Pythagoras facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Pythagoras

|

|

|---|---|

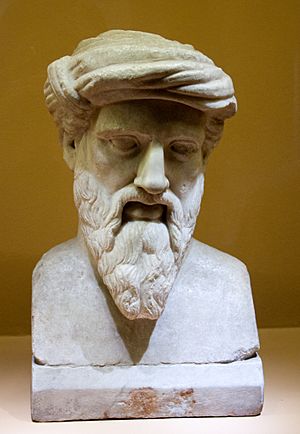

Bust of Pythagoras of Samos in the

Capitoline Museums, Rome |

|

| Born | c. 570 BC |

| Died | c. 495 BC (aged around 75) either Croton or Metapontum

|

| Era | Pre-Socratic philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Pythagoreanism |

|

Main interests

|

|

|

Notable ideas

|

Attributed ideas:

|

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Pythagoras of Samos (born around 570 BC, died around 495 BC) was an ancient Greek thinker and the founder of Pythagoreanism. He was a very important philosopher.

His ideas about politics and religion were well known. They influenced later famous thinkers like Plato and Aristotle. Through them, Pythagoras's ideas shaped much of Western thought.

People in ancient times believed Pythagoras made many discoveries. These included the Pythagorean theorem in math. He was also credited with Pythagorean tuning in music. Other ideas attributed to him include the five regular solids. He also developed the Theory of Proportions. He was said to be the first to suggest the Earth is round. He also identified the morning and evening stars as the planet Venus.

It is said that Pythagoras was the first to call himself a "philosopher." This word means "lover of wisdom." He was also believed to be the first to divide the world into five climate zones.

Contents

Life of Pythagoras

Early Years

Pythagoras's early life is surrounded by many stories. He was likely born around 570 BC on the island of Samos. His father, Mnesarchus, was a gem-engraver. His mother was Pythaïs, a local from Samos. A prophecy said she would give birth to a very wise and helpful man.

Pythagoras's name was linked to Pythian Apollo. Some thought his name meant he spoke truth like the oracle.

Pythagoras grew up when early Greek natural philosophy was developing. He lived at the same time as philosophers like Anaximander and Anaximenes. These thinkers lived in Miletus, which was close to Samos.

His Travels

Many believe Pythagoras got most of his education in the Near East. Like other important Greek thinkers, he was said to have studied in Egypt. Some ancient writers claimed he learned geometry and the idea of metempsychosis (souls moving between bodies) from Egyptians.

Other writers said Pythagoras learned from the Magi in Persia. Some even said he learned from Zoroaster himself. Diogenes Laërtius wrote that Pythagoras later visited Crete. By the third century BC, it was also said he studied with the Jews.

Greek Teachers

Some historians suggest Hermodamas of Samos was one of his teachers. Others mention Bias of Priene, Thales, or Anaximander. Pythagoras might have met Thales in Greece or Egypt before 520 BC. Thales was a famous philosopher and mathematician.

Life in Croton

Scholars agree that Pythagoras moved to Croton in southern Italy around 530 BC. There, he started a school. Students at his school promised to keep secrets. They lived a simple, disciplined life. This included rules about what they could eat, like vegetarianism. However, modern scholars are not sure if he was a strict vegetarian.

All sources agree that Pythagoras was very persuasive. He quickly gained political influence in Croton. He advised the leaders of the city. Later stories say his speeches inspired people to live better lives. They gave up their luxurious habits for his purer system.

Family and Friends

According to Porphyry, Pythagoras married Theano. She was from Crete. They had several children. Porphyry mentions two sons, Telauges and Arignote, and a daughter, Myia. Myia was said to be a respected woman in Croton. Other accounts mention a son named Mnesarchus.

The famous wrestler Milo of Croton was a close friend of Pythagoras. It is said that Milo once saved Pythagoras's life.

His Death

Pythagoras taught dedication and simple living. These ideas helped Croton win a big victory over Sybaris in 510 BC. After this win, some citizens wanted a democratic government. The Pythagoreans did not agree with this.

Supporters of democracy, led by Cylon and Ninon, turned people against the Pythagoreans. Cylon was reportedly angry because he was not allowed into Pythagoras's group. Cylon and Ninon's followers attacked the Pythagoreans during a meeting. The building was set on fire, and many members died. Only the younger members managed to escape.

Stories differ about whether Pythagoras was there during the attack. Some say he was away, visiting a dying friend. Other accounts say he escaped with a few followers. They went to Locris but were turned away. They then reached Metapontum. There, they took shelter in a temple and died of starvation after 40 days. Another story says his students made a path over their bodies for him to escape the fire. Pythagoras escaped but was so sad that he ended his own life.

A different legend says Pythagoras almost escaped but stopped at a fava bean field. He refused to run through it because it went against his teachings. So, he stopped and was killed. This story might have been about later Pythagoreans, not Pythagoras himself.

Legends About Pythagoras

Even during his lifetime, many amazing stories were told about Pythagoras.

- Aristotle described Pythagoras as a wonder-worker. He was seen as almost supernatural.

- Aristotle wrote that Pythagoras had a golden thigh. He supposedly showed it at the Ancient Olympic Games.

- It was said that a priest gave Pythagoras a magic arrow. He used it to fly long distances.

- He was supposedly seen in two places at the same time: Metapontum and Croton.

- When Pythagoras crossed the river Kosas, people reported hearing the river greet him by name.

- In Roman times, a legend claimed Pythagoras was the son of the god Apollo.

- Muslim tradition says Pythagoras was taught by Hermes.

- Pythagoras was said to always dress in white. He also wore a golden wreath on his head.

- Diogenes Laërtius said Pythagoras had amazing self-control. He was always cheerful but never laughed.

- Pythagoras was also said to be very good with animals. One story says he bit a deadly snake back and killed it.

- Both Porphyry and Iamblichus reported that Pythagoras convinced a bull not to eat fava beans. He also convinced a destructive bear to promise never to harm living things again. The bear kept its promise.

Scholars think Pythagoras might have encouraged these legends himself. However, there is no direct proof. Some negative legends also spread about him. One story says Pythagoras went into an underground room. He told everyone he was going to the underworld. He stayed there for months. His mother secretly wrote down everything that happened while he was gone. When he came back, Pythagoras told everyone what had happened. This made people believe he had been to the underworld.

Discoveries Attributed to Pythagoras

In Mathematics

Many mathematical and scientific discoveries are linked to Pythagoras. These include his famous theorem. He is also credited with discoveries in music, astronomy, and medicine.

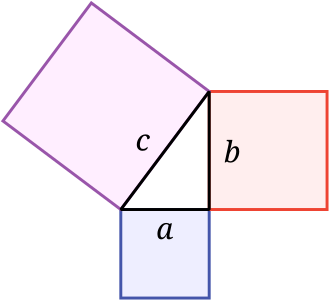

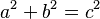

Since at least the first century BC, Pythagoras has been given credit for the Pythagorean theorem. This geometry theorem states that in a right-angled triangle, the square of the longest side (hypotenuse) is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides. This is written as  . A popular story says that after he discovered this, Pythagoras sacrificed an ox to the gods. However, some rejected this story because Pythagoras was believed to be against blood sacrifices.

. A popular story says that after he discovered this, Pythagoras sacrificed an ox to the gods. However, some rejected this story because Pythagoras was believed to be against blood sacrifices.

The Pythagorean theorem was known and used by the Babylonians and Indians centuries before Pythagoras. But he might have been the first to bring it to the Greeks. Some historians think he or his students might have created the first proof for it.

Pythagoras's biographers say he was also the first to identify the five regular solids. They also claim he was the first to discover the Theory of Proportions.

In Music

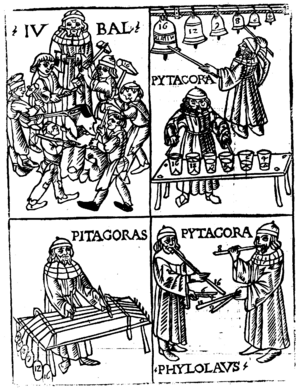

Legend says Pythagoras found that musical notes could be explained with math. One day, he heard blacksmiths working. Their hammers made harmonious sounds, except for one. He went into the shop and tested the hammers. He realized the sound was related to the hammer's size. From this, he concluded that music was mathematical.

In Astronomy

In ancient times, Pythagoras and Parmenides of Elea were both credited with some ideas. They were said to be the first to teach that the Earth was round. They also supposedly divided the world into five climate zones. They were also said to be the first to realize the morning star and the evening star were the same object, which is now known as Venus.

Parmenides has a stronger claim to these ideas. Empedocles, who lived after Pythagoras, knew the Earth was spherical. By the end of the fifth century BC, most Greek thinkers accepted this fact. The Babylonians knew the morning and evening stars were the same over a thousand years earlier.

See also

In Spanish: Pitágoras para niños

In Spanish: Pitágoras para niños