Kabuki facts for kids

Kabuki (歌舞伎, かぶき) is a special kind of Japanese theater. It mixes exciting performances with traditional Japanese dance. Kabuki is famous for its unique style, amazing costumes, and the detailed make-up called kumadori that some actors wear.

Kabuki started a long time ago, in the early Edo period (around the 1600s). A woman named Izumo no Okuni created a dance group that performed in Kyoto. At first, women performed in Kabuki. But later, in 1629, women were not allowed to perform anymore. After that, only men performed Kabuki. The art form grew popular in the late 1600s and was at its best in the mid-1700s.

In 2005, UNESCO recognized Kabuki as a very important cultural heritage. It was added to the UNESCO list of important cultural traditions in 2008.

Contents

What Does "Kabuki" Mean?

The word Kabuki is made of three Japanese characters:

- 歌 (ka) means 'sing'.

- 舞 (bu) means 'dance'.

- 伎 (ki) means 'skill'.

So, Kabuki is sometimes called 'the art of singing and dancing'. The 'skill' character often refers to the performers themselves.

The word Kabuki actually comes from the verb kabuku. This means 'to lean' or 'to be out of the ordinary'. So, Kabuki can also mean 'avant-garde' or 'unusual' theater. People called kabukimono were known for dressing in strange ways. They were often samurai gangs who wore very unique clothes.

The Story of Kabuki

Early Kabuki: When Women Performed (1603–1629)

Kabuki began in 1603. Izumo no Okuni, who might have been a shrine maiden, started performing a new dance drama. She performed with a group of female dancers on a simple stage in Kyoto. This was at the very start of the Edo period, when the Tokugawa shogunate ruled Japan.

In the beginning, female performers played both men and women. They acted in short, funny plays about everyday life. This style quickly became popular. Okuni was even asked to perform for the Emperor's court. Soon, other groups formed, and Kabuki became a popular dance and drama performed by women.

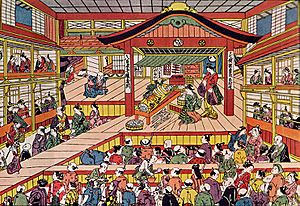

Many different kinds of people came to watch Kabuki. This was unusual in the city of Edo. Kabuki theaters became places to show off new fashions. Rich merchants, who had a lot of money but were not high in social class, often used performances to display their trendy clothes.

Kabuki also brought new entertainment. It featured new music played on the shamisen (a Japanese string instrument). The costumes were often very dramatic. Famous actors performed stories that sometimes reflected current events. Shows usually lasted all day, from morning until sunset. Teahouses nearby offered food and drinks, and people could socialize there. Shops around the theaters sold Kabuki souvenirs.

However, the government (shogunate) did not like Kabuki performances. They worried about different social classes mixing. They also disliked how merchants showed off their wealth and fashion, which seemed to challenge the samurai class. To control Kabuki's popularity, the government banned onna-kabuki (women's Kabuki) in 1629. After this, young boys started performing in wakashū-kabuki, but this was also soon banned. By the mid-1600s, Kabuki switched to adult male actors, called yarō-kabuki. These male actors continued to play both female and male characters. Kabuki stayed popular and was a big part of city life in the Edo period.

Kabuki was performed all over Japan. But the Nakamura-za, Ichimura-za, and Kawarazaki-za theaters were the most famous. Many successful Kabuki shows were held there, and some still are.

Kabuki Changes to All-Male Actors (1629–1673)

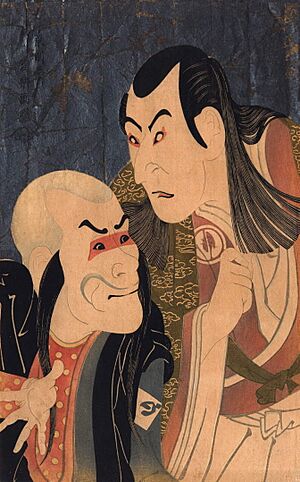

Between 1628 and 1673, Kabuki became an all-male art form. This style was called yarō-kabuki (meaning "young man Kabuki"). It happened after women and young boys were banned from performing. Male actors who played women's roles were called onnagata or oyama. Young men were often chosen for female roles because they looked less masculine and had higher voices. Roles for adolescent men, called wakashu, were also played by young men, often chosen for their good looks.

Kabuki performances also started to focus more on drama, not just dance. Audiences sometimes got very rowdy, and fights even broke out. This sometimes happened because people argued over popular actors. Because of this, the government briefly banned onnagata and then wakashū roles. But both bans were lifted by 1652.

Kabuki's Golden Age: Genroku Period (1673–1841)

During the Genroku period, Kabuki really grew. The way Kabuki plays were structured became more formal, like they are today. Many other traditions, like common character types, also became part of Kabuki. Kabuki theater and ningyō jōruri (a type of puppet theater later called bunraku) became very close. They influenced each other's development.

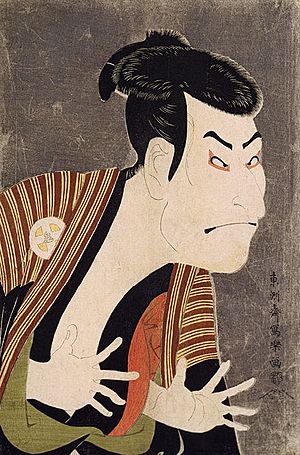

This period also saw the creation of the mie pose. This is a special pose an actor holds to show their character's feelings. The actor Ichikawa Danjūrō I is given credit for starting this. Also, the mask-like kumadori make-up, worn by actors in some plays, was developed then.

In the mid-1700s, Kabuki became less popular for a while. Bunraku (puppet theater) took its place as the main stage entertainment for common people. This happened partly because many talented bunraku writers appeared. Kabuki didn't change much until the end of the century, when it started to become popular again.

Kabuki Moves to Saruwaka-chō (1842–1868)

In the 1840s, many fires happened in Edo because of dry weather. Kabuki theaters, which were usually made of wood, often burned down. This forced many theaters to move. When the Nakamura-za theater was completely destroyed in 1841, the government (shōgun) would not let it be rebuilt. They said it was against fire safety rules.

The government didn't like how merchants and actors mixed in Kabuki theaters. So, they used the fire crisis to their advantage. In 1842, they forced the Nakamura-za, Ichimura-za, and Kawarazaki-za theaters to move outside the city limits to Asakusa, a suburb of Edo. This was part of bigger changes called the Tenpō Reforms, which aimed to stop people from enjoying too many pleasures. Actors and stagehands also had to move. Even though everyone involved in Kabuki moved, the long distance made fewer people come to shows. These problems, along with strict rules, pushed much of Kabuki "underground" in Edo. Performances moved to secret locations to avoid the authorities.

The new theater area was called Saruwaka-chō. The last 30 years of the Tokugawa shogunate's rule are often called the "Saruwaka-machi period." This time is known for having some of the most dramatic Kabuki in Japanese history.

Saruwaka-machi became the new theater district for the Nakamura-za, Ichimura-za, and Kawarazaki-za theaters. The district was on the main street of Asakusa. The street was named after Saruwaka Kanzaburo, who started Edo Kabuki at the Nakamura-za in 1624.

European artists like Claude Monet started to notice Japanese theater and art. Many were inspired by Japanese woodblock prints. This interest from the West made Japanese artists draw more scenes from daily life, including theaters and streets. One artist, Utagawa Hiroshige, made a series of prints about Saruwaka during this time.

Even though Kabuki moved, the new location made it harder to find ideas for costumes, make-up, and stories. Ichikawa Kodanji IV was a very active and successful actor during this period. He was not considered handsome, so he mostly performed buyō (dancing) in plays written by Kawatake Mokuami. Kawatake Mokuami also wrote during the Meiji Restoration period that followed. He often wrote plays about the lives of common people in Edo. He introduced a special dialogue style (seven-and-five syllable meter) and music like kiyomoto. His Kabuki performances became very popular after the Saruwaka-machi period ended and theater returned to Edo. Many of his plays are still performed today.

In 1868, the Tokugawa government ended, and the Emperor was restored to power. Emperor Meiji moved from Kyoto to the new capital of Edo, which was renamed Tokyo. This started the Meiji period. Kabuki returned to the entertainment areas of Edo. During the Meiji period, Kabuki became more modern. New styles of plays and performances appeared. Playwrights tried new types of stories and added twists to old tales.

Kabuki After the Meiji Period

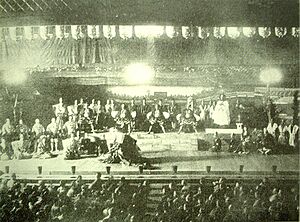

After 1868, big cultural changes happened in Japan. The Tokugawa government fell, the samurai class ended, and Japan opened up to Western countries. These changes helped Kabuki become popular again. Both actors and writers worked to make Kabuki's reputation better. They wanted to adapt traditional styles for modern tastes and appeal to upper classes. This worked, and the Emperor even sponsored a Kabuki performance in 1887.

After World War II, the American forces briefly banned Kabuki. This was because Kabuki had supported Japan's war efforts since 1931. The ban was part of bigger rules on media and art that the American military put in place after the war. But by 1947, the ban on Kabuki was lifted, though some censorship rules remained.

Kabuki Today

The time after World War II was hard for Kabuki. Besides the damage from the war, some people wanted to reject old Japanese styles and art forms, including Kabuki. But director Tetsuji Takechi created popular and new versions of classic Kabuki plays. These helped bring new interest to Kabuki in the Kansai region. Nakamura Ganjiro III (born 1931) was a leading young star in Takechi Kabuki. This time in Osaka is even called the "Age of Senjaku" in his honor.

Today, Kabuki is the most popular traditional Japanese drama. Its star actors often appear on TV or in movies. For example, the famous onnagata actor Bandō Tamasaburō V has acted in non-Kabuki plays and movies, often playing women.

Kabuki also appears in Japanese popular culture, like anime. Besides the main theaters in Tokyo and Kyoto, there are many smaller theaters in Osaka and other parts of the country. The Ōshika Kabuki group, for example, is based in Ōshika, Nagano.

Some local Kabuki groups today use female actors for onnagata roles. The Ichikawa Shōjo Kabuki Gekidan, an all-female group, started in 1953 and was very popular. However, most Kabuki groups are still all-male.

To make Kabuki more appealing, earphone guides were introduced in 1975, with an English version in 1982. This helped more people understand and enjoy the art form. Because of this, in 1991, the Kabuki-za, a famous theater in Tokyo, started performing all year. In 2005, they even began selling Kabuki movies. Kabuki groups often tour in Asia, Europe, and America. There have also been Kabuki versions of Western plays, like those by William Shakespeare. Western writers have also used Kabuki ideas in their works. For example, Gerald Vizenor wrote Hiroshima Bugi (2004). Writer Yukio Mishima helped make Kabuki popular in modern settings and brought back other traditional arts, like Noh, adapting them for today's world. There are even Kabuki groups outside Japan. For instance, in Australia, the Za Kabuki group at the Australian National University has performed a Kabuki play every year since 1976. This is the longest regular Kabuki performance outside Japan.

In 2002, a statue was put up to honor Izumo no Okuni, the founder of Kabuki. It marked 400 years of Kabuki's existence. The statue stands across from the Minami-za, the last Kabuki theater in Kyoto, by the Kamo River.

Kabuki was added to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists in 2005.

Super Kabuki

Ichikawa En-ō wanted to make Kabuki more popular while still keeping its traditions. So, he created a new type of Kabuki called "Super Kabuki." The first Super Kabuki show was Yamato Takeru in 1986. Since then, old plays have been remade, and new modern shows have been created. Some even include anime characters, like Naruto or One Piece, starting in 2014.

Super Kabuki has caused some debate in Japan. Some people say it has lost its 400-year history. Others believe these changes are needed to keep it interesting for today's audiences. But by using more advanced technology in stage sets, costumes, and lighting, Super Kabuki has attracted younger people.

In 2022, Square Enix announced a Super Kabuki version of Final Fantasy X. It will be part of the Final Fantasy series' 35th anniversary. The show, called Kinoshita Group presents New Kabuki Final Fantasy X, is set to be performed in Tokyo from March to April 2023.

How Kabuki is Performed

Stage Design and Tricks

The Kabuki stage has a special walkway called a hanamichi (flower path). This walkway goes into the audience. Actors use it to make dramatic entrances and exits. Izumo no Okuni also used a hanamichi stage. This path is not just for walking; important scenes are also performed on it.

Kabuki stages have become very advanced over time. Revolving stages and trap doors were added in the 1700s. These innovations help show sudden changes or revelations, which is a common theme in Kabuki. Many stage tricks, like actors appearing and disappearing quickly, use these new features. The word keren is used for these visual tricks. The hanamichi, revolving stages, seri (trap doors), and chunori (flying) all add to the excitement of Kabuki. The hanamichi creates depth, and seri and chunori add a vertical dimension.

The mawari-butai (revolving stage) was developed between 1716 and 1735. At first, people on stage pushed a round platform with wheels. Later, a circular platform was built into the stage with wheels underneath to make it move easily. When the stage revolves in the dark, it's called kuraten. More often, the lights stay on for akaten (lighted revolve), sometimes with scenes happening at the same time for more drama. This type of stage was first built in Japan in the early 1700s.

Seri refers to the stage "traps" used in Kabuki since the mid-1700s. These traps raise and lower actors or parts of the set. Seridashi or seriage means traps moving up. Serisage or serioroshi means traps going down. This trick is often used to lift an entire scene at once.

Chūnori (riding in mid-air) is a trick that appeared in the mid-1800s. An actor's costume is attached to wires, and they "fly" over the stage or parts of the audience. This is like the flying trick in the musical Peter Pan. It's still one of the most popular keren (visual tricks) in Kabuki today. Major Kabuki theaters have chūnori setups.

Scenery changes sometimes happen during a scene, while actors are still on stage and the curtain is open. This can be done using a Hiki Dōgu, a "small wagon stage." This trick started in the early 1700s, where scenery or actors move on or off stage on a wheeled platform. Also common are stagehands who rush onto the stage to add or remove props and backdrops. These kuroko are always dressed completely in black and are traditionally considered invisible. Stagehands also help with quick costume changes called hayagawari.

When a character's true nature is suddenly revealed, tricks like hikinuki and bukkaeri are often used. This involves wearing one costume over another. A stagehand quickly pulls off the outer costume in front of the audience.

The curtain that covers the stage before the show and during breaks has traditional colors: black, red, and green stripes, or sometimes white instead of green. The curtain is one piece and is pulled to one side by a staff member.

A second, outer curtain called doncho was added later, during the Meiji era, after Western influences. These curtains are more decorative and woven. They often show the season in which the performance is taking place. Famous Japanese artists often design them.

Costumes and Make-up

In the 1600s, laws in Japan stopped people from copying the looks of samurai or nobles. They also banned using very fancy fabrics. Because of this, Kabuki costumes were new and exciting designs for the public. They even started fashion trends that still exist today.

We don't have the very first Kabuki costumes. But today's otoko (male) and onnagata (female role) costumes are made based on old drawings called ukiyo-e. They are also made with help from families who have been in the Kabuki business for many generations. The kimonos actors wear are usually very colorful and have many layers. Both otoko and onnagata wear hakama (pleated trousers) in some plays. They also use padding under their costumes to create the right body shape for the outfit.

Kabuki make-up is a very recognizable part of the style. Even people who don't know much about Kabuki can spot it. Rice powder is used to create the white oshiroi base for the stage make-up. Kumadori make-up makes facial lines stronger or more dramatic. It creates mask-like looks for animal or supernatural characters. The color of the kumadori shows the character's personality:

- Red lines mean passion, heroism, or good traits.

- Blue or black lines mean evil, jealousy, or bad traits.

- Green lines mean supernatural beings.

- Purple lines mean nobility.

Another special part of Kabuki costumes is the katsura, or wig. Each actor has a different wig made for every role. They are built on a thin base of hand-beaten copper, custom-made to fit the actor perfectly. Each wig is usually styled in a traditional Japanese way. The hair used in the wigs is usually real human hair sewn onto a fabric base. Some wig styles need yak hair or horse hair.

Types of Kabuki Plays

There are three main types of Kabuki plays:

- Jidaimono: Historical stories, set before the Sengoku period.

- Sewamono: "Domestic" stories, set after the Sengoku period.

- Shosagoto: Dance pieces.

Jidaimono, or history plays, are set during important times in Japanese history. Strict rules during the Edo period stopped plays from showing current events or criticizing the government. But these rules were not always enforced the same way. Many shows were set during the Genpei War (1180s) or the Nanboku-chō period (1330s). To get around the censors, many plays used these historical settings to talk about current events in a hidden way. Kanadehon Chūshingura, one of the most famous Kabuki plays, is a great example. It seems to be set in the 1330s, but it actually tells the story of the Forty-seven rōnin from the 1700s.

Unlike jidaimono, which usually focused on the samurai class, sewamono focused on common people, like townspeople and farmers. These are often called "domestic plays" in English. Sewamono usually dealt with family drama and romance.

Shosagoto plays focus on dance. They can be performed with or without talking. Dance is used to show feelings, character, and the story. Quick costume changes are sometimes used in these plays. Famous examples include Musume Dōjōji and Renjishi. Musicians called nagauta may sit in rows on raised platforms behind the dancers.

An important part of Kabuki is the mie. This is when the actor holds a striking pose to show their character. At this moment, an expert audience member might shout the actor's family name (yagō). This shows how much they appreciate the actor's performance. Shouting the name of the actor's father is an even bigger compliment.

The main actor must show many different feelings. For example, in Chūshingura, the character Yuranosuke seems like a drunkard but is actually faking his weakness. This is called hara-gei, or "belly acting." It means the actor performs from deep inside to change characters. It's a difficult skill to learn, but when done well, the audience feels the actor's emotions.

Emotions are also shown through the colors of the costumes. Bright and strong colors can show foolish or joyful feelings. Dark or muted colors show seriousness and focus.

How Plays are Structured

Kabuki, like other traditional Japanese dramas, used to be performed in full-day shows. One play could have many acts that lasted all day. However, these plays, especially sewamono, were often mixed with acts from other plays to create a full-day program. This is because individual acts in Kabuki often worked as stand-alone performances. Sewamono plays, on the other hand, were usually not mixed with other plays and truly took the whole day to perform.

The structure of a full-day performance came from bunraku and Noh theater. The most important idea was jo-ha-kyū. This is a pacing rule that says a play's action should start slow, speed up, and end quickly. This idea, explained by the Noh playwright Zeami, controls not only the actors' movements but also the structure of the play, scenes, and even the whole day's program.

Almost every full-length play has five acts.

- The first act is jo. It's a slow and lucky opening that introduces the characters and the story.

- The next three acts are ha. Events speed up, usually ending with a big dramatic or sad moment in the third act. There might also be a battle in the second or fourth acts.

- The final act is kyū. It's almost always short, giving a quick and satisfying ending.

Many plays were written just for Kabuki. But many others came from jōruri plays, Noh plays, old stories, or other traditions like the oral story of the Tale of the Heike. Jōruri plays usually have serious, emotional, and organized plots. Plays written only for Kabuki often have looser, funnier plots.

One key difference between jōruri and Kabuki is what they focus on. Jōruri focuses on the story and the person who tells it. Kabuki focuses more on the actors themselves. A jōruri play might not have detailed sets or puppets to highlight the chanter. But Kabuki might change the drama or even the plot to show off an actor's skills. It was common in Kabuki to add or remove scenes from a day's schedule to suit a particular actor. This could be scenes they were famous for, or scenes that featured them, even if it broke the story's flow. Some plays were also rarely performed because they needed an actor who could play many musical instruments live on stage, a skill few actors had.

Kabuki traditions in Edo (Tokyo) and the Kyoto-Osaka region (Kamigata) were different. During the Edo period, Edo Kabuki was known for being very fancy. This included the actors' looks, costumes, stage tricks, and bold mie poses. In contrast, Kamigata Kabuki focused on natural and realistic acting styles. The two styles only started to mix a lot towards the end of the Edo period. Before this, actors from different regions often struggled to adjust their acting styles when performing elsewhere. This led to unsuccessful tours outside their usual region.

Famous Kabuki Plays

Many famous Kabuki plays today were written in the mid-Edo period. Many of them were first written for bunraku theater.

- Kanadehon Chūshingura (Treasury of Loyal Retainers) is the famous story of the Forty-seven rōnin. These loyal warriors, led by Oishi Kuranosuke, get revenge on their enemy after their master dies. This is one of the most popular traditional stories in Japan. It is based on a real event from the 1700s.

- Yoshitsune Senbon Zakura (Yoshitsune and the Thousand Cherry Trees) follows Minamoto no Yoshitsune as he runs from his brother Yoritomo. Three generals from the Taira clan, who were thought to have died in the Genpei War, play a big part. Their deaths help end the war and bring peace. A kitsune (fox spirit) named Genkurō is also important in the story.

- Sugawara Denju Tenarai Kagami (Sugawara and the Secrets of Calligraphy) is based on the life of the famous scholar Sugawara no Michizane (845–903). He is sent away from Kyoto. After he dies, he causes many disasters in the capital. He is then made a god, Tenjin, the kami (divine spirit) of scholarship. People worship him to calm his angry spirit.

Kabuki Actors

Every Kabuki actor has a stage name, which is different from their birth name. These stage names are usually passed down from an actor's father, grandfather, or teacher. They are very important and honorable. Many names are linked to certain roles or acting styles. The new actor who takes the name must live up to these expectations. It's almost like the actor is not just taking a name, but also taking on the spirit, style, or skill of every actor who had that name before. Many actors will have at least three different names during their career.

Shūmei (name succession) are big naming ceremonies held in Kabuki theaters in front of the audience. Often, several actors will take on new stage names in one ceremony. Their participation in a shūmei means they are starting a new part of their acting career.

Kabuki actors usually belong to a school of acting or are connected to a specific theater.

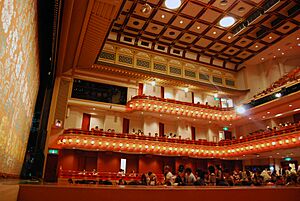

Major Kabuki Theaters

- Akita

- Kosaka

- Tokyo

- Kabuki-za

- Meiji-za

- Shinbashi Enbujō

- National Theater

- Kyoto

- Minami-za

- Osaka

- Shin-Kabuki-za (新歌舞伎座 (大阪))

- Osaka Shōchiku-za (大阪松竹座)

- Nagoya

- Misono-za

- Suehiro-za

- Fukuoka

- Hakata-za

- Kagawa

- Kotohira Kanamaru-za

How Kabuki Influences Other Arts

Since it began, Kabuki has been a very important part of Japanese culture. Its stories and actors have been shown in many other art forms. These include woodblock prints, books, magazines, oral storytelling, and later, photography. Kabuki has also been influenced by the books and stories popular in Japan. For example, the very popular book Nansō Satomi Hakkenden, or Eight Dogs, was performed in many episodes on the Kabuki stage.

One important way common people could enjoy Kabuki without going to the theater was through local shows called Noson kabuki (village kabuki). These "amateur kabuki" performances happened all over Japan, but were most common in Gifu and Aichi prefectures. In Gifu Prefecture, noson kabuki was a big part of the yearly autumn festival. Children would even act out Kabuki performances at Murakuni shrine for over 300 years.

Closer to the main Kabuki centers in Edo (Tokyo), commoners had other ways to enjoy performances. Bunraku (puppet theater) was shorter and cheaper than Kabuki. Bunraku shows often used plots from Kabuki, and both styles shared similar themes. Kabuki shinpō (Kabuki news) was another popular way for both commoners and rich people to enjoy Kabuki. This magazine allowed those who couldn't attend shows to still experience the excitement of Kabuki culture.

See Also

In Spanish: Kabuki para niños

In Spanish: Kabuki para niños

- Theatre of Japan

- Kanteiryū, a special writing style used to advertise Kabuki shows.

- Kyōgen, a funny Japanese theater style that influenced Kabuki.

- Oshiguma, an imprint of Kabuki actors' make-up, used as art or souvenirs.

- Noh, another traditional Japanese theater style.

- Bunraku, a Japanese puppet theater from which many Kabuki plays were adapted.

- Famous Kabuki actor families, like:

- Ichikawa Danjūrō

- Ichikawa Ebizō

- Matsumoto Kōshirō

- Nakamura Kanzaburō

- Kataoka Nizaemon

- Kabuki shinpō, a Japanese magazine about Kabuki that was published from 1879–1897.

- Sgt. Kabukiman NYPD, a superhero movie from 1991.

- Kabukibu!, a light novel, manga, and anime series about a boy who loves Kabuki.

- Kathakali

- Jingju

- Yakshagana

- Balinese dance

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |