Alfred Stieglitz facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

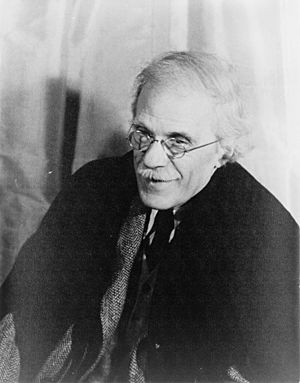

Alfred Stieglitz

|

|

|---|---|

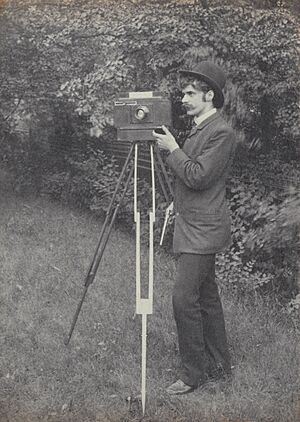

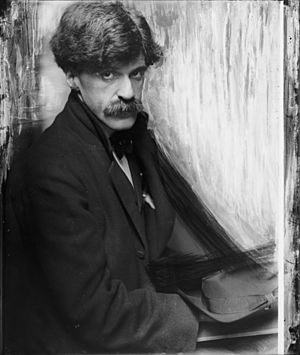

Stieglitz in 1902 by Gertrude Käsebier

|

|

| Born | January 1, 1864 Hoboken, New Jersey, U.S.

|

| Died | July 13, 1946 (aged 82) New York City, U.S.

|

| Known for | Photography |

| Spouse(s) | |

Alfred Stieglitz (January 1, 1864 – July 13, 1946) was an American photographer. He was also a big supporter of modern art. Over his 50-year career, he helped make photography accepted as a true art form. Besides his own photos, Stieglitz was famous for the art galleries he ran in New York City. There, he showed many new and exciting European artists to the U.S. He was married to the famous painter Georgia O'Keeffe.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Alfred Stieglitz was born in Hoboken, New Jersey. He was the first son of Edward and Hedwig Stieglitz, who were German immigrants. His father was a soldier in the Union Army (the army of the northern states during the American Civil War). He also worked as a wool merchant. Alfred had five brothers and sisters. He often wished he had a close friend like his twin brothers.

In 1871, Stieglitz went to the Charlier Institute, a Christian school in New York. The next year, his family started spending summers at Lake George. This was in the Adirondack Mountains. This became a family tradition that continued when Alfred grew up.

To get into the City College of New York, Stieglitz went to a public high school for a year. But he felt the teaching was not good enough. In 1881, his father sold his company. The family then moved to Europe for several years. This was so the children could get a better education. Alfred Stieglitz went to a school called the Real Gymnasium in Karlsruhe, Germany. The next year, he studied mechanical engineering at the Technische Hochschule in Berlin.

He also took a chemistry class taught by Hermann Wilhelm Vogel. Vogel was a scientist who worked on how to develop photographs. In Vogel, Stieglitz found both the challenge he needed and a way to explore his artistic interests.

Discovering Photography

In 1884, Stieglitz's parents went back to America. But 20-year-old Stieglitz stayed in Germany. He collected books about photography and photographers. He bought his first camera, a large 8 × 10 plate film camera. This camera used glass plates coated with chemicals to capture images. He traveled through the Netherlands, Italy, and Germany. He took pictures of landscapes and workers. He later wrote that photography "fascinated me, first as a toy, then as a passion, then as an obsession."

By studying on his own, he began to see photography as an art form. In 1887, he wrote his first article. It was called "A Word or Two about Amateur Photography in Germany." It was for a new magazine called The Amateur Photographer. He then wrote more articles about the technical and artistic sides of photography. These were for magazines in England and Germany.

He won first place for his photo, The Last Joke, Bellagio, in 1887. This was from Amateur Photographer. The next year, he won both first and second prizes in the same contest. His reputation grew as German and British photo magazines published his work.

In 1890, his sister Flora died while giving birth. Stieglitz then returned to New York.

Career Highlights

New York and the Camera Club (1891–1901)

Stieglitz saw himself as an artist. He did not want to sell his photographs. His father bought him a small photography business. This was so he could make a living doing what he loved. The company, Photochrome Engraving Company, rarely made money. This was because Stieglitz demanded very high quality and paid his workers well. He often wrote for The American Amateur Photographer magazine. He won awards for his photos at exhibitions. These included shows by the Boston Camera Club and other groups.

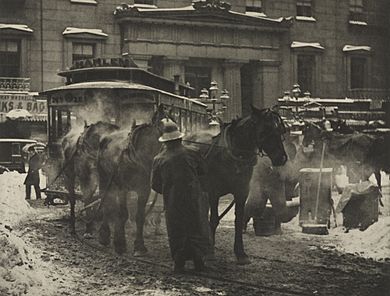

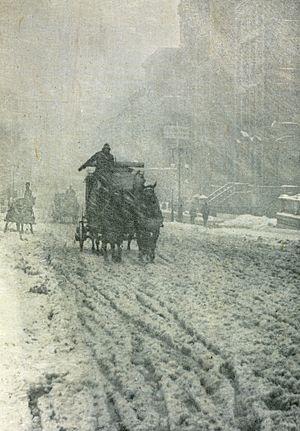

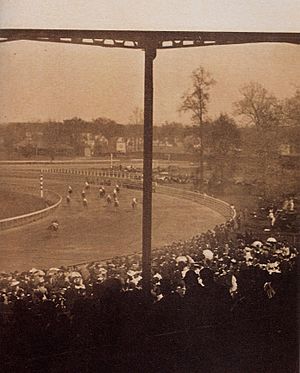

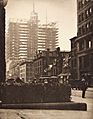

In late 1892, Stieglitz bought his first small, hand-held camera. It was a Folmer and Schwing 4×5 plate film camera. He used it to take two of his most famous pictures: Winter, Fifth Avenue and The Terminal. Before this, he used a large camera that needed a tripod.

Stieglitz became known for his photography and his articles. These articles explained how photography was an art form. In the spring of 1893, he became a co-editor of The American Amateur Photographer. He refused a salary because his company was printing the magazine's photogravures (a way of printing photos using etched plates). He wrote most of the articles and reviews. He was known for his technical and critical ideas.

On November 16, 1893, Stieglitz, then 29, married Emmeline Obermeyer, who was 20. She was the sister of a close friend. Stieglitz later felt sad about this marriage. Emmy did not share his love for art and culture.

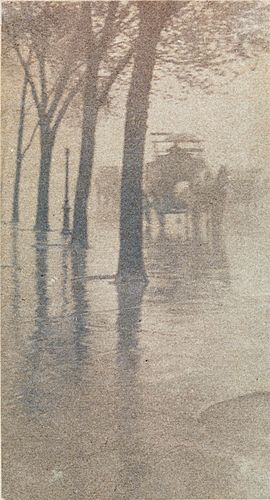

In early 1894, Stieglitz and his wife went on their honeymoon to France, Italy, and Switzerland. Stieglitz took many photos on the trip. He created famous images like A Venetian Canal and A Wet Day on the Boulevard, Paris. In Paris, he met French photographer Robert Demachy. They became lifelong friends. In London, Stieglitz met leaders of The Linked Ring, a group of photographers. They also became his friends.

Later that year, Stieglitz was chosen as one of the first two American members of The Linked Ring. He saw this as a push to promote artistic photography in the U.S. At the time, there were two photo clubs in New York. Stieglitz left his job at Photochrome and as editor of American Amateur Photographer. He spent most of 1895 working to combine the two clubs.

In May 1896, the two groups joined to form The Camera Club of New York. He became vice-president. He created programs and was involved in everything. He told a journalist he wanted to make the club so important that it would help artists get recognized.

Stieglitz turned the Camera Club's newsletter into a magazine called Camera Notes. He had full control over it. The first issue came out in July 1897. It quickly became known as the best photo magazine in the world. For the next four years, Stieglitz used Camera Notes to promote photography as an art form. He included articles on art and beauty. He also showed prints by top American and European photographers.

He continued to take his own photos. In late 1896, he made a collection of his own work called Picturesque Bits of New York and Other Studies. He kept showing his work in Europe and the U.S. By 1898, he was a well-known photographer. He sold his favorite print, Winter – Fifth Avenue, for $75. Ten of his prints were chosen for the first Philadelphia Photographic Salon. There, he met and befriended Gertrude Käsebier and Clarence H. White.

On September 27, 1898, Stieglitz's daughter, Katherine "Kitty", was born. The family hired staff using Emmy's inheritance. Stieglitz worked as much as before. This meant he and Emmy lived mostly separate lives in the same home.

In November 1898, a group of photographers in Munich, Germany, held an exhibit. They called themselves the "Secessionists." Stieglitz liked this name. Four years later, he used it for a new group of photographers he started in New York.

In May 1899, Stieglitz had his own exhibition at the Camera Club. It had eighty-seven of his prints. Preparing for this show and producing Camera Notes made Stieglitz very tired. To help, he brought in friends, Joseph Keiley and Dallet Fugeut, as associate editors. Some older club members were upset by this. They tried to stop Stieglitz's control. Stieglitz spent much of 1900 fighting these efforts.

One good thing that year was Stieglitz meeting a new photographer, Edward Steichen. Steichen was a painter first and brought his artistic ideas to photography. They became good friends and worked together.

Because of the stress of managing the Camera Club, Stieglitz became very ill the next year. He spent much of the summer recovering at his family's Lake George home. When he returned to New York, he announced he was leaving his job as editor of Camera Notes.

The Photo-Secession and Camera Work (1902–1907)

Photographer Eva Watson-Schütze encouraged Stieglitz to create an exhibition. This show would be judged only by photographers. In December 1901, Charles DeKay of the National Arts Club invited Stieglitz to organize a show. Stieglitz had "full power to follow his own inclinations." Within two months, Stieglitz gathered photos from his friends. He called the group the Photo-Secession. This name showed he was breaking away from old art rules and the Camera Club. The show opened in March 1902 and was a big success.

He then planned to publish a magazine about photography. It would be completely independent. By July, he had fully left Camera Notes. A month later, he announced a new journal called Camera Work. He wanted it to be "the best and most beautiful of photographic publications." The first issue was printed in December 1902. Like all later issues, it had lovely photogravures. These were high-quality prints made from etched plates. It also had articles about photography, art, and reviews. Camera Work was the first photo journal to focus on visuals.

Stieglitz was a perfectionist. This showed in every part of Camera Work. He made the quality of photogravure printing much better. The prints were so good that when original photos didn't arrive for a show, prints from the magazine were used instead. Most people thought they were looking at the original photographs.

Throughout 1903, Stieglitz published Camera Work. He also worked to show his own photos and those of the Photo-Secessionists. He also dealt with stress at home. Edward Steichen, a photographer from Luxembourg, was featured most often in the magazine. Stieglitz brought his three associate editors from Camera Notes with him to Camera Work. He later said he personally wrapped and mailed about 35,000 copies of Camera Work.

By 1904, Stieglitz was tired again. He took his family to Europe in May. He planned a very busy trip of shows and meetings. He became ill almost as soon as he arrived in Berlin. He spent over a month recovering. He spent much of 1904 photographing Germany. His family visited relatives there. On his way back to the U.S., Stieglitz stopped in London. He met with leaders of the Linked Ring. But he could not convince them to start a chapter in America.

On November 25, 1905, the "Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession" opened in New York. It had one hundred prints by thirty-nine photographers. Steichen had suggested and encouraged Stieglitz to rent three rooms for a gallery. The gallery was an instant success. Almost fifteen thousand people visited in its first season. They sold nearly $2,800 worth of prints. Work by his friend Steichen, who lived in the same building, made up more than half of those sales.

Stieglitz kept focusing on photography. This was often at the cost of his family life. Emmy, his wife, hoped to earn his love. She continued to give him money from her inheritance.

In the October 1906 issue of Camera Work, his friend Joseph Keiley wrote: "Today in America the real battle for which the Photo-Secession was established has been accomplished – the serious recognition of photography as an additional medium of pictorial expression."

Two months later, Stieglitz, then 42, met 28-year-old artist Pamela Colman Smith. She wanted to show her drawings and watercolors at his gallery. He decided to show her work. He thought it would be helpful to compare drawings and photos. Her show opened in January 1907. It had more visitors than any previous photo shows. All her works sold quickly. Stieglitz took photos of her artwork and made a separate collection of his prints of her work.

The Steerage, 291, and Modern Art (1907–1916)

Stieglitz earned less than $400 that year. This was because Camera Work subscriptions were down and the gallery made little profit. For years, Emmy had lived a fancy lifestyle. This included a full-time governess for Kitty and expensive trips to Europe. Despite her father's worries about money, the Stieglitz family and their governess sailed to Europe again.

On his way to Europe, Stieglitz took a photo that is now one of the most important of the 20th century. He aimed his camera at the poorer passengers in the front of the ship. He captured a scene he called The Steerage. He did not publish or show it for four years.

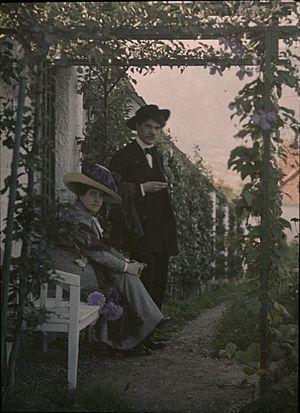

While in Europe, Stieglitz saw the first public showing of the Autochrome Lumière color photography process. Soon, he was trying it out in Paris with Steichen and other photographers.

He was asked to leave the Camera Club. But other members protested, and he was allowed to stay as a life member. After he showed Auguste Rodin's drawings, his money problems forced him to close the Little Galleries for a short time. In February 1908, it reopened with a new name: "291".

Stieglitz purposely mixed exhibitions of art that he knew would cause discussion. The goal was to help visitors compare different types of artists: painters, sculptors, and photographers. He wanted them to see differences and similarities between European and American artists, and between older and newer artists. During this time, the National Arts Club held a "Special Exhibition of Contemporary Art." It included photos by Stieglitz, Steichen, and others. It also had paintings by famous artists like Mary Cassatt. This was likely the first major U.S. show where photographers were seen as equal to painters.

For most of 1908 and 1909, Stieglitz spent his time creating shows at 291 and publishing Camera Work. No photos from this period appear in the main catalog of his work.

In May 1909, Stieglitz's father Edward died. He left his son $10,000 in his will. Stieglitz used this money to keep his gallery and Camera Work going for several years.

During this time, Stieglitz met Marius de Zayas. He was an energetic artist from Mexico. He became one of Stieglitz's closest helpers. He helped with gallery shows and introduced Stieglitz to new artists in Europe. As Stieglitz became known for promoting European modern art, new American artists came to him. They hoped to show their work. Stieglitz liked their modern ideas. Within months, Alfred Maurer, John Marin, and Marsden Hartley all had their art at 291.

In 1910, Stieglitz was asked to organize a big show of the best modern photography. This was for the Albright Art Gallery. Even though an open competition was announced in Camera Work, the fact that Stieglitz was in charge led to new attacks against him. One magazine said Stieglitz could no longer see the value of good photo work that didn't fit his style. They said his group, the Photo-Secession, was no longer progressive.

Stieglitz wrote to a fellow photographer: "The reputation, not only of the Photo-Secession, but of photography is at stake, and I intend to muster all the forces available to win out for us." The exhibition opened in October with over 600 photographs. Critics generally praised the beauty and technical quality of the works. However, his critics noted that most of the prints were from the same photographers Stieglitz had known for years. More than five hundred prints came from only thirty-seven photographers.

In January 1911, Stieglitz reprinted a review of the Buffalo show. It had negative words about photos by White and Käsebier. White never forgave Stieglitz. He started his own photography school. Käsebier and White also helped start the "Pictorial Photographers of America."

Throughout 1911 and early 1912, Stieglitz organized important modern art shows at 291. He promoted new art and photography in Camera Work. By summer 1912, he was so interested in non-photographic art that he published an issue of Camera Work (August 1912) just about Matisse and Picasso.

In late 1912, painters Walter Pach, Arthur B. Davies, and Walt Kuhn organized a modern art show. Stieglitz lent some modern art pieces from 291 to the show. He also agreed to be an honorary vice-president of the exhibition. In February 1913, the very important Armory Show opened in New York. Modern art became a major topic in the city. Stieglitz saw the show's popularity as proof that his work at 291 was important. He held an exhibition of his own photos at 291 at the same time. He later wrote that seeing both photos and modern paintings together helped people understand the place of both art forms.

In January 1914, his close friend and coworker Joseph Keiley died. This made Stieglitz very sad for weeks. He was also worried about World War I. He was concerned for family and friends in Germany. He also needed to find a new printer for Camera Work's photogravures. These had been printed in Germany for years. The war caused the American economy to slow down. Art became a luxury for many. By the end of the year, Stieglitz struggled to keep 291 and Camera Work going. He published the April issue of Camera Work in October. But it would be over a year before he could publish the next one.

Meanwhile, Stieglitz's friends convinced him to start a new project. He published a new journal called 291, named after his gallery. It was meant to be the best of new, modern culture. While it was beautiful, it lost a lot of money and stopped after twelve issues.

During this time, Stieglitz became more interested in a modern look for photography. He saw what was happening in new painting and sculpture. He realized that the old "pictorialism" style was no longer the future. He was influenced by painter Charles Sheeler and photographer Paul Strand. In 1915, Strand showed Stieglitz a new way of seeing photos. It used the strong lines of everyday objects. Stieglitz was one of the first to see the beauty in Strand's style. He gave Strand a big exhibit at 291. He also used almost the entire last issue of Camera Work for Strand's photos.

In January 1916, Stieglitz saw a collection of charcoal drawings by a young artist named Georgia O'Keeffe. Stieglitz loved her art so much that he planned to show her work at 291. He did this without meeting O'Keeffe or even asking her permission. O'Keeffe found out when a friend saw her drawings in the gallery in late May. She finally met Stieglitz when she went to 291 and told him off for showing her work without permission.

Soon after, O'Keeffe met Paul Strand. For several months, she and Strand wrote romantic letters. When Strand told Stieglitz about his feelings, Stieglitz told Strand about his own strong interest in O'Keeffe. Slowly, Strand's interest faded, and Stieglitz's grew. By summer 1917, he and O'Keeffe were writing very personal letters. It was clear something very strong was developing between them.

The year 1917 marked the end of one period in Stieglitz's life and the start of another. Because of changing art styles, the war, and his growing relationship with O'Keeffe, he no longer had the interest or money to continue what he had been doing. Within a few months, he closed the Photo-Secession, stopped publishing Camera Work, and shut down 291. It was also clear his marriage to Emmy was over. He had finally found his "twin soul," and nothing would stop him from the relationship he had always wanted.

O'Keeffe and Modern Art (1918–1924)

In early June 1918, O'Keeffe moved to New York from Texas. Stieglitz had promised her a quiet studio to paint. Within a month, he took the first of many photos of her at his family's apartment. His wife Emmy was away, but she returned while they were still taking pictures. She had suspected something was happening between them. She told him to stop seeing O'Keeffe or leave. Stieglitz left and immediately found a place where he and O'Keeffe could live together.

Once he was out of their apartment, Emmy changed her mind. Because of legal delays caused by Emmy and her brothers, it took six more years for the divorce to be final. During this time, Stieglitz and O'Keeffe continued to live together. She would sometimes go off on her own to create art. Stieglitz used their time apart to focus on his photography and promoting modern art.

O'Keeffe was the inspiration Stieglitz had always wanted. He took photos of O'Keeffe constantly between 1918 and 1925. This was his most productive period. He made over 350 mounted prints of O'Keeffe. These showed many sides of her personality, moods, and beauty. He took many close-up photos of parts of her body, especially her hands. A writer about O'Keeffe said her "personality was crucial to these photographs; it was this, as much as her body, that Stieglitz was recording."

In 1920, Stieglitz was asked to put together a major exhibition of his photographs. This was for the Anderson Galleries in New York. In early 1921, he held his first solo photo exhibit since 1913. Of the 146 prints he showed, only 17 had been seen before. Forty-six were of O'Keeffe, but she was not named as the model. In the catalog for this show, Stieglitz made his famous statement: "I was born in Hoboken. I am an American. Photography is my passion. The search for Truth my obsession."

In 1922, Stieglitz organized a large show of John Marin's paintings. This was at the Anderson Galleries. Then came a huge auction of nearly two hundred paintings by over forty American artists, including O'Keeffe. Feeling energetic, he started one of his most creative projects. He began photographing clouds just for their shape and beauty.

By late summer, he had created a series he called "Music – A Sequence of Ten Cloud Photographs." Over the next twelve years, he would take hundreds of cloud photos. They had no signs of location or direction. These are seen as the first intentionally abstract photographs. They remain some of his most powerful works. He called these photos Equivalents.

Stieglitz's mother Hedwig died in November 1922. As he did with his father, he put his sadness into his work. He spent time with Paul Strand and his new wife Rebecca (Beck). He looked at the work of a new photographer named Edward Weston. He also started organizing a new show of O'Keeffe's work. Her show opened in early 1923. Stieglitz spent much of the spring promoting her work. Eventually, twenty of her paintings sold for over $3,000. In the summer, O'Keeffe went to the quiet Southwest again. For a while, Stieglitz was alone with Beck Strand at Lake George. O'Keeffe returned in the fall. She could tell what had happened. But she did not see Stieglitz's new lover as a serious threat.

In 1924, Stieglitz's divorce was finally approved. Within four months, he and O'Keeffe married in a small, private ceremony. They went home without a party or honeymoon. O'Keeffe later said they married to help Stieglitz's daughter Kitty. Kitty was being treated for depression at the time. For the rest of their lives, their relationship was a "collusion." This meant they had unspoken agreements and trade-offs. O'Keeffe often avoided arguments.

In the coming years, O'Keeffe spent much of her time painting in New Mexico. Stieglitz rarely left New York, except for summers at his family's estate in Lake George. This was his favorite vacation spot. O'Keeffe later said "Stieglitz was a hypochondriac and couldn't be more than 50 miles from a doctor."

At the end of 1924, Stieglitz gave 27 photographs to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. This was the first time a major museum added photos to its permanent collection. That same year, he received an award for advancing photography. He also became an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society.

The Intimate Gallery and An American Place (1925–1937)

In 1925, Stieglitz was asked to create one of the largest exhibitions of American art. It was called Alfred Stieglitz Presents Seven Americans. It showed 159 paintings, photographs, and other items by artists like Arthur G. Dove, John Marin, Paul Strand, Georgia O'Keeffe, and Alfred Stieglitz. Only one small painting by O'Keeffe sold during the three-week show.

Soon after, Stieglitz was offered a room at the Anderson Galleries. He used it for shows by some of the same artists. In December 1925, he opened his new gallery, "The Intimate Gallery." He called it "The Room" because it was small. Over the next four years, he put together sixteen shows. These featured works by Marin, Dove, Hartley, O'Keeffe, and Strand. He also showed works by Gaston Lachaise, Oscar Bluemner, and Francis Picabia. During this time, Stieglitz built a relationship with art collector Duncan Phillips. Phillips bought several works through The Intimate Gallery.

In 1927, Stieglitz became very interested in 22-year-old Dorothy Norman. She was volunteering at the gallery, and they fell in love. Norman was married and had a child. But she came to the gallery almost every day.

O'Keeffe accepted an offer to go to New Mexico for the summer. Stieglitz used her time away to start photographing Norman. He also began teaching her how to print photos. When Norman had a second child, she was away from the gallery for about two months. But she soon returned regularly. Within a short time, they became lovers. Even after their physical relationship lessened a few years later, they continued to work together whenever O'Keeffe was not around. This lasted until Stieglitz died in 1946.

In early 1929, Stieglitz was told the building housing The Room would be torn down. After a final show in May, he went to Lake George for the summer, tired and sad. The Strands raised nearly sixteen thousand dollars for a new gallery for Stieglitz. But he reacted harshly. He said it was time for "young ones" to do some of the work he had been doing. Stieglitz eventually apologized and accepted their help. But this event marked the beginning of the end of their long friendship.

In late fall, Stieglitz returned to New York. On December 15, two weeks before his sixty-fifth birthday, he opened "An American Place." It was the largest gallery he had ever managed. It was the first time he had his own darkroom in the city. Before, he had borrowed other darkrooms or worked only at Lake George. For the next sixteen years, he continued to show group or individual shows of his friends Marin, Demuth, Hartley, Dove, and Strand. O'Keeffe had at least one major exhibition each year. He strongly controlled access to her works. He promoted her constantly, even when critics didn't give her good reviews. Often during this time, they only saw each other in the summer. This was when it was too hot in her New Mexico home. But they wrote to each other almost weekly, like soul mates.

In 1932, Stieglitz held a show of 127 of his works at The Place. It covered forty years of his photography. He included all his most famous photos. But he also purposely included recent photos of O'Keeffe. Because of her years in the Southwest sun, she looked older than her forty-five years. This was compared to Stieglitz's portraits of his young lover Norman. It was one of the few times he acted unkindly to O'Keeffe in public. This might have been because of their growing arguments in private about his control over her art.

Later that year, he showed O'Keeffe's works next to some amateur paintings on glass by Becky Strand. He did not publish a catalog for the show. The Strands saw this as an insult. Paul Strand never forgave Stieglitz for it. He said, "The day I walked into the Photo-Secession 291 [sic] in 1907 was a great moment in my life… but the day I walked out of An American Place in 1932 was not less good. It was fresh air and personal liberation from something that had become, for me at least, second-rate, corrupt and meaningless."

In 1936, Stieglitz briefly returned to his photography roots. He held one of the first exhibitions of photos by Ansel Adams in New York City. The show was successful. David McAlpin bought eight Adams photos. He also put on one of the first shows of Eliot Porter's work two years later. Stieglitz, known as the "godfather of modern photography," encouraged Todd Webb to develop his own style.

The next year, the Cleveland Museum of Art held the first major exhibition of Stieglitz's work outside his own galleries. He worked himself to exhaustion making sure each print was perfect. O'Keeffe spent most of that year in New Mexico.

Last Years (1938–1946)

In early 1938, Stieglitz had a serious heart attack. He would have six heart attacks over the next eight years. Each one left him weaker. When he was absent, Dorothy Norman managed the gallery. O'Keeffe stayed in her Southwest home from spring to fall during this time.

In the summer of 1946, Stieglitz had a fatal stroke and fell into a coma. O'Keeffe returned to New York and found Dorothy Norman in his hospital room. O'Keeffe left, and then she was with him when he died. As he wished, a simple funeral was held for twenty of his closest friends and family. Stieglitz was cremated. O'Keeffe and his niece took his ashes to Lake George. O'Keeffe said they "put him where he could hear the water." The day after the funeral, O'Keeffe took control of An American Place.

Key Set

Stieglitz made over 2,500 mounted photographs in his career. After he died, O'Keeffe gathered what she thought were his best photos that he had personally mounted. Sometimes she included slightly different versions of the same image. These series are very valuable for understanding Stieglitz's artistic choices. In 1949, she gave the first part of what she called the "key set" of 1,317 Stieglitz photographs to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. In 1980, she added another 325 photos Stieglitz took of her. Now with 1,642 photographs, it is the largest and most complete collection of Stieglitz's work. In 2002, the National Gallery published a two-volume catalog. It showed the complete key set with detailed notes about each photo.

In 2019, the National Gallery published an updated online version of the Alfred Stieglitz Key Set.

Legacy

- Stieglitz explained in 1934:

- "Personally I like my photography straight, unmanipulated, devoid of all tricks; a print not looking like anything but a photograph, living through its own inherent qualities and revealing its own spirit."

- Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) is perhaps the most important person in the history of visual arts in America. This doesn't mean he was the greatest artist. But through his many roles – as a photographer, a discoverer and promoter of artists, a publisher, and a collector – he had a greater impact on American art than almost anyone else.

- Alfred Stieglitz had many talents, like a Renaissance man. He had a huge vision. His achievements were amazing, and his dedication was inspiring. He was a brilliant photographer, an inspiring publisher, a great writer, a gallery owner, and an organizer of art shows. He was a leader in the photo and art worlds for over thirty years. He was a passionate, complex, and driven person. He inspired both great love and great dislike.

- Eight of the nine highest prices ever paid at auction for Stieglitz photographs (as of 2008) are images of Georgia O'Keeffe. The highest-priced photograph, a 1919 print of Georgia O'Keeffe - Hands, sold for US$1.47 million in February 2006. At the same sale, Georgia O'Keeffe - Torso, another 1919 print, sold for $1.36 million.

- Many of his works are kept at the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

- In 1971, Stieglitz was added to the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum after his death.

Images for kids

-

Georgia O'Keeffe, Hands, 1918

See Also

In Spanish: Alfred Stieglitz para niños

In Spanish: Alfred Stieglitz para niños

- Photography in the United States

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |