Pipe organ facts for kids

The pipe organ is a big keyboard instrument. It makes sound when air blows through its many pipes. A person who plays the organ is called an organist. Organists use both their hands and feet to play. Their hands play the keyboards, which are called "manuals." Their feet play special pedals that also make musical notes.

Organs have been around for many centuries. You usually find them in churches and cathedrals for Christian worship. But they can also be in town halls, concert halls, or even large private houses. Small organs are sometimes called "chamber organs." Organs in big churches are huge instruments. They are built especially for the building they are in. They are called "pipe organs" to tell them apart from modern electronic organs.

No two pipe organs are exactly the same. They look and sound very different depending on the country and the time period they were built. This article focuses on organs from Europe, Great Britain, and America.

Contents

What is a Pipe Organ Made Of?

A pipe organ makes music by blowing air through its pipes. Every organ needs three main things: pipes, a way to blow air, and a way to control which pipes play.

The pipes are made of metal or wood. They stand in rows inside the "organ case," which can be as big as a room. Metal pipes are round tubes. They are often made from an alloy (a mix of metals) of tin and lead. This mix is called "spotted metal" because it has shiny spots. This metal helps pipes sound clear and warm. Very small pipes can be made of silver, like flutes. Some organs also have brass pipes that sound like trumpets. Many organs have wooden pipes too. Wooden pipes have four flat sides and sound different from metal pipes. They are usually hidden behind the large, decorated metal pipes at the front. All pipes have a tapered end where the air blows in.

Each pipe plays only one note. The size of the pipe decides its note. Small pipes play high notes, and large pipes play low notes. Each pipe also has its own special sound. This sound depends on what it's made from (wood, brass, or spotted metal) and its shape. Pipes are grouped into "ranks." All pipes in a rank have the same shape and material. This allows the organist to choose which groups of pipes play together.

To blow air through the organ, there are big boxes called "wind chests." When the organist plays, a small gauge shows if there's enough air. In the past, huge "bellows" were pumped up and down by a person to fill the wind chests. This was very hard work! Today, most organs use an electric motor and a large fan to fill the wind chests with air.

How Does an Organist Play?

Organists use keyboards, like those on a piano. A small organ might have one keyboard. Many organs have two, and very big ones can have five. Organists call these keyboards "manuals." So, a "four-manual organ" is a very large one. The manuals are part of the "organ console." The organist sits on a bench in front of the console to play.

Besides the manuals, there are two other important parts. There are long wooden pedals that the organist plays with their feet. Each pedal plays a different note.

On both sides of the manuals, there are rows of "stops." These look like small knobs. When a stop is pulled out, it turns on certain sets of pipes. The organist can choose loud pipes or soft pipes. They can choose pipes that sound like flutes, trumpets, or sweet, gentle sounds. As the organist plays, they don't just think about the notes. They also think about the "voice" or sound the organ should make. They can play different ranks of pipes together by pulling out several stops. The biggest, most decorated pipes at the front are often used for the grandest music. These pipes are sometimes seen as a symbol of the "Voice of God."

When the organist presses a key, air blows through a pipe. This happens because a valve opens to let air into that pipe. The valve closes when the key is released. This can happen in different ways. Older organs use "tracker action." This means thin wooden rods and wires (trackers) move back and forth to open and close the valves. These are connected to levers under the keyboard. A tracker organ's console must be very close to the pipes.

More modern organs use "tubular pneumatic" action. Here, the console can be further away. Air is pushed through tubes to open the valves. The most modern pipe organs use electric wires. Electro-magnetic switches control the power to open and close the valves. This allows the console to be placed anywhere. This helps the organist connect better with the people in the church or with other musicians.

Parts of the Organ Console

Manuals: The Keyboards You Play

A very small organ might have just one manual (keyboard). Most organs have at least two. In English and American organs, the bottom manual is the main one. It is called the Great. The manual above it is called the Swell. This is because its pipes are inside a "swell box" with shutters. These shutters can open or close, making the music louder or quieter. The organist controls the swell box with a foot pedal.

If there is a third manual, it's usually called the Choir in English-speaking countries. This manual often has soft sounds, good for accompanying a choir. In German organs, the third manual was called the “Positiv.” Sometimes it was a “Rückpositiv,” meaning the pipes were behind the organist.

A fourth manual is called the Solo. Its stops are used to play a tune loudly, like a solo instrument. This manual is even farther away from the player than the Swell. Large cathedral organs often have four manuals. The Solo manual might have a very loud stop called the “Tuba” or “Tuba Mirabilis.”

If there is a fifth manual, it might be called the Echo. This manual has very quiet stops that create an echo effect. Or, especially in American organs, it might be a Bombarde. The Bombarde usually has loud, strong reed stops. These stops can be heard above all the other sounds. Having a Bombarde Manual is a special feature for an organist. You can find one, for example, on the organ of Westminster Abbey.

It's very rare to have more than five manuals. But in America, there are a few huge organs. The Wanamaker organ in Macy's store in Philadelphia has six manuals. The world’s largest organ is in the Atlantic City Convention Hall. It has seven manuals and over 33,000 pipes! However, this organ doesn't work because it would be too expensive to run.

Playing with Multiple Manuals

Having two or three manuals allows for quick changes in sound during a piece. The player can also use both hands on different manuals at the same time. This is helpful for making a tune louder than its accompaniment. (On a piano, you can do this by pressing harder.)

Manuals can also be "coupled" together. For example, pulling out the “Swell to Great” stop makes all the sounds from the Swell manual also play on the Great manual. On organs with mechanical action, you might see the keys of the Swell manual move by themselves. On some older organs, coupling manuals can make the keys very heavy to press.

Pedals: Playing with Your Feet

The notes on the pedals are arranged like a keyboard, but they are much bigger. Organists learn to play by "feel" so they don't have to look at their feet. They play each note with their toe or heel, and with the inside or outside of their foot. American and British organs usually have 30 notes, covering almost 2 ½ octaves. The pedals are not quite in a straight line. They fan out a little to make them easier to play. This is called a "radiating, concave pedalboard." In German and French organs, and organs built before 1920, the pedalboard is straight. Many organists find this harder to play.

Organists need special shoes. They should have narrow heels and pointed toes. The soles should be a bit slippery, but not too much. This helps the player slide their foot from one pedal to another. Organists often keep a pair of shoes just for playing the organ. This keeps dirt from the street off the pedals.

Stops: Choosing Your Sounds

The stops on an organ console create different sounds, like the instruments in an orchestra. Their names tell the organist what kind of sound they will make. Stops are usually on the left and right of the organist. They are pulled out ("drawstops" or "pulls") to turn them on. Some organs have "tab stops" or "rocker stops" in front of the player. These can be rocked back and forth to turn them on or off.

Organ stops can be grouped into families:

- The chorus stops are the basic, strong sounds. They are good for building a big, solid sound. A diapason or principal is a chorus stop.

- The flute stops sound like flutes in an orchestra. They are softer than diapasons and good for quick, light music.

- The reeds are stops like the oboe, clarinet, trumpet, fagotto, and trombone. Each pipe has a reed inside. Their sound is very strong and can be a bit "nasal."

- The strings are quiet stops that sound like string instruments. Examples are the violone and gamba.

Another way to group stops is by their number. Each stop has a number under its name, like 16, 8, 4, 2, 1, or even 2 2/3 or 1 3/5. If the number is 8, it's an "eight-foot stop." This is the normal pitch. The note sounds as it's written. For example, if you play Middle C, you hear Middle C. A 4-foot stop sounds an octave higher than written. A 2-foot stop sounds two octaves higher. A 16-foot stop sounds an octave lower than an 8-foot stop. So, 8-foot is the normal pitch. Other stops are added to make the sound bigger and brighter. 16-foot stops are common for pedal parts.

Mutation stops are special. Their notes don't sound a whole number of octaves above the normal pitch. For example, the Tierce 1 3/5 sounds two octaves and a third higher. The Nazard or Twelfth 2 2/3 sounds one octave and a fifth higher.

Choosing Stop Combinations

An organist needs to learn which combinations of stops sound good together. They also need to know how to balance them. Every organ is different and has its own unique sound.

The combination of stops an organist chooses for a piece of music is called the “registration.” The list of all the stops an organ has is called the “specification.” This list shows the names of stops for each manual and for the pedals, plus any couplers.

Organs also have buttons called “pistons.” These help change the registration quickly during a piece. “Toe pistons” are operated by the feet. “Thumb pistons” are placed just below each manual. The organist can push them with their thumb while their fingers keep playing. Large organs often have “general pistons” that change many stops across the organ at once. These can be set up by a computer. This lets players create their own personal settings for the pistons. If several players use the organ, they can lock their settings so no one else can change them.

More About the Pipes

Each stop controls a row of pipes, called a “rank.” Each rank makes a different sound. For example, one rank for the “diapason” sound, another for the “flute,” and another for the “trumpet.” Some stops control more than one rank. For instance, a Mixture stop might have three ranks of pipes. The Celeste stop often has two ranks. The pipes in one Celeste rank are tuned slightly sharper than the other. When played together, they create a pleasant, throbbing sound.

Organ pipes are usually made of metal or wood. High-quality metal pipes often have 75 percent tin or more, with the rest being lead. The pipes sit on windchests inside an "organ case." A windchest is a box with "pallets" (small doors). These pallets open and close to let air into a pipe so it can sound. In older organs, pull wires and rollers operate the pallets. In modern organs, they might use air pressure or magnets.

Air is always pumped into the windchest when the organ is on. Before electricity, a person called an "organ blower" had to pump air into the windchest using bellows. This was very hard work! Large organs needed more than one person for this job.

The History of the Pipe Organ

The organ has changed and grown in many ways over time. For example, if the famous composer Bach (who lived in the early 18th century in Germany) had visited France, he would have found it hard to play his music on French organs. French organs were very different. Organists today need to know a lot about organs from different countries and times. This helps them choose the right sounds when playing old music.

Early Organs

The very first organs were water organs. They were invented in Ancient Greece. The Romans used them in circuses because they were very loud. Water organs were still popular in some places a few hundred years ago, like in pleasure gardens.

Organs in the Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, large organs were built in huge Gothic cathedrals in Britain. These early organs didn't have different stops. All the pipes sounded at once! They were played using a sliding mechanism. Keyboards started to be used in the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries. Small organs called portatives could be carried and were used in processions. Positives were a bit bigger and used to accompany singing in church. The Regal was like a portative but had reeds and no pipes. It could sit on a table. The world's oldest working organ is thought to be one built in Sion, Switzerland in the 15th century.

Organs in the Renaissance (around 1450-1600)

By about 1450, organs in Germany and the Netherlands had two or three manuals and pedals. They also had stops, so players could choose which pipes to sound. The Buxheimer Orgelbuch (around 1470) is one of the first collections of organ music we have. French organs were also developing. In England, organs were quite small. Composers like John Bull wrote music for chamber organs.

Organs in the Baroque Period (around 1600-1750)

The Baroque period was a great time for organ music in Germany. Organs were built with the Werkprinzip (meaning "work principle"). This meant each keyboard and its pipes were built separately, almost like different organs, but played from one console. Famous organ builders like Arp Schnitger (1648-1719) built these. Many German composers wrote organ music, including Johann Pachelbel (1653-1709) and Dietrich Buxtehude (1637-1707). The great composer Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) learned from them. He wrote some of the most famous organ music ever. The organ builder Gottfried Silbermann (1683-1753) built organs with a beautiful sound.

French organ builders at this time loved different sound "colors." Many stops had names like Cornet and Tierce. When all the main chorus stops played together, it was called the Plein jeux. All the reed stops together were called Grand jeux. This sounded very loud and was used for dialogues and fugues. Composers included Louis-Nicolas Clérambault (1676-1749) and François Couperin (1683-1733).

In England, organs were not developed much. They were mostly used to accompany choirs. They didn't have pedals. Organ pieces were called voluntaries. Henry Purcell wrote a few organ pieces.

Organs in the Classical Period (around 1750-1840)

After J.S. Bach, people became less interested in organ music. Not many new things happened in organ building during the Classical music period. Even though Mozart played the organ and called it the “King of Instruments,” he didn't write much music for it.

Organs in the Romantic Period

In 19th century Germany, organs started to sound more like an orchestra. People also became interested in playing J.S. Bach's music again. Many older organs were rebuilt, sometimes losing their original sound. Organs in different countries began to sound more alike.

Composers started writing for the organ again. Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) wrote excellent sonatas and preludes. These were inspired by Bach and encouraged others to write organ music. Later, Max Reger (1873-1916) and Sigfrid Karg-Elert (1877-1933) wrote for the organ.

In France, the organ builder Aristide Cavaillé-Coll (1811-1899) was a true genius. His organs had many new ideas. Organists could change their sounds quickly. Composers like César Franck (1822-1890), Charles-Marie Widor (1845-1937), and Louis Vierne (1870-1937) wrote long pieces called Symphonies. These pieces were full of colorful sounds, like a symphony orchestra.

In England, Samuel Wesley (1766-1837) wrote important organ music inspired by Bach. His son, Samuel Sebastian Wesley (1810-1876), was influenced by European Romantic composers. In 1851, the builder Henry Willis built a large organ for the Crystal Palace Exhibition. It had three manuals and a pedal board. This organ set the standard for English organ building.

The Organ in the Twentieth Century

During the 20th century, organ builders became more interested in older Baroque and Classical ideas. Many organs now use electric action. However, a good mechanical action makes the player feel more connected to the instrument. Some large 20th-century organs can play many kinds of organ music. Other organs were built to copy Baroque or Classical instruments. These are best for older music, not for music from the 19th and 20th centuries.

In the 19th century, many organs in England and America were placed in church corners where they couldn't be heard well. In the 20th century, builders thought more about the best place for the organ. They wanted the sound to fill the main part of the church, the nave.

Famous 20th-century organ composers include Marcel Dupré (1886-1971) and Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) from France. Paul Hindemith (1895-1963) was from Germany. From England came Edward Elgar (1857-1934) and Herbert Howells (1892-1983). The Czech composer Petr Eben (1929-2007) was very important at the end of the 20th century. He wrote in his own special style.

The Organ as an Accompanying Instrument

Organs are often used to accompany church choirs and congregational singing. But they also accompany other instruments. In the Baroque period, small organs were used with solo instruments, small groups, or orchestras. This kind of accompaniment was called continuo.

Sometimes, composers write organ concertos. In these, the organ is the main solo instrument, and the orchestra plays along. Handel wrote several of these. In modern times, Francis Poulenc wrote an organ concerto. There is also an important organ solo in Symphony No. 3 by Saint-Saëns. Other orchestral works sometimes have organ parts. Organists often arrange music written for other instruments so it can be played on the organ. These are called "transcriptions."

Related pages

Images for kids

-

Hydraulis from the 1st century BC, oldest organ found to date, Museum of Dion, Greece

-

4th century AD "Mosaic of the Female Musicians" from a Byzantine villa in Maryamin, Syria.

-

9th century image of an organ, from the Utrecht Psalter.

-

The baroque organ in Roskilde Cathedral, Denmark

-

Baroque pipe organ of the 18th century at Monastery of Santa Cruz, Coimbra, Portugal

-

The pipe organ in the chapel of San Carlos Seminary, Makati, Philippines exhibits a modern façade.

-

The Salt Lake Tabernacle organ found at the Salt Lake Tabernacle in Salt Lake City, Utah has 11,623 pipes and accompanies the Mormon Tabernacle Choir and Orchestra at Temple Square.

-

Interior of the Seville Cathedral, showing the pipes of the organ.

-

Pipes of the organ of the Comayagua Cathedral in Honduras.

-

The organ of the Severikirche in Erfurt, Thuringia, Germany has a highly decorative case with ornate carvings and cherubs.

-

A typical modern 20th-century console, located in St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin

-

The organ of the Cathedral-Basilica of Saint-Denis (France), first organ of Aristide Cavaille-Coll containing numerous innovations, and especially the first Barker lever.

-

Cross-section of one note of a mechanical-action windchest. Trackers attach to the wires hanging through the bottom board at the left. A wire pulls down on the pallet (valve) against the tension of the V-shaped spring. Wind under pressure surrounds the pallet, and when it is pulled down, the wide rectangular chamber above the pallet feeds wind to all pipes of this note and stop; note the cutaway passages at the top.

-

Interior of the organ at Cradley Heath Baptist Church showing the tracker action. The black rods, called rollers, rotate to transmit movement sideways to line up with the pipes.

-

Saint Cecilia, patron saint of music, depicted playing the pipe organ

-

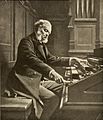

The organ music of Johann Sebastian Bach (by Haussmann, c. 1748) forms an important part of the instrument's repertoire.

-

César Franck (by Rongier, 1888) at the console of the organ at Saint Clotilde, Paris

-

Camille Saint-Saëns (by Nadar) famously included a prominent organ part in his Symphony No. 3, which is thus sometimes known as the Organ Symphony

-

The composer Olivier Messiaen (1986) championed an innovative and unprecedented approach to organ music

See also

In Spanish: Órgano (instrumento musical) para niños

In Spanish: Órgano (instrumento musical) para niños