Lou Harrison facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lou Harrison

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait of a young Harrison at the piano, c. early 1940s

|

|

| Born | May 14, 1917 Portland, Oregon, U.S.

|

| Died | February 2, 2003 (aged 85) Lafayette, Indiana, U.S.

|

| Occupation | |

| Partner(s) |

|

| Signature | |

|

|

Lou Silver Harrison (born May 14, 1917 – died February 2, 2003) was an American composer, music critic, and music theorist. He was also a painter and created many unique musical instruments.

Lou Harrison first wrote music in a modern style, like his teacher Henry Cowell. But later, he started adding sounds and ideas from non-Western cultures. For example, he wrote many pieces for Javanese-style gamelan instruments. He learned about these after studying in Indonesia.

Harrison and his partner, William Colvig, even built their own musical instruments. They are known for helping start the American gamelan movement and world music in the U.S.

Most of Harrison's music and custom instruments use a special tuning called just intonation. This is different from the common "equal temperament" tuning. He was one of the first composers to use the international language Esperanto in his music. He also explored themes of personal identity in his works.

Contents

Early Life and Musical Journey

Childhood and Early Interests

Lou Harrison was born on May 14, 1917, in Portland, Oregon. His parents were Clarence and Calline Harrison. His family had some money at first, but they faced tough times during the Great Depression.

When Lou was nine, his family moved around Northern California. They lived in places like Sacramento and San Francisco. San Francisco had many Asian Americans, and Lou was often surrounded by Eastern influences.

His mother decorated their home with Japanese lanterns and Persian rugs. Lou loved the different kinds of music he heard there. This included Cantonese opera, Hawai'ian kīkākila, jazz, and classical music. He later said he heard more traditional Chinese music than European music growing up.

Lou's parents supported his early interest in music. His mother paid for piano lessons. His father drove him to study Gregorian chant for a short time. Because his family moved often, Lou didn't make many long-term friends. He often felt like an outsider.

He decided to follow his own artistic ideas. He spent a lot of time at the library, reading about everything from animals to Confucianism. This wide range of interests helped him connect different ideas in his music later on. It's thought that his lonely youth made him dislike big cities.

First Steps in Music Education

After high school in 1934, Harrison went to San Francisco State College. There, he took Henry Cowell's "Music of the Peoples of the World" class. Lou quickly became one of Cowell's best students.

In 1935, Harrison heard one of Cowell's pieces for piano and percussion. He called it one of the most amazing works he had ever heard. Later, Harrison used similar ideas in his own music. He used "found percussion" (like everyday objects) and "aleatoric" (chance-based) performances.

That same year, Harrison started private composition lessons with Cowell. They became close friends until Cowell's death in 1965. Cowell was the first to publish Harrison's music. When Cowell was in prison, Harrison publicly asked for his release. He also visited him regularly for lessons.

At 19, Harrison became a temporary professor of music at Mills College from 1936 to 1939. In 1941, he moved to the University of California, Los Angeles. He worked in the dance department, teaching and playing piano.

While there, he took lessons from Arnold Schoenberg. This made him more interested in the twelve-tone technique, a way of composing music. Harrison said it was easy to learn this technique after what Cowell taught him.

At this time, Harrison wrote many pieces for percussion. He used unusual items like old car brake drums and garbage cans as instruments. He also used "tone clusters" in his piano works. This meant playing many notes at once, often with a special wooden bar. This made the piano sound louder and more like a gong. His experimental style grew during this time. Pieces like his Concerto for Violin and Percussion Orchestra (1940) showed this.

This unique music caught the attention of John Cage, another student of Cowell's. Harrison and Cage later worked together.

Years in New York City

Harrison was often told to study music in Europe. But he always chose not to go. He wanted to support and promote other American composers. In 1943, Harrison moved to New York City. He worked as a music critic for the New York Herald Tribune.

In New York, he met many modern composers. He became good friends with Charles Ives. Harrison later worked hard to make Ives's music known to the world. Ives's works had often been ignored before. With help from his mentor Cowell, Harrison helped prepare and conduct the first performance of Ives's Symphony No. 3. Ives even gave Harrison half of his Pulitzer Prize for Music money for that piece.

Even though his creative work was going well, Harrison felt lonely and worried in the city. He missed the West Coast a lot. By 1945, he was struggling with his health due to stress. He tried to write new music, but he often tore it up. He felt very unsure about his compositions and how people saw him.

In May 1947, extreme stress from missing home and a busy work schedule led to a very difficult time for Harrison. John Cage helped him get to a clinic for recovery. Harrison stayed there for several weeks. He wrote to Cowell, expressing his deep sadness and worry about his career.

His recovery took nine months of treatment and several more years of checkups. Many thought this would end his career. But Harrison kept composing. While recovering, he wrote parts of his Symphony on G (1952) and often painted.

He decided he needed to return to California. In a 1948 letter, Harrison wrote, "I long to live simply and well and that just isn't possible here."

A New Life in California

Developing a New Musical Style

His difficult time in New York made Harrison rethink his music style. He decided to move away from the harsh sounds he used before. Instead, he chose a more flowing, melodic style. He used diatonic and pentatonic scales, which sound more traditional.

This made his music very different from the academic styles popular at the time. The two years after he left the hospital in 1949 were very productive. He created works like the Suite for Cello and Harp.

Following his friend Colin McPhee, who studied Indonesian music, Harrison's style began to sound more like gamelan music. He said, "It was the sound itself that attracted me." He tried to imitate the general sounds of gamelan in pieces like his Suite for Violin, Piano, and Small Orchestra (1951).

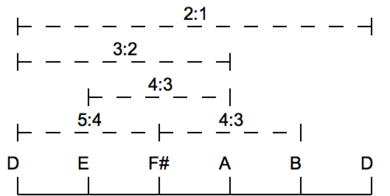

In the early 1950s, Harrison received a copy of Harry Partch's book on musical tuning, Genesis of a Music. This inspired him to stop using equal temperament. He started writing music in just intonation, which uses simple, pure sound ratios. He believed music was "emotional mathematics." He once said he wished musicians could understand these ratios as well as they read notes.

Teaching and Travels Abroad

Harrison taught music at several colleges and universities. These included Mills College (twice), San Jose State University, and Reed College. In 1953, he moved back to California. He settled in Aptos, where he lived for the rest of his life.

He and William Colvig bought land in Joshua Tree, California. There, they designed and built a unique "straw bale house" called the "Harrison House Retreat." He continued to work on his experimental musical instruments.

Even though Asian music influenced him greatly, Harrison didn't visit Asia until 1961. He traveled to Japan and Korea, and then to Taiwan in 1962. In Taiwan, he studied with the zheng master Liang Tsai-Ping.

He and William Colvig later built their own percussion group. They used aluminum keys, tubes, and even oxygen tanks. They called it "an American gamelan" to show it was different from Indonesian ones. They also made gamelan-like instruments from tin cans and furniture tubing. Harrison wrote La Koro Sutro (in Esperanto) for these instruments. He also played and composed for the Chinese guzheng zither. With Colvig and others, he gave over 300 concerts of traditional Chinese music in the 1960s.

He was a composer-in-residence at San Jose State University in the 1960s. The university held a special concert in his honor in 1969. It featured dancers, singers, and musicians. A highlight was the first performance of Harrison's music telling the story of Orpheus.

Activism and Other Work

Harrison was open about his beliefs. He was a pacifist (someone who believes in peace and dislikes war). He strongly supported the international language Esperanto. He also believed in being true to himself.

He wrote many pieces with political messages or titles. For example, he wrote Homage to Pacifica for the opening of the Pacifica Foundation headquarters. He also accepted commissions from groups like the Portland Gay Men's Chorus. He arranged his Strict Songs for a large male chorus.

Like many composers, Harrison found it hard to earn a living only from his music. He took on other jobs to support himself. These included selling records, being a florist, an animal nurse, and a forestry firefighter.

Later Life and Legacy

On November 2, 1990, the Brooklyn Philharmonic performed Harrison's fourth symphony, which he called "Last Symphony." This piece combined Native American, ancient, and Asian music with orchestral sounds. It also included Navajo "Coyote Stories." He made some changes to the symphony, finishing the final version in 1995.

From the late 1980s, William Colvig's health got worse. He lost his hearing, and Harrison started learning American Sign Language to communicate. Later, Colvig's memory faded due to illness. Harrison cared for his partner for months. He was by Colvig's side when he passed away on March 1, 2000.

Death

Harrison and his partner Todd Burlingame were traveling to Ohio State University. A festival celebrating Harrison's music was planned there. On February 2, 2003, they stopped for lunch in Lafayette, Indiana. While inside, Harrison felt chest pains and collapsed. He passed away within minutes, likely from a heart attack. He was cremated as he wished.

Lou Harrison's Music

Musical Style and Techniques

Many of Harrison's early works use percussion instruments. These were often made from everyday items like garbage cans and steel brake drums. He also wrote pieces using Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique. This included his opera Rapunzel and his Symphony on G (Symphony No. 1). Some works feature the tack piano, which has small nails in the hammers for a more percussive sound.

Harrison's later music often used "melodicles." These are short musical ideas that are turned backwards or upside down to create the main musical pattern. His music is usually clear and simple in texture, but very melodic. Harmony is often simple or sometimes not used much. The focus is on rhythm and melody.

Ned Rorem described Harrison as mainly a melodist. He said rhythm was very important in his work, and that Harrison was one of the first American composers to successfully blend Eastern and Western music styles.

One technique he often used was "interval control." This means only a small number of specific musical intervals (distances between notes) are allowed. For example, in his Fourth Symphony, only minor thirds, minor sixths, and major seconds were allowed at the beginning.

Harrison's music also focused on the physical and sensory experience. This included live performances, improvisation, the sound quality (timbre), rhythm, and the feeling of space in his melodies. He often worked with dancers. The American choreographer Mark Morris used Harrison's Serenade for Guitar (1978) for a new kind of dance.

Harrison and Colvig built two full Javanese-style gamelan sets. One was named Si Betty, and the other, built at Mills College, was named Si Darius/Si Madeliene. Harrison held a special music composition chair at Mills College from 1980 until he retired in 1985.

He received the Edward MacDowell Medal in 2000.

Some of Harrison's well-known works include the Concerto in Slendro, Concerto for Violin with Percussion Orchestra, and Organ Concerto with Percussion (1973). His Double Concert (1981–82) is for violin, cello, and Javanese gamelan. He also wrote a Piano Concerto (1983–85) for Keith Jarrett. He composed four numbered orchestral symphonies.

Harrison knew several languages, including American Sign Language, Mandarin, and Esperanto. Several of his pieces have Esperanto titles and texts, like La Koro Sutro (1973).

Like Charles Ives, Harrison completed four symphonies. He often combined different musical forms and languages he liked. This is clear in his fourth symphony and his third symphony, which was performed by the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra.

Images for kids

-

Harrison considered Henry Cowell (pictured) his greatest musical inspiration and one of his closest friends

-

Harrison developed a deep interest in the traditional gamelan ensembles of southern Indonesia (pictured)

See also

In Spanish: Lou Harrison para niños

In Spanish: Lou Harrison para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |