Samnites facts for kids

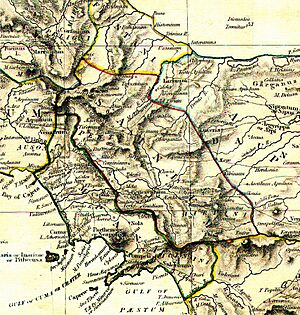

The Samnites were an ancient people who lived in a region called Samnium. This area is now part of central Italy, including parts of Abruzzo, Molise, and Campania. They spoke a language called Oscan and were related to the Sabines, another ancient Italian group.

The Samnites formed a group of four main tribes: the Hirpini, Caudini, Caraceni, and Pentri. They were known for being strong fighters.

Even though they were allies with the Romans against the Gauls in 354 BC, they later became enemies. They fought Rome in three major conflicts known as the Samnite Wars. Despite winning a big battle at the Caudine Forks in 321 BC, the Romans eventually defeated the Samnites in 290 BC.

After their defeat, the Samnites were much weaker. However, they still sometimes fought against Rome. They joined King Pyrrhus in the Pyrrhic War and later helped Hannibal during the Second Punic War. They also fought in the Social War and Sulla's civil war, but were defeated again. After these wars, the Romans absorbed the Samnites into their society, and they stopped being a separate people.

The Samnites mostly made their living from farming and raising animals. Their farming methods were quite advanced for their time. They also traded goods like pottery, bronze, iron, and wool with other regions in Italy.

Samnite society was organized into groups called cantons. Small towns were called vici. Many vici formed a pagus, and several pagi made up a touto, which was a tribe. There were four Samnite touto, one for each tribe. Some Samnite cities also had councils, similar to a Roman Senate. The tribes usually acted on their own, but sometimes they would unite for important reasons, like war.

The Samnites believed in spirits called numina and worshipped various gods and goddesses. They honored their gods by sacrificing animals and offering gifts. They also believed in magic and that certain people could see the future. Priests managed religious festivals. Sanctuaries were important places for worship, trade, and even marking borders.

What's in a Name?

The name "Samnites" comes from an old word, Safin. This word might have been used to describe the Samnite people and their land. It is believed to be related to the name of the Sabines, another ancient Italian group.

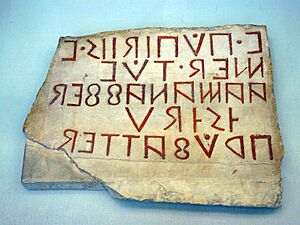

The Oscan word for Samnium was Safinim, which meant "cult place of the Safin people." This led to the name Safineis for the Samnite people. The Greeks also had names for them, like Samnītēs. Some people think these names came from saunion, the Greek word for "javelin," because Samnites were known for using javelins.

Samnite History

Where Did the Samnites Come From?

The Greek writer Strabo said that the Samnites came from a group of Sabines who left their homeland. According to this story, the Sabines promised to sacrifice everything produced in a year, including babies, if they won a war or ended a famine. When these babies grew up, they were sent away, guided by a bull to a new land. Once there, they sacrificed the bull to the god Mars.

Other Samnite tribes said they were guided by different animals, like a wolf or a woodpecker. Some stories even linked the Samnites to the Spartans of Greece. These old legends might not be entirely true. They could have been created by the Greeks to connect the Italian people to their own history. However, archaeological findings suggest that Samnite culture grew from older Italian groups already living in the area.

After the Etruscans left Campania in the 400s BC, the Samnites took over the region, including cities like Pompeii and Herculaneum. They might have wanted the rich farmland or access to rivers and other resources. They also conquered many Greek cities, but failed to take Naples. Over time, they fought more wars against the Campanians, Volscians, and other Latin groups.

The Samnite Wars

The Samnites and Romans first met after Rome conquered the Volscians. In 354 BC, they agreed on a border at the Liris River. However, a Roman historian named Livy wrote that the Samnites attacked the Campanians, who then asked Rome for help. This led to the First Samnite War in 343 BC. Modern historians are not sure if this is the exact reason the war started. After three defeats and a Roman invasion, the Samnites signed a peace treaty.

The Second Samnite War started for different reasons. Rome might have declared war because the Samnites allied with the Vestini or fought against other Roman allies. Also, Rome wanted to control the rich city of Venafrum. After the Romans lost badly at the Battle of the Caudine Forks, both sides agreed to a break. Fighting started again in 326 BC and ended after Rome attacked Samnium and Apulia. Rome then took over some Samnite lands.

In 298 BC, the Third Samnite War began because of problems with the Lucanians, who asked Rome for protection. This war ended after the Samnites lost at the Battle of Aquilonia. After this, Samnium was conquered, and the Samnites became part of Roman society.

Later Samnite History

The Samnites were among the Italian peoples who joined King Pyrrhus of Epirus during the Pyrrhic War. After Pyrrhus left for Sicily, the Romans invaded Samnium. The Samnites defeated them at the Battle of the Cranita Hills. But after Pyrrhus was defeated, the Samnites could not fight Rome alone and surrendered.

Some Samnites later helped Hannibal during the Second Punic War, but most stayed loyal to Rome. When the Romans refused to give the Samnites Roman citizenship, they rebelled with other Italian peoples in the Social War. This war lasted almost four years and ended with a Roman victory. After this bloody conflict, Samnites and other Italian tribes were finally given citizenship to prevent more wars.

The Samnites supported Marius and Carbo in the civil war against Sulla. The Samnites and their allies, led by Pontius Telesinus, gathered a large army of 40,000 men. They fought Sulla at the Battle of the Colline Gate, but lost. Pontius was executed after the battle.

After Sulla won the civil war and became dictator of Rome, he punished those who had opposed him. The Samnites were punished very harshly. Many of their cities became small villages or were completely empty. After this, the Samnites no longer played a big role in history. They slowly adopted Roman culture and became part of the Roman world. However, some of their families later became important Romans.

Samnite Society

Samnite Economy

Most of Samnium was rugged and mountainous, with few natural resources. Because of this, the Samnites had a mixed economy. They focused on using the small areas of fertile land for farming, raising animals, and small farms. Their successful farming likely led to conflicts with other groups, possibly even causing the Samnite Wars.

Raising animals like horses, cattle, goats, pigs, and sheep was very important to the Samnite economy. These animals were valuable for trade and as food. Transhumance, which is moving livestock between summer and winter pastures, was a key part of their economy. Short-distance transhumance helped wealthy families.

During the 400s and 300s BC, the Samnite population grew. Trade with other Italian groups also helped their farming and city development. The city of Larinum, for example, became a major grain producer and a center for all economic activity in the Biferno Valley. The Samnites exported goods like grains, olives, wine, bronze, iron, and textiles. They also imported items like bronze bowls and pottery from places like Campania and Etruria. These trade networks helped them adopt products and ideas from other cultures.

Samnite money started to develop in the late 400s and early 300s BC, likely because of trade with the Greeks and the need to pay soldiers. Their bronze or silver coins might have been made in Naples or by Samnite cities themselves. Coins often showed places like Allifae or people like the Campani. These images were linked to the development of Samnite government. Coins might not have been used by individuals but by government groups to pay for tasks. After this early period, the Samnites made less money.

The Samnites likely produced a lot of wool and leather, as many loom weights have been found in Samnium. These weights were used in weaving. They often had patterns like pyramids, stars, or crosses. Some patterns were shaped like leaves, flowers, or mythological figures. Greek words found on Samnite pottery might have told weavers how to arrange threads or marked the quality or weight of the cloth.

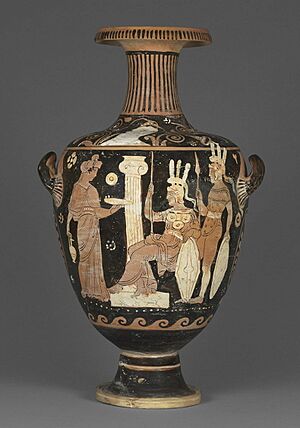

The Samnites also made amphorae (large storage jars), terracottas, and black pottery. They often used a protective coating on their pottery. Most amphorae were imported from Rhodes, and pottery often came from Greece. After Samnite society became more urban, they produced much more Hellenistic (Greek-influenced) or Italian pottery. Pottery and amphorae often had patterns, which were usually trademarks or signatures from the craftsmen. Sometimes, they showed places or named government officials.

Samnite Government

During the Iron Age, Samnium was ruled by chiefs and wealthy families. In the early 300s and 200s BC, the Samnite political system changed to focus on rural settlements led by elected officials.

Samnite settlements, called vici, were the lowest level of their social system. Many vici were grouped into pagi, which were like cantons. An elected official called a meddiss ran each pagus. The pagi were organized into toutos, which were the Samnite tribes. Each touto was led by an official elected every year, called the meddíss túvtiks. This official had supreme executive and judicial powers.

Political groups similar to councils or senates, like the kombennio, might have existed. The Kombennio was a democratic group in Pompeii that elected officials and made laws. Senates were located in the capitals of the Samnite tribes, such as Bovianum, the capital of the Pentri. It is not clear if these types of governments existed before the Romans conquered them. Even with these democratic groups, a few wealthy families still controlled Samnite society.

Each Samnite tribe usually acted independently. However, sometimes they would form an alliance, similar to the Latin League. This alliance was mainly for military purposes, with a commander-in-chief leading it. For the alliance to pass laws, the leaders of each tribe had to agree. Such alliances were rare, and some tribes might refuse to join. It is also possible that cities had more political power than the tribes in this organization.

This government system continued after the Roman conquest, but with less power. The touto and pagus became like small republics, while the vicus stayed the same. The Romans only interfered by having the Municipum (a Roman town) in charge of all older institutions.

Samnite Military

Roman historians believed that Samnite society was very focused on war. They feared Samnite cavalry (soldiers on horseback) and infantry (soldiers on foot), calling them Belliger Samnis, meaning "Warrior Samnites." It is not clear if this is completely true, as most Roman accounts were written after the Samnites had disappeared and might have been propaganda.

In early Samnite history, the military was made of trained warriors led by local leaders. Only wealthy people could access military equipment. Poorer people usually worked in farming. Samnite soldiers were trained from a young age in places like the triangular forum in Pompeii, as part of a group called the Vereiia. After the Roman conquest, the Vereiia became a community service group. During the Samnite Wars, the army changed to be more like the armies of ancient Greek city-states. They used formations like phalanxes and groups of 400 men called cohorts. This made their army flexible enough to fight in mountainous areas. Lower-class people were also recruited, making the army larger, but these recruits were less skilled.

Livy, a Roman historian, mentions a legio linteata ("linen legion"). This unit used special equipment to stand out. According to Livy, this legion swore an oath in a linen structure never to run away from battle. Scholars think this description might have been made to show the difference between "civilized" Romans and their "barbaric" enemies. However, some archaeological evidence suggests there might be some truth to the story.

Samnite Armor

Samnite soldiers wore a small, single-disc breastplate called a kardiophylax. It had straps that went around the shoulders, chest, and back. Even though a triple-disc breastplate offered more protection, the single-disc one was still used as a symbol of status. There were three types of triple-disc breastplates, all made with three discs in a triangular shape.

Wide belts made of leather, gold, or bronze were common and important to Samnite culture. They likely protected the stomach area. These belts were made by heating tin alloys and then shaping them with hammers to look like silver.

Samnite helmets were similar to Greek military helmets, with cheek guards, crests, and plumes. Crests were often made by attaching horse tails to a metal piece at the back of the helmet. Feathers and horns were also common on Samnite crests. Soldiers would put on their greaves (shin armor) by resting their leg on a rock. This armor reached the ankle and was likely custom-made. There are few pictures of Samnite soldiers wearing greaves, suggesting they were mostly used for rituals or mock-fights.

Samnite Weapons

Samnites commonly used spears and javelins. Spearheads were made from two bronze or iron parts. If a soldier ran out of projectiles, they would even throw rocks.

Besides spears, soldiers used swords or fought hand-to-hand. Old pottery and statues show Samnite soldiers using a type of Bronze Age sword called an "antenna sword." Another sword linked to the Samnites is the short sword. Samnite art shows soldiers getting swords in special ceremonies, meaning short swords were highly valued. Maces were less common than spears but still used. Axes were rare and might have been symbols of power.

There is not much archaeological evidence of Samnite shields because most of their parts have been destroyed. Samnite art often shows soldiers using a round shield called an aspis. They used two straps to carry the shield. The Samnites might also have used bronze oval shields. It is possible that the Samnite scutum (a type of shield) influenced the Roman shield, but this is not clear. Livy described the Samnite shield as wide near the shoulder and chest but thinner near the feet, but archaeological evidence does not support this. Livy might have confused a Samnite gladiator's equipment with a soldier's.

Samnite Culture

Samnite Religion

Superstition was a big part of Samnite culture. They believed magic could affect reality and tried to see the future. Spirits called numina were also important in their beliefs. It was important to have good relationships with these spirits, who later became the Samnite gods and goddesses. We know that gods like Vulcan, Diana, and Mefitis were worshipped, with Mars being the most important. To honor their gods, they offered gifts and sacrificed animals. In a practice called the Ver Sacrum, everything produced in a certain year would be exiled or offered to the gods. Some historians think Livy might have made up parts of these descriptions for propaganda.

Samnite graves often contained goods, especially for wealthy people, who had statues or stone markers. These items showed the person's wealth and status in life. Burial was likely a sign of high social status, as it was rare, even though Samnites believed in an afterlife.

Sanctuaries were very important in Samnite religion. They were used for many things: collecting money from trade routes, marking borders, serving as places of worship and communication, and even playing a role in government. Over time, sanctuaries became less important and were eventually abandoned.

Gender Roles in Samnite Society

Samnite women mainly had two roles: domestic and ceremonial. Women likely did a lot of weaving, which was important for the economy. They might also have had some political influence through banquets, similar to ancient Greek or Etruscan ones. Other duties included teaching young girls to dance, raising children, and managing the household. We don't know much about the relationships between Samnite wives and husbands. Scenes of pouring wine might suggest that wives were expected to be loyal to their husbands. Women might have been able to gain a lot of wealth, or they might have only been able to show off their partner's wealth. Art and pottery show Samnite women involved in rituals or near altars, offering wine or praying for their husbands before they went to fight.

The geographer Strabo wrote that the Samnites would choose ten of the "best" women and ten of the "best" young men and marry them. Then, the next best would be paired, and so on. The "best" might have been chosen based on athletic skills. If anyone dishonored themselves, they would be separated from their partners.

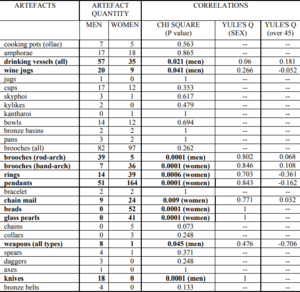

Samnite society might have had clear roles for men as warriors and women as "bejeweled." Ancient historians often describe Samnites as warlike, but this might be propaganda. Pottery from Campania often shows Samnite warriors fighting, while pottery from Apulia shows them in more varied situations. Differences in graves also support this idea: men were buried with weapons and armor, while women were buried with household items like spindles or jewelry. Young adult women were often buried with items like coils, pendants, and beads, similar to those worn by boys. This might mean that femininity was linked to youth in Samnite culture. Men wore smaller, simpler pins, possibly showing that male identity was linked to maturity.

Skeletons of men and women show differences in injuries. Male skeletons found near Pontecagnano Faiano had more head injuries than female skeletons. This suggests that Samnite men were expected to be warriors and fight, while women were not.

However, many graves do not follow these patterns. Some Samnite men were buried with items usually linked to women, and a few women were buried with weapons. Only a small percentage of men in Campo Consolino were buried with items typically for their gender. This could mean that these items were not about daily responsibilities but were offerings to the dead. The rarity of some burial goods might mean they were only for high-status people. For example, jewelry could show wealth or femininity. Differences in jewelry for young women might have been for protection during childbirth.

Skeletons show that both genders had fractures and injuries, though men had them more often. This could be because more male skeletons were found. Other skeletons show similarities between the lives of men and women. For example, both had healthy teeth, suggesting good diets. Art shows groups of both men and women honoring both dead men and women, meaning they could be honored in similar ways after death. Each gender might have had different but equally important roles. Another idea is that Samnites had two gender categories: adult males, and everyone else.

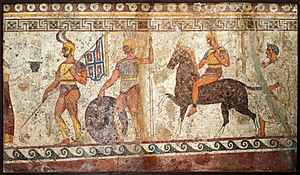

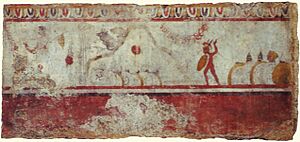

Samnite Art

The first art style used by the Samnites in Pompeii developed when Greek painters came to Italy to paint for wealthy families. It combined elements from Greek, Etruscan, and other Italian art. For example, showing important figures larger, clothing showing status, captions, storytelling, and historical depictions were all borrowed from other cultures.

Samnite art included colorful murals and paintings. The murals often used black or red cement floors with designs. There were two styles of floor mosaics: miculatum, which used marble and terracotta pieces, and oppus tessellatum, which looked like weaving. Samnite art was usually colorful and often showed myths, warriors, or Greek subjects. Murals in Pompeii were designed to create a peaceful, ideal feeling.

Other Samnite artworks have survived. On the walls of a sanctuary in Pietrabbondate, there is a relief that might be an atlas (a figure holding up something). Another possible Samnite or Roman artwork in Isernia shows two helmeted warriors. The Warrior of Capestrano statue might be an example of Samnite figurative art, but it was found in Vestini territory and shows a Picentine warrior.

Samnite Clothing

Most Samnite clothes were loose, draped, folded, and not stitched or sewn. Clothing had symbolic and ritual meanings. For example, clothes showed social status, and tunics were often used in ceremonies. The most valuable clothing was a bronze or leather belt covered in bronze.

Men wore rings, amulets with snake heads, and collars. Collars usually had holes for amulets and pendants and were decorated. Men received collars as boys and never took them off. Bearskins were also common clothing.

Women's clothing was similar to Greek clothes. Women wore long, sleeveless dresses, caps, hats, tunics, decorated belts, and chatelaines (chains with useful items). An important part of Samnite women's clothing was long garments that touched the ground. They also wore colored capes fastened under the chin with a brooch. Samnite capes covered the upper body, arms, and legs, but necklaces and amulets were still visible. Women also wore a jacket-like cape with sleeves, fastened at the front, and fitting tightly. Samnite skirts were heavily influenced by Greek clothing. Women wore head coverings made from folded cloth or hairnets under cylindrical headdresses.

Some clothing was worn by both men and women. Red, white, or black belts with patterns, usually made by hooking cloth or leather into holes, were worn by both genders.

It was common in ancient Samnium for both men and women to go barefoot. However, many shoe styles existed. Some shoes were low, some reached the ankles, and others had a small hole at the tip. Styles of footwear did not vary much between genders, except for boots. Women's boots were usually ankle-high, while men's boots were taller. White buttons and lines were used to secure shoe laces. Samnite sandals had white soles with a strap to attach them to the foot. Some sandals left the foot uncovered, while others covered it. Socks might have existed, or a soft fabric might have been used instead.

Italian pottery and Samnite tomb paintings show Samnite warriors wearing tunics. These were usually made from one piece of cloth and decorated with black or white patterns, mostly on the sleeves. Tunics were held at the waist by wide leather belts.

Livy described Samnite soldiers wearing two kinds of clothing. One was called versicolor, meaning it used contrasting colors. These clothes might have been designed to look like a chameleon or to show the Samnites were worthy opponents of Rome. They might also have symbolized wealth. The other group of Samnites wore silver clothing and carried weapons.

Samnite Recreation

Eating and drinking were very important to Samnite life. It was a way to have fun, build social connections, and discuss politics or work. The host would share food and drinks with guests. Wine was rarely given to adult men but was consumed by others. Banquets used large containers for mixing drinks, serving vessels, and small cups for individuals. Large containers were often amphorae or kraters. Serving vessels were usually dippers or jugs. Smaller vessels included cups and beakers. These items were often imported, for example, bucchero pottery came from Etruria.

Gladiatorial games might have started in Samnium. Roman and Greek writers like Livy and Strabo mention that wealthy families in Campania hosted gladiator games during their banquets. It is possible that the Samnite gladiator type came from these Oscan and Samnite games. However, there is not enough evidence to be sure. Other scholars think gladiatorial games came from Etruria, the Celts, or the city of Mantineia. Art from Campania shows Samnites in gladiatorial games. One artwork shows a dead gladiator with a spear in his head, suggesting the Samnites were not against brutality. Art also shows large gladiatorial games with chariot racing and banquets, meaning they were grand events for entertainment. Alternatively, these games might have been held at funerals. Games are often shown near funerals, and pomegranates, symbols of the afterlife, are in the background. The warriors in these funeral games are shown wearing colorful armor.

Chariot racing and hunting with javelins were recreational activities for Samnite men. In Pompeii, ancient Roman baths were built when the Samnites ruled the city.

Samnite Cities and Buildings

From the Bronze to the Iron Age, the number of Samnite settlements greatly increased. Most were small, with people living in hamlets and working. These small settlements were organized around larger ones, like Saepinum and Caiatia. Samnite cities were generally not as big as others in Italy. They were often disorganized and lacked central urban areas. Roads called tratturi connected summer and winter pastures. Samnite cities had buildings like temples, dining complexes, houses, and sanctuaries. Their cities did not have buildings like a Roman forum or a Greek agora, except for Pompeii, which had a small, irregular forum.

Samnite cities began building walls and other defenses during the Samnite Wars. Walls were usually rough and crude, located on hilltops without other defenses nearby. This suggests they were built to allow the defending army to retreat and regroup, rather than to fully protect the city. City gates were heavily fortified on the left side but not the right. This was done to force attacking soldiers to use their unprotected right side.

Hillforts with polygonal walls might have been common defenses or a type of settlement that showed a change from a rural to a more urban society. It is unclear if these hillforts were permanent defenses, as they might have been lived in only temporarily. Scholars have suggested other uses for Samnite hillforts, such as playing a role in government or being used to send fire signals.

Samnite architecture in Pompeii or Herculaneum often looked like Greek architecture. For example, they borrowed palaestras (gyms), colonnades, and columns from the Greeks. Other building techniques came from the Etruscans. The Samnite palaestra in Pompeii was a rectangular courtyard surrounded by porticos and Doric columns made of tufa stone. This building was similar to Greek palaestras and was likely a gymnasium, religious site, or campus. Houses were built on foundations with smaller blocks. Walls were usually made of rubble, which could be carved to look like stone blocks. Layers of plaster were spread over the walls, and frescoes (paintings on wet plaster) were made. Another material called stucco was often painted to make a house look like it was covered in marble. Atriums (open courtyards) were common in Samnite houses. They had impluviums (basins for rainwater), loggias (covered walkways), and cellae (small rooms). Outside the houses, there were tuff facades, shops, peristyles (courtyards with columns), and cornices (decorative moldings) with figurines. Roofs had stone downspouts and tiles.

Small, personal farms or houses were common. One farmhouse near Campobasso had a square stable house and rooms with hearths around a courtyard. It had basins and containers for processing and storing produce. Another farmstead was built in 200 BC using limestone blocks. An archaeological site called "ACQ 11000" had a terrace covered in thick clay, a walled space with a paved floor, and a stone wall.

Famous Samnites

Samnite Leaders

- Gaius Pontius (around 320s BC)

- Gellius Egnatius (around 296 BC)

- Herennius Pontius, a Samnite philosopher.

- Brutulus Papius, a Samnite noble mentioned by Livy.

- N. Papius Mr. f, a chief magistrate in 190 BC.

- Statius Gellius, a general during the Samnite Wars.

- Staius Minatius, a general during the Samnite Wars.

- N. Papius Maras Metellus, a chief magistrate in 100 BC.

- Numerius Statius, a chief magistrate in 130 BC.

- Gaius Statius Clarus, a chief magistrate around 90 BC.

- Olus Egnatius, a chief magistrate in the 2nd century BC.

- Titus Staius, a chief magistrate in the 2nd century BC.

- Gnaeus Staius Marahis Stafidinus, a chief magistrate in the 2nd century BC.

- Ovius Staius, a Samnite in the 2nd century BC. He might have built a statue to Hercules.

- Gaius Statius Clarus, a Samnite who built a podium in a temple.

- Stenis Staius Metellus, a chief magistrate in 130 BC. He possibly built a sanctuary.

- Maras Staius Bacius, a builder of a sanctuary.

- Pacius Staius Lucius, a builder of a sanctuary.

- Papius N. f, a chief magistrate in 160 BC.

- C. Papius Met. f, a chief magistrate in 130 BC.

- N. Papius Mr.f. Mt. n, a chief magistrate in 100 BC.

- L. Staius Ov. f. Met. n, a chief magistrate in Bovianum in 130 BC.

- Minatius Staius Stati f, a chief magistrate of Bovianum and Pietrabbondante in 120 BC.

- L. Staius Mr. f, a chief magistrate in 120 BC.

- Staius Sn. f, a chief magistrate in 100 BC.

- Gaius Papius, builder of a temple.

Social War Leaders

- Gaius Papius Mutilus, who served as a chief magistrate.

- Pontius Telesinus, who died in 82 BC.

- Marius Egnatius, a general in the Social War.

Romans of Samnite Origin

- Gaius Cassius Longinus – one of the people who assassinated Julius Caesar.

- Pontius Pilate – the Roman governor of Judea from AD 26–36. He ordered the crucifixion of Jesus.

- Caecilius Statius – a Roman comic poet who might have been of Samnite origin.

Catholic Popes

- Pope Felix IV – Catholic Pope from 526 to 530 AD.

See also

- Frentani

- Samnite Wars

- List of ancient Italic peoples

- Sabellians

|

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |