peace with Japan, American management of Italy, a Jewish state in Palestine, and kindness toward Germany. His requests were denied. A few days later, an FBI agent took over 7,000 of Pound's letters and documents as evidence. On May 8, the day Germany surrendered, Pound gave the Americans another statement.

Later that day, he told a reporter that Hitler was "a Jeanne d'Arc" (like Joan of Arc) and that Mussolini was "a very human, imperfect character." On May 24, he was moved to a U.S. Army camp in Pisa. He was placed in a small, outdoor steel cage, lit up at night. Engineers made his cage stronger because they worried fascist supporters might try to free him.

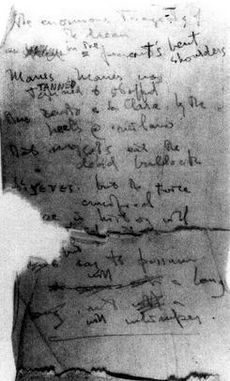

Pound lived alone in the heat, sleeping on concrete. He was not allowed to exercise or talk to anyone except the chaplain. After three weeks, he stopped eating. Medical staff moved him out of the cage the next week. He was examined by psychiatrists and then moved to his own tent. He began to write, starting what became The Pisan Cantos. The first lines of "Canto LXXIV" were found on toilet paper, suggesting he started writing in the cage.

United States (1945–1958)

St. Elizabeths Hospital

Pound arrived in Washington, D.C., on November 18, 1945. He was charged with treason on November 27 and placed in a locked room in a psychiatric ward. Three psychiatrists decided he was mentally unfit to stand trial. They found him "abnormally grandiose" and easily distracted.

On December 21, 1945, he was moved to Howard Hall, a maximum-security ward at St. Elizabeths Hospital. He was held in a single cell. A hearing in February 1946 concluded he was "of unsound mind." As a compromise, he was moved to a more comfortable ward. Later, he was moved to a larger room in Chestnut Ward.

Pound seemed to thrive in Chestnut Ward. He was allowed to read, write, and have visitors, including his wife Dorothy. His room had a typewriter, bookshelves, and notes for The Cantos hanging from the ceiling. He even turned a small area into a living room where he entertained friends and writers. He refused to discuss being released.

The Pisan Cantos and Bollingen Prize

James Laughlin, Pound's publisher, had The Pisan Cantos ready for publication in 1946. A group of Pound's friends, including T. S. Eliot, met to discuss how to get Pound released. They planned to have him awarded the first Bollingen Prize, a new national poetry award with $1,000 prize money.

The awards committee included several of Pound's supporters. The idea was that if Pound won a major award, the government would find it hard to keep him locked up. Laughlin published The Pisan Cantos in July 1948, and Pound won the prize the following February. There was a lot of public outrage because of Pound's anti-Jewish views. Critics said poetry should not "convert words into maggots that eat at human dignity." A Congressman demanded an investigation. This was the last time the Library of Congress managed the prize.

Diagnosis and Release

In January 1946, psychiatrists at St. Elizabeths concluded that Pound had a psychopathic personality disorder but was not psychotic. He lay on the floor during the interview. In 1953, a psychiatrist added that Pound likely had narcissistic personality disorder, meaning he was extremely self-centered. A personality disorder is not considered a mental illness, which would have made him fit for trial. However, in 1955, his diagnosis was changed to "psychotic disorder," which is a mental illness. After his release, in 1966, he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

Pound's friends kept trying to get him out of St. Elizabeths. Olga Rudge published some of his radio broadcasts (only the cultural ones) to show they were harmless. She visited him but couldn't convince him to push for his release. In 1950, she complained to Hemingway that Pound's friends weren't doing enough. Hemingway replied that Pound had "made the rather serious mistake of being a traitor to his country."

Four years later, after winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954, Hemingway told Time magazine that it would be a good year to release poets. He later signed a letter asking for Pound's release and pledged money to him.

Several publications started campaigning in 1957. Le Figaro published an appeal called "The Lunatic at St Elizabeths." The Nation argued that Pound was a "sick and vicious old man" but still had rights. In 1958, a lawyer filed a motion to dismiss the treason charges. The hospital superintendent supported the request, saying Pound was incurably insane and confinement served no purpose. The motion was approved, and Pound was released on May 7.

Italy Again (1958–1972)

Depression and Decline

Pound and Dorothy arrived in Naples in July 1958. Pound was photographed giving a fascist salute to the press. When asked about his release from the mental hospital, he said, "I never was. When I left the hospital I was still in America, and all America is an insane asylum." They were joined by a young teacher, Marcella Spann, who acted as his secretary. They lived with his daughter Mary at Schloss Brunnenburg, where Pound met his grandchildren for the first time. Dorothy used her legal power over his money to make sure Spann was sent back to the United States.

By December 1959, Pound was very depressed. A writer who visited him said Pound was a changed man, spoke little, and called his work "worthless." In a 1960 interview, he said, "You—find me—in fragments." He seemed to doubt the value of everything he had done.

Those close to him thought he had dementia. In mid-1960, he spent time in a clinic because he lost a lot of weight. His health continued to decline. Dorothy felt she could not care for him, so he went to live with Olga Rudge. His friends were also dying around this time. In 1963, he told an interviewer, "I spoil everything I touch... All my life I believed I knew nothing... And so words became devoid of meaning."

In 1966, he was admitted to a psychiatric hospital for evaluation. His doctors diagnosed him with bipolar disorder. Two years later, he attended an exhibition in New York and received a standing ovation at Hamilton College.

Death

Shortly before his death in 1972, a committee proposed that Pound be awarded a medal. After many protests, the idea was rejected.

On his 87th birthday, October 30, 1972, he was too weak to leave his room. The next night, he was taken to a hospital in Venice, where he died in his sleep on November 1 from an "intestinal blockage." His wife, Dorothy, requested a Protestant funeral. However, Olga Rudge had already made plans. Pound's son, Omar, arrived too late. Four gondoliers in black rowed Pound's body to Venice's cemetery, Isola di San Michele. He was buried near other non-Italian Christians. Dorothy Pound died the next year. Olga Rudge died in 1996 and was buried next to Pound.

Selected Works

- (1908). A Lume Spento. (poems)

- (1908). A Quinzaine for This Yule. (poems)

- (1909). Personae. (poems)

- (1909). Exultations. (poems)

- (1910). The Spirit of Romance. (prose)

- (1910). Provenca. (poems)

- (1911). Canzoni. (poems)

- (1912). The Sonnets and Ballate of Guido Cavalcanti. (translations)

- (1912). Ripostes. (poems; first mention of Imagism)

- (1915). Cathay. (poems; translations)

- (1916). Gaudier-Brzeska. A Memoir. (prose)

- (1916). Certain Noble Plays of Japan: From the Manuscripts of Ernest Fenollosa.

- (1916) with Ernest Fenollosa. "Noh", or, Accomplishment: A Study of the Classical Stage of Japan.

- (1916). Lustra. (poems)

- (1917). Twelve Dialogues of Fontenelle. (translations)

- (1917). Lustra. (poems, with the first "Three Cantos")

- (1918). Pavannes and Divisions. (prose)

- (1918). Quia Pauper Amavi. (poems)

- (1919). The Fourth Canto. (poem)

- (1920). Hugh Selwyn Mauberley. (poem)

- (1920). Umbra. (poems and translations)

- (1920) with Ernest Fenollosa. Instigations: Together with an Essay on the Chinese Written Character. (prose)

- (1921). Poems, 1918–1921.

- (1922). Remy de Gourmont: The Natural Philosophy of Love. (translation)

- (1923). Indiscretions, or, Une revue des deux mondes.

- (1924) as William Atheling. Antheil and the Treatise on Harmony. (essays)

- (1925). A Draft of XVI Cantos. (first collection of The Cantos)

- (1926). Personae: The Collected Poems of Ezra Pound.

- (1928). A Draft of the Cantos 17–27.

- (1928). Selected Poems.

- (1928). Ta Hio: The Great Learning, newly rendered into the American language. (translation)

- (1930). A Draft of XXX Cantos.

- (1930). Imaginary Letters.

- (1931). How to Read. (essays)

- (1932). Guido Cavalcanti Rime. (translations)

- (1933). ABC of Economics. (essays)

- (1934). Eleven New Cantos: XXXI–XLI. (poems)

- (1934). Homage to Sextus Propertius. (poems)

- (1934). ABC of Reading. (essays)

- (1934). Make It New. (essays)

- (1935). Alfred Venison's Poems: Social Credit Themes by the Poet of Titchfield Street. (essays)

- (1935). Jefferson and/or Mussolini. (essays)

- (1935). Social Credit: An Impact. (essays)

- (1936) with Ernest Fenollosa. The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry.

- (1937). The Fifth Decade of Cantos. (poems)

- (1937). Polite Essays. (essays)

- (1937). Confucius: Digest of the Analects. (translations)

- (1938). Guide to Kulchur.

- (1939). What Is Money For?. (essays)

- (1940). Cantos LXII–LXXI. (John Adams Cantos 62–71)

- (1942). Carta da Visita di Ezra Pound. (essays)

- (1944). L'America, Roosevelt e le cause della guerra presente. (essays)

- (1944). Introduzione alla Natura Economica degli S.U.A.. (essay)

- (1944). Orientamenti. (prose)

- (1944). Oro et lavoro: alla memoria di Aurelio Baisi. (essays)

- (1948). If This Be Treason. (original drafts of six of Pound's Radio Rome broadcasts)

- (1948). The Pisan Cantos. (Cantos 74–84)

- (1948). The Cantos of Ezra Pound. (includes The Pisan Cantos)

- (1949). Elektra. (play)

- (1950). Seventy Cantos.

- (1950). Patria Mia. (reworked New Age articles, 1912–1913)

- (1951). Confucius: The Great Digest and Unwobbling Pivot. (translation)

- (1951). Confucius: Analects. (translation)

- (1954). The Classic Anthology Defined by Confucius. (translations)

- (1954). Lavoro ed Usura. (essays)

- (1955). Section: Rock-Drill, 85–95 de los Cantares. (poems)

- (1956). Sophocles: The Women of Trachis. A Version by Ezra Pound. (translation)

- (1957). Brancusi. (essay)

- (1959). Thrones: 96–109 de los Cantares. (poems)

- (1968). Drafts and Fragments: Cantos CX–CXVII. (poems)

See also

In Spanish: Ezra Pound para niños

In Spanish: Ezra Pound para niños

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |