Marcel Duchamp facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Marcel Duchamp

|

|

|---|---|

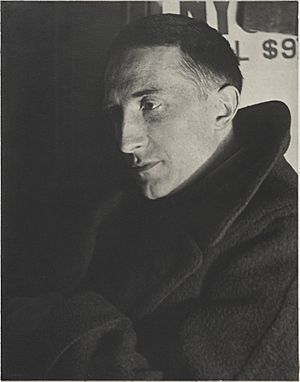

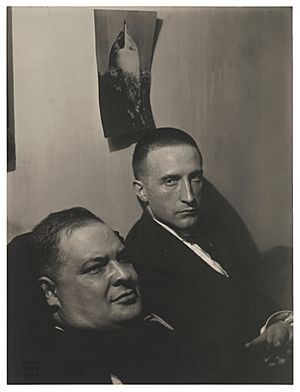

Portrait of Marcel Duchamp, 1920–21

by Man Ray, Yale University Art Gallery |

|

| Born |

Henri-Robert-Marcel Duchamp

28 July 1887 Blainville-Crevon, France

|

| Died | 2 October 1968 (aged 81) Neuilly-sur-Seine, France

|

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture, film |

|

Notable work

|

Fountain (1917) The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even (1915–1923) LHOOQ (1919) Étant donnés (1946–1966) |

| Movement | Cubism, Dada, conceptual art |

| Spouse(s) | Lydie Sarazin-Lavassor (1927–1928, divorced) Alexina "Teeny" Sattler (1954–1968, his death) |

| Partner(s) | Mary Reynolds (1929–1946) Maria Martins (1946–1951) |

Marcel Duchamp (born Henri-Robert-Marcel Duchamp; 28 July 1887 – 2 October 1968) was a French artist. He was a painter, sculptor, and writer. His work is linked to Cubism, Dada, and conceptual art. Many people see him, along with Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, as one of the most important artists of the early 1900s. He changed how people thought about painting and sculpture. Duchamp had a huge impact on art in the 20th and 21st centuries. He especially influenced conceptual art, which focuses on ideas more than the art object itself. By the time of World War I, he felt that many artists, like Henri Matisse, made "retinal" art. This meant art that only pleased the eye. Instead, Duchamp wanted art to make people think.

Contents

- Marcel Duchamp: Early Life and Family

- Marcel Duchamp: Early Artworks

- Marcel Duchamp: Moving Beyond "Retinal Art"

- Marcel Duchamp: What Are Readymades?

- Marcel Duchamp: The Large Glass Artwork

- Marcel Duchamp: Kinetic Art and Movement

- Marcel Duchamp: Musical Ideas

- Marcel Duchamp: Rrose Sélavy, His Other Self

- Marcel Duchamp: From Art to Chess

- Marcel Duchamp: Later Art Activities

- Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés

- Marcel Duchamp: Personal Life

- Marcel Duchamp: Death and Burial

- Marcel Duchamp: His Legacy in Art

- Marcel Duchamp: Selected Works

- See also

Marcel Duchamp: Early Life and Family

Marcel Duchamp was born in Blainville-Crevon, France. His parents were Eugène and Lucie Duchamp. He grew up in a family that loved art and culture. His grandfather, Émile Frédéric Nicolle, was a painter and engraver. His art filled their home. The family enjoyed playing chess, reading, painting, and making music together.

Marcel had six brothers and sisters. One died as a baby, but four of them became successful artists:

- Jacques Villon (1875–1963), a painter and printmaker.

- Raymond Duchamp-Villon (1876–1918), a sculptor.

- Suzanne Duchamp-Crotti (1889–1963), a painter.

When Marcel was a child, his older brothers were away at school. He was very close to his sister Suzanne. She often joined in his imaginative games. At eight years old, Marcel went to school at the Lycée Pierre-Corneille in Rouen. Two of his classmates also became famous artists and lifelong friends: Robert Antoine Pinchon and Pierre Dumont. Marcel studied there for eight years. He wasn't the best student, but he was good at math. He won two math prizes and a drawing prize in 1903. In 1904, he won a top prize, which helped him decide to become an artist.

He learned drawing from a teacher who tried to keep students away from new art styles. These included Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. But Marcel's real art guide was his brother Jacques Villon. Marcel tried to copy Jacques's clear and flowing style. At 14, Marcel's first serious artworks were drawings and watercolors of his sister Suzanne. That summer, he also painted landscapes using oils in an Impressionist style.

Marcel Duchamp: Early Artworks

Duchamp's first artworks were in the style of Post-Impressionism. He tried out classic art methods and subjects. When asked about his early influences, Duchamp mentioned Symbolist painter Odilon Redon. Redon's art was quiet and personal, not against traditional art.

He studied art at the Académie Julian from 1904 to 1905. But he liked playing billiards more than going to class. During this time, Duchamp drew and sold funny cartoons. Many of his drawings used wordplay or visual jokes. This love for playing with words and symbols stayed with him his whole life.

In 1905, he started his required military service. He worked for a printer in Rouen. There, he learned about typography and printing. These skills helped him in his later art.

His oldest brother, Jacques, was part of the important Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture. Because of this, Duchamp's work was shown in the 1908 Salon d'Automne. The next year, it was in the Salon des Indépendants. His paintings were influenced by Fauves and Paul Cézanne's early Cubism. The art critic Guillaume Apollinaire, who later became his friend, didn't always like his work. Duchamp also became lifelong friends with the lively artist Francis Picabia in 1911. Picabia introduced him to a fast-paced, exciting lifestyle.

In 1911, the Duchamp brothers hosted a group at Jacques' home in Puteaux. This group included Cubist artists like Picabia, Robert Delaunay, and Fernand Léger. Poets and writers also joined. The group was known as the Puteaux Group. Duchamp wasn't interested in the Cubists' serious talks about art theory. He was known for being shy. However, that same year, he painted in a Cubist style. He added a sense of motion by repeating images.

During this time, Duchamp became fascinated with change, movement, and distance. Like many artists then, he was interested in showing the fourth dimension in art. In his 1911 Portrait of Chess Players, he used Cubist overlapping and multiple views of his two brothers playing chess. But Duchamp also added things that showed the players' unseen thoughts.

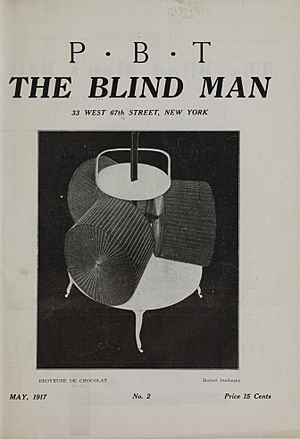

His works from this time also included his first "machine" painting, Coffee Mill (1911). He gave it to his brother Raymond. A later painting, Chocolate Grinder (1914), showed a machine more clearly. This painting hinted at the machine parts he would use in his Large Glass artwork later.

Marcel Duchamp: Moving Beyond "Retinal Art"

Around this time, Duchamp read a book by Max Stirner called The Ego and Its Own. He felt this book was a major turning point for his art and ideas. He said it was "a remarkable book... which advances no formal theories, but just keeps saying that the ego is always there in everything."

In 1912, while in Munich, Germany, he painted his last Cubist-like paintings. He started working on The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even and planned for The Large Glass. He wrote notes and made quick sketches. This big artwork would take more than ten years to finish. Duchamp was influenced by the 16th-century German painter Lucas Cranach the Elder. He visited the museum with Cranach's paintings every day. Art experts have noticed that Duchamp later used similar muted colors, like ochre and brown.

That same year, Duchamp saw a play based on Raymond Roussel's novel Impressions d'Afrique. The play had confusing plots, word games, strange sets, and human-like machines. Duchamp said this play completely changed his view on art. It inspired him to start The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even, also known as The Large Glass. He continued working on The Large Glass in 1913. He created many new shapes and forms. He made notes, sketches, and even drew ideas on his apartment wall.

Late in 1912, he traveled with Picabia and Apollinaire through the Jura Mountains. One friend described this trip as "forays of demoralization, which were also forays of witticism and clownery... the disintegration of the concept of art." Duchamp's notes from this trip were strange and dreamlike, avoiding normal logic.

After 1912, Duchamp painted very few canvases. In those he did paint, he tried to remove "painterly" effects. He wanted them to look more like technical drawings.

His wide interests led him to an aviation technology exhibit. After seeing it, Duchamp told his friend Constantin Brâncuși, "Painting is washed up. Who will ever do anything better than that propeller? Tell me, can you do that?". Brâncuși later made sculptures of bird forms. US Customs officials thought they were airplane parts and tried to charge import taxes on them.

In 1913, Duchamp stepped away from painting groups. He started working as a librarian at the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. This allowed him to earn money while focusing on his studies and Large Glass. He studied math and physics, fields where exciting new discoveries were happening. The ideas of Henri Poincaré especially interested him. Poincaré suggested that the rules we think govern matter are only created by our minds. He believed no theory could be truly "true." Poincaré wrote, "The things themselves are not what science can reach..., but only the relations between things. Outside of these relations there is no knowable reality." Because of Poincaré's ideas, Duchamp believed that any interpretation of his art was valid. He saw it as the viewer's creation, not a single truth.

Duchamp's own art-science experiments began at the library. For one of his favorite pieces, 3 Standard Stoppages (1913), he dropped three 1-meter threads onto prepared canvases from a height of 1 meter. The threads landed in wavy, random shapes. He glued them onto blue-black canvas strips and attached them to glass. Then he cut three wooden slats to match the curved shapes of the strings. He put all the pieces into a croquet box. Small leather signs with the title were glued to the backgrounds. This piece seemed to follow Poincaré's ideas about how things relate to each other.

In his studio, he put a bicycle wheel upside down on a stool. He would spin it sometimes just to watch it. This Bicycle Wheel is often seen as the first of his "Readymades". However, this specific setup was never shown in an art exhibit and was later lost. At first, the wheel was just in his studio to create a certain feeling: "I enjoyed looking at it just as I enjoy looking at the flames dancing in a fireplace."

When World War I began in August 1914, Duchamp felt uneasy in Paris. His brothers and many friends were in the military, but he was excused due to a heart condition. So, Duchamp decided to move to the United States in 1915. He was surprised to find he was famous when he arrived in New York. He quickly became friends with art supporter Katherine Sophie Dreier and artist Man Ray. Duchamp's friends included art supporters Louise and Walter Conrad Arensberg, actress Beatrice Wood, and Francis Picabia. He also met other modern artists. Even though he spoke little English, he quickly learned the language by giving French lessons and working in a library. Duchamp became part of an artist community in Ridgefield, New Jersey, across the Hudson River from New York City.

For two years, the Arensbergs, who stayed his friends for 42 years, let him use their studio. Instead of paying rent, Duchamp agreed to give them The Large Glass. An art gallery offered Duchamp $10,000 a year for all his new art, but he said no. He wanted to keep working on The Large Glass.

Société Anonyme: Supporting Modern Art

In 1920, Duchamp, Katherine Dreier, and Man Ray started the Société Anonyme. This group marked the start of his long involvement in buying and selling art. The group collected modern artworks. They also organized modern art shows and talks throughout the 1930s.

By this time, Walter Pach, who helped organize the 1913 Armory Show, asked Duchamp for advice on modern art. Dreier also relied on Duchamp's advice for her collection. Later, Peggy Guggenheim and directors from the Museum of Modern Art also asked Duchamp for his thoughts on modern art collections and shows.

Dada: Art That Questioned Everything

Dada was an art movement that started in Europe in the early 1900s. It began in Zurich, Switzerland, in 1916. It quickly spread to Berlin.

Dada involved visual arts, writing, poetry, and theater. It focused on anti-war ideas. Dada artists rejected common art rules through "anti-art" works. Besides being anti-war, Dada was also against the wealthy middle class. It had links to radical political groups.

Dada activities included public events and publishing art magazines. These magazines often discussed art, politics, and culture. Key Dada artists included Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, Hans Arp, and Tristan Tzara. The movement influenced later art styles like surrealism and pop art.

The Dada movement in New York was less serious than in Europe. It wasn't very organized. Duchamp's friend Francis Picabia connected with the Zurich Dada group. He brought Dada ideas of silliness and "anti-art" to New York. Duchamp and Picabia first met in Paris in 1911. Duchamp said, "our friendship began right there." A group of artists met almost every night at the Arensberg home or in Greenwich Village. Duchamp and Man Ray added their ideas and humor to the New York Dada scene. Many of these activities happened while Duchamp was creating his Readymades and The Large Glass.

The most famous example of Duchamp's Dada connection was his artwork Fountain. This was a urinal he submitted to an art show in 1917. Artworks in this show were not chosen by a jury; all submitted pieces were supposed to be displayed. However, the show committee said Fountain was not art and rejected it. This caused a big stir among the Dada artists. Duchamp then resigned from the show's board.

With Henri-Pierre Roché and Beatrice Wood, Duchamp published several Dada magazines in New York. These included The Blind Man and Rongwrong. They featured art, writing, humor, and comments on society. When Duchamp returned to Paris after World War I, he did not join the Dada group there.

Marcel Duchamp: What Are Readymades?

"Readymades" were everyday objects that Duchamp chose and presented as art. In 1913, Duchamp put a Bicycle Wheel in his studio. The idea for this came from Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. However, the full idea of "Readymades" didn't develop until 1915. The goal was to question what art really is. Duchamp felt that people admired art too much, which he found "unnecessary."

Bottle Rack (1914), a bottle-drying rack signed by Duchamp, is seen as the first "pure" readymade. In Advance of the Broken Arm (1915), a snow shovel, came soon after. His Fountain, a urinal signed with the fake name "R. Mutt," shocked the art world in 1917. In 2004, 500 famous artists and historians voted Fountain "the most influential artwork of the 20th century."

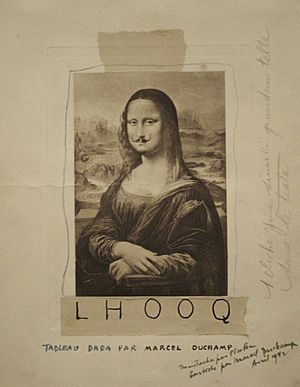

In 1919, Duchamp made a funny version of the Mona Lisa. He drew a mustache and goatee on a cheap copy of the painting. Some say the Mona Lisa copy was actually based partly on Duchamp's own face.

Marcel Duchamp: The Large Glass Artwork

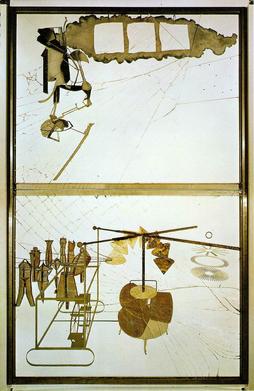

Duchamp worked on his complex, Futurism-inspired artwork, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (also called The Large Glass), from 1915 to 1923. He took breaks when he was in Buenos Aires and Paris. He made the artwork on two large panes of glass. He used materials like lead foil, fuse wire, and even dust.

A play based on Raymond Roussel's novel Impressions d'Afrique, which Duchamp saw in 1912, inspired this piece. Notes, sketches, and plans for the work were drawn on his studio walls as early as 1913. To focus on the work without money worries, Duchamp worked as a librarian in France. After moving to the United States in 1915, he started working on the piece. The Arensbergs helped pay for it.

The artwork partly looks back at Duchamp's earlier works. It includes parts that look like his paintings Bride (1912), Chocolate Grinder (1914), and Glider containing a water mill in neighboring metals (1913–1915). This has led to many different ways of understanding the artwork. Duchamp officially said the work was "Unfinished" in 1923. When it was shipped back from its first public show, the glass cracked a lot. Duchamp fixed the big cracks but left the smaller ones. He accepted these accidental cracks as part of the artwork.

Until 1969, when the Philadelphia Museum of Art showed Duchamp's Étant donnés, people thought The Large Glass was his last major work.

Marcel Duchamp: Kinetic Art and Movement

Duchamp's interest in kinetic art (art that moves) can be seen early on. It shows up in his notes for The Large Glass and in his Bicycle Wheel readymade. Even though he lost interest in "retinal art" (art just for the eyes), he still liked visual tricks. In 1920, with help from Man Ray, Duchamp built a motorized sculpture. It was called Rotary Glass Plates, Precision Optics. Duchamp didn't think of it as art. It had a motor that spun rectangular glass pieces with parts of circles painted on them. When it spun, the circles looked like they were complete and moving. Man Ray tried to photograph it, but a belt broke, and a piece of glass shattered.

After moving back to Paris in 1923, Duchamp built another optical device. This was at the urging of André Breton and paid for by Jacques Doucet. This new device was called Rotary Demisphere, Precision Optics. This time, the spinning part was a globe cut in half with black circles painted on it. When it spun, the circles seemed to move forward and backward in space. Duchamp asked Doucet not to show it as art.

Rotoreliefs were Duchamp's next spinning artworks. To make these optical "play toys," he painted designs on flat cardboard circles. He spun them on a record player. When spinning, the flat disks looked three-dimensional. He had 500 sets of six designs printed. He set up a booth at a 1935 Paris inventors' show to sell them. It was a financial failure. However, some scientists thought they could help people who had lost vision in one eye see in 3D again. Duchamp, Man Ray, and Marc Allégret filmed early versions of the Rotoreliefs. They named the film Anémic Cinéma (1926). Later, in 1931, Duchamp visited Alexander Calder's studio. Looking at Calder's moving sculptures, Duchamp suggested they be called mobiles. Calder agreed, and that's what these types of sculptures are still called today.

Marcel Duchamp: Musical Ideas

Between 1912 and 1915, Duchamp explored different musical ideas. At least three pieces survived: two musical compositions and a note for a musical event. The two compositions were based on chance. Erratum Musical, written for three voices, was published in 1934. La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires même. Erratum Musical was never finished or published during Duchamp's life. The notes said it was for a mechanical instrument that would remove the need for a human musician. It also described a machine that would automatically record musical parts. These ideas came before John Cage's Music of Changes (1951), which is often seen as the first modern piece made mostly by chance.

In 1968, Duchamp and John Cage played chess together at a concert called "Reunion." As they played, they created Aleatoric music. This happened by triggering photoelectric cells placed under the chessboard.

Marcel Duchamp: Rrose Sélavy, His Other Self

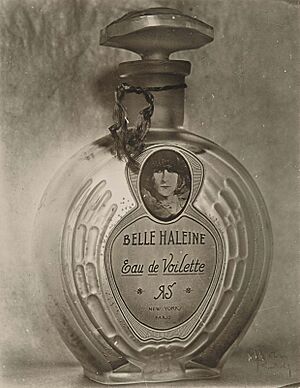

"Rrose Sélavy" was one of Duchamp's fake names. The name is a pun, sounding like the French phrase Eros, c'est la vie. This means "Eros, such is life." It can also sound like arroser la vie ("to make a toast to life"). Sélavy first appeared in 1921 in photos by Man Ray. These photos showed Duchamp dressed as a woman. Throughout the 1920s, Man Ray and Duchamp made more photos of Sélavy together. Duchamp later used this name to sign his writings and some artworks.

Duchamp used the name in the title of at least one sculpture, Why Not Sneeze Rose Sélavy? (1921). This sculpture is an assemblage, a type of readymade. It has a thermometer, small marble cubes that look like sugar, and a cuttlefish bone inside a birdcage. Sélavy's name also appears on the label of Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette (1921). This readymade is a perfume bottle in its original box. Duchamp also signed his film Anémic Cinéma (1926) with the Sélavy name.

The name Rrose Sélavy might have been inspired by Belle da Costa Greene. She was the librarian for J. P. Morgan at The Morgan Library & Museum. After Morgan's death, she became the library's director. She worked there for 43 years, buying and selling rare books and art.

Rrose Sélavy and Duchamp's other fake names might show his thoughts on artists. He believed that the idea of an artist being a unique, special person was not always true. Duchamp said in an interview, "You think you're doing something entirely your own, and a year later you look at it and you see actually the roots of where your art comes from without your knowing it at all."

From 1922, the name Rrose Sélavy also appeared in a series of clever sayings and wordplays by the French surrealist poet Robert Desnos. Desnos tried to make Rrose Sélavy seem like a long-lost royal queen of France. One saying honored Marcel Duchamp: Rrose Sélavy connaît bien le marchand du sel. In English, this means "Rrose Sélavy knows the merchant of salt well." In French, the last words sound like Mar-champ Du-cel. This is a phonetic anagram of the artist's name. Duchamp's collected notes are even called "Salt Seller." In 1939, a collection of these sayings was published under the name Rrose Sélavy.

Marcel Duchamp: From Art to Chess

In 1918, Duchamp left the New York art scene. He stopped working on the Large Glass and went to Buenos Aires. He stayed there for nine months and played a lot of chess. He even carved his own chess set from wood, with help from a local craftsman. He moved to Paris in 1919, then back to the United States in 1920. When he returned to Paris in 1923, Duchamp mostly stopped being a working artist. Instead, his main interest became chess. He studied it for the rest of his life, focusing on it more than almost anything else.

Duchamp is seen briefly playing chess with Man Ray in the short film Entr'acte (1924) by René Clair. He designed the poster for the 1925 Third French Chess Championship. He also played in the event, finishing with a score of 3 wins, 3 losses, and 2 draws. This earned him the title of chess master. During this time, his love for chess bothered his first wife so much that she glued his chess pieces to the chessboard. Duchamp continued to play in the French Championships and in the Chess Olympiads from 1928 to 1933. He preferred modern chess openings.

Around the early 1930s, Duchamp was at his best in chess. But he realized he probably wouldn't become a top-level player. In the years that followed, he played in fewer tournaments. Instead, he discovered correspondence chess (playing by mail) and became a chess journalist. He wrote weekly newspaper columns. While other artists were becoming very successful selling their works, Duchamp said, "I am still a victim of chess. It has all the beauty of art—and much more. It cannot be bought and sold. Chess is much purer than art in its social position." He also said, "The chess pieces are the block alphabet which shapes thoughts; and these thoughts, although making a visual design on the chess-board, express their beauty abstractly, like a poem. ... I have come to the personal conclusion that while all artists are not chess players, all chess players are artists."

In 1932, Duchamp worked with chess expert Vitaly Halberstadt. They published a book called L'opposition et cases conjuguées sont réconciliées (Opposition and Sister Squares are Reconciled). This book describes a very rare type of chess position that can happen at the end of a game. Using special diagrams, the authors showed that in this position, the best Black can hope for is a draw.

The idea of an "endgame" is important to understanding Duchamp's feelings about his art career. The Irish writer Samuel Beckett was a friend of Duchamp. He used the "endgame" idea in his 1957 play of the same name. In 1968, Duchamp played an important chess match with composer John Cage. Music was made by sensors under the chessboard, triggered by the game.

About choosing a chess career, Duchamp said, "If Bobby Fischer came to me for advice, I certainly would not discourage him... but I would try to make it positively clear that he will never have any money from chess, live a monk-like existence and know more rejection than any artist ever has, struggling to be known and accepted."

Duchamp left a special chess puzzle behind. He created an enigmatic endgame problem in 1943. It was included in an art exhibition announcement. The puzzle was printed on clear paper with the words: "White to play and win." Chess grandmasters and experts have tried to solve it, but most believe there is no solution.

Marcel Duchamp: Later Art Activities

Even though Duchamp was not seen as an active artist, he continued to advise artists, art dealers, and collectors. From 1925, he often traveled between France and the United States. In 1942, he made New York's Greenwich Village his home. He also worked on art projects sometimes. These included the short film Anémic Cinéma (1926), Box in a Valise (1935–1941), Self Portrait in Profile (1958), and the larger work Étant Donnés (1946–1966). In 1943, he worked with Maya Deren on her unfinished film The Witch's Cradle.

From the mid-1930s, he worked with the Surrealists. However, he never officially joined the movement, even though André Breton tried to convince him. From then until 1944, Duchamp helped edit the Surrealist magazine VVV with Max Ernst and others. He also advised for the magazine View, which featured him in 1945. This helped introduce him to more American people.

Duchamp's influence on the art world was mostly hidden until the late 1950s. Then, young artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns "discovered" him. They wanted to move away from the popular style called Abstract Expressionism. In 1960, he helped start the international writing group Oulipo. Interest in Duchamp grew again in the 1960s, and he became known worldwide. In 1963, the Pasadena Art Museum held his first major show. There, he was famously photographed playing chess against model Eve Babitz. This photo is considered a key image of modern American art.

The Tate Gallery in London held a big show of his work in 1966. Other major museums, like the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, also showed his work. He was asked to give talks about art and take part in discussions. He also gave interviews to major magazines. As the last living member of the Duchamp artist family, he helped organize a family art show in Rouen, France, in 1967. Parts of this show were later shown in Paris.

Marcel Duchamp: Exhibition Design and Installation Art

Duchamp helped design the 1938 Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme in Paris. This show was organized by André Breton and Paul Éluard. It had "Two hundred and twenty-nine artworks by sixty exhibitors from fourteen countries." The Surrealists wanted the exhibition itself to be a creative act. Marcel Duchamp was called "Generateur-arbitre" (generator-referee). Salvador Dalí and Max Ernst were technical directors. Man Ray was the lighting expert, and Wolfgang Paalen was in charge of "water and foliage."

One part of the lobby was filled with mannequins dressed by different Surrealists. The main hall, called the Salle de Superstition (Room of Superstition), was like a cave. It famously included Duchamp's installation, Twelve Hundred Coal Bags Suspended from the Ceiling over a Stove. This was literally 1,200 stuffed coal bags hanging from the ceiling. The floor was covered with dead leaves and mud. In the middle of the hall, under Duchamp's coal sacks, Paalen made an artificial pond with real water lilies. A single light bulb provided the only light. Visitors were given flashlights to see the art. The smell of roasting coffee filled the air. Around midnight, a lightly dressed girl suddenly appeared from the reeds. She jumped on a bed, screamed, and then disappeared. The Surrealists were happy that the show shocked many guests.

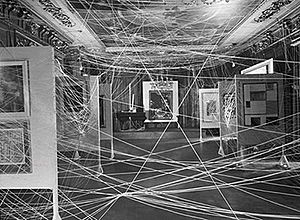

In 1942, the Surrealists asked Duchamp to design their "First Papers of Surrealism" show in New York. He created an installation called His Twine, also known as the "mile of string." It was a huge web of string throughout the rooms. In some places, it made it almost impossible to see the artworks. Duchamp secretly arranged for a friend's son to bring young friends to the opening. When the formally dressed guests arrived, they found a dozen children in sports clothes playing with balls and jumping rope. When asked, the children were told to say, "Mr. Duchamp told us we could play here." Duchamp's design for the show's catalog used "found" photos of the artists, not posed ones.

After the war, Breton and Duchamp organized the exhibition "Le surréalisme en 1947" in Paris. They named set designer Frederick Kiesler as the architect.

Marcel Duchamp: Étant donnés

Duchamp's last major artwork surprised the art world. People thought he had stopped making art for chess 25 years earlier. The artwork is called Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau / 2° le gaz d'éclairage ("Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas"). It is a scene that can only be seen through a small hole in a wooden door. Duchamp worked on this piece secretly from 1946 to 1966 in his Greenwich Village studio. Even his closest friends thought he had given up art.

Marcel Duchamp: Personal Life

Duchamp loved smoking cigars throughout his adult life. He became a citizen of the United States in 1955.

In June 1927, Duchamp married Lydie Sarazin-Lavassor. However, they divorced six months later. It was said that Duchamp married her for convenience, as she was the daughter of a rich car maker. In early 1928, Duchamp said he could no longer handle the responsibilities of marriage, and they soon divorced.

Between 1946 and 1951, Maria Martins was his partner. In 1954, he married Alexina "Teeny" Sattler. They stayed together until he died. Duchamp did not believe in God.

Marcel Duchamp: Death and Burial

Duchamp died suddenly and peacefully on 2 October 1968, at his home in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France. After having dinner with his friends Man Ray and Robert Lebel, Duchamp went to bed. He collapsed in his studio and died of heart failure.

He is buried in the Rouen Cemetery in Rouen, France. His gravestone has the words, "D'ailleurs, c'est toujours les autres qui meurent" ("Besides, it's always the others who die").

Marcel Duchamp: His Legacy in Art

Many art experts believe Duchamp is one of the most important artists of the 20th century. His work influenced the development of Western art after World War I. He advised modern art collectors, like Peggy Guggenheim. This helped shape art tastes during that time. He challenged traditional ideas about how art is made. He also pushed back against the growing art market. He famously called a urinal art and named it Fountain. Duchamp made relatively few artworks. He mostly stayed away from the popular art groups of his time. He even pretended to stop making art and focus on chess, while secretly continuing to create.

Duchamp's influence on the art world was mostly hidden until the late 1950s. Then, young artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns discovered him. They wanted to move away from the popular style called Abstract Expressionism. In 2004, a group of famous artists and art historians voted Fountain "the most influential artwork of the 20th century."

The Prix Marcel Duchamp (Marcel Duchamp Prize), started in 2000, is an award given each year to a young artist by the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Marcel Duchamp: Selected Works

See also

In Spanish: Marcel Duchamp para niños

In Spanish: Marcel Duchamp para niños