Henry Cowell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henry Cowell

|

|

|---|---|

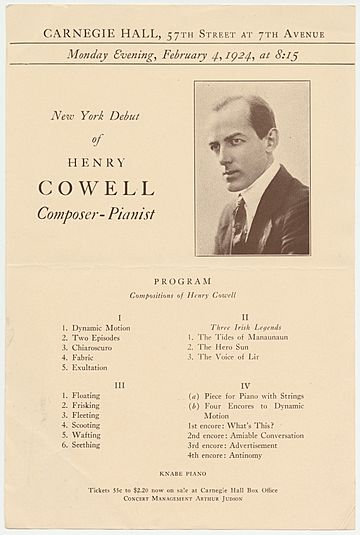

Photo from promotional flier for Cowell's 1924 Carnegie Hall debut

|

|

| Born | March 11, 1897 Menlo Park, California, U.S.

|

| Died | December 10, 1965 (aged 68) Woodstock, New York, U.S.

|

| Occupation | |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Parent(s) | Harry Cowell Clarissa Dixon |

| Signature | |

Henry Dixon Cowell (born March 11, 1897 – died December 10, 1965) was an American composer, writer, pianist, publisher, and teacher. He was married to Sidney Robertson Cowell. Henry Cowell became a very important person in American modern music during the first half of the 1900s. His music and writings greatly influenced other artists like Lou Harrison, George Antheil, and John Cage. Many people consider him one of America's most important and influential composers.

Cowell mostly taught himself music. He created a very special musical style. This style often mixed American folk music with unusual sounds and instruments. He also used ideas from Irish legends. He was one of the first to use many new ways of composing music, especially for the piano. These included playing the string piano (touching the strings inside), using a prepared piano (placing objects on strings), and creating tone clusters (playing many notes at once). He also used graphic notation, which uses pictures instead of traditional notes.

Contents

Henry Cowell's Early Life

Growing Up as Henry Cowell

Henry Cowell was born on March 11, 1897, in a quiet area of Menlo Park, California. This town is near San Francisco. His father, Harry Cowell, was a poet from County Clare, Ireland. His mother, Clarissa Cowell, was a writer and liked to speak up for what she believed in. She was from the American Plains.

Henry heard music from a very young age. His parents often sang him folk songs from their home countries. He could sing these songs before he could even speak. When they visited San Francisco, he heard music from Indonesia, China, and Japan. Friends gave the family small instruments, like a mandolin harp and a tiny violin. Young Henry loved the violin and played it for a few years.

When Henry was five, his parents separated. He then lived with his mother in Chinatown. Here, he learned about different cultures and music from his new Asian-American friends. After the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake, their home was destroyed. Henry and his mother had to leave California. They lived with family and friends in different states, including Iowa and New York City. Teachers noticed Henry's amazing musical talent.

His mother became very ill. When they returned to San Francisco, their home was ruined. Henry, who was thirteen, worked hard to fix it. He took small jobs like selling flowers, cleaning, and farming to help them financially.

Learning Music and Starting Out

Henry did not have much formal music education. His mother taught him at home. But in his mid-teens, he started writing short classical pieces. He saved money from his jobs and bought a used upright piano when he was fifteen. This piano helped him write a lot more music. By 1914, he had written over 100 pieces. He began to experiment by hitting the keyboard hard or rolling objects across the strings inside the piano.

At age 17, Cowell went to the University of California, Berkeley. He studied composition with Charles Seeger, a famous American music expert. Seeger encouraged Cowell to write about his new ways of using tone clusters. This later became his book, New Musical Resources.

Still a teenager, Cowell wrote Dynamic Motion (1916). This was an important piece that explored tone clusters. To play it, the musician uses their forearms to play many notes at once. After two years at Berkeley, Seeger suggested Cowell study in New York City. Cowell only stayed there for three months. He felt the music scene was too strict. But in New York, he met another modern piano composer, Leo Ornstein. They worked together later on.

In February 1917, Cowell joined the army. He served in an ambulance training facility during World War I. He was an assistant band director for a few months.

Time at Halcyon

Cowell later returned to California. He became involved with Halcyon, a spiritual community. He joined after meeting John Varian, an Irish-American poet. Cowell loved Irish folk music because of his father. He was drawn to Irish nationalism, Celtic legends, and the community's spiritual ideas.

The people at Halcyon had traditional music tastes. But Cowell convinced them to try his music. He wrote music for their plays. In 1917, he wrote music for Varian's play The Building of Banba. The prelude he composed, The Tides of Manaunaun, became his most famous work. It used rich, strong tone clusters. Irish symbols became a big part of his music.

Henry Cowell's Musical Journey

New Music and Early Concerts

In the early 1920s, Cowell traveled widely in North America and Europe. He performed his own experimental music as a pianist. This music explored new ideas like atonality (music without a main key), polytonality (using many keys at once), and polyrhythms (many rhythms at once). He was the first American musician to visit the Soviet Union. Many of his concerts caused big reactions and even protests.

In 1923, in Berlin, he met pianist Grete Sultan. They worked closely together. Cowell's tone cluster technique was so impressive that famous European composers Béla Bartók and Alban Berg asked his permission to use it.

Cowell also developed a new method called "string piano". Instead of playing the keys, the pianist reaches inside the piano. They pluck, sweep, or touch the strings directly. This method inspired John Cage to create the prepared piano. In his early chamber music, Cowell used a method he called "rhythm-harmony." Each musical part had its own rhythm.

In 1919, Cowell started writing New Musical Resources. This book was published in 1930. In it, he explained his new ideas about rhythm and harmony. He talked about how musical sounds are related to the harmonic series. This book had a huge impact on American experimental music for many years. John Cage even copied the book by hand.

The Leipzig Concert

During his first tour in Europe, Cowell played at the famous Gewandhaus concert hall in Leipzig, Germany, on October 15, 1923. The audience reacted very strongly to this concert. As he played his loudest and most daring pieces, the audience became more and more upset.

One man jumped up and shook his fist at Cowell. Others threw programs at him. Soon, an angry group of audience members climbed onto the stage. A second group, who supported Cowell, followed them. The two groups started shouting and fighting. The police were called. Cowell later remembered, "The police came onto the stage and arrested 20 young fellows, the audience being in an absolute state of hysteria — and I was still playing!" He was not hurt, but he was very shaken after the concert.

Newspapers in Leipzig were very critical of Cowell and his music. This event was compared to other wild concerts by experimental composers in Europe, like the premiere of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring.

More Experiments in Music

Cowell was very interested in how rhythms and harmonies work together. In 1930, he asked Léon Theremin to create the Rhythmicon. This was a special keyboard instrument. It could play notes in rhythms that matched the overtone series of a chosen musical note. It was the world's first electronic rhythm machine. It could play up to sixteen different rhythms at the same time. Cowell wrote several pieces for this instrument. However, the Rhythmicon was mostly forgotten until the 1960s.

Cowell continued to create very new music until the mid-1930s. His solo piano pieces were very important during this time. These included The Banshee (1925), which required playing the piano strings directly. Another was the wild, cluster-filled Tiger (1930), inspired by William Blake's famous poem. Critics often praised Cowell's unique piano techniques.

He also wrote many songs, over 180 in his career. He adapted his piece Aeolian Harp to go with a poem by his father. He wrote chamber music, like the Adagio for Cello and Thunder Stick (1924), which used unusual instruments. His Ostinato Pianissimo (1934) made him a leader in writing for percussion groups. He also wrote powerful pieces for large groups, like the Concerto for Piano and Orchestra (1928). In the early 1930s, Cowell started using aleatoric procedures. This meant performers could decide some parts of the music themselves. For example, his Mosaic Quartet (1935) has five movements that can be played in any order.

New Music Society and Helping Other Artists

Cowell was a central figure among a group of modern composers. This group included his friends Carl Ruggles and Dane Rudhyar, as well as Leo Ornstein and Ruth Crawford. In 1925, Cowell started the New Music Society. This group put on concerts of their own works and those of other artists like Arnold Schoenberg.

Less than two years later, Cowell founded a music magazine called New Music Quarterly. This magazine published many important new musical scores. It featured works by his group and other composers like Aaron Copland. Before the first issue, he asked for contributions from a little-known composer who became one of his closest friends, Charles Ives. Many of Ives's major works were first published in New Music. Ives also helped fund many of Cowell's projects.

In 1928, Cowell helped create the Pan-American Association of Composers. This group aimed to promote composers from all over North and South America. Their first concert in New York City in 1929 featured only Latin American music. Their next concert focused on American modern composers. Over the next four years, the association held concerts in New York, Europe, and Cuba.

Cowell also taught composition and music theory. Many famous musicians were his students, including George Gershwin, Lou Harrison, and John Cage. Cage called Cowell "the open sesame for new music in America."

Cowell was very open to different kinds of music. He grew up hearing "world music" from China, Japan, and Tahiti. This helped him develop his wide musical taste. He famously said, "I want to live in the whole world of music." He studied Indian classical music and gamelan (music from Indonesia). In the late 1920s, he taught a course called "Music of the World's Peoples." In 1931, he received a special grant to study comparative musicology in Berlin. This field is now called ethnomusicology, which is the study of music from different cultures.

Later Life and Music

A Change in Style

After a difficult period, Cowell's music changed. His new compositions became simpler in rhythm and more traditional in harmony. Many of his later works were based on American folk music. He wrote a series of eighteen Hymn and Fuguing Tunes (1943–64). While folk music was in his earlier works, the wild changes he used before were mostly gone.

Even though his style changed, Cowell continued to be a leader in bringing non-Western music into his compositions. Examples include the Japanese-inspired Ongaku (1957) and Symphony No. 13, "Madras" (1956–58). He also wrote some of his most touching songs during this time. In 1951, Cowell was elected to the American Institute of Arts and Letters.

He became friends with Charles Ives again. Cowell and his wife wrote the first major study of Ives's music. He also helped his former student, Lou Harrison, champion Ives's music. Cowell continued to teach. He also worked as a consultant for Folkways Records for over ten years. He wrote notes for albums like Music of the World's Peoples. In 1963, he recorded twenty of his important piano pieces for an album. In his final years, Cowell created new unique works, like Thesis (Symphony No. 15; 1960).

Final Years

In October 1964, Henry Cowell was diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Doctors found that the cancer was too advanced to be removed by surgery. Cowell died on December 10, 1965, at his home in Woodstock, New York. He passed away after suffering several strokes and from the disease.

Henry Cowell's Compositions

Henry Cowell's career lasted over fifty years. He wrote in many different styles, always adding his own special touch. These styles included serialism, jazz, romanticism, neoclassicism, avant-garde, noise music, and minimalism. He is believed to have written over 940 compositions in total. Most of these were for solo piano. Some of his works have been lost or destroyed. His large collection of music is usually divided into three periods: an early experimental period, a more technical middle period, and a later period with a more traditional sound.

Henry Cowell's Legacy

His Contributions to Music

Many of the musical techniques Henry Cowell invented or helped develop are still used today. Tone clusters have been used by famous classical composers like Béla Bartók, Olivier Messiaen, and Krzysztof Penderecki. Experimental and progressive rock keyboardists like Keith Emerson and John Cale also use string piano techniques and clusters. So do free jazz pianists like Sun Ra.

His 1930 book New Musical Resources is still a helpful guide for composers, even ninety years after it was published. His friends and students continued to support it.

Selected Discography

Recordings by Cowell

- Henry Cowell: Piano Music (Smithsonian Folkways 40801)—features twenty of his solo piano pieces, including Dynamic Motion, The Tides of Manaunaun, Aeolian Harp, The Banshee, and Tiger, plus a commentary track.

- Tales of Our Countryside (American Columbia 78rpm Set X 235, recorded July 5, 1941)—performed by the All-American Youth Orchestra led by Leopold Stokowski, with Cowell as the piano soloist.

Selected Recordings by Others

- American Piano Concertos: Henry Cowell (col legno 20064)—includes large-ensemble pieces like Concerto for Piano and Orchestra and Sinfonietta, as well as The Tides of Manaunaun and other solo piano pieces.

- The Bad Boys!: George Antheil, Henry Cowell, Leo Ornstein (hatHUT 6144)—features solo piano pieces, including Anger Dance, The Tides of Manaunaun, and Tiger.

- Dancing with Henry (mode 101)—includes solo and chamber pieces, performed by California Parallèle Ensemble.

- Henry Cowell (First Edition 0003)—features orchestral pieces, including Ongaku and Thesis (Symphony No. 15).

- Henry Cowell: A Continuum Portrait, Vol. 1 (Naxos 8.559192) and Vol. 2 (Naxos 8.559193)—includes solo, chamber, vocal, and large-ensemble pieces.

- Henry Cowell: Mosaic (mode 72/73)—features solo and chamber pieces, including Quartet Romantic, Quartet Euphometric, and Mosaic Quartet (String Quartet No. 3).

- Henry Cowell: Persian Set (Composers Recordings Inc. CRI-114 recorded April 1957 and reissued on Citadel CTD 88123)—Four movements for Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Leopold Stokowski.

- Henry Cowell: Persian Set (Koch 3-7220-2 HI)—includes orchestral and large-ensemble pieces, such as Hymn and Fuguing Tune No. 2.

- New Music: Piano Compositions by Henry Cowell (New Albion 103)—features solo piano pieces.

- Songs of Henry Cowell (Albany–Troy 240)—includes How Old Is Song?, Music I Heard, and Firelight and Lamp.

Images for kids

-

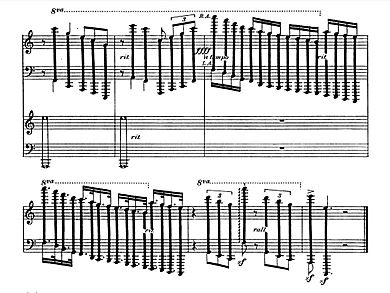

The finale of the movement Antinomy from Five Encores to Dynamic Motion (1917), showing five-and-a-half octave chromatic clusters to be played with both forearms

-

Satirical caricature of Cowell at the piano by American cartoonist and illustrator Harry Haenigsen, c. mid-1920s

See also

In Spanish: Henry Cowell para niños

In Spanish: Henry Cowell para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |