Pompeii facts for kids

View of Pompeii and Mount Vesuvius

|

|

| Location | Pompei, Metropolitan City of Naples, Campania, Italy |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°45′0″N 14°29′10″E / 40.75000°N 14.48611°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | 64 to 67 ha (170 acres) |

| History | |

| Founded | 7th–6th century BC |

| Abandoned | AD 79 |

| Official name | Archaeological Areas of Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Torre Annunziata |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, iv, v |

| Designated | 1997 (21st session) |

| Reference no. | 829 |

| Region | Europe |

Pompeii (pronounced pom-PAY-ee) was an ancient city in Italy, near the modern city of Naples. It was a busy Roman town that was completely buried by a huge volcanic ash and pumice eruption from Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD.

The ash preserved Pompeii almost perfectly, like a time capsule. This gives us a special look into what Roman life was like nearly 2,000 years ago. It was a rich city with between 10,000 and 20,000 people.

Pompeii had many beautiful public buildings and fancy private homes. These homes were decorated with amazing art and furniture. Archaeologists have also found hundreds of regular homes and shops. Even things made of wood and human bodies were preserved in the ash. This allowed experts to make molds of people in their final moments.

After it was buried, Pompeii stayed hidden for a long time. It was rediscovered in the late 1500s, but serious digging didn't start until the mid-1700s. Today, Pompeii is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It's one of Italy's most popular places to visit, with millions of tourists each year.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name Pompeii comes from an ancient language called Oscan. The word pompe meant "five." Some people think this means the city was made up of five small villages. Others believe it might be linked to a powerful family called the Pompeia gens.

Where Was Pompeii?

Pompeii was built about 40 meters above sea level. It sat on a plateau made from old lava flows from Mount Vesuvius, which is about 8 kilometers away. The city was once right by the sea. Today, it's about 700 meters inland.

The Sarno River flowed next to the city. Its mouth was a safe harbor for early Greek and Phoenician sailors. Later, the Romans made it an important port. Pompeii covered an area of about 64 to 67 hectares. It was home to around 11,000 to 11,500 people.

A Look Back in Time

Pompeii has a long history, much older than the Roman city we see today. It grew a lot after 450 BC when the Greeks were in charge.

Early Beginnings

The first people to settle here were the Oscans, around the 8th century BC. They founded five small villages. When the Greeks arrived in the area around 740 BC, Pompeii became part of their world. A Greek-style temple was built, and the worship of Apollo began.

In the early 6th century BC, the villages joined together. They built a strong city wall made of volcanic rock called tufa. This wall was much bigger than the early town, showing that Pompeii was already important and rich. A small port was built, and trade by sea began.

Around 524 BC, the Etruscans took control of the area. They used the Sarno River for trade between the sea and inland areas. Pompeii became part of the Etruscan League of cities. During this time, a simple market square (a "forum") and the Temple of Apollo were built.

The Samnite Era

Around 424 BC, the Samnites, a group of people from central Italy, took over Pompeii. They brought their own building styles and made the town bigger.

Pompeii became an ally of Rome during the Samnite Wars. Even though the Samnites governed the city, it was now connected to Rome. The city walls were made even stronger in the early 3rd century BC.

After the Samnite Wars, Pompeii became a "socii" of Rome. This meant it was allied with Rome but kept its own language and government. During the Second Punic War, when Hannibal attacked Italy, Pompeii stayed loyal to Rome. The city continued to grow rich by trading wine and olive oil.

In the 2nd century BC, Pompeii became even wealthier as Rome expanded its empire. Many grand public and private buildings were constructed. These included The Large Theatre, the Temple of Jupiter, and the Stabian Baths.

Becoming Roman

Pompeii joined other towns in a rebellion against Rome in the Social Wars. In 89 BC, the Roman general Sulla attacked Pompeii. You can still see the marks of thousands of ballista shots on the city walls. Pompeii was forced to surrender and became a Roman colony called Colonia Cornelia Veneria Pompeianorum.

Many Roman soldiers were given land in Pompeii. The city quickly became Roman, with Latin as its main language. The area around Pompeii became very popular for wealthy Romans. Many farms and villas were built outside the city, like the famous Villa of the Mysteries.

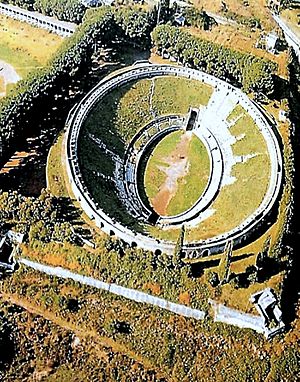

Pompeii became an important stop for goods traveling between the sea and Rome. New public buildings were built or improved, such as the Amphitheatre of Pompeii in 70 BC and the Forum Baths. These made Pompeii a cultural center in the region.

Around 30 BC, under Emperor Augustus, more new public buildings were added. These included the Eumachia Building and the Macellum. Around 20 BC, Pompeii got running water from the Serino Aqueduct.

In 59 AD, there was a big fight in the amphitheater between people from Pompeii and a nearby town called Nuceria. The Roman Senate had to send soldiers to stop it and banned events there for ten years.

Earthquakes and Rebuilding (62–79 AD)

People in Pompeii were used to small earthquakes. But on February 5, 62 AD, a very strong earthquake caused a lot of damage. It was probably between 5 and 6 on the Richter scale. Fires broke out, adding to the panic.

After the earthquake, people started rebuilding. Many private homes were repaired, and old wall paintings were covered with new ones. Public buildings were also improved. Some new, modern buildings, like the Central Baths, were even started after the earthquake. This shows that Pompeii was still a thriving city, not just struggling to recover.

By 79 AD, Pompeii had a population of about 20,000 people. It was a prosperous city thanks to its rich farmland and good location.

The Eruption of Vesuvius

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius lasted for two days. The first part was a rain of pumice (small volcanic rocks) that lasted about 18 hours. This gave most people time to escape. Only about 1,150 bodies have been found, suggesting many people got away. Many who escaped probably took their valuable belongings with them.

Later, fast-moving, super-hot clouds of ash and gas, called pyroclastic flows, rushed down the volcano. These clouds knocked down buildings and instantly killed anyone still there. By the end of the second day, the eruption was over.

Scientists now believe that the extreme heat from these pyroclastic flows was the main cause of death. Temperatures of at least 250°C (482°F) were enough to cause instant death, even inside buildings. Pompeii was buried under up to 6 meters (20 feet) of ash and volcanic material. Recent discoveries in 2023 showed that some buildings also collapsed during earthquakes that happened during the eruption.

Pliny the Younger wrote an important account of the eruption. He saw it from across the Bay of Naples. His uncle, Pliny the Elder, died trying to rescue people. Scientists call similar eruptions "Plinian" because of his detailed description.

For a long time, people thought the eruption happened in August. However, new evidence, like a charcoal inscription found in 2018, suggests it happened later. This inscription had the date October 17. Other clues, like people wearing warmer clothes, autumn fruits in shops, and wine being sealed, also point to an October or November eruption. A study in 2022 confirmed the date as October 24–25.

Rediscovery and Digging

After the eruption, survivors and even thieves came back to salvage valuables. They dug holes through walls to find marble statues and other precious items. The tops of some taller buildings were still visible, making it easier to find places to dig.

Archaeological evidence shows that a small settlement of survivors lived on the site until the fifth century. Over time, the city's name and exact location were forgotten. More eruptions covered the remains even deeper. The area became known as La Civita, meaning "the city," because of the ancient features in the ground.

In 1592, an architect named Domenico Fontana was digging an underground aqueduct. He accidentally found ancient walls with paintings and writings. He kept his discovery a secret.

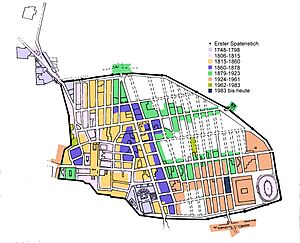

In 1738, the nearby city of Herculaneum was rediscovered. This led to more interest in finding other buried cities. In 1748, excavations began at Pompeii, though the city wasn't fully identified yet. On August 20, 1763, an inscription was found that clearly named the city as Pompeii.

Giuseppe Fiorelli took charge of the excavations in 1863. He made a huge discovery: he realized that the empty spaces in the ash were left by decomposed bodies. He developed a technique to pour plaster into these voids to create casts of Vesuvius's victims. This method is still used today, but with clear resin instead of plaster.

Fiorelli also organized the city into nine areas, called regiones, and blocks, called insulae. He numbered the entrances of individual houses. This made the excavations much more scientific.

Modern Archaeology

After Fiorelli, excavations continued, but sometimes the focus was more on finding spectacular items than on careful preservation. In the 1920s, Amedeo Maiuri dug deeper to learn about Pompeii's earlier history. He did large-scale excavations in the 1950s, uncovering much of the city.

Today, archaeologists focus more on preserving and documenting the ruins. Large new excavations are rare. In December 2018, the remains of harnessed horses were found in the Villa of the Mysteries.

The 'Great Pompeii Project' started in 2012. It helped stabilize over 2.5 kilometers of ancient walls. In November 2020, the remains of two men, possibly a rich man and his slave, were found. They seemed to have survived the first eruption but died in a second blast.

In December 2020, a thermopolium (an ancient snack bar) was excavated. It had colorful wall paintings of food, and archaeologists found pots with remnants of meals like duck, goat, and fish. They also found a tiny dog skeleton, showing that Romans bred small dogs.

In January 2021, a well-preserved ceremonial chariot was found in a luxurious villa. It's thought to be a special bridal carriage. In 2021, a painted tomb of a freed slave, Marcus Venerius Secundio, was discovered. It showed he organized Greek and Latin performances, which was new information about Pompeii's culture.

In April 2024, a dining hall with rare frescoes of Helen of Troy and Apollo was found. In June 2024, a shrine with blue-painted walls and paintings of the four seasons was discovered.

Keeping Pompeii Safe

Objects buried in Pompeii were preserved for almost 2,000 years because there was no air or moisture. But once excavated, they started to decay. Weather, erosion, light, water, and even tourists have caused damage. Two-thirds of the city has been uncovered, but the ruins are slowly deteriorating.

During World War II, some buildings were damaged by bombs. The World Monuments Fund has listed Pompeii as needing urgent repair. In 2010, the Schola Armatorum (House of the Gladiators) collapsed due to heavy rain and poor drainage.

Today, a lot of money is spent on conservation. In 2013, UNESCO warned that Pompeii could be put on the List of World Heritage in Danger if more progress wasn't made. The "Grande Progetto Pompei" project, with help from the European Union, has worked to stabilize and preserve buildings.

In 2020, many ancient gardens, orchards, and vineyards were carefully recreated. In 2021, several restored houses, like the House of the Ship Europa and the House of the Lovers, were reopened to the public.

Roman City Life

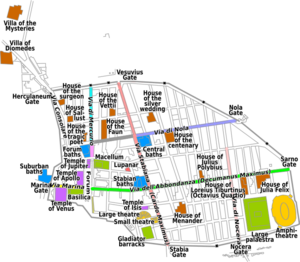

Pompeii is very important for studying Ancient Roman architecture and city planning. It was a smaller city compared to Rome, but it kept many of its older buildings from as early as the 4th century BC. By the time the Romans took over in 89 BC, most of the streets and city blocks were already built.

Public Spaces

Under Roman rule, Pompeii grew and developed. New public buildings included the Amphitheatre, which had a large open area for sports (a palaestra) and a swimming pool. There were also two theaters and at least four public baths. The amphitheater was well-designed to manage large crowds.

Other important buildings included the Macellum (a meat market), bakeries, and thermopolia (snack bars that served hot and cold food). An aqueduct brought fresh water to the public baths, over 25 street fountains, and many private homes.

Shops and Workshops

Pompeii had at least 31 bakeries, each with wood-burning ovens and millstones. The Modestus bakery was the largest in the city. There were nearly 100 thermopolia (snack bars). The thermopolium of Vetutius Placidus had a counter and large pots for food. It also had a dining room decorated with paintings.

Wool processing was a big industry. There were workshops for cleaning, spinning, dyeing, and washing wool. The Building of Eumachia was a wool market or a meeting place for wool workers. It had a jar near the entrance where urine was collected to use as a detergent for clothes.

A garum workshop made a popular fish sauce. Large containers with the sauce were found there.

Farming and Gardens

Pompeii had very fertile soil, perfect for growing crops. The land around Mount Vesuvius held water well, and sea breezes helped keep the soil moist. Farmers grew barley, wheat, and millet, along with grapes for wine and olives for oil. These products were exported to other regions.

Wine was especially important to Pompeii's economy. Ancient Roman rules said that vineyards had to produce a certain amount of wine. Pompeii's rich lands often produced much more than required, encouraging local wineries to grow.

Archaeologists have found carbonized remains of plants, roots, seeds, and pollen in Pompeii's gardens. These show that people ate wheat, millet, walnuts, pine nuts, chestnuts, hazelnuts, chickpeas, broad beans, olives, figs, pears, onions, garlic, peaches, grapes, and dates. Most of these could be grown locally.

Ancient Artworks

The discovery of certain types of artwork in Pompeii presented a challenge for early archaeologists. The way people viewed art and private life in ancient Rome was very different from the views in Europe during the 1700s and 1800s.

Some discoveries were hidden away. For example, a wall painting of an ancient god was covered with plaster. Many artifacts from Pompeii are now kept in the Naples National Archaeological Museum. In 1819, a king visiting the museum was so uncomfortable with some of the artwork that he had it locked away in a "secret cabinet." This special gallery was only open to "people of mature age and respected morals." The "Secret Museum" was closed and reopened several times over the years. It was finally reopened for public viewing in 2000. Today, younger visitors are allowed in with an adult or written permission.

Visiting Pompeii

Pompeii has been a popular tourist spot for over 250 years. It attracts almost 2.6 million visitors each year, making it one of Italy's most visited sites. It's part of a larger Vesuvius National Park and was named a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1997.

To help manage the large number of visitors, new tickets allow tourists to visit other nearby ancient cities like Herculaneum and Stabiae. This helps spread out the crowds and reduces pressure on Pompeii itself. In 2024, the site announced it would limit daily ticket sales to 20,000 and introduce timed entry during busy summer months.

The nearby modern town of Pompei relies heavily on tourism. Many local residents work in hotels, restaurants, or as taxi drivers, serving the visitors to the ancient city.

New large-scale excavations were stopped in 1999 but resumed in 2017. Today, fewer buildings are open to tourists than in the past, as the focus is on preserving the existing ruins.

The Pompeii Museum

The Antiquarium of Pompeii is a museum that was first built in the 1870s. It shows archaeological finds that help us understand daily life in the ancient city. The building was damaged during World War II bombings and by an earthquake in 1980.

After being closed for 36 years, the museum reopened in 2016 for temporary exhibitions. On January 25, 2021, it reopened as a permanent museum. Visitors can now see discoveries from the excavations, plaster casts of the eruption victims, and learn about Pompeii's history before it became a Roman city.

Documentaries

- In Search of... episode No. 82 focuses on Pompeii; it first aired on November 29, 1979.

- The National Geographic special In the Shadow of Vesuvius (1987) explores Pompeii and Herculaneum.

- Ancient Mysteries: Pompeii: Buried Alive (1996), an A&E documentary.

- Pompeii: The Last Day (2003), a drama from the BBC that shows the last hours of people living in Pompeii.

- Pompeii and the AD 79 eruption (2004), a two-hour Tokyo Broadcasting System documentary.

- Pompeii Live (June 28, 2006), a Channel 5 show with a live archaeological dig.

- Pompeii: The Mystery of the People Frozen in Time (2013), a BBC One documentary.

- The Riddle of Pompeii (May 23, 2014), Discovery Channel.

- Pompeii: The Dead Speak (August 8, 2016), Smithsonian Channel.

- Pompeii's People (September 3, 2017), a CBC Gem documentary.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Pompeya para niños

In Spanish: Pompeya para niños

- Foreign influences on Pompeii

- Mastroberardino, a project to replant Pompeii's vineyards

- Robert Rive, a photographer of Pompeii in the 1850s

- Luigi Bazzani: Watercolours of Pompeii when first excavated

- Other cities buried by volcanoes

- Armero tragedy, a city in Colombia buried in 1985

- Akrotiri, in Greece, an ancient city buried over 3000 years ago

- Joya de Cerén, a village in El Salvador known as the "Pompeii of the Americas"

- Plymouth, Montserrat, a capital city buried by volcanic ash in the 1990s

- Saint-Pierre, Martinique, a town destroyed by a volcanic eruption in 1902

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |