Noh facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Nōgaku Theater |

|

|---|---|

|

UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage

|

|

Noh performance at Itsukushima Shrine

|

|

| Country | Japan |

| Domains | Performing arts |

| Reference | 12 |

| Region | Asia and the Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2008 (3rd session) |

| List | Representative |

|

|

Noh (能, Nō, derived from the Sino-Japanese word for "skill" or "talent") is a very old Japanese dance-drama. People have been performing it since the 1300s. It was created by Kan'ami and his son Zeami. Noh is the oldest major theater art that is still performed regularly today.

Sometimes, people use the words Noh and nōgaku to mean the same thing. But nōgaku actually includes both Noh and kyōgen. A full nōgaku show traditionally had several Noh plays with funny kyōgen plays in between. Today, it's more common to see a shorter show with two Noh plays and one kyōgen piece. Sometimes, a special ritual performance called Okina is shown at the very beginning.

Noh plays often tell stories from old Japanese literature. These stories usually feature a supernatural being who turns into a human hero. This hero then tells a story. Noh performances use special masks, costumes, and props. They are based on dance and need highly trained actors and musicians. Actors show feelings mostly through special, traditional movements. The famous masks show different characters like ghosts, women, gods, and demons. The words of the plays were written in late middle Japanese. They describe the everyday lives of people from the 1100s to the 1500s. Noh focuses a lot on tradition, not on new ideas. It follows very strict rules set by the iemoto system.

Contents

History of Noh Theater

How Noh Began

The Japanese word for Noh (能) means "skill," "craft," or "talent." It especially refers to performing arts. The word Noh can be used alone, or with gaku (楽), which means entertainment or music. Together, they form nōgaku. Noh is a very old tradition that many people still value today. When we say "Noh" by itself, we mean the type of theater that started from sarugaku in the mid-1300s. It is still performed now.

One of the oldest forms of entertainment that led to Noh and kyōgen was sangaku. This came to Japan from China in the 700s. Back then, sangaku included many types of shows. These were acrobats, singing, dancing, and funny skits. Over time, it mixed with other Japanese art forms. Different parts of sangaku, along with dengaku (farm celebrations), sarugaku (popular shows with acrobatics and mime), shirabyōshi (dances by women in the Imperial Court), gagaku (court music and dance), and kagura (ancient Shinto dances), all helped Noh and kyōgen to develop.

Some studies show that Noh actors in the 1300s came from families who specialized in performing arts. The Konparu School is thought to be the oldest Noh tradition. Legend says it was started by Hata no Kawakatsu in the 500s. However, historians generally agree that Bishaō Gon no Kami (Komparu Gonnokami) founded the Konparu school in the 1300s. The Konparu school came from a sarugaku group. This group was active at Kasuga-taisha and Kofuku-ji in Yamato Province.

Another idea is that Noh started with people who were trying to gain a higher social status. They did this by performing for powerful people, like the new samurai rulers. When the shogunate moved from Kamakura to Kyoto in the early Muromachi period, the samurai class became stronger. This also made the link between the shogunate and the court stronger. Noh became the shōgun’s favorite art form. Because of this, Noh became a respected court art. In the 1300s, with strong support from shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, Zeami made Noh the most important theater art of that time.

How Kan'ami and Zeami Shaped Noh

In the 1300s, during the Muromachi period, Kan'ami Kiyotsugu and his son Zeami Motokiyo changed many traditional performing arts. They created Noh in a new way, making it very similar to the Noh we see today. Kan'ami was a famous actor who could play many different roles. He could play graceful women, young boys, and strong men. When Kan'ami first showed his work to the 17-year-old Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, Zeami was a child actor, about 12 years old. Yoshimitsu loved Zeami. Because of this, Noh was performed often for Yoshimitsu after that.

Konparu Zenchiku was the great-grandson of Bishaō Gon no Kami, who founded the Konparu school. He was also married to Zeami's daughter. He added parts of waka (poetry) to Zeami's Noh, helping it grow even more.

By this time, four of the five main Noh schools were created. These were the Kanze school (by Kan'ami and Zeami), the Hōshō school (by Kan'ami's older brother), the Konparu school, and the Kongō school. All these schools came from the sarugaku group in Yamato Province. The Ashikaga shogunate only supported the Kanze school among these four.

Noh in the Tokugawa Era

During the Edo period, Noh continued to be an art form for the rich and powerful. It was supported by the shōgun, the feudal lords (daimyōs), and also by wealthy commoners. While kabuki and joruri were popular with the middle class and focused on new entertainment, Noh aimed to keep its high standards and old traditions. It stayed mostly the same throughout this time. To capture the spirit of great masters' performances, every movement and position was carefully copied. This made performances generally slower and more ceremonial over time.

In this era, the Tokugawa shogunate made the Kanze school the leader of the four schools. Kita Shichidayū, a Noh actor from the Konparu school, founded the Kita school. This was the last of the five major schools to be established.

Modern Noh After the Meiji Era

When the Tokugawa shogunate ended in 1868, a new, modern government took over. This meant that Noh lost its financial support from the state. The entire world of Noh faced a big money problem. Soon after the Meiji Restoration, the number of Noh performers and stages greatly decreased.

However, support from the government was eventually regained. This was partly because Noh appealed to foreign diplomats. The groups that kept performing during the Meiji Restoration also made Noh more popular with the general public. They performed in theaters in big cities like Tokyo and Osaka.

In 1957, the Japanese Government named nōgaku an Important Intangible Cultural Property. This gives the tradition and its best performers some legal protection. The National Noh Theatre, started by the government in 1983, holds regular shows. It also offers courses to train actors for the main roles in nōgaku. In 2008, UNESCO added Noh to the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity as Nōgaku theatre.

Even though nōgaku and Noh are sometimes used to mean the same thing, the Japanese government says "nōgaku" includes both Noh plays and kyōgen plays. Kyōgen is performed between Noh plays in the same space. Compared to Noh, kyōgen uses fewer masks. It comes from funny plays, which you can see in its humorous conversations.

Women in Noh Theater

During the Edo period, the rules for Noh groups became very strict. This mostly kept women from performing Noh. Only a few women sang in less important situations. Later, in the Meiji Restoration, Noh performers taught wealthy people and nobles. This led to more chances for female performers, as women wanted female teachers. In the early 1900s, after women could join Tokyo Music School, the rules against women joining Noh schools and groups became less strict. In 1948, the first women joined the Nohgaku Performers' Association. In 2004, the first women joined the Association for Japanese Noh Plays. In 2007, the National Noh Theatre started to have regular shows by female performers every year. By 2009, there were about 1200 male and 200 female professional Noh performers.

Jo-ha-kyū: The Flow of Noh

The idea of jo-ha-kyū guides almost every part of Noh. This includes how a program of plays is put together, how each play is structured, the songs and dances within plays, and the basic rhythms of each Noh performance. Jo means beginning, ha means breaking, and kyū means rapid or urgent. This idea came from gagaku, which is ancient court music. It was used to show a tempo that slowly gets faster. This concept was then used in many Japanese traditions, including Noh, tea ceremony, poetry, and flower arranging.

Jo-ha-kyū is used in the traditional five-play Noh program. The first play is jo, the second, third, and fourth plays are ha, and the fifth play is kyū. In fact, the five types of plays discussed below were made so that a program would show jo-ha-kyū. This happens when one play from each type is chosen and performed in order. Each play itself can be divided into three parts: the introduction, the development, and the conclusion. A play starts slowly at jo, gets a bit faster at ha, and then reaches its fastest point at kyū.

Performers and Their Roles

Actors start their training when they are very young children, usually around three years old.

Training for Noh Actors

Zeami described nine levels or types of Noh acting. The lower levels focused on movement and strong actions. The higher levels showed the "opening of a flower" and spiritual skill.

Today, there are five main schools of Noh acting for shite actors. These are the Kanze, Hōshō, Komparu, Kongō, and Kita schools. Each school has its own main family, called iemoto. This family carries the school's name and is seen as the most important. The iemoto has the power to create new plays or change old ones. Waki actors are trained in the Takayasu, Fukuou, and Hōshō schools. There are two schools that train kyōgen actors: Ōkura and Izumi. Eleven schools train the musicians, with each school focusing on one to three instruments.

The Nohgaku Performers' Association, where all professional actors are registered, strictly protects the traditions passed down from their ancestors.

Main Roles in Noh Plays

There are four main types of Noh performers: shite, waki, kyōgen, and hayashi.

- Shite (仕手, シテ): This is the main character or the lead role in the plays. In plays where the shite first appears as a human and then as a ghost, the first role is called the mae-shite. The later role is called the nochi-shite.

- Shitetsure (仕手連れ, シテヅレ): This is the shite's companion. Sometimes it's shortened to tsure.

- Kōken (後見): These are stage hands, usually one to three people.

- Jiutai (地謡): This is the chorus, usually with six to eight people.

- Waki (脇, ワキ): This role is the opposite or partner to the shite.

- Wakitsure (脇連れ, ワヅレ): This is the companion of the waki.

- Kyōgen (狂言): These actors perform aikyōgen, which are short, funny parts during the plays. Kyōgen actors also perform in separate plays between Noh plays.

- Hayashi (囃子) or hayashi-kata (囃子方): These are the musicians who play the four instruments used in Noh theater. These are the flute (笛, fue), the hip drum (大鼓, ōtsuzumi) or ōkawa (大皮), the shoulder-drum (小鼓, kotsuzumi), and the stick-drum (太鼓, taiko). The flute used for Noh is specially called nōkan or nohkan (能管).

A typical Noh play always has a chorus, an orchestra, and at least one shite and one waki actor.

Elements of a Noh Performance

Noh performances combine many elements into one unique style. Each part has been refined over generations. This follows the main Buddhist, Shinto, and simple ideas of Noh's beauty.

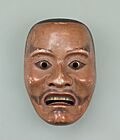

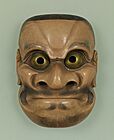

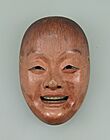

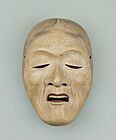

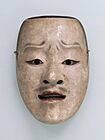

Noh Masks

Noh masks (能面 nō-men or 面 omote) are carved from blocks of Japanese cypress (檜 "hinoki"). They are painted with natural colors on a base of glue and crushed seashell. There are about 450 different masks, but they are mostly based on sixty main types. All of them have special names. Some masks are common and used in many plays. Others are very specific and might only be used in one or two plays. Noh masks show the character's gender, age, and social status. By wearing masks, actors can play young people, old men, women, or non-human characters like gods or demons. Only the shite, the main actor, wears a mask in most plays. However, the tsure might also wear a mask in some plays.

Even though a mask covers an actor's face, it doesn't mean there are no facial expressions. Instead, the mask helps to make the expressions very stylish and traditional. It also helps the audience use their imagination. By using masks, actors can show feelings in a more controlled way through their movements and body language. Some masks use light to show different emotions. If the actor tilts their head slightly upward, the mask catches more light. This makes it look like the character is laughing or smiling. If they tilt it downward, the mask looks sad or angry.

Noh masks are very important to Noh families and groups. The powerful Noh schools own the oldest and most valuable Noh masks. These are rarely seen by the public. The oldest mask is supposedly a hidden treasure of the Konparu school. Legend says it was carved by the famous Prince Shōtoku (572–622) over a thousand years ago. While this legend might not be historically true, the story itself is very old. It was first written down in Zeami's Style and the Flower in the 1300s. Some of the masks from the Konparu school are in the Tokyo National Museum. They are often displayed there.

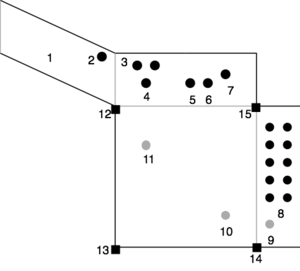

The Noh Stage

The traditional Noh stage (butai) is completely open. This allows performers and the audience to share the experience. There are no curtains to block the view. The audience can see every actor, even before they enter or after they leave the main stage (honbutai). The theater itself is seen as special and treated with great respect by both performers and the audience.

One of the most recognizable features of a Noh stage is its separate roof. This roof hangs over the stage even in indoor theaters. It is supported by four pillars. The roof shows how sacred the stage is. Its design comes from the worship pavilion (haiden) or sacred dance pavilion (kagura-den) of Shinto shrines. The roof also brings the theater space together. It clearly defines the stage as a special structure.

The pillars supporting the roof have names. They are shitebashira (main character's pillar), metsukebashira (gazing pillar), wakibashira (secondary character's pillar), and fuebashira (flute pillar). They are named clockwise from the back right of the stage. Each pillar is connected to the performers and their actions.

The stage is made entirely of unfinished hinoki, which is Japanese cypress. It has almost no decorations. The writer Tōson Shimazaki said that "on the stage of the Noh theatre there are no sets that change with each piece. Neither is there a curtain. There is only a simple panel (kagami-ita) with a painting of a green pine tree. This makes it seem like anything that could provide shade has been removed. To break such sameness and make something happen is not easy."

Another special part of the stage is the hashigakari. This is a narrow bridge at the back right of the stage. Actors use it to enter the stage. Hashigakari means "suspension bridge." It suggests something airy that connects two different worlds on the same level. The bridge symbolizes the magical nature of Noh plays. In these plays, ghosts and spirits from other worlds often appear. In contrast, the hanamichi in Kabuki theaters is literally a path (michi). It connects two spaces in one world, so it has a completely different meaning.

Costumes in Noh

Noh actors wear silk costumes called shozoku (robes). They also use wigs, hats, and props like the fan. Noh robes are truly works of art. They have striking colors, detailed textures, and complex weaving and embroidery. The costumes for the shite (main actor) are especially fancy. They are shimmering silk brocades. The costumes for the tsure (companion), wakizure (waki's companion), and aikyōgen (interlude actor) are less grand.

For many centuries, Noh costumes copied the clothes characters would really wear. This was Zeami's idea. So, a courtier would wear formal robes, and a peasant would wear everyday clothes. But in the late 1500s, the costumes became more stylized. They started to follow certain symbolic and artistic rules. During the Edo (Tokugawa) period, the fancy robes given to actors by nobles and samurai in the Muromachi period were developed into the costumes we see today.

The musicians and chorus usually wear formal montsuki kimono. These are black and have five family crests. They wear them with either hakama (a skirt-like garment) or kami-shimo. Kami-shimo is a mix of hakama and a vest with big shoulders. Finally, the stage attendants wear plain black clothes. This is much like stagehands in modern Western theater.

Props in Noh

Noh uses props in a very simple and artistic way. The most common prop is the fan. All performers carry a fan, no matter their role. Chorus singers and musicians might carry their fan in hand when they come on stage. Or they might tuck it into their obi (sash). The fan is usually placed next to the performer when they take their spot. It is often not picked up again until they leave the stage. During dance parts, the fan is typically used to represent any hand-held prop. This could be a sword, a wine jug, a flute, or a writing brush. The fan can represent different objects during one play.

When props other than fans are used, they are usually brought on or taken off stage by kuroko. These are like stage crew in modern theater. Like their Western counterparts, Noh stage attendants traditionally dress in black. But unlike in Western theater, they might appear on stage during a scene. Or they might stay on stage for the whole performance. In both cases, the audience can see them clearly. The all-black costume of kuroko means they are not part of the action on stage. They are effectively invisible.

Set pieces in Noh, like boats, wells, altars, and bells, are usually carried onto the stage before the act where they are needed. These props are usually just outlines to suggest real objects. However, the large bell is a special exception to most Noh prop rules. It is designed to hide the actor and allow a costume change during the kyōgen interlude.

Chant and Music in Noh

Noh theater has a chorus and a hayashi ensemble (Noh-bayashi 能囃子). Noh is a chanted drama. Some people have called it "Japanese opera". However, the singing in Noh uses a limited range of notes. It has long, repeated parts with a small change in loudness. The words are poetic. They use a lot of the Japanese seven-five rhythm, which is common in almost all Japanese poetry. The language is simple, but full of hints and references. The singing parts of Noh are called "Utai" and the speaking parts are called "Kataru". The music has many silent spaces (ma) between the actual sounds. These silent spaces are actually seen as the most important part of the music. Besides utai, the Noh hayashi ensemble has four musicians, also known as the "hayashi-kata." This includes three drummers who play the shime-daiko, ōtsuzumi (hip drum), and kotsuzumi (shoulder drum). There is also a nohkan flutist.

The chanting is not always done "in character." This means the actor might sometimes speak lines or describe events from another character's point of view. Or they might even speak as a narrator who is not involved in the story. This does not break the flow of the performance. Instead, it fits with the otherworldly feeling of many Noh plays, especially those called mugen.

Types of Noh Plays

There are about 2000 Noh plays known today. Around 240 of these are still performed by the five existing Noh schools. The plays performed today are greatly influenced by what rich people liked during the Tokugawa period. They don't necessarily show what was popular among common people. There are several ways to group Noh plays.

Play Subjects

All Noh plays can be put into three main groups.

- Genzai Noh (現在能, "present Noh"): These plays have human characters. Events happen in a straight timeline within the play.

- Mugen Noh (夢幻能, "supernatural Noh"): These plays involve supernatural worlds. They feature gods, spirits, ghosts, or phantoms as the shite (main character). Time often doesn't pass in a straight line. The action might jump between two or more time periods, including flashbacks.

- Ryōkake Noh (両掛能, "mixed Noh"): These are less common. They are a mix of the above. The first act is Genzai Noh, and the second act is Mugen Noh.

While Genzai Noh uses conflicts to drive stories and show feelings, Mugen Noh focuses on using flashbacks of the past and dead characters to bring out emotions.

Performance Styles

Also, all Noh plays can be grouped by their style.

- Geki Noh (劇能): This is a drama that focuses on moving the plot forward and telling the story.

- Furyū Noh (風流能): This is more of a dance piece. It has detailed stage actions, often with acrobatics, props, and many characters.

Themes of Noh Plays

All Noh plays are divided by their themes into five categories. This way of grouping is the most useful. It is still used today for choosing plays for a formal program. Traditionally, a formal program of five plays includes one play from each group.

- Kami mono (神物, god plays) or waki Noh (脇能): These usually feature the shite as a god. They tell the mythical story of a shrine or praise a god. Many have two acts. The god takes a human form in disguise in the first act. Then, in the second act, the god shows their true self. (Examples: Takasago, Chikubushima)

- Shura mono (修羅物, warrior plays) or ashura Noh (阿修羅能): These plays get their name from the Buddhist underworld. The main character appears as the ghost of a famous samurai. He asks a monk for salvation. The play ends with a grand re-enactment of his death scene in full war costume. (Examples: Tamura, Atsumori)

- Katsura mono (鬘物, wig plays) or onna mono (女物, woman plays): These plays show the shite in a female role. They feature some of the most beautiful songs and dances in Noh. These reflect the smooth, flowing movements of female characters. (Examples: Basho, Matsukaze)

- There are about 94 "miscellaneous" plays. These are traditionally performed in the fourth spot in a five-play program. These plays include types like kyōran mono (狂乱物, madness plays), onryō mono (怨霊物, vengeful ghost plays), genzai mono (現在物, present plays), and others. (Examples: Aya no tsuzumi, Kinuta)

- Kiri Noh (切り能, final plays) or oni mono (鬼物, demon plays): These usually feature the shite as monsters, goblins, or demons. They are often chosen for their bright colors and fast, exciting final movements. Kiri Noh is performed last in a five-play program. There are about 30 plays in this group. Most of them are shorter than plays in other categories.

Besides these five, Okina (翁) (or Kamiuta) is often performed at the very beginning of a program. This is especially true on New Year's, holidays, and other special days. It combines dance with Shinto ritual. It is considered the oldest type of Noh play.

Well-Known Noh Plays

Here are some famous plays, grouped by the Kanze school:

| Name | Kanji | Meaning | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aoi no Ue | 葵上 | Lady Aoi | 4 (misc.) |

| Aya no Tsuzumi | 綾鼓 | The Damask Drum | 4 (misc.) |

| Dōjōji | 道成寺 | Dōjō Temple | 4 (misc.) |

| Hagoromo | 羽衣 | The Feather Mantle | 3 (woman) |

| Izutsu | 井筒 | The Well Cradle | 3 (woman) |

| Matsukaze | 松風 | The Wind in the Pines | 3 (woman) |

| Sekidera Komachi | 関寺小町 | Komachi at Seki Temple | 3 (woman) |

| Shōjō | 猩々 | The Tippling Elf | 5 (demon) |

| Sotoba Komachi | 卒都婆小町 | Komachi at the Gravepost | 3 (woman) |

| Takasago | 高砂 | At Takasago | 1 (deity) |

| Yorimasa | 頼政 | Yorimasa | 2 (warrior) |

Noh's Influence in the West

Many Western artists have been inspired by Noh.

Theater Artists

- Eugenio Barba: Japanese Noh Masters Hideo Kanze and Hisao Kanze taught about Noh at Barba's Theater Laboratory from 1966 to 1972. Barba mainly studied the physical parts of Noh.

- Samuel Beckett: Some think Beckett's Waiting for Godot is a funny version of Noh, especially Kami Noh. In Kami Noh, a god or spirit appears to a secondary character.

- Bertolt Brecht: Brecht started reading Japanese plays in the mid-1920s. By 1929, he had read at least 20 Noh plays translated into German. Brecht's Der Jasager is based on a Noh play called Taniko. Brecht himself said Die Massnahme was also based on a Noh play.

- Peter Brook: Yoshi Oida, a Japanese actor trained in Noh, started working with Brook in 1968 for their play The Tempest. Oida later joined Brook's theater company.

- Paul Claudel: Claudel learned about Noh when he was the French Ambassador to Japan. His opera Christophe Colomb clearly shows Noh's influence.

- Jacques Copeau: In 1923, Copeau worked on a Noh play, Kantan, without ever seeing a Noh play. He later praised Noh theater in writing after finally seeing a performance in 1930.

- Guillaume Gallienne: He directed Deguchinashi (Huis-Clos) by Jean-Paul Sartre. This was a Noh version of Sartre's play, performed in Tokyo in 2006.

- Jacques Lecoq: The Physical theatre taught at Lecoq's school is influenced by Noh.

- Eugene O'Neill: O'Neill's plays The Iceman Cometh, Long Day's Journey into Night, and Hughie have similarities to Noh plays.

- Thornton Wilder: Wilder showed interest in Noh in his "Preface” to Three Plays. His sister also confirmed his interest. Wilder's play Our Town uses parts of Noh, like a simple plot, symbolic characters, and ghosts.

Composers

- William Henry Bell: An English composer, Bell wrote music for modern versions of several Noh plays.

- Benjamin Britten: Britten visited Japan in 1956 and saw Japanese Noh plays for the first time. He called them "some of the most wonderful drama I have ever seen." Their influence can be heard in his ballet The Prince of the Pagodas (1957) and later in two of his "Parables for Church Performance": Curlew River (1964) and The Prodigal Son (1968).

- David Byrne: Byrne discovered Noh while touring Japan with Talking Heads. He was inspired by Noh's very stylized ways, which were different from Western theater's focus on realism.

- Harry Partch: Partch called his work Delusion of the Fury a "ritualistic web." It mixes Japanese Noh theater, Ethiopian folk stories, Greek drama, and his own ideas. Delusion of the Fury includes two Noh plays, Atsumori and Ikuta, in its story.

- Karlheinz Stockhausen: The story for Stockhausen's opera cycle Licht ("Light") is based on myths from many cultures, including Japanese Noh theater.

- Iannis Xenakis: Xenakis admired Noh for its formal rituals and complex movements.

Poets

- W. B. Yeats: Yeats wrote an essay on Noh in 1916. He wrote four plays that were greatly influenced by Noh. These plays were the first to use ghosts or supernatural beings as the main characters. The plays are At the Hawk's Well, The Dreaming of the Bones, The Words upon the Window-Fane, and Purgatory.

Special Noh Terms

Zeami and Zenchiku described several special qualities. These are important for truly understanding Noh as an art form.

- Hana (花, flower): Zeami said that after you master everything, the "flower that never vanishes" remains. A true Noh performer tries to create a special connection with the audience, like growing flowers. Hana is meant to be enjoyed by everyone. It comes in two forms: individual hana (the beauty of youth) and "true hana" (the beauty of creating and sharing perfect art).

- Yūgen (幽玄, profound sublimity): Yūgen is a valued idea in many Japanese arts. It originally meant elegance or grace in waka. In Noh, yūgen means a deep, unseen beauty of a spiritual world. This includes the sad beauty found in sorrow and loss.

- Rōjaku (老弱): Rō means old, and jaku means calm and quiet. Rōjaku is the final stage for a Noh actor. In this stage, the actor removes all unnecessary actions or sounds. Only the true essence of the scene or action remains.

- Kokoro or shin (both 心): These mean "heart" or "mind." In Noh, kokoro refers to the "mind" that Zeami spoke of. To develop hana, an actor must reach a state of no-mind, or mushin.

- Myō (妙): This is the "charm" of an actor who performs perfectly. They become their role without seeming to imitate it.

- Monomane (物真似, imitation or mimesis): This is when a Noh actor tries to accurately show the movements of their role. It's not just for artistic reasons. Monomane is sometimes compared to yūgen. They are like two ends of a scale, not completely separate ideas.

- Kabu-isshin (歌舞一心, "song-dance-one heart"): This idea says that song (including poetry) and dance are two parts of the same whole. A Noh actor tries to perform both with a complete unity of heart and mind.

Noh Theaters Today

Noh is still performed regularly today. You can see it in public theaters and private theaters, mostly in big cities. There are more than 70 Noh theaters across Japan. They show both professional and amateur performances.

Public theaters include National Noh Theatre (Tokyo), Nagoya Noh Theater, Osaka Noh Theater, and Fukuoka Noh Theater. Each Noh school has its own permanent theater. Examples are Kanze Noh Theater (Tokyo), Hosho Noh Theater (Tokyo), Kongo Noh Theater (Kyoto), Nara Komparu Noh Theater (Nara), and Taka no Kai (Fukuoka). Also, there are many local theaters throughout Japan. These host touring professional groups and local amateur groups. In some areas, unique regional Noh, like Ogisai Kurokawa Noh, have developed their own schools separate from the five traditional ones.

How to Be a Good Audience Member

Audience behavior in Noh is generally similar to formal Western theater. The audience watches quietly. There are no subtitles, but some audience members follow along using a script. Since there are no curtains on the stage, the performance starts when the actors enter and ends when they leave. The house lights usually stay on during the show. This creates a close feeling and a shared experience between the performers and the audience.

At the end of the play, the actors slowly leave the stage. The most important actor leaves first, with gaps between actors. While they are on the bridge (hashigakari), the audience claps gently. Clapping stops between actors and starts again as the next actor leaves. Unlike in Western theater, there is no bowing. Actors do not return to the stage after leaving. A play might end with the shite character leaving the stage as part of the story. In this case, you clap as the character exits.

During the break, tea, coffee, and wagashi (Japanese sweets) might be served in the lobby. In the Edo period, when Noh shows lasted all day, bigger makunouchi bentō (幕の内弁当, "between-acts lunchbox") were served. On special occasions, after the performance, ceremonial sake (o-miki) might be served in the lobby on the way out, just like in Shinto rituals.

The audience sits in front of the stage, to the left side of the stage, and in the front-left corner. These are in order of best view to least best. The metsuke-bashira pillar might block some of the stage. However, the actors are mostly at the corners, not the center. So, the two aisles are placed where the views of the two main actors would be blocked. This helps ensure a generally clear view no matter where you sit.

See Also

In Spanish: Nō para niños

In Spanish: Nō para niños

- Theatre of Japan

- Higashiyama culture

- Shuhari

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |