Peking opera facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Peking opera |

|

|---|---|

Peking opera in Shanghai, 2014

|

|

| Etymology | From Peking, the postal romanization of Beijing |

| Other names | Beijing opera, Pekingese opera, Jing opera, Jingju, Jingxi, Guoju |

| Stylistic origins | Hui opera, Kunqu, Qinqiang, Han opera |

| Peking opera | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

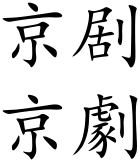

"Peking Opera" in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 京劇 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 京剧 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Capital drama | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 京戲 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 京戏 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Capital play | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Second alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 國劇 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 国剧 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | National drama | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Former name (mainly used 19th century) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 皮黃 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 皮黄 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Former name (mainly used 1927–1949) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 平劇 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 平剧 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Beiping's drama | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

Peking opera, also known as Beijing opera (Chinese: 京劇; pinyin: Jīngjù), is a famous type of Chinese opera. It mixes music, singing, acting without words (mime), dance, and amazing acrobatics. This art form started in Beijing in the mid-Qing dynasty (1644–1912). It became fully developed and well-known by the mid-1800s.

Peking opera was very popular with the Qing court, which was like the royal family of China. Today, it is seen as one of China's most important cultural treasures. Big performance groups are found in Beijing, Tianjin, and Shanghai. This art form is also kept alive in Taiwan, where it is called Guójù (Chinese: 國劇; literally "National opera"). Peking opera has even spread to other countries like the United States and Japan.

Peking opera has four main types of characters:

- Sheng (gentlemen)

- Dan (women)

- Jing (strong, often rough men)

- Chou (clowns)

Performers wear detailed and colorful costumes. They are the main focus on the stage, which is usually quite empty. They use skills like speaking, singing, dancing, and fighting. Their movements are symbolic, meaning they represent something, rather than being totally realistic. The beauty of their movements is very important. Performers also follow special rules to help the audience understand the story. Every movement has layers of meaning and must match the music.

The music in Peking opera has two main styles: xīpí (西皮) and èrhuáng (二黄). The songs include arias (solo songs), fixed tunes, and drum patterns. There are over 1,400 Peking opera plays. Most are based on Chinese history, folklore, and sometimes modern life.

During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), traditional Peking opera was criticized. It was called "old-fashioned" and "fancy." Instead, mostly revolutionary operas were performed until the revolution ended. After this period, many of the old traditions came back. Recently, Peking opera has tried new things to attract more people. These changes include making performances better, adding new elements, shortening plays, and creating new stories.

Contents

What is Peking Opera?

The Meaning Behind the Name

"Peking opera" is the English name for this art form. It was added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 1953. "Beijing opera" is a newer name that means the same thing.

In China, this art form has had many names over time. Its first Chinese name was Pihuang. This name came from combining the xipi and erhuang music styles. As it became more popular, it was called Jingju or Jingxi. These names showed that it started in the capital city (Chinese: 京; pinyin: Jīng).

From 1927 to 1949, Beijing was called Beiping. During this time, Peking opera was known as Pingxi or Pingju. After 1949, when the People's Republic of China was formed, the capital's name went back to Beijing. So, the official name for this theater in Mainland China became Jingju. In Taiwan, it is called Guoju, which means 'national drama'. This name shows the different ideas about the Chinese government.

The Story of Peking Opera

How Peking Opera Began

Peking opera started in 1790. This was when the 'Four Great Anhui Troupes' brought Hui opera (now called Huiju) to Beijing. They came for the 80th birthday of the Qianlong Emperor. At first, it was only performed for the emperor and his court. Later, it became available to everyone.

In 1828, famous groups from Hubei came to Beijing. They performed with the Anhui groups. This mix of styles slowly created the music of Peking opera. By 1845, Peking opera was fully formed. Even though it's called Peking opera (Beijing style), it actually started in southern Anhui and eastern Hubei.

Peking opera's two main music styles, Xipi and Erhuang, came from Han Opera around 1750. Han opera is often called the "Mother of Peking opera" because their tunes are so similar. Xipi means 'Skin Puppet Show'. This refers to puppet shows from Shaanxi province that always included singing.

Peking opera also took music from other operas and local art forms. Some experts think the Xipi music came from the old Qinqiang opera. Many of its stage rules, performance styles, and artistic ideas came from Kunqu, which was popular before it.

So, Peking opera is not just one thing. It's a blend of many older art forms. But it also added new things. For example, the singing parts for main characters were made easier. The Chou (clown) rarely sings in Peking opera, which is different from the clown role in Kunqu. The music was also simplified and uses different instruments. Most notably, real acrobatics were added to Peking opera.

The art form became more and more popular in the 1800s. The Anhui groups were at their best in the mid-1800s. They were even invited to perform for the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. Starting in 1884, the Empress Dowager Cixi regularly supported Peking opera. This made it even more important than older forms like Kunqu. Peking opera's popularity was also due to its simple style, with only a few voices and singing patterns. This made it easier for people to sing the songs themselves.

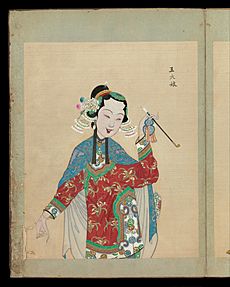

In the late 1800s, albums were used to show off stage culture. These included pictures of performers' makeup and costumes.

Women on Stage

At first, only men performed Peking opera. Women were not allowed to perform, and there were many rules for female audience members. So, the art form mainly pleased male audiences. Chinese emperors had banned female performers many times, starting in 1671. The last ban was in 1772 by the Qianlong Emperor.

Women started appearing on stage unofficially in the 1870s. Female performers began to play male roles and demanded to be treated equally. They got a chance to show their skills when Li Maoer, a former Peking opera performer, started the first female Peking opera group in Shanghai. By 1894, the first public theater showing female groups opened in Shanghai. This encouraged more female groups to form, and they became more popular.

Because of this, a theater artist named Yu Zhenting asked for the ban to be lifted. This happened after the Republic of China was founded in 1911. The ban was lifted in 1912. However, male actors playing female roles (called Dan) remained popular for some time after this.

Peking Opera in Modern Times

In the second half of the 1900s, fewer people watched Peking opera. This happened because performances sometimes weren't as good, and the old opera style didn't seem to fit modern life. Also, the old language used in Peking opera meant plays needed electronic subtitles. Young people, influenced by Western culture, also found the slow pace of Peking opera difficult.

To fix this, Peking opera started to change in the 1980s. These changes included:

- Creating new ways to teach acting to make performances better.

- Adding modern elements to attract new audiences.

- Performing new plays that were not part of the old traditions.

However, these changes faced problems like not enough money and a political situation that made it hard to perform new plays.

Besides official changes, Peking opera groups also made unofficial changes in the 1980s. Some changes in traditional plays were just "techniques for show." This included female Dan actors singing very high notes for a long time. Also, longer dance parts and drum sequences were added to old plays. Many Peking opera performers didn't like these changes. They saw them as tricks to get quick audience attention. Plays with repeated parts were also shortened to keep people interested.

New plays had more freedom to try new things. They used regional, popular, and even foreign techniques. This included Western-style makeup and new face paint designs for Jing characters. The spirit of change continued in the 1990s. To survive, groups like the Shanghai Peking Opera Company started offering more free performances in public places.

There has also been a change in who creates Peking opera works. Traditionally, the performer played a big role in writing and staging plays. But now, like in the West, Peking opera has moved towards a model where directors and playwrights have more control. Performers try to be creative while also following the new ideas from these leaders.

Channel CCTV-11 in Mainland China now shows classic Chinese opera, including Peking opera.

Peking Opera Around the World

Peking opera is not just in mainland China. It is also found in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Chinese communities in other countries.

Mei Lanfang, a very famous Dan performer, helped make Peking opera popular around the world. In the 1920s, he performed in Japan. This led to a tour in the United States in February 1930. Some people thought Peking opera wouldn't succeed in the U.S. But Mei and his group were very well-received in New York City. Their shows had to move to a bigger theater, and the tour was extended from two to five weeks. Mei traveled across the U.S. and even received special degrees from universities. He then toured the Soviet Union in 1935.

The theater department at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa has been performing Jingju in English for over 25 years. The school offers Asian Theater as a major and regularly puts on Jingju shows.

Meet the Performers and Roles

Peking opera has special character types, each with unique looks and ways of performing.

Sheng (Male Roles)

The Sheng (生) is the main male role in Peking opera. There are many types of Sheng characters:

- The laosheng is a respected older man. These characters are gentle and educated. They wear simple, tasteful costumes.

- A special laosheng is the hongsheng, an older man with a red face. Only two characters are hongsheng: Guan Gong (the Chinese God of War) and Zhao Kuang-yin (the first Song Dynasty emperor).

- Young male characters are called xiaosheng. They sing in a high, sharp voice, sometimes with breaks, to show a changing voice. Their costumes can be fancy or simple, depending on their social status.

- The wusheng is a warrior character who performs combat scenes. They are very skilled in acrobatics and sing with a natural voice.

Every Peking opera group will have a laosheng actor. A xiaosheng actor might also join for younger roles. There will also be a secondary laosheng.

Dan (Female Roles)

The Dan (旦) refers to any female role in Peking opera. Originally, there were five types of Dan roles:

- Old women were played by laodan.

- Martial women were wudan.

- Young female warriors were daomadan.

- Virtuous and noble women were qingyi.

- Lively and unmarried women were huadan.

Mei Lanfang, a famous performer, created a sixth type: the huashan. This role combines the high status of the qingyi with the charm of the huadan. A group will have a young Dan for main roles and an older Dan for smaller parts. Famous Dan performers include Mei Lanfang, Cheng Yanqiu, Shang Xiaoyun, and Xun Huisheng. In the early days, all Dan roles were played by men. Wei Changsheng, a male Dan performer, even created a "false foot" technique to imitate the small, bound feet of women and their special way of walking.

Jing (Painted Face Male Roles)

The Jing (净) is a male role with a painted face. They can play main or supporting roles. These characters are strong and powerful, so a Jing must have a loud voice and be able to make big gestures. Peking opera has 16 basic face paint patterns, but over 100 specific designs exist. The patterns and colors come from old Chinese ideas about color symbolism and face reading, which were thought to show a person's personality.

- Red faces mean honesty and loyalty.

- White faces mean evil or tricky characters.

- Black faces mean characters who are fair and honest.

There are three main types of Jing roles:

- dongchui: a loyal general with a black face who is excellent at singing.

- jiazi: a complex character played by a very skilled actor.

- wujing: a warrior and acrobatic character.

Chou (Clown Roles)

The Chou (丑) is the male clown role. Chou characters usually play supporting parts. The name chou sounds like the Mandarin Chinese word for 'ugly'. This comes from the old belief that a clown's ugliness and laughter could scare away evil spirits.

Chou roles can be:

- Wen Chou: civilian roles like merchants or jailers.

- Wu Chou: minor military roles.

The Wu Chou combines funny acting with acrobatics. Chou characters are usually amusing and likable, even if they are a bit silly. Their costumes can be simple for lower-status characters or very fancy for high-status ones. Chou characters wear special face paint called xiaohualian. This is different from Jing characters' paint. The main feature of this paint is a small white patch around the nose. This can mean a mean or secretive nature, or a quick wit.

The Chou character is closely linked to the guban (drums and clapper) used in the music. The Chou actor often uses the guban when performing alone, especially for funny, light-hearted verses called Shu Ban. The clown is also connected to the small gong and cymbals. These instruments represent lower classes and a lively atmosphere.

Even though Chou characters don't sing often, their arias (songs) have a lot of improvisation. This is allowed for their role. The orchestra will even play along if the Chou actor suddenly sings an unscripted folk song. However, due to rules and government pressure, Chou improvisation has become less common. The Chou has a unique voice. They often speak in the common Beijing dialect, unlike other characters who use more formal dialects.

How Performers Train

Becoming a Peking opera performer takes a long and tough training period, starting at a young age. Before the 1900s, teachers would choose students when they were very young. The students would train for seven years under a contract from their parents. The teacher provided everything for the student during this time. The student then repaid this "debt" through their performance earnings later.

After 1911, training moved to more organized schools. Students at these schools would wake up as early as five in the morning to exercise. During the day, they learned acting and combat skills. Older students performed in theaters in the evening. If they made any mistakes during performances, the whole group could be hit with bamboo canes. Less strict schools started appearing in 1930. But all schools closed in 1931 after the Japanese invasion. New schools didn't open until 1952.

Performers first learn acrobatics, then singing and gestures. Several performance styles are taught, based on famous performers. Examples include the Mei Lanfang school and the Cheng Yanqiu school. Students used to only learn performing arts. But modern schools now also include regular school subjects. Teachers decide what each student is good at and assign them roles as main, secondary, or supporting characters. Students who aren't strong in acting often become Peking opera musicians. They might also play supporting roles like soldiers, attendants, or servants. In Taiwan, the Ministry of National Defense of the Republic of China runs a national Peking opera training school.

Visual Elements of Peking Opera

Peking opera performers use four main skills:

- Song: Singing with music.

- Speech: Speaking lines.

- Dance-acting: This includes pure dance, acting without words (pantomime), and all other types of dance.

- Combat: This involves both acrobatics and fighting with weapons.

All these skills are expected to be performed smoothly and easily.

Beauty in Every Movement

Peking opera, like other traditional Chinese arts, focuses on meaning rather than being perfectly realistic. The main goal for performers is to make every movement beautiful. In training, performers are strongly criticized if their movements lack beauty. Performers also learn to combine the different parts of Peking opera. The four skills are not separate. They should be used together in one performance. One skill might be more important at certain times, but other actions should not stop.

Tradition is very important in this art form. Gestures, settings, music, and character types all follow old rules. This includes movement rules that tell the audience what is happening. For example, walking in a big circle always means traveling a long distance. A character fixing their costume and headdress means an important character is about to speak. Some rules are easier to understand, like pretending to open and close doors or climb stairs.

Many performances show everyday actions. But to make them beautiful on stage, these actions are made into a special style. Peking opera does not try to show reality exactly. Experts compare Peking opera's ideas to the "imitation" found in Western plays. Peking opera should suggest things, not just copy them. The real-life parts of scenes are removed or styled to better show feelings and characters.

The most common styling method in Peking opera is "roundness." Every movement and pose is carefully done to avoid sharp angles and straight lines. If a character looks at something above them, their eyes will move in a circle from low to high before looking at the object. If a character points to something on the right, they will sweep their hand in an arc from left to right. This avoidance of sharp angles also applies to moving in space. Turning around often looks like a smooth, S-shaped curve. All these beauty rules are also part of other performance elements.

Stages and Costumes

Peking opera stages have traditionally been square platforms. The action on stage can usually be seen from at least three sides. A special embroidered curtain called a shoujiu divides the stage into two parts. Musicians are visible to the audience in the front part of the stage. Old Peking opera stages were built higher than the audience's view. But some modern stages have higher audience seating. Viewers always sit south of the stage. So, north is the most important direction in Peking opera. Performers will immediately move to "center north" when they enter. All characters enter from the east and leave from the west.

Peking opera uses very few props because it is so symbolic. This has been a tradition for 700 years in Chinese performance. The presence of large objects is often shown through special rules. The stage will almost always have a table and at least one chair. These can become many different things, like a city wall, a mountain, or a bed. Smaller objects are often used to show a bigger, main object. For example, a whip means a horse, and an oar means a boat.

The length and structure of Peking opera plays can vary a lot. Before 1949, zhezixi (short plays or scenes from longer plays) were often performed. These plays usually focused on one simple situation. Or they showed scenes that used all four main Peking opera skills to show how talented the performers were. This style is less common now, but one-act plays are still performed. These short works, and individual scenes in longer plays, show an emotional journey from start to finish. A full-length play usually has 6 to 15 or more scenes. The whole story in these longer works is told by switching between different types of scenes. Plays will go back and forth between civil (peaceful) and martial (fighting) scenes, or scenes with good guys and bad guys. There are several major scenes in a long play that follow the emotional journey. These are the scenes usually picked for later zhezixi productions. Some very complex plays might even have an emotional journey from one scene to the next.

Because there are so few props, costumes are very important in Peking opera. Costumes first show the character's rank.

- Emperors and their families wear yellow robes.

- High-ranking officials wear purple.

- The robe for these two classes is called a mang, or python robe. It is very fancy, with bright colors and rich embroidery, often with a dragon design.

- Important or good people wear red.

- Lower-ranking officials wear blue.

- Young characters wear white.

- Old people wear white, brown, or olive.

- All other men wear black.

For formal events, lower officials might wear the kuan yi. This is a simple gown with embroidered patches on the front and back. All other characters, and officials on informal occasions, wear the chezi. This is a basic gown with different amounts of embroidery and no special belt to show rank. All three types of gowns have water sleeves. These are long, flowing sleeves that can be flicked and waved like water to help with emotional gestures. Minor characters with no rank wear simple clothes without embroidery. Hats are designed to match the costume and usually have similar embroidery. Shoes can have high or low soles. High soles are for high-ranking characters, and low soles are for low-ranking or acrobatic characters.

Stage Props (Qimo)

Qimo is the name for all stage props and some simple decorations. This term first appeared in the Jin dynasty (266–420). Qimo includes everyday items like candlesticks, lanterns, fans, handkerchiefs, brushes, paper, ink, and tea sets. Props also include sedan chairs, vehicle flags, oars, and horsewhips, as well as weapons.

Various items are also used to show environments. For example, cloth backdrops can represent cities. Curtains, flags, table covers, and chair covers are also used. Traditional qimo are not just copies of real items. They are also works of art themselves.

Flags are often used on stage.

- A square flag with the Chinese character for "marshal" on it, or a rectangular flag with "commander" on it, shows where army camps and commanders are.

- A flag with an army's name on it also shows its location.

- There are also flags for water, fire, wind, and vehicles. Actors shake these flags to show waves, fire, wind, or moving vehicles.

Sounds of Peking Opera

How Voices are Used

Singing in Peking opera has "four levels of song":

- Songs with music.

- Reciting verses.

- Talking in prose (like regular speech).

- Non-verbal sounds (like sighs or laughs).

This idea of different voice levels creates a smooth flow between singing and speaking. The three basic ways to use your voice are:

- Using your breath (yongqi).

- Clear pronunciation (fayin).

- Special Peking opera pronunciation (shangkouzi).

In Chinese opera, breath comes from the stomach muscles. Performers follow the rule that "strong, centered breath moves the melodies." They imagine breath moving up through a central space from their lower stomach to the top of their head. This "space" must always be controlled. Performers learn special ways to control both breathing in and out.

The two main ways to breathe in are "exchanging breath" (huan qi) and "stealing breath" (tou qi). "Exchanging breath" is a slow, calm way to breathe out old air and breathe in new. It's used when the performer has time, like during music or when another character is speaking. "Stealing breath" is a quick intake of air without breathing out first. It's used during long speeches or songs when a pause would be bad. Both techniques should be invisible to the audience. They should only take in the exact amount of air needed. The most important rule for breathing out is "saving the breath" (cun qi). Breath should not be used up all at once. Instead, it should be released slowly and evenly. Most songs and some speeches have exact marks for when to "exchange" or "steal" breath.

Pronunciation means shaping the throat and mouth to make the right vowel sound. It also means clearly saying the first consonant. There are four basic shapes for the throat and mouth, for four vowel types. There are five ways to say consonants, one for each type.

Some words (Chinese characters) have special pronunciations in Peking opera. This is because of the mix with regional styles and kunqu as Peking opera developed. For example, 你 ('you') might be said li, like in the Anhui dialect, instead of the usual ni. 我 ('I'), usually wo, becomes ngo, like in the Suzhou dialect. Also, some words are changed to make them easier to perform or to add variety to the voice. For example, zhi, chi, shi, and ri sounds are hard to sing for long. So, they are performed with an extra i sound, like zhii.

These voice techniques create the two main types of sounds in Peking opera: stage speech and song.

Stage Speech

Peking opera uses both Classical Chinese and Modern Standard Chinese, with some slang added for flavor. The character's social status decides what kind of language is used. Peking opera has three main types of stage speech (nianbai, 念白):

- Prose speeches: Monologues and dialogues make up most plays. They move the story forward or add humor. They are usually short and use everyday language. But they also have rhythm and music, created by how each sound is said and how speech tones are used. In the early days, prose speeches were often made up on the spot. Chou (clown) performers still do this today.

- Classical poetry quotes: This type is rarely used. Plays might have one or two quotes from classical Chinese poetry, or none at all. These quotes are usually meant to make a scene more powerful. However, Chou and playful Dan characters might misquote or misunderstand these lines, which creates a funny effect.

- Conventionalized stage speeches (chengshi nianbai): These are fixed phrases that mark important changes. When a character first enters, they give an 'entrance speech' (shangchang) or 'self-introduction speech' (zi bao jiamen). This includes a short poem, a scene-setting poem, and a prose scene-setting speech, in that order. The style of these speeches comes from older Chinese opera forms. Another fixed speech is the exit speech, often a poem followed by a spoken line. A supporting character usually gives this speech, describing their situation and feelings. Finally, there's the summary speech, where a character uses prose to tell the story up to that point. These speeches came about because of the zhezixi tradition of performing only parts of a longer play.

Song in Peking Opera

There are six main types of song lyrics in Peking opera: emotional, critical, storytelling, descriptive, argumentative, and "shared space separate sensations" lyrics. Each type uses the same basic song structure. They only differ in the kind and level of emotions they show. Lyrics are written in pairs of lines (lian), with two lines (ju) each. Lines can have ten characters or seven characters. They are further divided into three pauses (dou), usually in a 3-3-4 or 2-2-3 pattern. Lines can have extra characters added to make the meaning clearer. Rhyme is very important, with thirteen different rhyme groups. Song lyrics also use the tones of Mandarin Chinese in ways that sound good and show the right meaning and emotion. The first and second of China's four tones are called 'level' (ping) tones in Peking opera. The third and fourth are called 'oblique' (ze). The last line of every pair of lines in a song ends with a level tone.

Songs in Peking opera follow a set of common beauty rules. Most songs are within a range of an octave and a fifth (like a musical scale). A high pitch is seen as beautiful. So, performers sing songs at the very top of their vocal range. Because of this, the idea of a song's key is only a technical tool for the performer. Different performers in the same show might sing in different keys. This means the musicians have to constantly retune their instruments or switch with other players. Elizabeth Wichmann describes the ideal basic sound for Peking opera songs as a "controlled nasal tone." Performers use a lot of vocal vibrato (a slight wavering in pitch) during songs. This vibrato is "slower" and "wider" than what is used in Western performances. The Peking opera ideal for songs is summed up by the saying zi zheng qiang yuan. This means the words should be said clearly and precisely, and the melodies should be flowing, or "round."

Music and Instruments

The music for a Peking opera performance usually comes from a small group of traditional melodic and percussion instruments. The main melodic instrument is the jinghu. This is a small, high-pitched, two-string fiddle. The jinghu is the main instrument that plays along with performers during songs. The accompaniment is heterophonic. This means the jinghu player follows the basic shape of the song's melody but adds their own pitches and other elements. The jinghu often plays more notes than the performer sings, and it plays them an octave lower. During practice, the jinghu player creates their own special version of the song's melody. But they must also be able to change their playing quickly if the performer improvises. So, the jinghu player must be able to change their performance without warning to properly support the performer.

Another instrument is the yueqin, a round, plucked string instrument. Percussion instruments include the daluo, xiaoluo, and naobo. The person playing the gu and ban (a small, high-pitched drum and clapper) is the conductor of the whole music group.

The two main music styles of Peking opera, Xipi and Erhuang, used to be subtly different.

- In the Xipi style, the strings of the jinghu are tuned to A and D. The melodies in this style are very broken up. This might be because the style came from the high and loud melodies of Qinqiang opera in northwestern China. It is often used for happy stories.

- In Erhuang, the strings are tuned to C and G. This reflects the low, soft, and sad folk tunes from south-central Hubei province, where the style began. So, it is used for lyrical (emotional) stories.

Both music styles have a standard rhythm of two beats per bar. They share six different speeds (tempos):

- manban (a slow speed)

- yuanban (a standard, medium-fast speed)

- kuai sanyan ('leading beat')

- daoban ('leading beat')

- sanban ('rubato beat' - flexible speed)

- yaoban ('shaking beat')

The xipi style also has unique tempos, like erliu ('two-six') and kuaiban (a fast speed). Of these, yuanban, manban, and kuaiban are most common. The speed at any time is controlled by a percussion player who acts as the director. Erhuang has been seen as more improvisational, and Xipi as more calm. Over time, and because different groups have different standards, the two styles may have become more similar today.

The melodies played by the instruments fall into three main groups:

- Arias: These are the main songs. Peking opera arias are divided into Erhuang and Xipi types. An example is wawa diao, a Xipi aria sung by a young Sheng to show strong emotion.

- Fixed-tune melodies (qupai): These are instrumental tunes that serve many purposes. Examples include the 'Water Dragon Tune' (shui long yin), which usually means an important person is arriving. 'Triple Thrust' (ji san qiang) might signal a feast or party.

- Percussion patterns: These patterns add meaning to the music, similar to fixed-tune melodies. For example, there are up to 48 different percussion patterns that play when characters enter the stage. Each one tells you about the entering character's rank and personality.

Stories and Plays

Peking opera has almost 1,400 plays. Most stories come from historical novels or traditional tales about civil, political, and military struggles. Early plays were often adapted from older Chinese theater styles, like kunqu. Almost half of the 272 plays listed in 1824 came from older styles.

Plays are often sorted in different ways. Two traditional methods have been used since Peking opera began:

- Civil plays: These focus on relationships between characters. They feature personal, family, and romantic situations. Singing is often used to show emotion in these plays.

- Martial plays: These focus more on action and fighting skills. They use different types of performers. Martial plays mostly feature young sheng, jing, and chou. Civil plays need more older roles and dan.

Plays are also classified as either daxi (serious) or xiaoxi (light). The performance styles and performers used in serious and light plays are very similar to those in martial and civil plays. Of course, the idea of combining different elements often leads to plays that mix these types.

Since 1949, a more detailed way of classifying plays has been used. This is based on the play's topic and when it was created:

- chuantongxi: Traditional plays performed before 1949.

- xinbian de lishixi: Historical plays written after 1949. These were not produced during the Cultural Revolution, but they are a major focus today.

- xiandaixi: Contemporary plays. The topics of these plays come from the 1900s and beyond. Modern productions are often experimental and might include Western influences.

In the second half of the 1900s, Western stories have been increasingly adapted for Peking opera. The works of Shakespeare have been especially popular. This trend of adapting Shakespeare has spread to all forms of Chinese theater. Peking opera, in particular, has seen versions of A Midsummer Night's Dream and King Lear, among others.

In 2017, Li Wenrui wrote in China Daily that 10 classic Peking opera plays are:

- The Drunken Concubine

- Monkey King

- Farewell My Concubine

- A River All Red

- Wen Ouhong's Unicorn Trapping Purse (a famous work by Peking Opera master Chen Yanqiu)

- White Snake Legend

- The Ruse of the Empty City (from Romance of the Three Kingdoms)

- Du Mingxin's Female Generals of the Yang Family

- Wild Boar Forest

- The Phoenix Returns Home

Peking Opera in Movies

Peking opera and its unique style have appeared in many Chinese films. It was often used to show a special "Chineseness," especially when compared to Japanese films. Fei Mu, a director from before the Communist era, used Peking opera in several plays. Sometimes he put it into Western-style, realistic plots. King Hu, a later Chinese film director, used many of Peking opera's formal rules in his movies. For example, he showed how music, voice, and gestures work together.

In the 1993 film Farewell My Concubine by Chen Kaige, Peking opera is central to the main characters' goals and their love story. However, some people have criticized the film's portrayal of Peking opera as being too simple.

See also

In Spanish: Ópera de Pekín para niños

In Spanish: Ópera de Pekín para niños

- Yunbai

- China National Peking Opera Company

- Zheng Yici Peking Opera Theatre

- Huguang Guild Hall

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |