Harry Partch facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Harry Partch

|

|

|---|---|

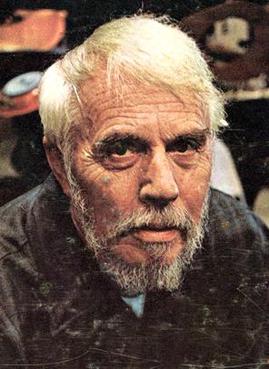

Portrait of Partch in his workshop, c. 1969

|

|

| Born | June 24, 1901 Oakland, California, U.S.

|

| Died | September 3, 1974 (aged 73) Encinitas, California, U.S.

|

| Occupation | |

Harry Partch (June 24, 1901 – September 3, 1974) was an American composer, music theorist, and a creator of very special musical instruments. He made music using scales with unusual intervals, called just intonation. He was one of the first composers in the 1900s to use microtonal scales, which have more notes than standard Western music.

To play his music, Partch built his own custom-made instruments. He gave them unique names like the Chromelodeon and the Zymo-Xyl. He also wrote a book called Genesis of a Music (1947), explaining his musical ideas. Partch's music used scales that divided the octave into 43 different tones. These tones came from the natural harmonic series.

Partch called his music "corporeal," meaning it was very physical and connected to the body. He thought it was different from "abstract music," which he felt had become common in Western music since Bach. His early pieces were small, with singing and instruments. Later, he created big theater shows where performers sang, danced, spoke, and played instruments all at once. He was inspired by ancient Greek theater and Japanese Noh and kabuki theater styles.

Partch's mother encouraged him to learn music when he was young. He started composing by age 14. He left the University of Southern California's School of Music in 1922 because he wasn't happy with the teaching. He then taught himself by reading books in libraries. There, he found Hermann von Helmholtz's book Sensations of Tone, which made him focus on music based on just intonation. In 1930, he burned all his old compositions, deciding to move away from traditional European music. Partch often moved around the U.S. He supported himself through grants, university jobs, and selling his recordings. In 1970, his supporters created the Harry Partch Foundation to manage his music and instruments.

Contents

Harry Partch's Life Story

Growing Up (1901–1919)

Harry Partch was born on June 24, 1901, in Oakland, California. His parents, Virgil and Jennie Partch, were missionaries. They lived in China for several years before Harry was born.

His family moved to Arizona for his mother's health. They settled in Benson, a small town that was still like the "Wild West." Partch remembered seeing outlaws there. He also heard the music of the native Yaqui people. His mother sang to him in Mandarin Chinese, and he heard and sang songs in Spanish. His mother encouraged him to learn music, and he learned to play the mandolin, violin, piano, reed organ, and cornet. She also taught him to read music.

In 1913, his family moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico. There, Partch studied the piano seriously. He played keyboards for silent films while in high school. By age 14, he was composing piano music. He was very interested in writing music for dramatic stories. He often mentioned an early lost piece called Death and the Desert (1916). Partch finished high school in 1919.

Early Music Experiments (1919–1947)

After his father's death, the family moved to Los Angeles in 1919. His mother died in a trolley accident in 1920. Partch enrolled in the University of Southern California's School of Music in 1920 but left in 1922, feeling unhappy with his teachers. He moved to San Francisco and studied music books in libraries, continuing to compose.

In 1923, he decided to reject the standard twelve-tone equal temperament of Western music. This happened after he found a translation of Hermann von Helmholtz's book Sensations of Tone. This book led Partch to believe that just intonation was a better basis for his music.

By 1925, Partch was putting his ideas into practice. He made special fingerings for violin and viola to play in just intonation. He wrote a string quartet using these tunings. In 1928, he wrote the first draft of a book about his theories. He worked various jobs to support himself, including teaching piano and working as a sailor. In New Orleans in 1930, he decided to completely break away from European music traditions. He burned all his earlier musical scores in a potbelly stove.

Partch had a violin maker in New Orleans build him a special viola with a cello's neck. He called this instrument the Adapted Viola. He used it to write music with a scale of twenty-nine tones in an octave. Some of his earliest surviving works are from this time, including pieces based on the Bible, Shakespeare, and Chinese poetry. In 1932, Partch performed his music in San Francisco and Los Angeles.

In 1933, a group of sponsors sent Partch to New York. He gave solo performances and gained support from other composers. Partch applied for grants but was not successful at first. However, the Carnegie Corporation of New York gave him $1500 to do research in England. He studied at the British Museum and traveled in Europe. He met the writer W. B. Yeats in Dublin. Partch wanted to set Yeats's translation of Sophocles' King Oedipus to music.

He built a keyboard instrument called the Chromatic Organ, which used a scale with forty-three tones in an octave. He also met musicologist Kathleen Schlesinger, who had rebuilt an ancient Greek kithara. Partch sketched her instrument and discussed ancient Greek music theory with her.

Partch returned to the U.S. in 1935 during the Great Depression. For nine years, he traveled a lot, often working odd jobs or getting small grants. He kept a journal during this time, which was later published as Bitter Music. He continued to compose, build instruments, and develop his theories. He built his first Kithara in 1938. In 1942, he built his Chromelodeon, another 43-tone reed organ. In 1943, he received a grant to build more instruments and finish a seven-part musical work. In 1944, his Americana compositions were performed at Carnegie Hall.

University Work (1947–1962)

With support from grants, Partch lived at the University of Wisconsin from 1944 to 1947. This was a very busy time for him. He gave lectures, trained a music group, put on performances, released his first recordings, and finished his book, Genesis of a Music. The book was published in 1949. He left the university because he was never offered a permanent job, and he needed more space for his growing collection of instruments.

In 1949, a pianist named Gunnar Johansen let Partch turn a smithy (a blacksmith's workshop) on his ranch into a studio. Partch worked there, making recordings of his music. Composer Ben Johnston helped him for six months. In 1951, Partch moved to Oakland for health reasons. He prepared for a production of King Oedipus at Mills College. The performances in March were reviewed widely.

In 1953, Partch started a studio called Gate 5 in an old shipyard in Sausalito, California. There, he composed, built instruments, and put on shows. Friends and supporters created the Harry Partch Trust Fund to raise money for recordings. These recordings were sold by mail order and became his main source of income. Partch's three Plectra and Percussion Dances were first played on radio in November 1953.

After finishing The Bewitched in 1955, Partch looked for ways to stage it. Ben Johnston introduced Danlee Mitchell to Partch at the University of Illinois. Mitchell later became very important in managing Partch's music. In 1957, The Bewitched was performed at the University of Illinois. Later in 1957, Partch created the music for Madeline Tourtelot's film Windsong. This was the first of six films they worked on together.

From 1959 to 1962, Partch worked at the University of Illinois again. He staged productions of Revelation in the Courthouse Park in 1961 and Water! Water! in 1962. These works were based on Greek mythology but had modern settings and popular music elements. Even though he had support from some parts of the university, the music department was not welcoming. This led him to leave and return to California.

Later Life in California (1962–1974)

In late 1962, Partch set up a studio in Petaluma, California, in an old chick hatchery. There, he composed And on the Seventh Day, Petals Fell in Petaluma. He left northern California in 1964 and spent his last ten years in various cities in southern California. He rarely had university jobs during this time, living on grants, commissions, and record sales. A big moment for his popularity was the 1969 Columbia LP The World of Harry Partch. This was the first modern recording of his music and his first release on a major record label.

His last theater work was Delusion of the Fury, which included music from Petaluma. It was first performed at the University of California in early 1969. In 1970, the Harry Partch Foundation was created to handle his work and expenses. His last finished piece was the soundtrack for Betty Freeman's film The Dreamer that Remains. He retired to San Diego in 1973. He died there after a heart attack on September 3, 1974. That same year, a second edition of Genesis of a Music was published with new chapters about his later work and instruments.

In 1991, Partch's journals from 1935 to 1936 were found and published. He had thought they were lost. In 1998, music expert Bob Gilmore published a book about Partch's life.

Harry Partch's Legacy

Harry Partch met Danlee Mitchell at the University of Illinois. Partch made Mitchell his heir, and Mitchell now leads the Harry Partch Foundation. Dean Drummond and his group Newband took care of Partch's instruments and performed his music. After Drummond's death in 2013, Charles Corey, one of Drummond's former students, took over caring for the instruments.

The Sousa Archives and Center for American Music in Urbana, Illinois, holds the Harry Partch Estate Archive. This collection includes Partch's personal papers, musical scores, films, tapes, and photos from his career. It also has a collection of books, music, films, and sound recordings about Harry Partch and those connected to him.

Partch's musical notation can be difficult to read. It mixes a type of tablature (showing where to place fingers) with pitch ratios. This makes it hard for musicians trained in traditional Western notation to understand, and it doesn't easily show what the music should sound like.

Paul Simon used Partch's instruments when he created songs for his 2016 album Stranger to Stranger.

Recognition

In 1974, Harry Partch was added to the Hall of Fame of the Percussive Arts Society. This organization promotes percussion education and performance. In 2004, Partch's work U.S. Highball was chosen by the Library of Congress as "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

Harry Partch's Music

Music Theory

Partch shared his musical ideas in his book Genesis of a Music (1947). In the book, he looked at music history. He argued that Western music started to decline after Bach, when the twelve-tone equal temperament system became the only tuning used. He also felt that abstract, instrument-only music became too common. Partch wanted to bring singing back to the forefront of music. He used tunings and scales that he believed were better for voices.

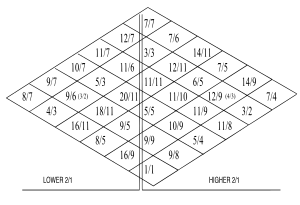

Inspired by Hermann von Helmholtz's book Sensations of Tone, Partch based his music strictly on just intonation. He tuned his instruments using the overtone series. This allowed for many more small, unequal musical intervals than the twelve-tone system of Western classical music. Partch's tuning is often called microtonality, as it uses intervals smaller than 100 cents. However, Partch saw his tuning as a return to older Western musical roots, especially to the music of ancient Greece. By using principles from Helmholtz's book, he developed a tuning system that divided the octave into 43 tones, based on simple number ratios.

Partch used the terms Otonality and Utonality to describe chords. These are chords where the notes are either the harmonics or subharmonics of a main tone. These six-tone chords work in Partch's music much like the three-tone major and minor chords do in classical music. Otonalities come from the overtone series, and Utonalities come from the undertone series.

Partch's book Genesis of a Music has influenced later composers interested in new tuning systems, such as Ben Johnston and James Tenney. Both of them worked with Partch in the 1950s.

Musical Style

Partch did not like the Western concert music tradition. He felt that the music of composers like Beethoven had weak connections to Western culture. His music often had a non-Western feel. For example, he set the poetry of Li Bai to music. He also combined two Japanese Noh dramas with one from Ethiopia in his work The Delusion of the Fury.

Partch believed that Western music in the 20th century had become too specialized. He didn't like how theater had separated music and drama. He worked to create complete, integrated theater works. In these shows, he expected every performer to sing, dance, play instruments, and speak. Partch used the words "ritual" and "corporeal" to describe his theater works. This meant that musicians and their instruments were not hidden away. Instead, they were a visible part of the performance.

Rhythm in Partch's Music

Partch's approach to rhythm varied from very free to very complex. In Seventeen Lyrics of Li Po for the Adapted Viola, Partch didn't use specific rhythmic notation. He simply told performers to follow the natural rhythms of the poem. His rhythmic structures in Castor and Pollux were much more detailed. For example, in one part, the music switched between 4 and 5 beats per measure.

Harry Partch's Instruments

Partch once called himself "a philosophic music-man seduced into carpentry." He gradually started using various unique instruments. In the 1920s, he began with traditional instruments. He even wrote a string quartet in just intonation, though it is now lost. In 1930, he had his first special instrument built: the Adapted Viola, which was a viola with a cello's neck.

Most of Partch's works used only the instruments he had created. Some pieces did use unaltered standard instruments like the clarinet or cello. For example, Revelation in the Courtyard Park (1960) used a regular small wind band, and Yankee Doodle Fantasy (1944) used an unaltered oboe and flute.

In 1991, Dean Drummond became the caretaker of Harry Partch's original instrument collection. He kept them until his death in 2013. In 1999, Drummond brought the instruments to Montclair State University in Montclair, New Jersey. In November 2014, they were moved to the University of Washington, Seattle. They are now cared for by Charles Corey, who was Drummond's student.

Harry Partch's Works

Partch's later works were large-scale, complete theater productions. In these shows, he expected each performer to sing, dance, speak, and play instruments.

Partch explained his music theory and practice in his book Genesis of a Music. It was first published in 1947, and an expanded edition came out in 1974. A collection of his essays, journals, and librettos (the words of his musical works) was published after his death in 1991 as Bitter Music.

Partch partly supported himself by selling recordings, which he started making in the late 1930s. He released his recordings under the Gate 5 Records label starting in 1953. On some recordings, like the soundtrack to Windsong, he used multitrack recording. This allowed him to play all the instruments himself. He never used synthesized or computer-generated sounds, even though he had access to such technology. Partch composed music for six films by Madeline Tourtelot, starting with Windsong in 1957. He has also been the subject of several documentary films.

|

See also

In Spanish: Harry Partch para niños

In Spanish: Harry Partch para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |