Bunraku facts for kids

Bunraku (文楽) (also known as Ningyō jōruri (人形浄瑠璃)) is a special kind of traditional Japanese puppet theatre. It started in Osaka in the early 1600s and is still performed today.

Three main types of performers bring a bunraku show to life:

- The Ningyōtsukai or Ningyōzukai (the puppeteers)

- The tayū (the chanters or narrators)

- The shamisen musicians

Sometimes, other instruments like taiko drums are also used. The singing and shamisen playing together is called jōruri. The Japanese word for puppet or doll is ningyō.

Contents

History of Bunraku Theatre

Bunraku has a long history, going back to the 1500s. But its modern style began around the 1680s. It became very popular after a writer named Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653–1724) started working with a chanter named Takemoto Gidayu (1651–1714). Takemoto Gidayu opened the Takemoto puppet theatre in Osaka in 1684.

At first, the name bunraku only referred to a specific theatre. This theatre opened in Osaka in 1805. It was named the Bunrakuza after Uemura Bunrakuken (植emura Bunrakuken, 1751–1810). He was a puppeteer from Awaji Island who helped make puppet theatre popular again in the early 1700s.

How Bunraku Performances Work

The puppets used in Osaka are usually a bit smaller. But puppets from the Awaji tradition can be very large. This is because shows in Awaji are often held outdoors.

Making the Puppets

Special artists carve the heads and hands of the puppets. The puppeteers often build the bodies and make the costumes themselves. Puppet heads can be very clever and complex. For plays about supernatural things, a puppet's face might even change quickly into a demon's face! Simpler heads can have eyes that move or close, and mouths, noses, and eyebrows that move too.

All the movements for the puppet's head are controlled by a handle. This handle goes down from the puppet's neck. The main puppeteer puts their left hand inside the puppet's chest to reach these controls.

Puppeteers and Their Roles

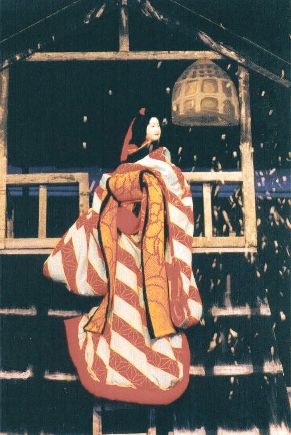

Each main puppet needs three puppeteers to make it move. These puppeteers perform in front of the audience. They usually wear black robes. Most of the time, all puppeteers also wear black hoods. However, in some traditions, like at the National Bunraku Theater, the main puppeteer does not wear a hood. This style is called dezukai. The shape of the hoods can also change depending on the puppeteer's school.

The main puppeteer, called the omozukai, uses their right hand to control the puppet's right hand. They use their left hand to control the puppet's head. The left puppeteer, known as the hidarizukai or sashizukai, moves the puppet's left hand. They do this with their own right hand, using a control rod. A third puppeteer, the ashizukai, moves the puppet's feet and legs.

Puppeteers start their training by learning to move the feet. Then they move on to the left hand. After that, they can train to be the main puppeteer. This training takes a very long time. Many artists say it can take ten years for the feet, ten years for the left hand, and ten years for secondary characters' heads before they can control a main character's head. This long training helps artists develop their skills and also helps manage who gets which role in the group.

The Chanter and Musician

Usually, one chanter tells the whole story and speaks for all the characters. They change their voice and style to sound like different characters in a scene. Sometimes, more than one chanter is used. The chanters sit next to the shamisen player. Some theatres have a spinning platform for the chanter and shamisen player. This platform rotates to bring new musicians onto the stage for the next part of the show.

The shamisen used in bunraku is a bit bigger than other types. It also has a different sound, which is lower and fuller.

Bunraku vs. Kabuki

Bunraku shares many stories and ideas with kabuki theatre. In fact, many plays were changed so they could be performed by both actors in kabuki and puppet groups in bunraku.

Bunraku focuses on the writer's story, while kabuki focuses more on the actors' performance. In bunraku, before a show, the chanter holds up the script and bows. This shows they promise to follow the story exactly. In kabuki, actors might add jokes, unplanned lines, or references to current events.

The most famous bunraku writer was Chikamatsu Monzaemon. He wrote over 100 plays. Some people call him the Shakespeare of Japan.

Bunraku groups, performers, and puppet makers are honored as "Living National Treasures" in Japan. This is part of Japan's plan to protect its culture.

Bunraku Today

The main government-supported bunraku group is at the National Bunraku Theatre in Osaka. This theatre puts on five or more shows each year. Each show runs for two to three weeks in Osaka, then moves to Tokyo. The National Bunraku Theatre also travels around Japan and sometimes to other countries.

Before the late 1800s, there were hundreds of other professional and amateur puppet groups in Japan. After World War II, the number of groups dropped to fewer than 40. Most of these groups perform only once or twice a year, often during local festivals. However, a few regional groups still perform regularly.

- The Awaji Puppet Troupe, on Awaji Island, offers daily shows. They have also toured in the United States and Russia.

- The Tonda Puppet Troupe (冨田人形共遊団) from Shiga Prefecture started in the 1830s. They have toured the United States and Australia five times. They also host programs for American university students to learn traditional Japanese puppetry.

- The Imada Puppet Troupe and the Kuroda Puppet Troupe are both in Iida, Nagano Prefecture. Both groups are over 300 years old. They perform often and help train new puppeteers. They also teach American university students in summer programs.

Interest in bunraku has even led to the first traditional Japanese puppet group in North America. Since 2003, the Bunraku Bay Puppet Troupe from the University of Missouri has performed across the United States, including at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. They have also performed in Japan with the Imada Puppet Troupe. The Center for Puppetry Arts in Atlanta, Georgia, has many bunraku puppets in its Asian collection.

Music and Song in Bunraku

The chanter/singer (tayū) and the shamisen player create the main music for traditional Japanese puppet theatre. In most shows, only one shamisen player and one chanter perform the music for each act. How well these two musicians work together makes a big difference in the show's quality.

The tayū's job is to show the feelings and personality of the puppets. The tayū not only speaks for each character but also tells the story as a narrator.

The tayū sits to the side of the stage. They show the characters' facial expressions while speaking their lines. When performing many characters at once, the tayū makes it easy to tell them apart by making their emotions and voices very clear. This also helps the audience feel the emotions more strongly.

For bunraku, a special shamisen called the futo-zao shamisen is used. It is the largest type of shamisen and has the lowest, fullest sound. Other instruments often used include flutes, especially the shakuhachi, the koto, and various percussion instruments.

Bunraku Puppets

The Puppet's Head (Kashira)

The puppet heads (kashira) are sorted into groups. These groups are based on gender, social class, and personality. Some heads are made for specific roles. Others can be used for different shows by changing their clothes and paint. The heads are repainted and prepared before each performance.

There are about 80 main types of puppet heads. The Japan Arts Council lists 129 different types.

Some of these heads have special tricks built into them. By pulling strings, the puppet's expression can change. This can show a human turning into a yōkai (strange apparition) or a onryō (vengeful spirit). For example, a head called gabu can instantly make a beautiful woman's mouth split open to her ears, grow fangs, and change her eyes to a large golden color with golden horns. This allows one head to show a woman turning into a hannya (female demon). Another head, for Tamamo-no-Mae, can instantly cover a beautiful woman's face with a kitsune (fox) mask by pulling a string.

Making the hair for the puppets is an art itself. The hair helps define the character and can show parts of their personality. The hair is made from human hair, but sometimes yak tail is added for more volume. The hair is then attached to a copper plate. To protect the puppet head, the hairstyle is finished with water and beeswax, not oil.

Puppet Costumes

A costume master designs the puppet costumes. They are made of several layers of clothing with different colors and patterns. These clothes usually include a sash, a collar, an underkimono (juban), a kimono, and an outer robe (haori or uchikake). The costumes are lined with cotton to keep them soft.

When the puppets' clothes get old or dirty, the puppeteers replace them. The process of dressing or redressing the puppets is called koshirae.

How Puppets Are Built

A puppet's frame is simple. The carved wooden kashira (head) is attached to a head grip (dogushi). This grip goes down through an opening in the puppet's shoulder. Long fabric is draped over the front and back of the shoulder board. Then, more cloth is attached. Carved bamboo creates the puppet's hips. Arms and legs are tied to the body with ropes. Puppets do not have a torso. This allows the puppeteer to move the limbs freely. The isho, or costume, is then sewn on. This covers any cloth, wood, or bamboo parts that should not be seen. Finally, a slit is made in the back of the costume. This allows the main puppeteer to hold the dogushi head stick firmly.

The Story and the Puppets

Unlike kabuki, which focuses on the main actors' performance, bunraku shows both presentation and representation. This means it tries to create a certain feeling in the audience while also expressing the writer's ideas. So, attention is given to both how the puppets look and sound, as well as the performance and the story itself. Every play starts with a short ceremony. The tayū kneels behind a small, fancy lectern. They respectfully lift their copy of the script. This shows their dedication to performing the text exactly as written. The script is also shown at the beginning of each act.

Bunraku Performers

Even though their training is complex, puppeteers often came from poor backgrounds. The kugutsu-mawashi were travelers. Because of this, they were often not accepted by the richer people in Japanese society at the time. As entertainment, the men would use small hand puppets for shows. The themes of these puppet shows often reflected the difficult lives of these traveling performers.

The Bunraku Stage

The Musician's Stage (Yuka)

The yuka is a special stage where the gidayu-bushi music is performed. It sticks out into the audience area on the front right side. On this stage, there is a spinning platform. This is where the chanter and the shamisen player appear. When they finish, the platform spins again. This takes them backstage and brings the next performers onto the stage.

Partitions (Tesuri) and the Pit (Funazoko)

Between the front and back of the stage, there are three areas called "railings" (tesuri). The area behind the second railing is often called the pit. This is where the puppeteers stand. They stand here to make the puppets move in a lifelike way.

Small Curtain (Komaku) and Screened Rooms (Misuuchi)

From the audience's view, the right side of the stage is called the kamite (stage left). The left side is called the shimote (stage right). The puppets appear and leave the stage through small black curtains. Above these small curtains are screened-off rooms. They have special bamboo blinds so the audience cannot see inside.

Large Curtain (Joshiki-maku)

The joshiki-maku is a large curtain that hangs low from a ledge called the san-n-tesuri. It separates the audience area from the main stage. In the past, puppeteers stood behind this curtain. They held their puppets above the curtain so the audience could not see them. However, later on, the dezukai style of performance became popular. In this style, the puppeteers are seen on stage with the puppets, so the large curtain is not used to hide them.

See also

- Hachioji Kuruma Ningyo

- Shigeru Nanba, a Japanese painter who includes bunraku puppets in his art.

|

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |