Arnolfini Portrait facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Arnolfini Portrait |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Artist | Jan van Eyck |

| Year | 1434 |

| Type | Oil on oak panel of 3 vertical boards |

| Dimensions | 82.2 cm × 60 cm (32.4 in × 23.6 in); panel 84.5 cm × 62.5 cm (33.3 in × 24.6 in) |

| Location | National Gallery, London |

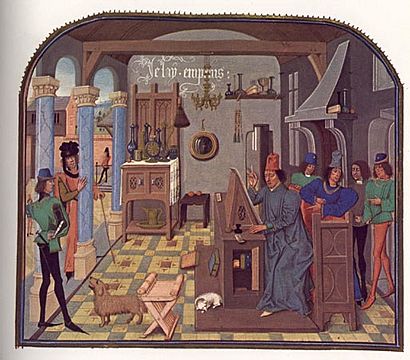

The Arnolfini Portrait is a very famous oil painting from 1434. It was created by the Dutch artist Jan van Eyck. The painting shows an Italian merchant named Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini and his wife. They are likely in their home in Bruges, a city in Flanders.

This artwork is considered one of the most original and complex paintings in Western art. It's admired for its beauty, detailed hidden meanings, and clever use of a mirror. The mirror makes the painting seem to go beyond its edges. Art experts like Ernst Gombrich said it was as new and exciting as works by Italian artists like Donatello. He felt it was like a magical snapshot of the real world. For the first time, an artist became a perfect eyewitness. Some historians, like Erwin Panofsky, even believe the painting is a unique record of a marriage contract.

Van Eyck signed and dated the painting in 1434. Along with his Ghent Altarpiece, it's one of the oldest famous panel paintings made with oils. Before this, artists mostly used tempera paint. The National Gallery in London bought the painting in 1842.

Van Eyck used a special painting method. He applied many thin, see-through layers of paint called glazes. This made the colors very bright and deep. The glowing colors also made the painting look very realistic. They showed how rich and fancy Arnolfini's world was. Oil paint dries slower than tempera. Van Eyck used this to mix colors directly on the canvas. This technique, called wet-in-wet, helped him create smooth changes in light and shadow. This made the figures look more three-dimensional. Oil paint also let van Eyck capture textures and surfaces very precisely. He showed how light from the window reflected off different objects. Some people think he used a magnifying glass to paint tiny details. For example, he painted individual highlights on each amber bead next to the mirror.

The painting's realism was amazing for its time. This was partly because of the incredible detail. But it was also because of how van Eyck used light to show the space inside the room. It gives a very convincing picture of a room and the people in it. There's been a lot of discussion about the meaning of the scene and its details. However, art expert Craig Harbison noted that it's the only 15th-century Northern painting that shows people doing something in a normal room. He even called it the first genre painting, which means a painting of everyday life.

Discovering the Details

This painting shows amazing skill in its form, brushwork, and colors. These elements create intense details, typical of the Dutch style.

The painting is in very good condition overall. There are only small areas where paint is missing or damaged. These have mostly been fixed. Special infrared scans of the painting show many small changes. These are called pentimenti. They show where the artist changed his mind while drawing. These changes are seen in the faces, the mirror, and other parts of the painting. The couple is shown in an upstairs room. It has a chest and a bed. It looks like early summer because of the fruit on the cherry tree outside the window.

This room was probably a reception room. In France and Burgundy at that time, beds in these rooms were used for sitting. They were only for sleeping if, for example, a new mother received visitors. The window has six wooden shutters inside. Only the top part has glass. It has clear round pieces set in blue, red, and green stained glass.

The two people in the painting are dressed very richly. Even though it's summer, their outer clothes are lined with fur. His long coat, called a tabard, and her dress are both trimmed with fur. His fur might be expensive sable. Hers could be ermine or miniver. He wears a black hat made of plaited straw. This was a common summer hat back then. His tabard was once more purple, but the colors have faded. It was likely made of silk velvet, which was very costly. Underneath, he wears a patterned silk damask jacket. Her dress has fancy decorative cuts on the sleeves. It also has a long train. Her blue underdress is also trimmed with white fur.

The only jewelry you can see is the woman's simple gold necklace and the rings they both wear. But both outfits would have been incredibly expensive. People at the time would have known this. Their clothes might show some restraint, especially the man's. This would fit their status as merchants. Portraits of nobles usually showed gold chains and more decorated cloth. However, the man's simple colors were also favored by Duke Phillip of Burgundy.

The room itself shows other signs of wealth. The brass chandelier is large and fancy for that time. It would have been very expensive. It probably had a system of pulleys and chains above it. This would let them lower it to manage the candles. This system might have been left out of the painting because of lack of space. The round, convex mirror at the back is in a wooden frame. Behind the glass, there are painted scenes from The Passion of Christ. This mirror is shown larger than such mirrors could actually be made back then. This is another small way van Eyck changed reality.

There is no sign of a fireplace in the room or in the mirror. Even the oranges placed casually on the left show wealth. Oranges were very expensive in Burgundy. They might have been one of the items Arnolfini traded. More signs of luxury include the fancy bed-hangings. Also, there are carvings on the chair and bench against the back wall. These are partly hidden by the bed. There is also a small Oriental carpet on the floor by the bed. Many rich people back then put such expensive carpets on tables, as they still do in the Netherlands. Giovanni Arnolfini and Philip the Good were friends. Philip sent his court painter, Jan van Eyck, to paint the Arnolfini couple. Their friendship might have started with an order for a tapestry that included images of Notre Dame Cathedral.

The mirror shows two figures just inside the door. The couple is facing them. The second figure, wearing red, is probably the artist himself. However, unlike Velázquez in Las Meninas, he doesn't seem to be painting. Experts think this is van Eyck because figures wearing red head-dresses appear in other works by him. Examples include the Portrait of a Man (Self Portrait?) and a figure in the background of the Madonna with Chancellor Rolin. The dog in the painting is an early type of the breed now known as the Brussels griffon.

The painting is signed, written on, and dated on the wall above the mirror. It says: "Johannes de eyck fuit hic 1434" ("Jan van Eyck was here 1434"). The writing looks like large letters painted on the wall. This was a common way to display sayings at that time. Other van Eyck signatures are painted to look like they are carved into the wooden frame of his paintings.

Who Are the People?

In 1857, Joseph Archer Crowe and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle first connected this painting to old lists of artworks owned by Margaret of Austria. They thought the painting showed Giovanni [di Arrigo] Arnolfini and his wife. Four years later, James Weale agreed. He identified Giovanni's wife as Jeanne (or Giovanna) Cenami. For the next 100 years, most art historians believed this was true.

However, a discovery in 1997 changed this idea. It was found that Giovanni di Arrigo and Jeanne Cenami married in 1447. This was 13 years after the painting's date and 6 years after van Eyck died.

Now, experts believe the man is either Giovanni di Arrigo or his cousin, Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini. The woman would be a wife of one of them. This could be an unknown first wife of Giovanni di Arrigo. Or it could be a second wife of Giovanni di Nicolao. A recent idea suggests it's Giovanni di Nicolao's first wife, Costanza Trenta. She might have died in childbirth by February 1433. If this is true, the painting would be a special memorial portrait. It would show one living person and one who had passed away. Details like the snuffed candle above the woman support this idea. Also, scenes after Christ's death are on her side of the mirror's frame. The man's black clothes also fit this view. Both Giovanni di Arrigo and Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini were Italian merchants from Lucca. They lived in Bruges since at least 1419. The man in this painting is also in another portrait by van Eyck in Berlin. This makes some people think he was a friend of the artist.

Journey of the Painting

The story of the painting's owners, called its provenance, starts in 1435. That's when van Eyck dated it. The person who ordered it probably owned it first. Before 1516, the painting came into the hands of Don Diego de Guevara. He was a Spanish courtier who worked for the Habsburg royal family. He lived most of his life in the Netherlands. He might have known the Arnolfinis later in their lives.

By 1516, Don Diego had given the painting to Margaret of Austria. She was the ruler of the Netherlands for the Habsburgs. It was the first item listed in her painting collection in Mechelen. The list described it as: "a large picture called Hernoul le Fin with his wife in a room, given to Madame by Don Diego, whose coat of arms is on the cover of the said picture; done by the painter Johannes." A note said it needed a lock to close it, which Margaret ordered. In another list from 1523–24, a similar description was given. This time, the subject's name was "Arnoult Fin."

In 1530, Margaret's niece, Mary of Hungary, inherited the painting. She moved to Spain in 1556. The painting is clearly described in a list made after her death in 1558. Then, Philip II of Spain inherited it. A painting of his two young daughters, Infantas Isabella Clara Eugenia and Catalina Micaela of Spain, copies the pose of the figures from the Arnolfini Portrait. In 1599, a German visitor saw it in the Alcazar Palace in Madrid. By then, verses from Ovid were painted on its frame. It's very likely that Velázquez knew the painting. It may have influenced his famous work, Las Meninas, which shows a room in the same palace.

In 1700, the painting was listed after the death of Carlos II. It still had its shutters and the verses from Ovid. The painting survived a fire in the Alcazar that destroyed many Spanish royal artworks. By 1794, it had moved to the "Palacio Nuevo," which is the current Royal Palace of Madrid.

In 1816, the painting was in London. It was owned by Colonel James Hay, a Scottish soldier. He claimed he was badly hurt at the Battle of Waterloo the year before. He said the painting was in the room where he got better in Brussels. He loved it and convinced the owner to sell it. More likely, Hay was at the Battle of Vitoria in Spain in 1813. During that battle, British troops took many artworks from a coach belonging to King Joseph Bonaparte. What was left was returned to the Spanish.

Hay offered the painting to the Prince Regent, who later became George IV of the United Kingdom. The Prince kept it for two years at Carlton House to decide if he wanted it. But he returned it in 1818. Around 1828, Hay gave it to a friend to look after. He didn't see the painting or the friend for 13 years. Then, he arranged for it to be shown in a public exhibition in 1841. The next year, in 1842, the recently formed National Gallery in London bought it for £600. It is still there today. By then, the original shutters and frame were gone.

See also

In Spanish: Retrato de Giovanni Arnolfini y su esposa para niños

In Spanish: Retrato de Giovanni Arnolfini y su esposa para niños

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |