Musical tuning facts for kids

In music, tuning an instrument means getting it ready to play. It makes sure that when you play a note, it sounds at the correct pitch. This means it's not too high or too low.

When two or more instruments play together, it's super important they are in tune. This way, when they play the same note, it sounds exactly the same. If instruments are out of tune, it sounds unpleasant. This is because two notes that are just a tiny bit different in pitch will create a "beat" sound.

Contents

Tuning Instruments

Some instruments, like the piano or organ, need special experts to tune them. But for most instruments, the musicians themselves need to tune before they play.

- Players of string instruments can turn the pegs at the top of their instruments. This changes how tight the string is.

- Players of wind instruments can make their instruments a little longer or shorter. They do this by pushing or pulling one of the joints.

- Timpani players turn taps around the top of their drums. This changes the tightness of the drum head.

When an orchestra plays a concert, all the instruments must tune carefully. This makes sure they sound good together. Usually, the main oboist stands up and plays the note A. Everyone then tunes their instrument to that A. In some places, like the US, the main violinist (concertmaster) gives the A note. If the orchestra plays with a piano soloist, they will tune to the piano's A. This is because the piano has already been tuned by a piano tuner.

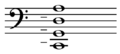

When a violinist tunes their instrument, they make sure their four strings are perfectly tuned. These notes are G, D, A, and E. Each string wraps around a peg near the top of the violin. Turning the peg changes the tuning. Violinists might also have "adjusters" or "fine tuners." These are at the other end of the string, where it connects to the tailpiece. Adjusters make it easier to make small changes to the tuning. The violinist first tunes the A string. Then, they play the A and D strings together. They make sure these two notes are exactly a fifth apart. They do the same for D and G, and finally for A and E.

If musicians are not tuning to a piano, they sometimes use a tuning fork. This fork gives an exact note, usually an A. This helps them know they are in tune. There are also electronic tuning devices that can help.

Tuning Systems

When an instrument like a piano is tuned, the tuner needs to know how each note should relate to the others. Over music history, people have used different ways to do this. These different tuning systems are about the exact scientific way notes in a scale relate. Musicians have discussed a lot about the best way to tune instruments.

The Pythagoras Problem

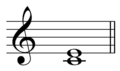

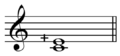

When two notes are an octave apart, the higher note vibrates twice as fast as the lower note. For example, if a string vibrates 440 times a second (440 Hz), you hear an A. This is the A above Middle C on a piano. If you press the string halfway, it vibrates at 880 Hz. You will then hear the A one octave higher.

A note that vibrates 1.5 times faster than a basic note will be a perfect fifth higher. For example, if C is the basic note, G is a perfect fifth higher.

Imagine a piano tuner starts by tuning a C. Then, they tune a G so it's exactly 1.5 times the frequency of the C. They can keep tuning notes in fifths (like D, then A, and so on). But if they keep going until they get back to a C, they will find that the last C is not perfectly in tune with the first C. This problem was found long ago by Pythagoras. It is called "the comma of Pythagoras."

Solving the Tuning Problem

For centuries, musical tuning systems have tried to fix this problem. From the 16th century onwards, many music theorists wrote books about how to best tune keyboard instruments. They often started by tuning notes a fifth up and a fifth down. This made those notes perfectly in tune (like C, G, and F). Then they would continue tuning other notes. Sometimes, old organs today are still tuned this way. When playing music in keys with few sharps or flats (like C, G, or F), the music sounds very beautiful. But playing in keys with many sharps or flats can sound very out of tune.

In 1584, a Chinese prince named Zhu Zaiyu wrote about inventing equal temperament. This was in his book A New Account of the Science of the Pitch-Pipes. In 1585, Simon Stevin also invented a similar system. Some experts think one of them truly invented it, while others think both did, or neither.

Around 1700, a famous composer named Johann Sebastian Bach used this new system. He wrote two books of 24 preludes and fugues. These were called the Well-Tempered Clavier. He wrote them to show that it was now possible to play music in any key, and it would sound good.

Main Tuning Systems for Twelve Notes

Here are some of the main ways people have tuned the twelve-note chromatic scale. These systems were made to solve the problem that you can't make all intervals sound "perfect" at the same time:

- Just intonation: In this system, the notes' frequencies are based on simple whole number ratios (like 3:2 or 5:4). Or, all pitches are based on the harmonic series. This system works well for instruments like lutes, but not for keyboard instruments.

- Pythagorean tuning: This is a type of just intonation. All notes' frequencies are based on multiples of the 3:2 ratio.

- Meantone temperament: This system averages out pairs of ratios for the same interval. This makes it possible to tune keyboard instruments better.

- Well temperament: This is a group of systems where the intervals are not all equal. But they are close to the ratios used in just intonation.

- Equal temperament (a special type of well-temperament): In this system, notes that are next to each other on the scale are all separated by exactly the same distance. This is the most common tuning system used today. It means all keys sound equally "good," even if no single interval is perfectly "pure."

Other pages

Images for kids

-

Tuning of Sébastien Érard harp using Korg OT-120 Wide 8 Octave Orchestral Digital Tuner

See also

In Spanish: Afinación para niños

In Spanish: Afinación para niños

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |