George Antheil facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

George Antheil

|

|

|---|---|

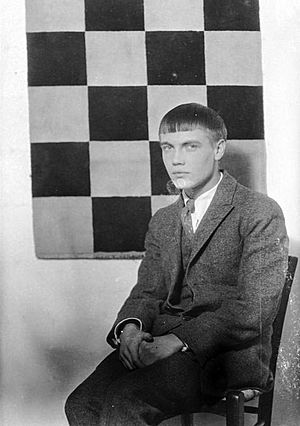

Detail from a portrait of Antheil, by American photographer Berenice Abbott, c. 1927

|

|

| Born | July 8, 1900 Trenton, New Jersey, U.S.

|

| Died | February 12, 1959 (aged 58) |

| Occupation | |

| Spouse(s) |

Boski Markus

(m. 1941) |

| Children | 1 |

| Signature | |

|

|

George Antheil (born July 8, 1900 – died February 12, 1959) was an American composer, pianist, writer, and inventor. He was known for his very modern music that explored the sounds of machines and industry in the early 1900s.

Antheil spent much of the 1920s in Europe. When he returned to the United States in the 1930s, he started writing music for movies and later for television. This made his music style change to be more traditional. George Antheil was a person with many different interests and talents. He was always trying new things. He wrote articles for magazines, an autobiography (a book about his own life), a mystery novel, and columns for newspapers and music magazines.

In 1941, Antheil and the famous actress Hedy Lamarr created a special radio system. This system helped guide Allied torpedoes. It used a secret code to quickly change radio frequencies, making it hard for enemies to block the signal. This idea is now called frequency hopping. It is used a lot today in things like cell phones and Wi-Fi. Because of this important work, they were added to the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2014.

Contents

Early Life and Musical Beginnings

George Johann Carl Antheil grew up in Trenton, New Jersey. His family had come from Germany. His father owned a shoe store. George went to public schools in Trenton. He learned to speak two languages and started writing music, stories, and poems when he was very young. He never officially finished high school or college. He left Trenton Central High School in 1918.

In his autobiography, The Bad Boy of Music (1945), Antheil wrote that he was "so crazy about music." His mother even sent him to the countryside where there were no pianos. But George still found a way to get a piano delivered! His book also made his early life sound more exciting, saying he grew up near a noisy machine shop and a prison. George's younger brother, Henry W. Antheil Jr., was a diplomatic courier. He died on June 14, 1940, when his plane was shot down over the Baltic Sea.

Antheil began playing the piano at age six. In 1916, he often traveled to Philadelphia to study with Constantine von Sternberg. Sternberg had been a student of the famous composer Franz Liszt. From Sternberg, Antheil learned how to compose music in the European style. His trips to the city also showed him new art ideas, like Dadaism. In 1919, he started working with Ernest Bloch in New York. Bloch first thought Antheil's music was "empty." But he was impressed by Antheil's energy and helped him financially.

In New York, Antheil met important artists and musicians. These included Leo Ornstein, Paul Rosenfeld, John Marin, Alfred Stieglitz, and Margaret Caroline Anderson. Anderson was the editor of The Little Review.

When he was 19, Antheil was invited to spend a weekend with Margaret Anderson and her friends. He ended up staying for six months! This group, which included Georgette Leblanc, became very important to Antheil's career. Anderson described Antheil as short with an unusual nose. She said he played "a compelling mechanical music." He used the piano like a drum, making it sound like a xylophone or a cymbal. During this time, Antheil worked on songs, a piano concerto, and a piece called "The Mechanisms."

Around this time, von Sternberg introduced Antheil to Mary Louise Curtis Bok. She later started the Curtis Institute of Music. Bok gave Antheil $150 a month and arranged for him to study at the Philadelphia Settlement Music School. Even though she didn't always like his behavior or his music, she kept helping him for 20 years. Her support allowed Antheil to be independent in his work.

Antheil kept studying piano and modern music by composers like Igor Stravinsky. In 1921, he wrote his first piece inspired by technology, the piano solo Second Sonata, "The Airplane". Other similar works included Sonata Sauvage (1922–23) and Third Sonata, "Death of Machines" (1923). He also worked on his first symphony. The famous conductor Leopold Stokowski was going to perform it. But before that could happen, Antheil left for Europe to build his career. This might have made it harder for him to succeed in America at first.

Life in Berlin and Paris

On May 30, 1922, at age 21, Antheil sailed to Europe. He wanted to become known as a "new ultra-modern pianist composer." He started his European career with a concert at Wigmore Hall in London. He played music by Claude Debussy and Stravinsky, along with his own pieces.

He spent a year in Berlin, planning to work with Artur Schnabel. He also gave concerts in Budapest, Vienna, and at the Donaueschingen Festival. He became famous, but often had to pay for the concerts himself. His financial situation got worse when Mrs. Bok cut his monthly money in half. However, she often helped pay for specific parts of his concerts. He met Boski Markus, a Hungarian woman who became his partner. They married in 1925.

In 1922, Antheil met his idol, Stravinsky, in Berlin. They became good friends, and Stravinsky encouraged Antheil to move to Paris. Stravinsky even arranged a concert to help Antheil start his career in Paris. But Antheil didn't show up, choosing to travel to Poland with Markus instead. The Antheils finally arrived in Paris in June 1923. They saw the first performance of Stravinsky's ballet Les Noces. But their friendship didn't last. Stravinsky felt Antheil had boasted too much about their friendship. This upset Antheil greatly. They didn't become friends again until 1941.

Even with a rocky start, Antheil loved Paris. It was a hub of new music and art. He called it a "green tender morning" compared to Berlin's "black night."

The couple lived in an apartment above Sylvia Beach's bookshop, Shakespeare and Company. Beach described Antheil as "a fellow with bangs, a squished nose and a big mouth with a grin in it. A regular American high school boy." She was very supportive. She introduced Antheil to her friends and customers. These included Erik Satie, Ezra Pound, James Joyce, Virgil Thomson, and Ernest Hemingway. Joyce and Pound soon talked about working with Antheil on an opera.

Ezra Pound became a big supporter of Antheil. He compared him to Stravinsky and James Cagney. Pound said Antheil was breaking music down to its "musical atom." Pound introduced Antheil to Jean Cocteau, who helped Antheil get into Paris's music gatherings. Pound also asked Antheil to write three violin sonatas for his girlfriend, Olga Rudge. In 1924, Pound published a book called Antheil and the Treatise on Harmony. This book was meant to help Antheil's fame, but it might have done more harm than good. Antheil later tried to distance himself from it. Natalie Barney helped produce some of Antheil's early works, including the First String Quartet in 1925.

Antheil was asked to perform in Paris at the opening of the Ballets suédois. He played several new pieces, like the "Airplane Sonata" and "Mechanism." During his performance, a riot started! Antheil was thrilled. He said, "People were fighting in the aisles, yelling, clapping, hooting! Pandemonium!" Police came, and many people were arrested. This riot was even filmed for a movie called L'Inhumaine. Famous people like Erik Satie, Darius Milhaud, Man Ray, Pablo Picasso, and Jean Cocteau were in the audience. Antheil was happy when Satie and Milhaud praised his music.

His first performances often got mixed reactions. His playing was loud and forceful. Critics said he hit the piano instead of playing it. He often hurt himself doing this. To show his "bad boy" image, Antheil would sometimes pull a revolver from his jacket and place it on the piano.

Ballet Mécanique and European Works

Antheil's most famous piece is Ballet Mécanique. This "ballet" was originally meant to go with a film by Fernand Léger and Dudley Murphy. However, the film was only about 19 minutes long, while Antheil's music was twice as long. So, the first performances in 1925 and 1926 did not include the film.

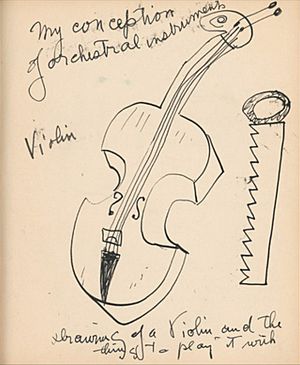

Antheil described his "first big work" as being for "countless numbers of player pianos. All percussive. Like machines. All efficiency. No LOVE. Written without sympathy. Written cold as an army operates." His first idea was for 16 specially synchronized player pianos, two grand pianos, electronic bells, xylophones, drums, a siren, and three airplane propellers. But it was too hard to make them all work together. So, he rewrote it for one player piano and many human pianists. The piece had music and silent parts, with the loud sound of airplane propellers. Antheil called it "by far my most radical work... It is the rhythm of machinery, presented as beautifully as an artist knows how." The film and Antheil's music were finally performed together in New York in 1935.

Antheil worked hard to promote this piece. He even pretended to disappear while visiting Africa to get media attention for a concert. The official Paris premiere in June 1926 caused a stir. Some people in the audience were very angry, but others strongly supported the work. The concert ended with a riot in the streets!

On April 10, 1927, Antheil rented Carnegie Hall in New York. He put on a concert of only his works. This included the American debut of Ballet Mécanique in a smaller version. He had big backdrops of skyscrapers and machines. He also hired an African American orchestra to play his A Jazz Symphony. The concert started well. But when the wind machine was turned on, "all hell... broke loose." Audience members held onto their hats, and one even waved a handkerchief on a cane as a sign of surrender. The siren, which hadn't been tested, failed to sound on time. It only went off after the performance ended, as people were leaving. American critics were not kind. They called the concert "a bitter disappointment" and said Ballet Mécanique was "boring." Antheil's hoped-for riots didn't happen. The failure of Ballet Mécanique affected him deeply. He never fully got his reputation back during his lifetime. However, other famous composers like Arthur Honegger and Sergei Prokofiev were influenced by his interest in mechanical sounds. In 1954, Antheil made a new version of the work for percussion, four pianos, and a recording of an airplane motor.

In the late 1920s, Antheil moved to Germany. He worked as an assistant music director at a theater in Berlin. He wrote music for ballets and plays. In 1930, his first opera, Transatlantic, premiered. This opera was about American politics, gangsters, and a restaurant. It was a success at the Frankfurt Opera. In 1933, the Nazi party came to power. They did not like Antheil's modern music. So, during the Great Depression, he returned to the US and settled in New York City.

He eagerly rejoined American life. He organized concerts, worked with composers like Aaron Copland, and wrote music for piano, ballet, and films. He also wrote an opera called Helen Retires about Helen of Troy, but it was not successful. His music had become less extreme and more traditional, with some romantic elements.

Hollywood Career

In 1936, Antheil went to Hollywood. He became a popular film composer. He wrote over 30 scores for directors like Cecil B. DeMille and Nicholas Ray. These included The Scoundrel (1935) and The Plainsman (1936). Antheil and his wife had their only child, a son named Peter, in 1937. Antheil felt that the film industry was not open to modern music. He complained that most movie music was "unmitigated tripe" (meaning terrible). He relied more on independent producers like Ben Hecht for work. He scored films like Angels Over Broadway (1940) and Specter of the Rose (1946). He also wrote music for the independent films Dementia (1955) and In a Lonely Place (1950), which starred Humphrey Bogart. Antheil believed his music could save a weak film. He once said, "If I say so myself, I've saved a couple of sure flops."

Besides movie scores, he continued to compose other music, including ballets and six symphonies. His later works were more romantic and influenced by composers like Prokofiev and Shostakovich, as well as American jazz. Works like Serenade No. 1 and Piano Sonata No. 4, written in 1948, showed his desire to create music that used melody and traditional forms. His 1953 opera Volpone premiered in New York to mixed reviews. A visit to Spain in the 1950s influenced some of his last works, including the film score for The Pride and the Passion (1957). He also wrote the theme music for the CBS Television newsreel series The Twentieth Century (1957–1966), narrated by Walter Cronkite.

Other Interests and Inventions

Beyond music, Antheil had many other interests. In 1930, using the name Stacey Bishop, he wrote a mystery novel called Death in the Dark. One character in the book was based on Ezra Pound. From 1936 to 1940, he was a film music reporter and critic for Modern Music magazine. He wrote lively and thoughtful columns. However, he was disappointed with Hollywood. He wrote that after trying new composers, Hollywood went back to making "easy and sure-fire scores."

Before World War II, he was part of the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League. He helped put on exhibits of artworks that were banned in Nazi Germany. He also published a book of war predictions called The Shape of the War to Come.

In 1945, he published his autobiography, Bad Boy of Music, which became a bestseller.

Antheil also wrote a newspaper column that gave advice on relationships. He wrote regular columns for magazines like Esquire and Coronet.

Frequency-Hopping Invention

Antheil's wide range of interests led him to meet the actress Hedy Lamarr. During World War II, Lamarr realized that radio-controlled torpedoes could be easily stopped by enemies. They could block the signal by sending interference on the same frequency.

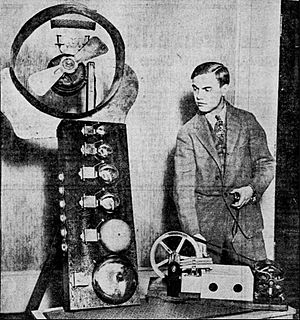

Antheil and Lamarr came up with an idea to solve this problem. They thought of using "frequency hopping." This meant the signal between the control center and the torpedo would quickly jump between 88 different radio frequencies. The specific order of these frequency changes would be known only by the controlling ship and the torpedo. This made the signal secret and very hard for the enemy to block. Antheil planned to use a player piano roll to control the sequence of frequency changes. He had used a similar mechanism for his Ballet Mécanique.

On August 11, 1942, Antheil and "Hedy Kiesler Markey" (Lamarr's married name) were granted U.S. Patent 2,292,387 for their invention. This early version of frequency hopping was very clever. However, the U.S. Navy did not use it at the time.

The idea was not put into use in the US until 1962. It was used by U.S. military ships during a blockade of Cuba, after the patent had expired. Because of this delay, the patent was not well known until 1997. That year, the Electronic Frontier Foundation gave Lamarr an award for her contributions. In 1998, a company bought a share of the expired patent from Lamarr. Antheil and Lamarr's frequency-hopping idea shares some concepts with modern wireless technology. This includes Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, and some cordless phones.

Later Life and Legacy

George Antheil died from a heart attack in Manhattan, New York City. He had three talented students: Henry Brant, Benjamin Lees, and Ruth White. He is buried in Riverview Cemetery in Trenton, New Jersey.

In Literature

"Antheil's my man." Mrs. McKisco turned challengingly to Rosemary, "Antheil and Joyce. I don't suppose you ever hear much about those sort of people in Hollywood, but my husband wrote the first criticism of Ulysses that ever appeared in America." (F. Scott Fitzgerald, Tender Is the Night)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: George Antheil para niños

In Spanish: George Antheil para niños

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |