John Cage facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Cage

|

|

|---|---|

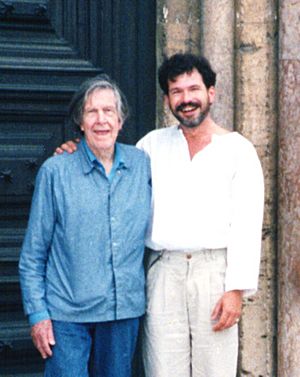

Cage in 1988

|

|

| Born |

John Milton Cage Jr.

September 5, 1912 Los Angeles, California, U.S.

|

| Died | August 12, 1992 (aged 79) New York City, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | Pomona College |

| Occupation |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Xenia Andreyevna Kashevaroff

(m. 1935; div. 1945) |

| Partner(s) | Merce Cunningham |

| Signature | |

|

|

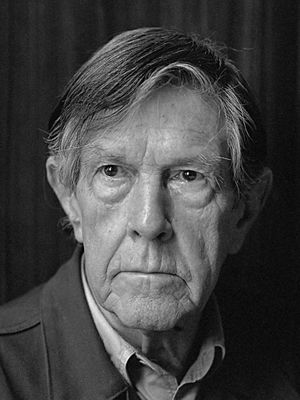

John Milton Cage Jr. (born September 5, 1912 – died August 12, 1992) was an American composer and music thinker. He was a leader in new music ideas after World War II. He explored music where parts were left to chance, used electronic sounds, and found new ways to play musical instruments. Many people see him as one of the most important composers of the 20th century. He also helped shape modern dance, working closely with dancer Merce Cunningham, who was his close friend and artistic partner for many years.

One of Cage's most famous pieces is 4′33″ from 1952. In this work, musicians do not play any planned sounds. Instead, the audience listens to the sounds of the environment around them for four minutes and thirty-three seconds. This piece made people think differently about what music and performance could be. Cage also invented the prepared piano. This is a piano whose sound is changed by placing objects like screws or rubber between or on its strings. He wrote many pieces for this instrument, including Sonatas and Interludes (1946–48).

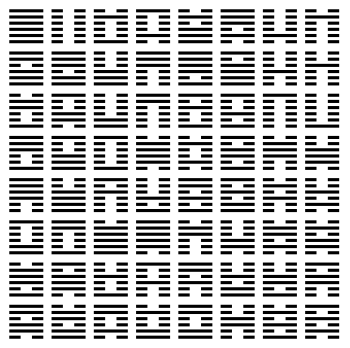

Cage learned from famous composers like Henry Cowell and Arnold Schoenberg. However, his biggest inspirations came from East and South Asian cultures. After studying Indian philosophy and Zen Buddhism in the late 1940s, Cage started using chance in his music. He began composing this way in 1951. The I Ching, an ancient Chinese classic text that uses chance to give advice, became his main tool for creating music. In a 1957 talk, he described music as "a purposeless play." He said it was "an affirmation of life" and "simply a way of waking up to the very life we're living."

John Cage's Life Story

Growing Up (1912–1931)

John Cage was born on September 5, 1912, in Los Angeles, California. His father, John Milton Cage Sr., was an inventor. His mother, Lucretia Harvey, worked as a journalist for the Los Angeles Times. John's father taught him that if someone says "can't," it shows you what to do. This idea likely influenced Cage's later experimental work.

Cage started piano lessons in fourth grade. He enjoyed reading music more than becoming a skilled player. At first, he didn't plan to become a composer. In high school, he gave a speech at the Hollywood Bowl suggesting a day of quiet for all Americans. He believed that being "hushed and silent" would help people hear what others think. This idea was similar to his later famous piece, 4′33″.

In 1928, Cage went to Pomona College to study theology. There, he learned about the works of artist Marcel Duchamp and writer James Joyce. He also discovered the ideas of philosopher Ananda Coomaraswamy and composer Henry Cowell.

Cage later convinced his parents that traveling in Europe would be better for a future writer than college. He traveled for about 18 months, trying different art forms. He studied architecture, then painting, poetry, and music. In Europe, he heard modern composers like Igor Stravinsky and Paul Hindemith for the first time. He also discovered the music of Johann Sebastian Bach. He started composing his first pieces in Majorca, Spain. These early works used complex math, but he wasn't happy with them.

Learning to Compose (1931–1936)

When Cage returned to the United States in 1931, he gave talks on modern art. He met important artists like Richard Buhlig, who became his first composition teacher. By 1933, Cage decided to focus on music. He sent some of his music to Henry Cowell, who suggested he study with Arnold Schoenberg. Schoenberg was a famous composer known for his new ideas.

Cage moved to New York City in 1933 and studied with Cowell and Adolph Weiss. He worked hard, often sleeping only four hours a night and composing for four hours every day. Later that year, he began studying with Schoenberg in California. Schoenberg was a big influence on Cage. Cage admired him greatly and promised to dedicate his life to music.

After two years, Cage decided to leave Schoenberg's classes. Schoenberg had told his students that he was trying to make it impossible for them to write music. Cage felt this was a challenge and decided to write music more than ever. Schoenberg later called Cage an "inventor—of genius" rather than a composer. Cage liked this idea and often said he was an inventor, not a composer.

Around 1934–35, Cage met artist Xenia Andreyevna Kashevaroff. She was from Alaska and worked with bookbinding, sculpture, and collage. Cage fell in love and they married on June 7, 1935.

New Sounds and Eastern Ideas (1937–1949)

After marrying, John and Xenia Cage moved to Hollywood. Cage took many jobs, including playing music for dance classes at the University of California, Los Angeles. This started his long connection with modern dance. He began experimenting with unusual instruments, like household items and metal sheets. He was inspired by artist Oskar Fischinger, who said that "everything in the world has a spirit that can be released through its sound."

In 1938, Cage moved to San Francisco and then to Seattle. He worked at the Cornish College of the Arts as a composer and accompanist for dancer Bonnie Bird. He formed a percussion group that toured the West Coast, bringing him his first fame. In 1940, he invented the prepared piano. This allowed him to create new sounds from a piano by placing objects between its strings. At Cornish, he met dancer Merce Cunningham, who became his lifelong artistic partner.

In 1942, Cage moved to New York City. He met famous artists like Marcel Duchamp. He struggled financially but continued to compose for prepared piano. His marriage ended in 1945, and Cunningham became his partner. Cage also wrote The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs (1942) for voice and a closed piano, which became popular.

By the mid-1940s, Cage felt unsure about music as a way to communicate. In 1946, he began studying Indian music and philosophy with Gita Sarabhai. He also attended lectures on Zen Buddhism. These studies led him to believe that music's purpose was "to sober and quiet the mind." This new way of thinking influenced works like Sonatas and Interludes for prepared piano and String Quartet in Four Parts.

Discovering Chance (1950s)

After a concert in 1949, Cage received a grant that allowed him to travel to Europe. In 1950, he met composer Morton Feldman in New York City. They became good friends, and Cage, Feldman, Earle Brown, David Tudor, and Christian Wolff became known as "the New York school" of composers.

In 1951, Christian Wolff gave Cage a copy of the I Ching. This ancient Chinese book uses chance to help people make decisions. Cage started using the I Ching to compose music. He would ask the book questions, and the answers would guide his musical choices. This meant "imitating nature in its manner of operation."

This new approach led to works like Imaginary Landscape No. 4 for 12 radio receivers and Music of Changes for piano. The I Ching became Cage's main tool for composing after 1951. He even used a computer program later to create numbers like the I Ching coin tosses.

In 1952, Cage created his most famous and talked-about piece: 4′33″. The score tells the performer not to play their instrument. The music is meant to be the sounds of the environment that listeners hear. The first performance caused a big reaction. Many people did not understand or like Cage's use of chance. Some critics and other composers stopped supporting his work.

Despite these challenges, Cage continued to teach. He taught at the Black Mountain College in 1948, 1952, and 1953. In 1952, he organized what is called the first "happening" in the United States. This was a multi-media performance event that greatly influenced art in the 1950s and 60s.

From 1953, Cage focused on composing for modern dance, especially for Merce Cunningham. He also developed new ways to use chance in his music. In 1954, he moved to a community called Gate Hill Cooperative. His financial situation slowly improved. From 1956 to 1961, he taught experimental composition classes. He also worked as an art director. Important works from this time include Concert for Piano and Orchestra (1957–58), which used graphic symbols instead of traditional notes.

Gaining Fame (1960s)

In the 1960s, John Cage became more widely known. In 1961, Wesleyan University Press published Silence, a collection of his lectures and writings. This book became very popular and influential. It included his famous Lecture on Nothing, which was structured like some of his music.

Cage also began working with Edition Peters, a music publisher. They published many of his scores, which helped him gain more recognition. By the mid-1960s, Cage was very busy with commissions and performances. This meant he composed less music during this time. After Atlas Eclipticalis (1961–62), an orchestral piece based on star charts, Cage started creating "music (not composition)." This meant his scores gave instructions rather than exact notes.

Many of his pieces from the 1960s were "happenings." These were art events created by Cage and his students. Happenings were theatrical events that broke away from traditional stages and audiences. They often had no plot and were left to chance. Cage believed that theater was the best way to combine art and real life. The term "happenings" was created by his student Allan Kaprow.

In 1967, Cage's book A Year from Monday was published. His parents passed away during this decade. Cage had their ashes scattered in the Ramapo Mountains in New York, and he asked for the same to be done for him.

New Directions (1969–1987)

In the 1960s, Cage created some of his largest and most ambitious works. These reflected the ideas of the time and his interest in new media and technology. HPSCHD (1969), made with Lejaren Hiller, was a huge multimedia piece. It involved seven harpsichords, computer-generated sounds, slides, and films. The audience could walk around freely during the five-hour performance.

Also in 1969, Cage wrote Cheap Imitation for piano. This piece was a chance-controlled version of Erik Satie's Socrate. It was unusual for Cage because it sounded very personal and showed his affection for Satie's music. This piece marked a change in Cage's music. He started writing more fully notated works for traditional instruments again. He also began to use improvisation in pieces like Child of Tree (1975).

Cheap Imitation was the last piece Cage performed in public himself. He had Arthritis since 1960, and by the 1970s, his hands were too painful to play. He continued to write books of prose and poetry, including M (1973) and Empty Words (1979). From 1978 until his death, Cage also created many prints and watercolors.

Final Years (1987–1992)

In 1987, Cage started a new series of works called Number Pieces. These pieces were for different numbers of performers. For example, Two was for flute and piano. The music had short written parts to be played at any speed within certain time limits. He wrote about forty of these pieces. The way he composed them, using chance to select pitches, was linked to his ideas about freedom. One11 (1992) was his only film, showing chance-determined patterns of electric light.

He also created five operas, all called Europera, between 1987 and 1991. Some were large, and others were for smaller groups.

Cage's health got worse in the 1980s. He had arthritis, nerve pain, and hardening of the arteries. He also had a stroke and broke an arm. Despite this, he continued to create art. On August 11, 1992, he had another stroke and died the next morning at age 79.

Following his wishes, Cage was cremated, and his ashes were scattered in the Ramapo Mountains in New York, where his parents' ashes were also scattered.

John Cage's Music

Early Works and Rhythmic Ideas

Cage's first pieces are now lost. He said they were short piano pieces made with complex math, but they didn't sound very emotional. He then tried improvising and writing down the music. His teacher, Richard Buhlig, taught him the importance of structure. Many of his early works, like Sonata for Clarinet (1933), used many different notes and showed his interest in counterpoint (combining different melodies).

When Cage started writing music for percussion and modern dance, he focused on rhythmic structure. In Imaginary Landscape No. 1 (1939), he used sections of different lengths (16, 17, 18, and 19 bars). Each section was also divided into smaller parts. First Construction (in Metal) (1939) used a similar idea with "nested proportions." This became a common feature in his music throughout the 1940s, making pieces like Sonatas and Interludes very complex.

In the late 1940s, Cage found new ways to move away from traditional harmony. For example, in String Quartet in Four Parts (1950), he created "gamuts," which were chords with specific instruments. The piece moved from one gamut to another. The choice of gamut was based only on whether it had the right note for the melody, so the other notes didn't follow traditional harmony rules. The last part of his Concerto for prepared piano (1950–51) began to use chance, which he soon fully adopted.

Music of Chance

Cage used a chart system for his piano work Music of Changes (1951). But here, he used the I Ching to choose material from the charts. After 1951, almost all of Cage's music was composed using chance. For example, in Music for Piano, he used imperfections on paper to find pitches. He used coin tosses and I Ching numbers to decide other musical details. He created a series of works by applying chance to star charts, like Atlas Eclipticalis (1961–62) and his difficult etudes: Etudes Australes (1974–75), Freeman Etudes (1977–90), and Etudes Boreales (1978). These etudes were very hard to play. Cage believed this difficulty showed that "the impossible is not impossible," reflecting his social and political views. He saw himself as an anarchist and was influenced by Henry David Thoreau.

Another group of works used chance with existing music by other composers. These included Cheap Imitation (1969, based on Erik Satie) and Some of "The Harmony of Maine" (1978). In these pieces, Cage kept the original rhythm but used chance to choose new pitches. The Number Pieces, written in his last five years, used "time brackets." The score had short musical parts with instructions on when to start and end them (e.g., play anytime between 1 minute 15 seconds and 1 minute 45 seconds).

Cage's way of using the I Ching was complex, not just simple random choices. The exact steps changed for each piece. For Cheap Imitation, he asked the I Ching specific questions about musical scales and notes. For Etudes Australes, he used star charts to find pitches. Then he asked the I Ching which pitches should be single notes and which should be part of chords.

Some of Cage's works, especially from the 1960s, gave instructions to the performer instead of fully written music. Variations I (1958) gave the performer clear plastic squares with points and lines. The performer would combine the squares and use the lines and points like a graph to decide how to play sounds. Other works from this time were just text instructions. 0′00″ (1962), also known as 4′33″ No. 2, simply said: "In a situation provided with maximum amplification, perform a disciplined action."

Musicircus (1967) invited performers to gather and play together. The first Musicircus had many performers and groups in a large space. They were told when to start and stop playing, and when to play alone or in groups. This created a mix of many different sounds, all determined by chance. Many Musicircuses have been held since then.

This idea of a "circus" was important to Cage. It appeared in pieces like Roaratorio, an Irish circus on Finnegans Wake (1979). This piece used sounds and recordings from Ireland, based on James Joyce's novel Finnegans Wake, which was one of Cage's favorite books.

Using Improvisation

Cage generally didn't like improvisation because it involved the performer's personal choices, which he tried to avoid with chance. However, in some works from the 1970s, he found ways to include it. In Child of Tree (1975) and Branches (1976), performers were asked to use certain plants as instruments, like an amplified cactus. The structure and sounds of the pieces were determined by the chance choices of the performers. In Inlets (1977), performers played large water-filled conch shells. They would tip the shells to make bubbles, which produced sound. Since it was impossible to know when a bubble would form, the performance was guided by pure chance.

Other Creative Work

Visual Art and Writings

John Cage started painting when he was young but stopped to focus on music. His first major visual art project, Not Wanting to Say Anything About Marcel, was from 1969. It included lithographs and plexigrams (silk screen prints on plastic panels). These works used words in different fonts, all arranged by chance.

From 1978 until his death, Cage worked at Crown Point Press, making new prints every year. His first project there was Score Without Parts (1978), based on drawings by Henry David Thoreau. He also made Seven Day Diary, which he drew with his eyes closed but followed a strict structure based on chance.

Between 1979 and 1982, Cage created large series of prints. Later, he started using unusual materials like cotton, foam, stones, and fire in his art. In 1988–1990, he made watercolors.

The only film Cage made was One11, part of his Number Pieces series. It was a 90-minute black-and-white film showing only chance-determined patterns of electric light. It was finished just weeks before he died in 1992.

Throughout his life, Cage also gave many lectures and wrote books. His first book, Silence: Lectures and Writings (1961), included not only lectures but also experimental texts like Lecture on Nothing. His later books also featured different types of content, from music lectures to poetry.

Cage was also very interested in mushrooms. He helped start the New York Mycological Society. His collection of mushrooms is now kept at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Archives

- The John Cage Trust archive is at Bard College in New York.

- The John Cage Music Manuscript Collection at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts has most of his musical writings.

- The John Cage Papers at Wesleyan University's Olin Library contain his writings, interviews, and other items.

- The John Cage Collection at Northwestern University in Illinois has his letters and the Notations collection.

See also

In Spanish: John Cage para niños

In Spanish: John Cage para niños

- An Anthology of Chance Operations

- List of compositions by John Cage

- The Organ2/ASLSP (a.k.a. As Slow as Possible) project, one of the longest concerts ever.

- The Revenge of the Dead Indians, a 1993 film about Cage.

- Works for prepared piano by John Cage

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |