Esperanto facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Esperanto |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

The Esperanto flag

|

||||

| Created by | L. L. Zamenhof | |||

| Date | 26th July 1887 | |||

| Setting and usage | International auxiliary language | |||

| Users | (Native: 200 to 1,000 cited 1996) L2 users: 10,000 to 2,000,000 |

|||

| Purpose | ||||

| Early forms: |

Proto-Esperanto

|

|||

| Writing system | Latin (Esperanto alphabet) | |||

| Sources | Vocabulary from Romance and Germanic languages; phonology from Slavic languages | |||

| Official status | ||||

| Regulated by | Akademio de Esperanto | |||

| Linguist List | epo | |||

| Linguasphere | 51-AAB-da | |||

|

||||

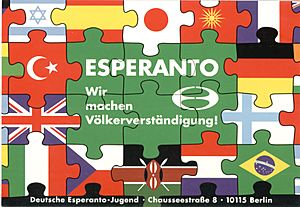

Esperanto is a constructed language that was created to make talking between people from different countries easier. It was also designed to be simple to learn. Ludovic Lazarus Zamenhof, a Polish eye doctor, made this language in the 19th century.

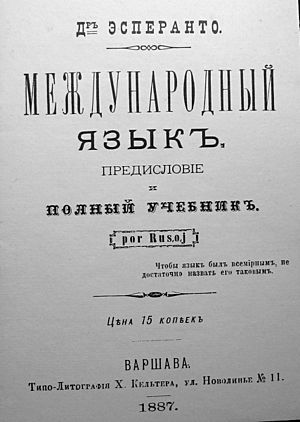

At first, Zamenhof called his language La Internacia Lingvo. This means "The International Language" in Esperanto. But soon, people started calling it Esperanto. This name means "a hopeful person." It came from Doktoro Esperanto ("Doctor Hopeful"), which was Zamenhof's pen name in his first book about the language.

People speak Esperanto in many countries and on all major continents. We don't know exactly how many people speak it. Most sources say there are between a few hundred thousand and two million Esperanto speakers. A small number of people, maybe around 2,000, grew up speaking Esperanto as their first language. This makes Esperanto the most used constructed language in the world.

Someone who speaks or supports Esperanto is often called an "Esperantist."

Contents

The Story of Esperanto

How Esperanto Began

Ludovic Lazarus Zamenhof created Esperanto. He grew up in Białystok, a town that is now in Poland. Back then, it was part of the Russian Empire. Many different languages were spoken in Białystok. Zamenhof saw arguments between the different ethnic groups living there, like Russians, Poles, Germans, and Jews.

He believed that these problems happened because people didn't have a common language. So, he decided to create a language that everyone could share. He wanted it to be different from national languages. It needed to be fair to all cultures and easy to learn. He hoped people would learn Esperanto along with their own languages. They could then use it to talk with people who spoke other native languages.

Zamenhof's First Ideas

Zamenhof first thought about bringing Latin back into use. He learned Latin in school. But he soon realized it was too hard for everyday use. He also studied English. From English, he learned that languages don't always need to change verbs based on who is speaking or how many people.

One day, he saw two Russian words: швейцарская (reception) and кондитерская (confectionery). Both words had the same ending. This gave him an idea. He thought that using regular prefixes and suffixes could reduce the number of word roots needed for communication. Zamenhof wanted the root words to be neutral. So, he chose words from Romance and Germanic languages. These languages were taught in many schools worldwide at that time.

Creating the Final Version

Zamenhof finished his first language project, Lingwe uniwersala (Universal Language), in 1878. But his father, who was a language teacher, thought his son's work was not realistic. He destroyed the original papers.

Between 1879 and 1885, Zamenhof studied medicine in Moscow and Warsaw. During this time, he worked on his international language again. In 1887, he published his first textbook, Международный языкъ ("The International Language"). Because of Zamenhof's pseudonym Doktoro Esperanto ("Doctor who hopes"), many people started calling the language "Esperanto."

Early Changes and Growth

Zamenhof received many excited letters. People sent him ideas for changes to the language. He wrote down all these suggestions. He published them in a magazine called La Esperantisto. In this magazine, Esperanto speakers could vote on the changes. They decided not to accept them.

The magazine had many readers in Russia. But it was banned there because of an article about Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy. After that, the magazine stopped being published. A new magazine, Lingvo Internacia, took its place.

The Esperanto Community Grows

In the early years, people mostly used Esperanto in writing. But in 1905, the first World Congress of Esperanto was held in Boulogne-sur-Mer, France. This was the first important time Esperanto was used for international talking. Because this congress was so successful, it has been held every year since then, except during the World Wars.

In 1912, Zamenhof stepped down from his leadership role in the movement. This happened at the eighth World Congress of Esperanto in Kraków, Poland. The tenth World Congress of Esperanto, planned for Paris, France, did not happen because World War I started. Nearly 4,000 people had signed up for it.

Esperanto During the World Wars

During World War I, the World Esperanto Association had its main office in Switzerland. Switzerland was neutral in the war. A group of volunteers, led by Hector Hodler and supported by Romain Rolland, helped send letters between countries that were at war. They did this through Switzerland. In total, they helped with 200,000 cases.

After World War I, there was new hope for Esperanto. People wanted peace, and Esperanto and its community grew. The first World Congress after the war took place in Hague, Netherlands, in 1920. An Esperanto Museum opened in Vienna, Austria, in 1929. Today, it is part of the Austrian National Library.

World War II stopped this progress. Many Esperantists were sent to fight, and many others died in concentration camps. Nazis targeted Esperantists because they thought Esperanto was part of a global Jewish plan. Esperantists were also treated badly in the Soviet Union during Stalin's time.

After the Wars

After World War II, many people supported Esperanto. Eighty million people signed a petition asking for Esperanto to be used in the United Nations.

Every year, large Esperanto meetings are held. These include the World Congress of Esperanto, the International Youth Congress of Esperanto, and the SAT-Congress.

In 1990, the Holy See (the Pope's office) allowed the use of Esperanto in Masses without special permission. Esperanto is the only constructed language that has this permission from the Roman Catholic Church.

Esperanto has many websites, blogs, podcasts, and videos. People use it on social media and in online chats. They also use it for private talks through e-mail and instant messaging. Some computer programs, especially free and open source ones, have an Esperanto version. The online radio station Muzaiko has been broadcasting in Esperanto 24 hours a day since 2011.

What Esperanto Hopes to Achieve

Zamenhof wanted to create an easy language to help people from different countries understand each other better. He wanted Esperanto to be a universal second language. This means he didn't want it to replace national languages. Instead, he hoped most people around the world would learn and speak Esperanto. Many early Esperantists shared this goal.

The General Assembly of UNESCO officially recognized Esperanto in 1954. Since then, the World Esperanto Association has worked closely with UNESCO. However, Esperanto was never chosen by the United Nations or other big international groups. It has not become a widely accepted second language.

Some Esperanto speakers like the language for reasons other than its use as a universal second language. They enjoy the Esperanto community and its culture. For these people, developing the Esperanto culture is an important goal.

People who care more about Esperanto's current value than its potential for universal use are sometimes called raŭmistoj in Esperanto. Their ideas are called raŭmismo, or "Raumism." These names come from the town of Rauma, in Finland. The International Youth Congress of Esperanto met there in 1980. They made a big statement saying that making Esperanto a universal second language was not their main goal.

People whose goals for Esperanto are more like Zamenhof's are sometimes called finvenkistoj in Esperanto. This name comes from fina venko, an Esperanto phrase meaning "final victory." It refers to a future where almost everyone on Earth speaks Esperanto as a second language.

The Prague Manifesto (1996) explains the ideas of the regular people in the Esperanto movement. It also states the goals of its main organization, the World Esperanto Association (UEA).

The German town of Herzberg am Harz has been called die Esperanto-Stadt/la Esperanto-urbo ("the Esperanto town") since July 12, 2006. They teach the language in elementary schools. They also hold cultural and educational events using Esperanto with their Polish twin town Góra.

Esperanto is the only constructed language that the Roman Catholic Church recognizes for religious services. They allow Masses to be held in the language. Vatican Radio also broadcasts in Esperanto every week.

Esperanto Culture

Many people use Esperanto to talk with other Esperantists in different countries. They communicate by mail, email, blogs, or chat rooms. Some even travel to other countries to meet and speak Esperanto with fellow speakers.

Meetings and Events

Esperantists hold annual meetings. The biggest one is the Universala Kongreso de Esperanto ("World Congress of Esperanto"). It takes place in a different country each year. Recently, about 2,000 people from over 60 countries have attended. For young people, there is the Internacia Junulara Kongreso ("International Youth Congress of Esperanto").

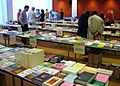

Many cultural activities happen during Esperanto meetings. These include concerts by Esperanto musicians, dramas, discos, and presentations about the host country's culture. There are also lectures, language courses, and more. At the meeting locations, you can find a pub, a tearoom, and a bookstore with Esperanto-speaking staff. The number of activities depends on the size and theme of the meeting.

Books and Stories

There are many books and magazines written in Esperanto. A lot of literature has been translated into Esperanto from other languages. This includes famous works like the Bible (first translated in 1926) and plays by Shakespeare. Less famous works have also been translated into Esperanto, and some of these don't have English translations.

Important Esperanto writers include Trevor Steele (Australia), István Nemere (Hungary), and Mao Zifu (China). William Auld was a British poet who wrote in Esperanto. He was even suggested for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Music in Esperanto

Esperanto music comes in many different genres. You can find folk songs, rock music, cabaret, songs for solo singers, choirs, and even opera.

Some active Esperanto musicians are the Swedish group La Perdita Generacio, Occitan singer JoMo, the Finnish group Dolchamar, Brazilian group Supernova, Frisian group Kajto, and Polish singer-songwriter Georgo Handzlik. Some popular artists like Elvis Costello and Michael Jackson have recorded songs in Esperanto. Others have made songs inspired by the language or used it in their promotions.

An album called "Esperanto" was released by Warner Bros. in Spain in November 1996. All its songs were in Esperanto, and some reached high positions on the Spanish music charts. In 1999, the German hip-hop group Freundeskreis became famous with their song "Esperanto." Classical pieces for orchestra and choir with Esperanto lyrics include La Koro Sutro by Lou Harrison and The First Symphony by David Gaines (both from the USA). In Toulouse, France, there is Vinilkosmo, a company that produces Esperanto music. The main online Esperanto songbook, KantarViki, had 3,000 songs by May 2013.

Theatre and Film

Plays by writers like Carlo Goldoni, Eugène Ionesco, and William Shakespeare are also performed in Esperanto. Filmmakers sometimes use Esperanto in the background of movies. For example, it appears in The Great Dictator by Charlie Chaplin, the action film Blade: Trinity, and the sci-fi TV series Red Dwarf.

Full-length movies in Esperanto are not very common. However, there are about 15 feature films that have Esperanto themes. The 1966 film Incubus is special because all its dialogue is in Esperanto. Today, some people translate subtitles of different films into Esperanto. The website Verda Filmejo collects these subtitles.

Radio and Television

Radio stations in Brazil, China, Cuba, and Vatican broadcast regular programs in Esperanto. Other radio programs and podcasts are available online. The internet radio station Muzaiko has been broadcasting Esperanto programs 24 hours a day since July 2011. Between 2005 and 2006, there was also a project for an international television channel called "Internacia Televido" in Esperanto. Esperanto TV has been broadcasting online from Sydney, Australia, since April 5, 2014.

Esperanto on the Internet

On the Internet, there are many online discussions in Esperanto about different topics. There are many websites, blogs, podcasts, videos, and online TV and radio stations (as mentioned above). Google Translate has supported translations from and into Esperanto since February 22, 2012. It was their 64th language.

Besides websites and blogs by Esperantists and Esperanto groups, there is also Esperanto Wikipedia. Other projects by the Wikimedia Foundation also have an Esperanto version or use Esperanto. These include Wikibooks, Wikisource, Wikinews, Wikimedia Commons, and Wikidata. People can also use Esperanto versions of social networks like Facebook and Diaspora, and other websites.

Several computer programs also have an Esperanto version. These include the web browser Firefox and the office suite (a set of programs for office work) LibreOffice.

How the Language Works

Esperanto uses grammar and words from many natural languages. These include Latin, Russian, and French. The smallest parts of a word that have meaning in Esperanto (called morphemes) do not change. People can combine them to make many different words.

Esperanto has some things in common with isolating languages like Chinese. These languages use word order to change the meaning of a sentence. But the inner structure of Esperanto words is like agglutinative languages such as Turkish, Swahili, and Japanese. These languages use affixes (small parts added to words) to change meaning.

The Esperanto Alphabet

The Esperanto alphabet has 28 letters. Here they are:

| Big letter: | A | B | C | Ĉ | D | E | F | G | Ĝ | H | Ĥ | I | J | Ĵ | K | L | M | N | O | P | R | S | Ŝ | T | U | Ŭ | V | Z |

| Small letter: | a | b | c | ĉ | d | e | f | g | ĝ | h | ĥ | i | j | ĵ | k | l | m | n | o | p | r | s | ŝ | t | u | ŭ | v | z |

| IPA: | a | b | t͡s | t͡ʃ | d | e | f | g | d͡ʒ | h | x | i | j | ʒ | k | l | m | n | o | p | r | s | ʃ | t | u | u̯ | v | z |

Here's how to say some of the letters:

- A in Esperanto sounds like a in father.

- C is like ts in lets.

- Ĉ is like ch in chocolate.

- Ĝ is like j and dg in judge.

- Ĥ makes a sound that vibrates the throat. This sound is not in English. It's often written as kh or ch in foreign names.

- J is like y in you.

- Ĵ is like s in pleasure.

- R is like r in road but is rolled (like in Spanish or Italian).

- Ŝ is like sh in short.

- Ŭ is like w in cow.

There are no Q, W, X, or Y in the Esperanto alphabet. The letters ĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ, ŭ have special marks called diacritics. Because the letter x is not used in Esperanto, these letters can also be written as cx, gx, hx, jx, sx, ux. This way of writing is called the "x-sistemo" ("x-system").

Zamenhof also created another way to write these letters using the letter h as a helper (except for u). So, you can write them as ch, gh, hh, jh, sh and u. This is called the "h-sistemo" ("h-system").

In the past, it was hard to type Esperanto letters with diacritics on computers. People had to use the h-system or x-system. But today's programs can use Unicode, so this problem is gone. However, some people still use these systems when they don't have Esperanto letters on their keyboards.

Examples of Esperanto Words

Esperanto words come from many different languages:

- From Romance languages (like Latin, French, Italian):

- abio (fir), sed (but), okulo (eye), akvo (water)

- dimanĉo (Sunday), frapi (to knock), ĉevalo (horse)

- facila (easy), fero (iron), tra (through), verda (green)

- From Germanic languages (like German, English):

- baldaŭ (soon), bedaŭri (to regret), jaro (year), nur (only)

- birdo (bird), ŝarko (shark), jes (yes)

- fiŝo (fish), fremda (foreign), ofta (frequent)

- From Slavic languages (like Polish, Russian, Czech):

- ĉu (word for yes/no questions)

- barakti (to fight), vosto (tail)

- ne (no), roboto (robot), ĉerpi (to pump)

- From other Indo-European languages (like Greek, Lithuanian, Sanskrit):

- hepato (liver), kaj (and), biologio (biology)

- du (two), tuj (at once)

- From Finno-Ugric languages (like Finnish, Hungarian):

- saŭno (sauna)

- From Semitic languages (like Hebrew, Arabic):

- kabalo (Kabbalah)

- From other languages (like Japanese, Chinese, Hawaiian):

Esperanto Grammar

Grammar means the rules of a language. Esperanto's grammar is meant to be simple. The rules in Esperanto never change. You can always use them in the same way.

Articles

Esperanto has only one definite article: la. This is like "the" in English. It has no indefinite article, like "a" or "an" in English. You use la when you talk about things you have already mentioned.

Nouns and Adjectives

| Nominative | Accusative | |

|---|---|---|

| Singular | -o | -on |

| Plural | -oj | -ojn |

Nouns in Esperanto end with -o. For example, patro means father. To make a noun plural, you add -j. So, patroj means fathers.

| Nominative | Accusative | |

|---|---|---|

| Singular | -a | -an |

| Plural | -aj | -ajn |

Adjectives end with -a. Adverbs end with -e. For example, granda means big. Bona means good, and bone means well.

The -n ending shows the direct object (the Accusative case) for nouns and adjectives. For example:

- Mi vidas vin. - I see you.

- Li amas ŝin. - He loves her.

- Ili havas belan domon. - They have a nice house.

When comparing adjectives and adverbs, you use the words pli (more) and plej (most). For example:

- pli granda - bigger

- plej granda - biggest

- pli rapide - faster

- plej rapide - fastest

Pronouns

| Singular | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| First person | mi (I) | ni (we) | |

| Second person | vi (you) | ||

| Third person |

Masculine | li (he) | ili (they) |

| Feminine | ŝi (she) | ||

| Neuter | ĝi (it) | ||

| Uncertain | oni („someone“) | ||

| Reflexive | si (self) | ||

- Personal pronouns are: mi (I), vi (you), li (he), ŝi (she), ĝi (it), ni (we), ili (they), oni (someone/they), si (self). The pronoun oni is used when the subject is not specific.

- Possessive pronouns are made by adding -a to a personal pronoun. For example: mia (my), via (your), lia (his), ŝia (her), ĝia (its), nia (our), ilia (their). Possessive pronouns are used like adjectives.

- The Accusative case (the -n ending) is also used for pronouns. For example: min (me), vin (you), lin (him), ŝin (her), ĝin (it), nin (us), ilin (them).

To say someone's age in Esperanto, you say:

- Lia aĝo estas dudek = He is twenty years old. (Word for word: His age is twenty.)

Verbs

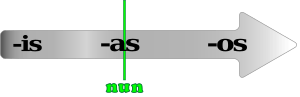

-is – past tense

-as – present tense

-os – future tense

| Indicative mood | Active participle | Passive participle | Infinitive | Jussive mood | Conditional mood | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Past tense | -is | -int- | -it- | -i | -u | -us |

| Present tense | -as | -ant- | -at- | |||

| Future tense | -os | -ont- | -ot- |

Verbs end with -as in the present tense. In English, we say "I am," "you are," "he is." But in Esperanto, there is only one word for "am," "are," "is" – estas. Similarly, kuras can mean "run" or "runs."

Infinitives (the "to do" form of a verb) end with -i. For example, esti means "to be," and povi means "to be able to." It is easy to make the past tense – always add the -is ending. To make the future tense, add -os. For example:

- kuri - to run

- mi kuras - I run

- vi kuras - you run

- li kuris - he ran

- ĝi kuros - it will run

Many words can be made opposite by adding mal- at the beginning.

- bona = good. malbona = bad.

- bone = well. malbone = poorly.

- granda = big. malgranda = small.

- peza = heavy. malpeza = light.

Here are some example sentences that show the rules:

- Mi povas kuri rapide. = I can run fast.

- Vi ne povas kuri rapide. = You cannot run fast.

- Mi estas knabo. = I am a boy.

- Mi estas malbona Esperantisto. = I am a bad Esperantist.

Asking Yes/No Questions

To ask a yes-or-no question, add Ĉu at the beginning of the sentence. For example:

- Ĉu vi parolas Esperanton? = Do you speak Esperanto?

- Jes, mi parolas Esperanton tre bone. = Yes, I speak Esperanto very well.

- Ne, mi estas komencanto. = No, I am a beginner.

Unlike in English, you can only answer a yes/no question with jes (yes) or ne (no).

Numbers

The numbers in Esperanto are:

| 0 | nul |

| 1 | unu |

| 2 | du |

| 3 | tri |

| 4 | kvar |

| 5 | kvin |

| 6 | ses |

| 7 | sep |

| 8 | ok |

| 9 | naŭ |

| 10 | dek |

| 100 | cent |

| 1000 | mil |

Numbers like twenty-one (21) are made by combining their parts. For example:

- dek tri means thirteen (13).

- dudek tri means twenty-three (23).

- sescent okdek tri means six hundred eighty-three (683).

- mil naŭcent okdek tri means one thousand nine hundred eighty-three (1983).

Prefixes and Suffixes

Esperanto has over 20 special word parts that can change the meaning of another word. People put them before (prefixes) or after (suffixes) the main part of a word.

These parts can be combined to make very long words. For example, malmultekosta (cheap) or vendredviandmanĝmalpermeso (prohibition of eating meat on Friday).

Prefixes (Added at the Beginning)

- bo- – means "in-law". Patro means father, so bopatro means father-in-law.

- dis- – means "in all or many directions". Iri means to go, so disiri means to go in different directions.

- ek- – means "start" of something. Kuri means to run, so ekkuri means to start running.

- eks- – makes the word "former". Amiko means friend, so eksamiko means former friend.

- fi- – makes the word worse or ugly. Knabo means boy, so fiknabo means bad boy. Odoro means smell, so fiodoro means bad smell.

- ge- – changes the meaning to "both genders". Frato means brother, so gefratoj means brother(s) and sister(s).

- mal- – makes the word opposite. Bona means good, so malbona means bad.

- mis- – means "wrong". Kompreni means to understand, so miskompreni means to misunderstand.

- pra- – means "prehistoric", "very old", or "primitive". Homo means human, so prahomo means prehistoric human.

- re- – means again. Vidi means to see, so revidi means to see again.

Suffixes (Added at the End)

Suffixes are added after the main part of the word, but before the ending.

- -aĉ- – makes the word uglier or worse. Domo means house, so domaĉo means ugly house.

- -ad- – means doing something continuously. Fari means to do, so faradi means to do continuously.

- -aĵ- – means a thing. Bela means beautiful, so belaĵo means a beautiful thing. Trinki means to drink, so trinkaĵo means a drink (something for drinking).

- -an- – means member of something. Klubo means club, so klubano means a member of a club.

- -ar- – means many things of the same kind or a collection. Arbo means tree, so arbaro means forest (a collection of trees).

- -ĉj- – makes male diminutives (like a nickname). Patro means father, so paĉjo means daddy.

- -ebl-– means ability or possibility. Manĝi means to eat, so manĝebla means eatable.

- -ec- – means quality. Granda means big, so grandeco means size (the quality of being big).

- -eg- – makes the word bigger. Domo means house, so domego means big house.

- -ej- – means a place. Lerni means to learn, so lernejo means school (a place for learning).

- -em- – means tendency or inclination. Mensogi means to lie, so mensogema means with a tendency to lie.

- -end- – means something that must be done. Pagi means to pay, so pagenda means something that must be paid.

- -er- – means a small piece of a larger group. Neĝo means snow, so neĝero means snowflake.

- -estr- – means a chief of. Urbo means town, so urbestro means mayor (chief of a town).

- -et- – makes the word smaller. Domo means house, so dometo means small house.

- -id- – means the child of. Kato means cat, so katido means kitten.

- -il- – means instrument or tool. Ŝlosi means to lock, so ŝlosilo means key (an instrument for locking).

- -ind- – means worthiness. Ami means to love, so aminda means something worth loving.

- -in- – changes the gender of a word to female. Patro means father, so patrino means mother.

- -ing- – means a holder. Kandelo means candle, so kandelingo means candlestick (a holder for a candle).

- -ism- – means an ideology or movement. Nacio means nation, so naciismo means nationalism.

- -ist- – means somebody who does something (perhaps as a job). Baki means to bake, so bakisto means baker. Scienco means science, so sciencisto means scientist. Esperantisto means Esperanto speaker.

- -nj- – makes female diminutives. Patrino means mother, so panjo means mummy.

- -obl- – means times. Tri means three, so trioble means three times.

- -on- – makes fractions. Kvar means four (4), so kvarono means quarter (one fourth of something).

- -uj- – generally means a vessel or container. Salo means salt, so salujo means salt shaker (a vessel for salt).

- -ul- – means person of some quality. Juna means young, so junulo means young man.

- -um- is a special suffix used when no other existing suffix, prefix, or root can form a word.

Common Criticisms of Esperanto

Some criticisms of Esperanto are common for any constructed international language. For example, some people say a new language has little chance to replace today's international languages like English or French.

Other criticisms are specific to Esperanto itself. These include its special letters, the -n ending, and the sound of the language.

Some people say that using the diacritics (the letters ĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ, ŭ) makes the language less neutral. This is because these letters are not used in any other language in the basic Latin alphabet.

Critics also say that having the same ending for an adjective and a noun (like "bona lingvo", "bonaj lingvoj", "bonajn lingvojn") is not needed. English, for example, does not have this.

Another criticism is that most Esperanto words come from Indo-European languages. This makes the language less neutral for people who speak other language families.

One common criticism, from both non-Esperanto speakers and Esperantists, is that there is some language sexism in Esperanto. This is because some words have a male meaning by default. You have to add the -in- suffix to make them feminine. Examples are patro (father) and patrino (mother), or filo (son) and filino (daughter). Most Esperanto words, however, do not have a specific gender meaning. Some people have suggested a suffix -iĉ- for male meaning to make the basic word neutral. But this idea is not widely accepted by Esperantists.

Criticism of parts of Esperanto led to the creation of other constructed languages. These include Ido, Novial, Interlingua, Neoslavonic language, and Lojban. However, none of these languages have as many speakers as Esperanto.

Example of Esperanto Text

Here is a sentence from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Esperanto:

Normal way: [Ĉiuj homoj estas denaske liberaj kaj egalaj laŭ digno kaj rajtoj. Ili posedas racion kaj konsciencon, kaj devus konduti unu la alian en spirito de frateco.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)

Using the x-system: [Cxiuj homoj estas denaske liberaj kaj egalaj laux digno kaj rajtoj. Ili posedas racion kaj konsciencon, kaj devus konduti unu la alian en spirito de frateco.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)

Using the h-system: [Chiuj homoj estas denaske liberaj kaj egalaj lau digno kaj rajtoj. Ili posedas racion kaj konsciencon, kaj devus konduti unu la alian en spirito de frateco.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)

Simple English translation: All people are free and equal in dignity and rights. They are reasonable and moral, and should act kindly to each other.

Metaphorical Use of "Esperanto"

Sometimes, people use the word "Esperanto" in a metaphorical way. This means they don't use its literal meaning. They use it to say that something is, or is planned to be, international, neutral, or a mixture of things. For example, they might say the programming language Java is "independent on specific platform like Esperanto is independent on concrete nation." Or they might call the font Noto "the Esperanto of fonts."

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: Esperanto para niños

In Spanish: Esperanto para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |