Gertrude Käsebier facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Gertrude Käsebier

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by Adolf de Meyer, c. 1900

|

|

| Born |

Gertrude Stanton

May 18, 1852 Des Moines, Iowa, U.S.

|

| Died | October 12, 1934 (aged 82) New York City, New York, U.S.

|

| Signature | |

Gertrude Käsebier (born Stanton; May 18, 1852 – October 12, 1934) was an American photographer. She became famous for her pictures of motherhood. She also took many portraits of Native Americans. Gertrude helped other women see photography as a good career choice.

Contents

Biography of Gertrude Käsebier

Early Life and Family (1852–1873)

Gertrude Stanton was born on May 18, 1852. Her birthplace was Fort Des Moines, Iowa. Her parents were Muncy Boone Stanton and John W. Stanton. In 1859, her father moved a saw mill to Golden, Colorado. This was during the Pike's Peak Gold Rush. He became successful from the building boom there.

In 1860, eight-year-old Gertrude traveled to Colorado. She went with her mother and younger brother. They joined her father there. That same year, her father became the first mayor of Golden. Golden was then the capital of the Colorado Territory.

Her father died suddenly in 1864. After his death, her family moved to Brooklyn, New York. Her mother opened a boarding house to support them. From 1866 to 1870, Gertrude lived in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. She stayed with her grandmother. She also went to the Bethlehem Female Seminary. Not much else is known about her early years.

Starting a Photography Career (1874–1897)

On her 22nd birthday in 1874, she married Eduard Käsebier. He was a successful businessman in Brooklyn. They soon had three children. Their names were Frederick, Gertrude, and Hermine. In 1884, they moved to a farm in New Durham, New Jersey. They wanted a healthier place to raise their children.

Gertrude later wrote that she was unhappy in her marriage. She and her husband lived separate lives after 1880. This difficult situation later inspired one of her photos. It showed two oxen tied together. She called it Yoked and Muzzled – Marriage.

Even with their differences, her husband helped her financially. She started art school at age 37. This was unusual for women at that time. Gertrude never said why she started art. But she put all her effort into it. In 1889, she moved her family back to Brooklyn. She attended the Pratt Institute of Art and Design full-time. One of her teachers was Arthur Wesley Dow. He was a very important artist and teacher. He later helped her career.

At Pratt, Gertrude learned about Friedrich Fröbel's ideas. He was a 19th-century scholar. His ideas led to the first kindergartens. His thoughts on motherhood greatly influenced Gertrude. Many of her photos showed the strong bond between a mother and child. She was also inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement.

She studied drawing and painting. But she quickly became very interested in photography. Like many art students, she traveled to Europe. She wanted to learn more. In 1894, she studied photography chemistry in Germany. She left her daughters with family in Wiesbaden. She spent the rest of the year in France. There, she studied with American painter Frank DuMond.

In 1895, she returned to Brooklyn. Her husband became very ill. Her family needed more money. So, she decided to become a professional photographer. A year later, she worked for Samuel H. Lifshey. He was a portrait photographer in Brooklyn. She learned how to run a studio there. She also learned more about printing photos.

By this time, she was already very skilled in photography. Just one year later, she showed 150 photographs. This was at the Boston Camera Club. It was a huge number for one artist. These same photos were shown in February 1897. This time, they were at the Pratt Institute.

These successful shows led to another. It was at the Photographic Society of Philadelphia in 1897. She also gave talks about her work there. She encouraged other women to become photographers. She said photography was "especially adapted to them." She noted that women who tried it were finding "gratifying and profitable success."

Photographing the Sioux People

In 1898, Gertrude Käsebier saw Buffalo Bill's Wild West show. It paraded past her studio in New York City. She remembered her respect for the Lakota people. This inspired her to write to William "Buffalo Bill" Cody. She asked to photograph the Sioux tribe members. They were traveling with his show.

Cody and Käsebier both respected Native American culture. They were friends with the Sioux. Cody quickly said yes to her request. She started her project on April 14, 1898. Gertrude's goal was purely artistic. Her photos were not for selling or advertising. They were never used in Buffalo Bill's show booklets.

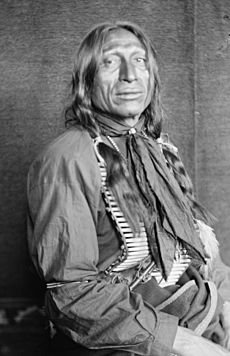

Gertrude took classic photos of the Sioux. They were relaxed in her studio. Chief Iron Tail and Chief Flying Hawk were among her most powerful portraits. Many of Gertrude's photos are kept at the National Museum of American History.

Gertrude had a special story about photographing Iron Tail. The Sioux met to choose their best clothes. They wanted to look good for the photos. Gertrude admired their effort. But she wanted to photograph a "real raw Indian." She meant the kind she saw as a child in Colorado.

Gertrude asked Iron Tail to pose without his fancy clothes. He agreed. The photo showed him relaxed and quiet. It was exactly what she wanted. A few days later, Chief Iron Tail saw the photo. He tore it up, saying it was "too dark." Gertrude photographed him again. This time, he wore all his fine clothes. Iron Tail was a famous person. He had appeared with Buffalo Bill in Paris and Rome. He was a great showman. He did not like the relaxed photo. But Gertrude chose it for a magazine article in 1901. She believed her portraits showed the "strength and individual character" of the Native Americans.

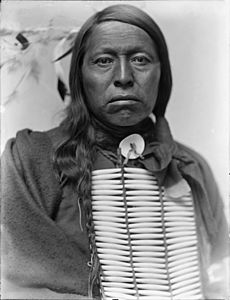

In her photo of Chief Flying Hawk, his serious look stands out. Other photos showed people relaxed or smiling. Flying Hawk had fought in many battles. He was with Crazy Horse at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. He was also at the Wounded Knee Massacre.

In 1898, when the photo was taken, Flying Hawk was new to show business. He was angry about having to act out battle scenes. This was to escape poverty on the reservation. Soon, Flying Hawk learned to like being a Show Indian. He would walk around the show grounds in his full regalia. He sold his postcards to earn extra money. After Iron Tail died in 1916, Flying Hawk became the head Chief of the Indians in Buffalo Bill's Wild West.

Peak of Her Career (1898–1909)

Over the next ten years, Gertrude took many photos of the Indians in the show. Some of these photos became her most famous works.

Unlike Edward Curtis, another photographer of her time, Gertrude focused on people's feelings. She showed their unique personalities. She did not focus as much on their costumes. Edward Curtis sometimes added things to his photos. But Gertrude did the opposite. She sometimes removed items from a person. This was to focus on their face or body.

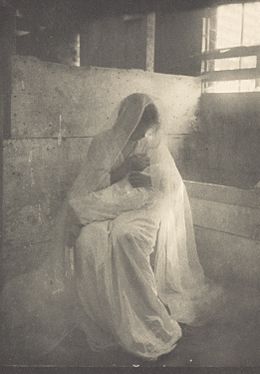

In July 1899, Alfred Stieglitz published five of her photos. He wrote that she was "the leading artistic portrait photographer of the day." Her quick rise to fame was noticed. Another photographer, Joseph Keiley, wrote about her. He said her name was "first and unrivaled." That same year, her photo "The Manger" sold for $100. This was the most ever paid for a photograph at that time.

In 1900, Gertrude continued to receive praise. A photography catalog called her "the foremost professional photographer in the United States." She was also one of the first two women elected to Britain's Linked Ring. This was a famous photography group.

The next year, Charles H. Caffin wrote a book. It was called Photography as a Fine Art. He wrote a whole chapter about Gertrude's work. Because people in Europe wanted her artistic advice, she spent most of 1901 there. She visited with other photographers like F. Holland Day and Edward Steichen.

In 1902, Alfred Stieglitz chose Gertrude as a founding member of the Photo-Secession. This was a group of artists who wanted photography to be seen as fine art. The next year, Stieglitz published six of her photos. They were in the first issue of Camera Work. This magazine showed the best artistic photography. In 1905, six more of her photos were in Camera Work. The next year, Stieglitz showed her photos in his gallery.

Balancing her work and personal life was hard for Gertrude. Her husband moved to Oceanside, Long Island. This made it harder for her to be near the New York art scene. So, she went back to Europe. There, she photographed the famous sculptor Auguste Rodin.

When Gertrude returned to New York, she had a disagreement with Stieglitz. Gertrude needed to earn money to support her family. She was very interested in the business side of photography. But Stieglitz believed art should not be about money. The more successful Gertrude became, the more Stieglitz felt she was going against his ideas. In May 1906, Gertrude joined a new group. It was called the Professional Photographers of New York. Stieglitz saw this group as everything he disliked. After this, he started to distance himself from Gertrude. Their friendship was never the same.

Working Independently (1910–1934)

Eduard Käsebier died in 1910. This finally allowed Gertrude to follow her own path. She continued to work separately from Stieglitz. She also helped start the Women's Professional Photographers Association of America. Stieglitz then began to speak against her newer work. But he still thought her earlier photos were good. He included 22 of them in a big exhibition later that year.

The next year, Gertrude was surprised by a harsh criticism. It came from Joseph T. Keiley. He had admired her before. His criticism was published in Stieglitz's Camera Work. No one knows why Keiley changed his mind. But Gertrude thought Stieglitz might have influenced him.

Gertrude's distance from Stieglitz grew. He did not like the idea of making money from artistic photography. If he felt a buyer truly loved the art, he often sold prints for less money. He also took a long time to pay the photographers. After several years of disagreeing, Gertrude left the Photo-Secession in 1912. She was the first member to resign.

In 1916, Gertrude helped Clarence H. White start a new group. It was called Pictorial Photographers of America. Stieglitz saw this as a challenge to his leadership. But by this time, Stieglitz had upset many of his friends. These included White and Robert Demachy. A year later, Stieglitz had to close the Photo-Secession.

During this time, many young women photographers looked up to Gertrude. They admired her art and her independence. Some of these women became successful photographers themselves. They included Clara Sipprell, Consuelo Kanaga, Laura Gilpin, Florence Maynard, and Imogen Cunningham.

Throughout the 1910s and 1920s, Gertrude's portrait business grew. She photographed many important people. These included artists like Robert Henri and John Sloan. In 1924, her daughter Hermine Turner joined her in the business.

In 1929, Gertrude stopped taking photos. She sold everything in her studio. The same year, she had a big solo exhibition at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences.

Gertrude Käsebier died on October 12, 1934. She passed away at her daughter Hermine Turner's home.

The University of Delaware has a large collection of her work. In 1979, Gertrude Käsebier was added to the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum.

Gallery

-

Miss N

(Portrait of Evelyn Nesbit), 1903 -

Clarence White Sr., 1897–1910 -

Portrait of Alfred Stieglitz, 1902 -

Auguste Rodin, 1905 -

The Clarence White Family in Maine

(American photographer), 1913 -

Rose O'Neill, c. 1907 -

Portrait of Robert Henri (American painter), c. 1907

Additional Reading

- Delaney, Michelle. Buffalo Bill's Wild West Warriors: A Photographic History by Gertrude Käsebier. Smithsonian, 2007. ISBN: 0061129771.

See also

In Spanish: Gertrude Käsebier para niños

In Spanish: Gertrude Käsebier para niños