Jan van Eyck facts for kids

Jan van Eyck (born before 1395 – died before July 9, 1441) was a famous painter from the Netherlands. He worked in Bruges and is known as one of the best Northern European painters of the 1400s.

Many people used to think Jan van Eyck invented oil painting. This idea started a long time ago, in the 1500s. While he didn't invent it, he was incredibly skilled at using oil paints. He found new and amazing ways to make his paintings look real and detailed. Because of his great skill, he is often called the "father of oil painting." He loved art from a young age, and his older brother, Hubert, encouraged him.

Jan van Eyck passed away in Bruges in 1441. He was buried in the Church of St Donatian, which was later destroyed.

Contents

Life and Career

Early Years

We don't know much about Jan van Eyck's early life, like exactly when or where he was born. The first official record of him is from 1422 to 1424. He was working for John of Bavaria in The Hague as a court painter. This means he was likely born by 1395 at the latest. However, some experts think he looked older in his 1433 self-portrait, suggesting he might have been born closer to 1380.

Jan had a sister named Margareta and at least two brothers, Hubert (who died in 1426) and Lambert (who worked between 1431 and 1442). Both of his brothers were also painters. Jan likely learned his skills from Hubert. We don't know where Jan went to school, but he knew Latin and used Greek and Hebrew letters in his art. This shows he had a good education, which was unusual for painters back then.

Working for the Duke

Van Eyck worked for John of Bavaria-Straubing, who ruled areas like Holland. During this time, he had his own small art studio and helped decorate the Binnenhof palace. After John's death in 1425, Jan moved to Bruges. There, he caught the attention of Philip the Good, the Duke of Burgundy, around 1425.

Becoming the Duke's painter made him very famous. His work for the court is well-documented. He was both a court artist and a diplomat. He was also an important member of the Tournai painters' guild. In 1427, he attended a special dinner in his honor in Tournai, where other famous painters like Robert Campin and Rogier van der Weyden were also present.

Being paid by the Duke meant Jan didn't have to rely on other jobs. This gave him a lot of freedom in his art. Over the next ten years, van Eyck's fame and painting skills grew. He was especially good at new ways of using and mixing oil paints. Unlike many artists, his reputation never faded. His new approach to oil painting was so amazing that people started the myth that he invented it.

His brother Hubert van Eyck helped him with his most famous work, the Ghent Altarpiece. Art experts believe Hubert started it around 1420, and Jan finished it in 1432. Another brother, Lambert, might have managed Jan's workshop after Jan died.

Success and Later Life

Jan van Eyck's art was seen as groundbreaking during his lifetime. His ideas and methods were widely copied. His personal motto, ALS ICH KAN ("AS I CAN"), was one of the first and most unique signatures in art history. It was a clever play on his name. This motto first appeared in 1433 on his Portrait of a Man in a Turban, showing his growing confidence. The years between 1434 and 1436 were his peak. During this time, he created famous works like the Madonna of Chancellor Rolin and Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele.

Around 1432, he married Margaret, who was 15 years younger than him. About the same time, he bought a house in Bruges. Margaret is first mentioned when their first child was born in 1434. We don't know much about Margaret, not even her last name. She might have come from a noble family, though not the highest rank. Her clothes in her portrait are stylish but not as fancy as those in the Arnolfini Portrait. After Jan's death, the city of Bruges gave Margaret a small pension as a sign of respect for her famous husband.

Van Eyck went on several "secret" trips for Duke Philip between 1426 and 1429. He was paid a lot for these trips, which suggests he was acting as a special messenger for the Duke. We don't know exactly what these missions were. One well-known trip was to Lisbon. He went with a group to prepare for the Duke's wedding to Isabella of Portugal. Van Eyck's job was to paint the bride so the Duke could see her before they married. He spent nine months there. The princess was probably not very pretty, and van Eyck painted her exactly as she was. He usually showed people with dignity but didn't hide their flaws. After returning, he finished the Ghent Altarpiece, which was officially shown in 1432. Records from 1437 show he was highly respected by the Duke's court and worked on projects for other countries.

Death and Lasting Impact

Jan van Eyck died on July 9, 1441, in Bruges. He was buried in the churchyard of St Donatian's Cathedral. As a sign of respect, Duke Philip gave Jan's widow, Margaret, a payment equal to his yearly salary. Jan left many unfinished paintings, which his workshop assistants completed. After his death, his brother Lambert van Eyck likely took over the workshop. Jan's fame continued to grow. In early 1442, Lambert had Jan's body moved inside St. Donatian's Cathedral.

In 1449, an Italian writer named Ciriaco de' Pizzicolli mentioned him as a very skilled painter. Another writer, Bartolomeo Facio, also praised him in 1456.

Works

Jan van Eyck painted for private clients as well as for the court. His most famous work is the Ghent Altarpiece. He painted it for a wealthy merchant and politician named Jodocus Vijdts and his wife. Started before 1426 and finished by 1432, this large painting is seen as a masterpiece. It shows a new level of realism in Northern Europe, different from the art of the Early Renaissance in Italy.

He probably painted many three-part paintings called triptychs, but only the Dresden altarpiece still exists. About 20 of his paintings are still around today, all made between 1432 and 1439. Ten of these, including the Ghent Altarpiece, are signed with his motto, ALS ICH KAN.

Turin-Milan Hours: Hand G

Since 1901, many people believe Jan van Eyck was the unknown artist called "Hand G" who worked on the Turin-Milan Hours. This was a very detailed book of prayers. If this is true, these illustrations are the only known works from his early career. Some experts think these early works might have influenced his later oil paintings.

The reason for thinking van Eyck was Hand G is that some figures in the book look like those in his later paintings. Also, there are family symbols connected to people he knew in The Hague. Sadly, most of the Turin-Milan Hours were destroyed in a fire in 1904. Only a few pages believed to be by Hand G still exist.

Paintings of Mary

Besides the Ghent Altarpiece, most of Van Eyck's religious paintings feature the Virgin Mary as the main figure. She is usually shown sitting, wearing a crown, and holding a playful baby Jesus. Jesus often looks at her and grabs her dress, similar to old Byzantine paintings. Sometimes she is shown reading a prayer book. She usually wears red. In the 1432 Ghent Altarpiece, Mary wears a crown with flowers and stars. She looks like a bride and reads from a book.

Van Eyck often shows Mary appearing to a person kneeling in prayer. This idea of a saint appearing to an ordinary person was common in paintings of that time. In Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele (1434–1436), the Canon seems to be pausing from reading his Bible as Mary and Jesus, with two saints, appear before him.

Mary's importance in his art reflects how much people honored her in the 1400s. People believed Mary could help them reach heaven. Prayer was a way to spend less time in purgatory, a place where souls were purified before heaven. Wealthy people would pay for new churches or special paintings to show their devotion.

Van Eyck usually gives Mary three roles: Mother of Christ, a symbol of the Church, or Queen of Heaven. In his later paintings, Mary often represents the Church itself. In Madonna in the Church, she is so large that her head is almost as high as the church's gallery. This makes her seem like she is the church. This way of changing size is also seen in his Annunciation. Her huge size comes from older Italian artists and shows her connection to the church building.

Van Eyck's later works have very detailed architectural backgrounds. However, these are not real buildings. He probably wanted to create a perfect, ideal space for Mary to appear.

His paintings of Mary are known for their complex use of space and light. Many of his religious works have small indoor spaces that still feel cozy and not cramped. The Madonna of Chancellor Rolin is lit from both the main doorway and side windows. The details in Madonna in the Church are so precise that many experts think he knew a lot about architecture. But in all his works, the buildings are imagined and perfect versions of what he thought a church should be.

His Marian paintings are full of writing. The words on the arch above Mary in the Ghent Altarpiece are from the Bible. Words from the same source are on her robe in Madonna in the Church. These writings are common in all his paintings, but especially in his Mary paintings. They make the portraits feel alive and give a voice to those praying to Mary. Since these paintings were for private prayer, the words might have been meant to be read as special prayers.

Portraits of People

Van Eyck was very popular for his portraits. As people in Northern Europe became wealthier, portraits were no longer just for kings and queens. A new middle class of merchants wanted portraits, and new ideas about individual identity also increased demand.

Van Eyck's portraits are known for his amazing use of oil paint and his careful attention to detail. He was very observant and used thin, see-through layers of paint to create rich colors and tones. He was a pioneer in portrait painting in the 1430s. People as far away as Italy admired how natural his portraits looked. Today, nine of his three-quarters view portraits are known. His style was copied by many, especially by van der Weyden and Petrus Christus.

The small Portrait of a Man with a Blue Chaperon from around 1430 is his oldest surviving portrait. It shows many features that became typical of his style. These include the three-quarters view (where the person is turned slightly), light coming from one direction, fancy headwear, and a simple, dark background. The portrait is known for its realism and sharp details, like the man's light beard. Van Eyck often showed men with a bit of stubble.

Notes he made for his drawing of Portrait of Cardinal Niccolò Albergati show how carefully he painted faces. He wrote about the beard, "the stubble of the beard grizzled." He also noted details about the eye, like "the iris of the eye, near the back of the pupil, brownish yellow."

The Léal Souvenir portrait from 1432 also shows his focus on realism and small details. However, in his later works, the person is shown from a bit further away, and the details are less sharp. Even in his early works, he didn't just copy exactly what he saw. He sometimes changed parts of a person's face or body to make the painting look better or more ideal. For example, in his wife's portrait, he changed the angle of her nose and gave her a fashionable high forehead that she didn't naturally have.

The stone ledge at the bottom of Léal Souvenir looks like real carved stone and has three layers of writing, making it seem like they are carved into the stone. Van Eyck often wrote inscriptions as if the person in the portrait was speaking. For example, the Portrait of Jan de Leeuw says, "...Jan de [Leeuw], who first opened his eyes on the Feast of St Ursula [October 21], 1401. Now Jan van Eyck has painted me, you can see when he began it. 1436." In Portrait of Margaret van Eyck from 1439, the writing says, "My husband Johannes completed me in the year 1439 on 17 June, at the age of 33. As I can."

Hands are important in van Eyck's paintings. In his early portraits, people often hold objects that show their job. The man in Léal Souvenir might have been a lawyer because he holds a scroll that looks like a legal document.

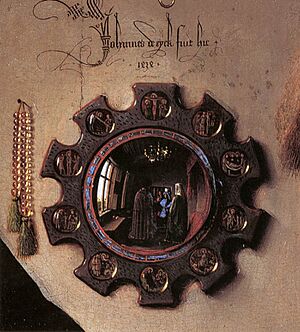

The Arnolfini Portrait from 1432 is full of clever illusions and symbols. So is the 1435 Madonna of Chancellor Rolin, which was painted to show Rolin's power, influence, and religious devotion.

Style

Hidden Meanings

Van Eyck included many symbolic elements in his paintings. These symbols often showed how he believed the spiritual and real worlds existed together. The symbols were hidden in the artwork, usually as small but important background details. His use of symbols and Bible references is a key part of his style. He was a pioneer in this, and other artists like van der Weyden copied his ideas. These artists used rich and complex symbols to show the strong beliefs of their time.

Experts say that van Eyck's mix of realism and symbolism is "the most important aspect of early Flemish art." The hidden symbols were meant to blend into the scenes and create a feeling of spiritual discovery. Van Eyck's religious paintings always show a special, transformed view of reality. For him, everyday life was filled with symbols. He arranged details to show not just earthly life but also what he believed was heavenly truth. This mix of earthly and heavenly shows van Eyck's belief that Christian teachings could be found in the "marriage of secular and sacred worlds." He painted very large Madonnas, whose unrealistic size showed the difference between heaven and earth. But he placed them in everyday settings like churches or homes.

Even the earthly churches in his paintings are heavily decorated with heavenly symbols. A heavenly throne is clearly shown in some home settings, like in the Lucca Madonna. It's harder to tell the setting for paintings like Madonna of Chancellor Rolin, where the place is a mix of earthly and heavenly. Van Eyck's symbols are often so layered that you need to look at a painting many times to understand even the most obvious meaning. The symbols were often subtly woven into the paintings, only becoming clear after careful and repeated viewing. Many of the symbols show the idea that there is a "promised passage from sin and death to salvation and rebirth."

His Signature

Jan van Eyck was the only painter in the 1400s Netherlands who regularly signed his artworks. His motto always included variations of ALS ICH KAN ("As I Can" or "As Best I Can"). This was a clever play on his name. The word Kan comes from a Dutch word related to "art."

This motto might be a humble way of saying he did his best, which was common in old writings. However, given how fancy his signatures often were, it might also be a playful reference. Sometimes, his motto looks like Christ's monogram. Also, since his signature often says "I, Jan van Eyck was here," it can be seen as a proud statement about how true and good his work was.

Because he signed his work, his fame lasted, and it's easier to know which paintings are his compared to other early Dutch artists. His signatures are usually written in a decorative style, like those used for legal documents. This can be seen in Léal Souvenir and the Arnolfini Portrait, which is signed "Johannes de eyck fuit hic 1434" ("Jan van Eyck was here 1434"). This was his way of recording his presence.

Writing in His Art

Many of van Eyck's paintings have a lot of writing on them, in Greek, Latin, or Dutch. Experts believe van Eyck himself painted these words. The writing seems to have different purposes depending on the type of painting. In his single portraits, the words give a voice to the person in the painting. For example, in Portrait of Margaret van Eyck, the Greek writing on the frame translates to "My husband Johannes completed me in the year 1439 on 17 June, at the age of 33. As I can."

However, the writing on his larger, public religious paintings is from the point of view of the person who paid for the painting. These words highlight their religious devotion and generosity. This can be seen in his Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele. An inscription on the bottom frame says, "Joris van der Paele, canon of this church, had this work made by painter Jan van Eyck. And he founded two chaplaincies here in the choir of the Lord. 1434. He only completed it in 1436, however."

Frames

Unusually for his time, van Eyck often signed and dated his frames. Back then, the frame was considered a key part of the artwork. The painting and frame were often made together. Even though different craftspeople made the frames, their work was seen as just as skilled as the painter's.

He designed and painted the frames for his single portraits to look like fake stone. The signature or other writing looked like it was carved into the stone. The frames also created other illusions. In Portrait of Isabella of Portugal, her eyes look out from the painting, and her hands rest on a fake stone ledge. This makes it seem like Isabella is reaching out of the painting towards the viewer.

Many of his original frames are now lost. We only know about them from copies or old records. The London Portrait of a Man was probably half of a two-part portrait. The last record of its original frames showed many inscriptions, but not all were original. Frames were often repainted by later artists. The Portrait of Jan de Leeuw still has its original frame, which is painted to look like bronze.

Many of his frames have a lot of writing. This serves two purposes: they are decorative, but they also explain the meaning of the artwork, similar to the margins in old books. Paintings like the Dresden Triptych were usually made for private prayer. Van Eyck would have expected the viewer to think about both the words and the images at the same time. The inside panels of the small 1437 Dresden Triptych have two layers of painted bronze frames with Latin writing. The texts come from different sources, including Bible descriptions of Mary's assumption and prayers to saints Michael and Catherine.

Workshop and Lost Works

Members of Jan van Eyck's workshop finished paintings based on his designs after he died in 1441. This was a common practice; a master's widow often continued the business. It's thought that either his wife Margaret or his brother Lambert took over after 1441. Examples of these works include the Ince Hall Madonna and Saint Jerome in His Study. Other famous artists, like Petrus Christus, also copied his designs.

His workshop also completed paintings that Jan left unfinished. The upper parts of the Crucifixion and Last Judgement diptych are believed to be the work of a less skilled painter. It's thought that van Eyck died before finishing this panel, but he had already drawn the outlines. His workshop members or followers then completed the upper area.

Three works are definitely believed to be by him, but we only know them from copies. The Portrait of Isabella of Portugal comes from his 1428 trip to Portugal. From the copies, we know it had two painted frames in addition to the real wooden frame. One had Gothic writing at the top, and a fake stone ledge supported her hands.

Two copies of his Woman Bathing were made within 60 years after his death. We mostly know about it because it appears in a 1628 painting by Willem van Haecht called The Gallery of Cornelis van der Geest. This painting shows a collector's gallery with many famous old artworks. Woman Bathing has many similarities to the Arnolfini Portrait, like an indoor scene with a bed, a small dog, a mirror, and shoes on the floor.

Fame and Lasting Impact

The earliest important writing about van Eyck is from 1454. An Italian writer named Bartolomeo Facio called Jan van Eyck "the leading painter" of his time. Facio placed him among the best artists of the early 1400s, alongside Rogier van der Weyden and others. It's interesting that Facio was just as excited about Dutch painters as he was about Italian ones. This old text tells us about some of Jan van Eyck's works that are now lost, like a bathing scene owned by a famous Italian.

Jan van Eyckplein (Jan van Eyck Square) in Bruges is named after him.

Images for kids

-

Detail with mirror and signature; Arnolfini Portrait, 1434

-

Virgin and Child with Canon van der Paele, around 1434–1436.

See also

In Spanish: Jan van Eyck para niños

In Spanish: Jan van Eyck para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |