Herculaneum facts for kids

The excavations of Herculaneum

|

|

| Alternative name | Ercolano |

|---|---|

| Location | Ercolano, Campania, Italy |

| Coordinates | 40°48′22″N 14°20′54″E / 40.8060°N 14.3482°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | 6th–7th century BC |

| Abandoned | 79 AD |

| Site notes | |

| Website | Herculaneum – Official website: http://ercolano.beniculturali.it/ |

| Official name | Archaeological Areas of Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Torre Annunziata |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv, v |

| Designated | 1997 (21st session) |

| Reference no. | 829 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

Herculaneum was an ancient Roman town in Italy. It was buried by a huge pyroclastic flow when Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 AD. Today, the modern town of Ercolano sits above it.

Like Pompeii, Herculaneum is famous because it was preserved almost perfectly. The volcanic material that covered the town protected it from thieves and bad weather. Herculaneum was discovered first, in 1709, long before Pompeii was fully found in 1748.

What makes Herculaneum special is that the volcanic material turned many wooden objects into charcoal. This preserved things like roofs, beds, doors, and even food and ancient scrolls made of papyrus.

The town was found by accident in 1709 when someone was digging a well. For many years, people dug tunnels to find treasures. Proper excavations started in 1738 and have continued since then. Only a small part of the ancient city has been uncovered. Now, the main goal is to protect what has already been found.

Herculaneum was smaller than Pompeii, with about 5,000 people. It was a richer town, a popular place for wealthy Romans to relax by the sea. This is clear from the many fancy houses with colorful marble decorations. Important buildings include the Villa of the Papyri and the "boat houses," where the bones of at least 300 people were found.

Contents

Herculaneum's Ancient Story

The Greek hero Heracles (also known as Hercules) is said to have founded Herculaneum. However, historians believe the Oscans were the first to settle there. Later, the Etruscans took control, followed by the Greeks. The Greeks called it Heraklion and used it as a trading spot because it was close to the Gulf of Naples. In the 4th century BC, the Samnites took over the city.

Around the 2nd century BC, strong city walls were built. These walls were 2 to 3 meters thick and made mostly of large pebbles. Herculaneum joined other cities in the Social War (91–88 BC) against Rome but was defeated. After the war, the walls were no longer needed for protection and became part of houses.

Herculaneum became a Roman town in 89 BC.

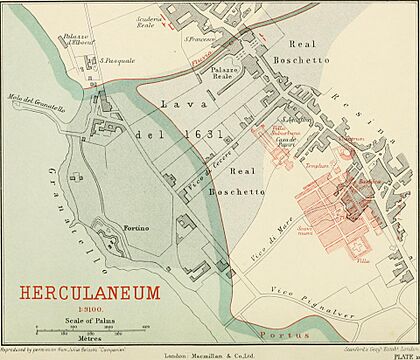

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD buried Herculaneum under about 20 meters (66 feet) of ash and rock. The city stayed hidden for over 1,600 years. It was slowly rediscovered through wells and tunnels, especially after the Prince d'Elbeuf's explorations in the early 1700s. Digging has continued off and on, and today many streets and buildings are visible. However, more than 75% of the town is still buried.

The modern towns of Ercolano and Portici now sit on top of ancient Herculaneum. Ercolano was called Resina until 1969, when it changed its name to honor the old city.

The Big Eruption of 79 AD

We know a lot about the eruption from archaeological finds and two letters written by Pliny the Younger. He wrote to the Roman historian Tacitus about what happened.

Around 1 PM on the first day, Mount Vesuvius shot volcanic material thousands of meters into the sky. Pliny described the huge cloud as looking like a stone pine tree. Winds blew the ash mainly towards Pompeii. Herculaneum, being west of Vesuvius, was not hit as hard at first. While roofs in Pompeii collapsed, Herculaneum only got a few centimeters of ash. This small amount of ash caused most people to leave the city.

The volcano kept erupting, sending ash and pumice high into the air. At 1 AM the next day, the eruptive column collapsed. This created the first pyroclastic surge, a fast-moving mix of hot ash and gases. It rushed down the mountain at about 160 kilometers per hour (100 mph) and swept through Herculaneum.

Six of these hot flows and surges buried the city up to 20 meters (66 feet) deep. In some areas, they caused little damage, preserving buildings and objects almost perfectly. In other places, the surges were powerful enough to knock down walls and move large objects. For example, a marble statue was blown 15 meters (49 feet) away.

Evidence suggests the eruption happened in October or November, not August. People found buried were wearing heavier clothes, not light summer clothes. Fresh fruits and vegetables found in shops were typical of autumn. Wine jars had been sealed, which usually happened in late October. Also, coins found in a woman's purse could not have been made before September.

Scientists have learned that the intense heat from the pyroclastic surges was the main cause of death. People died instantly from temperatures of at least 250°C (480°F). This extreme heat caused hands and feet to contract and even fractured bones and teeth.

Uncovering Herculaneum's Secrets

Prince d'Elbeuf started building a villa nearby in the early 1700s. He heard stories about wells containing old sculptures. In 1709, he bought a site where a well had been dug and tunneled from its bottom. This led him to what was later identified as a theater, where amazing sculptures were found. Two beautiful statues of "Herculaneum women" were among the first discoveries. Digging stopped in 1711 because people worried about the buildings above.

Major excavations began again in 1738, supported by Charles III of Spain. He appointed engineers to oversee the project. Books like "The Antiquities of Herculaneum" showed the world what was being found. This greatly influenced a new art style called Neoclassicism in Europe. By the late 1700s, designs from Herculaneum appeared on furniture and decorations. However, digging stopped again in 1762 due to criticism of the treasure-hunting methods. Also, the discovery of Pompeii, which was much easier to dig up (only 4 meters of material compared to 20 meters at Herculaneum), drew attention away.

King Francis I of the Two Sicilies ordered more land to be bought and restarted excavations between 1828 and 1837. Digging continued until 1875.

From 1927 to 1942, Amedeo Maiuri led a new project that uncovered about four hectares (10 acres) of the city. This area is now part of the archaeological park.

Between 1980 and 1981, hundreds of skeletons were found in the "boat houses" near the ancient shoreline.

More buildings, like the Villa of the Papyri and the northwest baths, were uncovered between 1996 and 1999. After this, a lot of work was done from 2000 to 2007 to preserve these new finds.

Many parts of the city, including the main public square (the Forum) and temples, are still buried underground.

Exploring the Ancient City

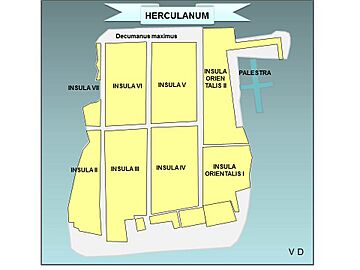

Herculaneum had a classic Roman street plan, dividing the city into blocks called insulae. These blocks were created by streets running east-west (cardi) and north-south (decumani).

Because of slow ground movement called bradyseism, parts of Herculaneum are now up to 4 meters (13 feet) below sea level.

The city had a good water system. A main drain collected water from the Forum, house courtyards (impluviums), toilets (latrines), and kitchens. Other drains went directly into the street. The city got its water from the Serino aqueduct, built during the time of Emperor Augustus. Water flowed through lead pipes under the roads, controlled by valves. Before this, people used wells.

The House of Aristides (Ins II, 1)

This house is the first building in block II. Its entrance leads into the main hall (atrium). The ruins are not very well preserved because of damage from earlier digs. The lower floor was likely used for storage.

The House of Argus (Ins II, 2)

This house is named after a painting of Argus and Io that used to be in a reception room. It was probably one of Herculaneum's most beautiful villas. When it was found in the 1820s, it was the first time a second story had been uncovered in such detail. Diggers found a balcony overlooking a street and wooden shelves, which are now gone.

The House of the Genius (Ins II, 3)

North of the House of Argus is the House of the Genius. Only part of it has been uncovered, but it seems to have been a very large building. Its name comes from a statue of a Cupid that was once part of a candlestick. In the middle of its courtyard, there are remains of a rectangular pool.

The House of the Alcove (Ins IV)

This house is actually two buildings joined together. It has a mix of simple rooms and beautifully decorated ones.

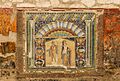

The main hall (atrium) is covered and does not have the usual central pool (impluvium). It still has its original floor, made of colorful small tiles (opus tesselatum) and cut stone (opus sectile). A richly decorated dining room (biclinium) with paintings in the fourth style and a large dining room (triclinium) with marble floors were found off the atrium. Other rooms, including the curved alcove that gives the house its name, are reached through a hallway that gets light from a small courtyard.

College of the Augustales

This was a temple for the Augustales, who were priests of the Imperial cult. They honored the Roman emperors.

Central Baths

The Central baths (thermae) were built around the 1st century AD. They had separate areas for men and women to bathe. These baths were also important social centers where people met and relaxed.

The Villa of the Papyri

The famous Villa of the Papyri was built on four terraces by the sea. It is believed to have belonged to Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, who was Julius Caesar's father-in-law. He loved poets and thinkers, and he built the only ancient library that has survived almost completely.

Between 1752 and 1754, workers found many blackened, unreadable papyrus scrolls in the Villa of the Papyri. These are known as the Herculaneum papyri or scrolls. Most of them are now kept at the National Library in Naples. Even though they were badly burned, some scrolls have been unrolled with some success. Special computer imaging using infrared light helped make the ink visible. Now, there is hope that unopened scrolls can be read using X-rays. This would avoid damaging them by unrolling. Later CT scans showed the scrolls' fiber structure and trapped debris, helping with safer unrolling, but the text remained unreadable.

In 2015, scientists used X-ray Phase Contrast Tomography to make the carbon ink stand out from the carbon-based papyrus. This allowed them to read Greek words on the outside of a scroll, which was a big step for experts who study ancient writings. While some words can be identified, the full stories on the scrolls are still a mystery.

In 2024, winners of a contest called the Vesuvius Challenge used AI to reveal hundreds of words from 15 columns of text, which is about 5% of one scroll.

Boathouses and the Shore

In 1980–82, archaeologists found over 55 skeletons on the ancient beach and in the first six "boat sheds." Before this, people thought most residents had escaped. This discovery changed that idea. The people waiting for rescue by sea were likely killed instantly by the extreme heat of the pyroclastic flow, even though they were sheltered. Studies of their bones show that the first surge caused instant death from temperatures around 500°C (930°F).

After some problems with how the bones were handled, more digs in the 1990s found 296 more skeletons. These were on the beach or huddled in 9 of the 12 stone vaults facing the sea. While most of the town was empty, these people were trapped. The "Ring Lady," named for the rings on her fingers, was found here in 1982.

In total, 340 bodies were identified in this area. Analysis of the skeletons suggests that mostly men died on the beach, while women and children sought shelter and died in the boat houses.

A 2021 study used chemical analysis of the bones to learn about the health and diet of Herculaneum's people. It showed that men ate 1.6 times more fish than women, who ate more meat, eggs, and dairy. This matches what we know about diets in Roman Italy.

Casts of skeletons were also made to replace the original bones after scientific study. Unlike Pompeii, where plaster casts show the body shapes of victims, Herculaneum's victims' flesh vaporized instantly. So, casts here show the skeletons. A cast of skeletons from chamber 10 is on display at the Museum of Anthropology in Naples.

A special study in 2021 looked at one skeleton (number 26) found in 1982 on the beach next to a boat. The remains belonged to a military officer, perhaps involved in a rescue mission. He had an elaborate dagger and belt.

Keeping Herculaneum Safe

The volcanic ash and extreme heat kept Herculaneum incredibly preserved for over 1,600 years. But once digging started, being exposed to the air and weather began to cause damage. Early digging methods often focused on finding valuable artifacts rather than protecting the site itself. Protecting the human remains became a top priority only in the early 1980s.

Too many tourists, vandalism, poor management, and political issues have also harmed many sites and buildings. Water damage from the modern town of Ercolano has weakened many building foundations. Some attempts to rebuild have actually caused more problems. However, recent efforts to protect the site have been more successful. Digging has been paused to focus all money on conservation programs.

Many artifacts from Herculaneum are kept in the Naples National Archaeological Museum.

Modern Conservation Efforts

After years of neglect, Herculaneum was in bad shape. But in 2001, the Packard Humanities Institute started the Herculaneum Conservation Project. This is a partnership between private groups and local authorities. It first provided money to fix urgent problems. Later, it grew to include expert support and a long-term plan for the site. Since 2001, the project has worked on conservation and partnered with the British School at Rome to train students to maintain the site.

One project focused on a room called the tablinum that had been preserved in 1938. Over time, water seeped into the wall, causing the paint to peel away. Working with the Getty Museum, conservators found a way to use special liquids to remove some of the old wax and stop the paint from chipping.

Images for kids

-

Most likely a posthumous painted portrait of Cleopatra VII of Ptolemaic Egypt with red hair and her distinct facial features, wearing a royal diadem and pearl-studded hairpins, from Roman Herculaneum, mid-1st century AD

Documentaries About Herculaneum

- A 1987 National Geographic special, In the Shadow of Vesuvius, explored Pompeii and Herculaneum. It interviewed archaeologists and looked at the events leading to the eruption.

- The 2002 documentary "Herculaneum. An unlucky escape" is based on research by Pier Paolo Petrone, Giuseppe Mastrolorenzo, and Mario Pagano.

- An hour-long drama for the BBC called Pompeii: The Last Day showed characters living in Pompeii, Herculaneum, and around the Bay of Naples during their last hours. It also showed the facts of the eruption.

- "Secrets of the Dead: Herculaneum Uncovered" is a PBS show about the archaeological discoveries at Herculaneum.

- "Out of the Ashes: Recovering the Lost Library of Herculaneum" is a KBYU-TV documentary. It tells the story of the Herculaneum papyri from the eruption to their discovery and modern study.

- "The Other Pompeii: Life and Death in Herculaneum" is a documentary presented by Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, who directs the Herculaneum Conservation Project.

- "Unearthed: Vesuvius' Secret Victim." This documentary explores Herculaneum and its people. It revealed that over 1,000 of Herculaneum's 5,000 citizens survived the eruption and moved to Naples and Cumae.

See also

In Spanish: Herculano para niños

In Spanish: Herculano para niños

- List of Roman sites

Resources

- Pliny the Younger's letters about the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 A.D. to the Roman historian Tacitus: Pliny the Younger, Letters 6.16 and 6.20 to Cornelius Tacitus and in Project Gutenberg: Letter LXV – To Tacitus, Letter LXVI – To Cornelius Tacitus

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |