Flying Hawk facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Flying Hawk

|

|

|---|---|

| Čhetáŋ Kiŋyáŋ | |

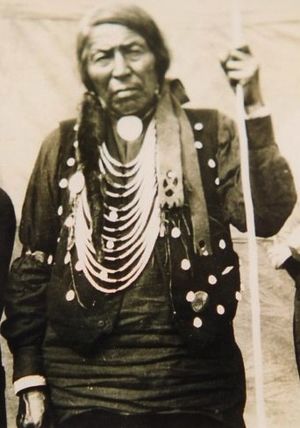

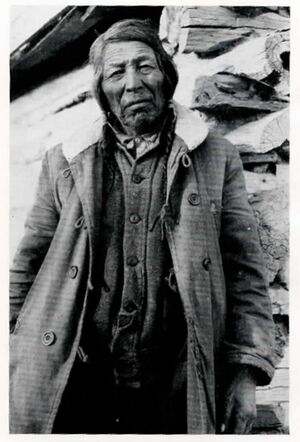

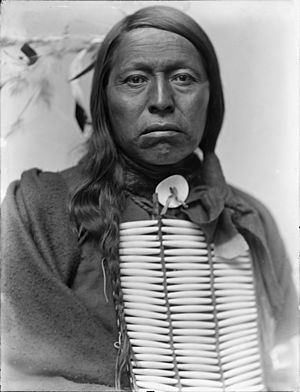

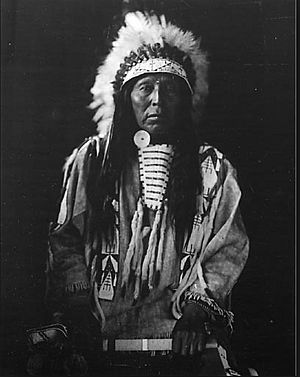

Chief Flying Hawk, Čhetáŋ Kiŋyáŋ.

|

|

| Oglala Lakota leader | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 1854 Rapid Creek, Lakota Territory |

| Died | December 24, 1931 (aged 77) Pine Ridge, South Dakota |

| Spouses | White Day Goes Out Looking |

| Relations | Kicking Bear (brother) Black Fox II (half brother) Crazy Horse (first cousin) Sitting Bull (uncle) |

| Children | Felix Flying Hawk (son) |

| Parents | Black Fox (father) Iron Cedar Woman (mother) |

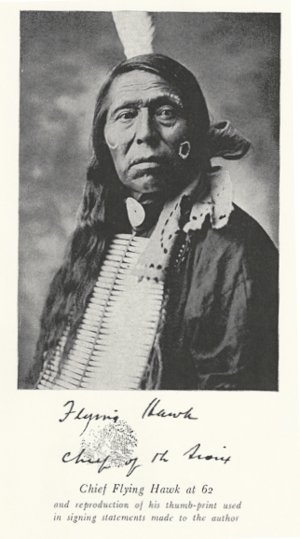

Flying Hawk (Oglala Lakota: Čhetáŋ Kiŋyáŋ; also known as Moses Flying Hawk; March 1854 – December 24, 1931) was an Oglala Lakota warrior, historian, teacher, and thinker. His life story shows the history of the Oglala Lakota people in the 1800s and early 1900s. He worked hard to protect his people from the challenges of white settlement. He also aimed to educate them and keep their sacred lands and traditions safe. Chief Flying Hawk fought in Red Cloud's War and most battles against the U.S. Army during the Great Sioux War of 1876.

He fought alongside his first cousin Crazy Horse and his brothers Kicking Bear and Black Fox II. This was at the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876. He was also there when Crazy Horse died in 1877 and at the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890. Chief Flying Hawk was one of five warrior cousins who made sacrifices for Crazy Horse at the Last Sun Dance of 1877. He wrote down his memories of these events and about Native American leaders who defended their families and culture. Flying Hawk traveled for over 30 years with Wild West shows, from about 1898 to 1930. He believed that public education was important to keep Lakota culture alive. He often visited schools to give talks. Chief Flying Hawk left behind important Native American ideas. His "winter count" tells nearly 150 years of Lakota history.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Family Connections

Flying Hawk was born in March 1854, near Rapid Creek, Lakota Territory. His father was Oglala Lakota Chief Black Fox. Black Fox had two wives, who were sisters, and they had thirteen children. Flying Hawk's mother was Iron Cedar Woman, the younger sister, and she had five children.

Black Fox was shot with an arrow in a fight with the Crows. It was so deep it had to be pushed through his ear. He died when he was about eighty years old. Flying Hawk said they later found the rusted arrow-point still in his skull. Kicking Bear (born around 1846) was Flying Hawk's older brother. Kicking Bear was a famous warrior and a leader of the Ghost Dance. Black Fox II was Flying Hawk's half-brother, named after their father.

Crazy Horse was Flying Hawk's first cousin. Even though Crazy Horse was nine years older, they were very close friends. Crazy Horse's mother, Rattling Blanket Woman, was the sister of Iron Cedar Woman, Flying Hawk's mother. Flying Hawk would have called Crazy Horse ciye, meaning 'elder brother'. Sitting Bull was Flying Hawk's uncle. Flying Hawk's mother, Iron Cedar Woman, and Sitting Bull's wife were sisters. When he was 26, Flying Hawk married two sisters, Goes Out Looking and White Day. Goes Out Looking had one son, Felix Flying Hawk.

Youth and Battles

Flying Hawk was young when settlers moved into Sioux lands after the American Civil War. He wanted to be a Chief like his father and brother. As a young man, Flying Hawk led many war parties with his older brother Kicking Bear. They fought against the Crows and the Piegan tribes.

He recalled his first battle at age ten on the Tongue River. It was against soldiers guarding covered wagons. He said the soldiers fired first, and his tribe fought back. He didn't know how many soldiers died, but four of his people were killed. After that, they had many more battles.

When he was twenty, he led a group to steal horses from the Crows. The Crows followed them, but Flying Hawk led his group to fight back. He killed one Crow warrior and took his field glass and necklace. They got the horses home safely. Flying Hawk became a Chief when he was thirty-two. To become a Chief, a warrior had to perform many brave deeds and capture many horses.

Great Sioux War of 1876

The Great Sioux War of 1876-1877 was a series of battles involving the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne tribes. Gold miners rushed to the Black Hills of South Dakota, which were sacred lands. War began when Native Americans, led by Chiefs Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, left their reservations to defend their lands.

Flying Hawk fought in Red Cloud's War (1866-1868). He also fought in almost all the battles against U.S. troops during the Great Sioux War. He fought with his cousin Crazy Horse and brothers Kicking Bear and Black Fox II at the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876. He was one of the five warrior cousins who made sacrifices for Crazy Horse at the Last Sun Dance of 1877. Flying Hawk was present when Crazy Horse died in 1877 and at the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890.

Sun Dance of 1877

Crazy Horse was honored at the Sun Dance in 1877, a year after the victory at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Prayers and sacrifices were made for Crazy Horse to be strong. Crazy Horse attended as the honored guest but did not dance himself. His five warrior cousins danced and sacrificed for him. These were the three brothers: Flying Hawk, Kicking Bear, and Black Fox II. The other two cousins were Eagle Thunder and Walking Eagle.

The Sun Dance is a Lakota religious ceremony. Only very brave warriors would take part. It meant offering their own body in sacrifice. They would endure great physical pain for their prayers to be answered. These prayers might be to prevent famine, or to gain strength in battle. After being tied to the Sun Dance pole through their chest flesh, participants danced for days without food, water, or sleep.

A marker of five rocks was placed at the ceremonial grounds in Nebraska. It honored War Chief Crazy Horse. It also remembered the five Lakota tribes and the five warrior cousins who sacrificed for Crazy Horse.

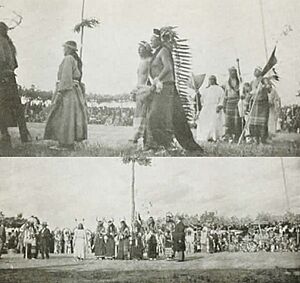

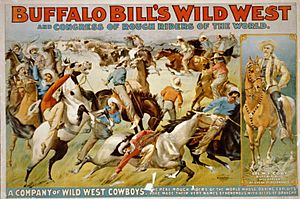

Wild West Shows

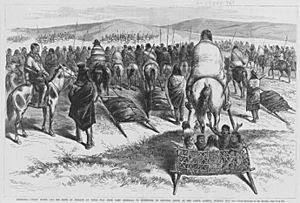

In the late 1890s, Flying Hawk joined Buffalo Bill Cody's Wild West show. Wild West shows were popular with the Lakota people. They offered opportunities when Native Americans faced many challenges. Between 1887 and World War I, over 1,000 Native Americans performed with Buffalo Bill's Wild West. Most were Oglala Lakota from Pine Ridge, South Dakota. Buffalo Bill Cody used his influence to get Native American performers for his show.

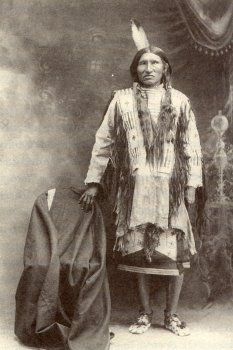

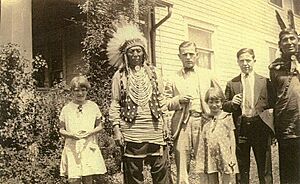

Chief Flying Hawk was used to being welcomed by important people in Europe and America. After Chief Iron Tail died in 1916, Flying Hawk was chosen to lead the Native American performers in Buffalo Bill's Wild West. He led the parades as the head Chief.

In the big street parades, Buffalo Bill rode a white horse at the front. Beside him, Flying Hawk rode a pinto pony in his full Chief's clothing. He carried his feathered staff, and his eagle-quill bonnet hung down to his saddle.

Buffalo Bill died in January 1917. At his grave on Lookout Mountain, Chief Flying Hawk placed his war staff of eagle feathers on the grave. Other veteran performers placed a Buffalo nickel on the stone. This symbolized the Indian, the buffalo, and the scout, important figures of the American West.

Later, Flying Hawk performed with the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Show and the Sells Floto Circus. He was likely the longest-traveling performer, touring for over 30 years across the United States and Europe.

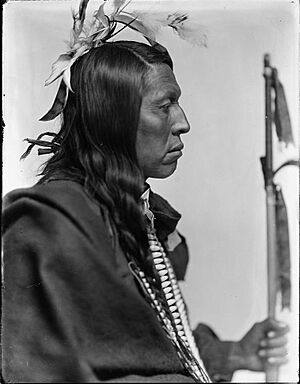

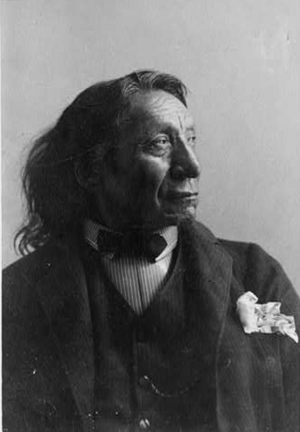

Chief Flying Hawk and Gertrude Käsebier

Gertrude Käsebier was a famous American photographer in the early 1900s. She was known for her photos of Native Americans. She grew up on the Great Plains and played with Sioux children. In 1898, Käsebier saw Buffalo Bill's Wild West show parade in New York City. She remembered her respect for the Lakota people. She wrote to Buffalo Bill, asking to photograph the Sioux performers in her studio.

Cody and Käsebier both respected Native American culture. Cody quickly agreed. Käsebier started her project in April 1898. Her goal was purely artistic; her photos were not for show programs or ads.

Käsebier took classic photos of the Sioux when they were relaxed. Chief Flying Hawk was one of her most challenging subjects. His serious gaze is very striking in her portraits. Other Native Americans could relax or pose. Chief Flying Hawk had fought in many battles during the Great Sioux War of 1876. He fought with Crazy Horse and his brothers at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. He was also at the death of Crazy Horse and the Wounded Knee Massacre.

In 1898, Flying Hawk was new to show business. It was hard for him to hide his anger about having to re-enact battles from the Great Plains Wars to escape poverty on the reservation. But soon, he learned to appreciate being a "Show Indian." He often walked around the show grounds in his full clothing. He sold his picture postcards for a penny to help promote the show and earn extra money. After Chief Iron Tail died in 1916, Chief Flying Hawk became the head Chief of the Native American performers.

The Wigwam

The Wigwam, the home of Major Israel McCreight in Du Bois, Pennsylvania, was like a second home for Chief Flying Hawk for nearly thirty years. It was a large estate with forests. It was a place for Oglala Lakota Wild West performers to rest. It was also a retreat for important people like politicians and journalists. Du Bois was a railroad hub, making it a good stop for travelers. For "Old Scouts" like Buffalo Bill Cody, The Wigwam was a place to relax and talk about the Old West.

Wild West performers needed a place to relax. The Wigwam was a welcoming home where Native Americans could be themselves. They could sleep in buffalo skins and tipis, walk in the woods, and tell stories. Once, 150 Native Americans from Buffalo Bill's Wild West show camped in the forests at The Wigwam. Chiefs Iron Tail and Flying Hawk thought of The Wigwam as their home in the East. Many other Oglala Lakota Chiefs visited, including American Horse, Blue Horse, and Rain-In-The-Face. Even Crow Chief Plenty Coups visited.

At The Wigwam, Chief Flying Hawk could rest. Show tours were very tiring, with two performances daily. Traveling, pony riding, and war dances affected his health. Here, he could wake up with the sun, walk in the forest, and enjoy a good breakfast. He would smoke his pipe and relax. Chief Flying Hawk preferred to sleep on the enclosed sun porch with his robes and blankets. He did not want to sleep on a "white man's mattress."

McCreight was impressed by Chief Flying Hawk's grace. He described how the Chief would carefully comb and oil his long hair, then apply a little paint to his cheeks. Flying Hawk's hair, still reaching his waist, was streaked with gray. He said that long ago, Native Americans often had hair that reached the ground.

Even in this relaxed setting, visits had a formal side. Flying Hawk was an Oglala Lakota Chief, and it was his duty to display his eagle feather "Chief’s Wand." One morning, he was seen coming from the forest with a six-foot green stick. He attached his beautiful eagle feather streamer to it. He told McCreight to keep it where it could always be seen, so people would know he was Chief.

Chief Flying Hawk's Commentaries

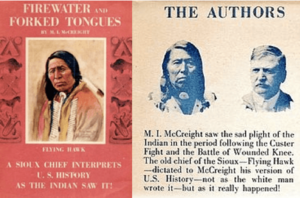

After Chief Flying Hawk died in 1931, McCreight spent his life sharing the Chief's story. In 1936, McCreight published Chief Flying Hawk’s Tales: The True Story of Custer’s Last Fight. He followed this with The Wigwam: Puffs from the Peace Pipe in 1943. In 1947, at age 82, McCreight published Firewater and Forked Tongues: A Sioux Chief Interprets U.S. History.

Writing the Commentaries

Chief Flying Hawk took his role as a chief seriously. He always thought about what was best for his people. He believed that educating young people was key to preserving Lakota culture. He often visited schools to give talks. Flying Hawk wanted to share the true history from a Native American point of view. He felt that white men's books about Native Americans were not always truthful. Major Israel McCreight had lived with the Oglala Lakota during difficult times. He wanted to tell the story of Native Americans who bravely defended their homes and families.

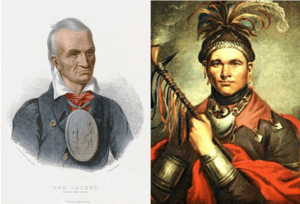

For nearly 30 years, Flying Hawk visited McCreight at The Wigwam. Together, they worked to write a Native American view of U.S. history. Chief Flying Hawk's stories included accounts of the Battle of the Little Big Horn, Crazy Horse, and the Wounded Knee Massacre. He also shared his thoughts on the European settlement of America. He spoke about Native American leaders who fought to protect their families and culture. These included Red Jacket, Little Turtle, Logan, Cornplanter, Osceola, Red Bird, Pontiac, Tecumseh, Black Hawk, Red Cloud, and Sitting Bull. Flying Hawk was interested in current events and supported Native American rights.

During their visits, Flying Hawk and McCreight would light their pipes and talk about Native American history. McCreight would write down notes, hoping to publish them one day. McCreight had a large library of books on U.S. history and Native American treaties. Flying Hawk would often ask for these materials to be translated for him.

They had a special way of working together. First, Chief Flying Hawk would speak to McCreight through one of his interpreters, Chief Thunder Bull or Jimmy Pulliam. He used his Lakota language and Native American sign language. McCreight was impressed by Flying Hawk's powerful speeches. Next, McCreight would write down the information. Then, an interpreter would read it back to the Chief for his corrections and approval. Finally, Flying Hawk would sign the pages with his thumbprint. He would then hand them to McCreight, nod, and say the "paper-talk" was "Washta" (good).

In September 1928, Chief Flying Hawk made one of his last visits to The Wigwam. He was 76 and very ill. He felt he was nearing the end of his life. He wanted to review his old notes and add new stories, hoping they would be published. He said he wanted to tell the "Indian’s side of things" because white people had not told the truth. He believed young people should know the truth about history. The Wigwam helped him regain his strength. He finished his work sessions before returning to the Black Hills. McCreight finished his first draft of Chief Flying Hawk’s Tales that month. However, publishers were not interested at the time. Flying Hawk died on December 24, 1931, at his home in Pine Ridge, South Dakota. He did not live to see his book published. McCreight then dedicated his life to telling the Chief's story.

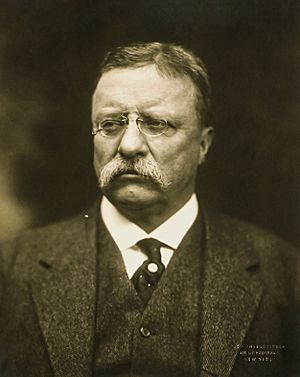

President Theodore Roosevelt's Challenge

McCreight's second book of Flying Hawk's stories, Firewater and Forked Tongues: A Sioux Chief Interprets U.S. History, came out in 1947. This book had more stories not in the first one. The book's dedication quotes President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt said he wished someone would write a true history of how the U.S. dealt with Native Americans. He believed Native Americans had suffered great injustice. Flying Hawk's books were a response to President Roosevelt's challenge. Both men had met President Roosevelt. Chief Flying Hawk met every President since James A. Garfield and liked Theodore Roosevelt the most.

Chief Flying Hawk as Historian

Chief Flying Hawk was one of the last great Oglala Lakota chiefs from the Sioux Wars. He was very knowledgeable about the Great Sioux War. This war started with settlers moving onto their lands, which were protected by treaties. It ended with the Wounded Knee Massacre. He lived through the difficult times after gold was found in the Black Hills.

He was young when white settlers came into Sioux country after the Civil War. He was Sitting Bull's nephew. His brother, Kicking Bear, was a leader of the Ghost Dances. As a boy, he fought in tribal wars against the Crows and Piegans. He fought alongside Crazy Horse when Custer was defeated at the Little Big Horn in 1876. He was Crazy Horse's first cousin. He fought in nine battles with Crazy Horse and won them all.

Chief Flying Hawk was also a skilled leader. He traveled as a main performer with Buffalo Bill's Wild West and other shows for over 30 years. He was used to grand welcomes. In Europe, he met royalty. In America, he met many important people. He met ten U.S. Presidents. He liked Theodore Roosevelt the best.

Native American History and Leaders

Chief Flying Hawk spoke about many topics. These included early Native American civilizations and European explorers like Christopher Columbus. He also discussed massacres of Native Americans at places like Sand Creek and Wounded Knee.

He also commented on early Pennsylvania history during his visits to The Wigwam. He admired William Penn for wanting fair treatment for Native Americans. Flying Hawk believed if Penn's followers had obeyed him, there would have been no wars in Pennsylvania. But when they started taking Native American land, like in the Walking Purchase, Native Americans fought back.

Chief Flying Hawk believed that teaching young people was important for keeping Lakota culture alive. He wanted school history programs to tell the stories of Native American warriors and leaders. These leaders fought to protect their families, lands, and culture. He chose leaders from different tribes. These included Red Jacket (Seneca), Little Turtle (Miami), Logan (Oneida), Cornplanter (Seneca), Osceola (Seminole), Red Bird (Winnebago), Pontiac (Ottawa), Tecumseh (Shawnee), Black Hawk (Sauk), Red Cloud (Lakota), and Sitting Bull (Lakota). Flying Hawk was impressed by their speeches and asked for them to be included in his commentaries.

The Seneca Chiefs

Chief Flying Hawk once visited the Seneca tribe in New York. He greatly admired their Chiefs Cornplanter and Red Jacket. He wanted to include something about them in his writings. When McCreight told him that Cornplanter's father was white, Flying Hawk smiled and said, "That is why he amounted to something." Flying Hawk asked for Red Jacket's speech on "Religion for the White Man and the Red" to be included.

Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull was Flying Hawk's uncle. Flying Hawk's mother and Sitting Bull's wife were sisters. Flying Hawk knew him well. He said Sitting Bull was a key planner before and after battles. Crazy Horse, his young War Chief, led the fighting. Sitting Bull was not in the Custer fight itself. Flying Hawk said Sitting Bull was a strong speaker, like a white senator. He was a good politician.

Flying Hawk was angry about Sitting Bull's death. He believed Sitting Bull would have done anything the agent or Colonel Cody asked. He said there was no need to arrest him. Sitting Bull was celebrating the coming of a new Christ who would bring back the buffalo. This would bring peace and plenty, instead of hardship and hunger.

Flying Hawk said, "Sitting Bull was all right but they got afraid of him and killed him. They were afraid of my cousin Crazy Horse, so they killed him. These were the acts of cowards. It was murder. We were starving. We only wanted food."

Red Cloud

Chief Flying Hawk called Red Cloud "The Red Man’s George Washington." Flying Hawk fought with Crazy Horse in Red Cloud's War. Chief Red Cloud defeated the U.S. Army in battle. The Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868) was a big victory. U.S. Army forts in the Powder River Country were left, and the hunting grounds of the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho were protected. Flying Hawk believed Red Cloud was one of the wisest Native American leaders.

Red Cloud knew what was best for his people. He tried to keep peace with the white settlers, but it didn't work. The settlers kept coming into Native American lands. They took gold and killed all the game. This started the long, bloody war. After the Wounded Knee Massacre, Red Cloud gave a speech. Flying Hawk asked for this speech to be read to him. He wanted it included in his commentaries to explain why they fought Custer and about the Ghost Dance.

Crazy Horse

Memories of Crazy Horse

Flying Hawk said, "Crazy Horse was a great leader. White men who fought him spoke highly of him. His word was trusted by everyone. His own people honored him, and his enemies respected him. They hunted him, but they murdered him because they couldn't defeat him."

Crazy Horse was born in South Dakota in 1844. He was well-trained as a youth. He grew up to be handsome and strong. He was modest and polite, a natural leader. His name came from his personality, like a wild horse. He was an excellent horseman. At sixteen, he joined a war party against the Gros Ventres. When the Chief's horse was shot, Crazy Horse rescued him, both escaping on the boy's horse.

When he was still under twenty, he hunted alone in winter. He brought back ten buffalo tongues for a council feast. He caught them all with his bow and arrows.

Crazy Horse told Flying Hawk a story: He was sitting on a hill when something touched his head. It was a blade of grass. He followed a trail to water and sat in it. When he came out, he felt like he was born again. He understood things for a time. He grew up normally. At seven, he began to learn, and at twelve, he started fighting enemies. This is why he never wore fancy war clothes, only a bit of grass in his hair. This is why he always won battles. His first fight was with the Shoshones.

Crazy Horse's younger brother, Little Hawk, was killed by white settlers in Utah. When Crazy Horse learned this, he went to the place alone. He stayed there nine days, shooting anyone he saw. He killed enough to feel satisfied, then returned home.

Flying Hawk said, "Crazy Horse was never with other Native Americans unless it was in a fight. He was always the first in a fight, and the soldiers could not beat him. He won every fight with the whites."

Crazy Horse was married but had no children. He was often alone. He never told stories. Flying Hawk called him the bravest Chief they ever had. He was the leader and first in the Custer fight. He never talked much but always acted first. Flying Hawk said, "He was my friend and we went in the Custer fight together."

Crazy Horse never wore flashy clothes, feathers, or paint. He never took part in public shows or dances. He was not a public speaker and never gave a speech. He never posed for a photograph. Yet, as a War Chief, he won every battle he fought.

Flying Hawk said, "I have been in nine battles with Crazy Horse; won them all. Crazy Horse was quiet and didn't mix much with others. He was at the front of every battle. He was the greatest leader of our tribe." He called him a "master of strategy."

As Crazy Horse grew up, trouble with white settlers began. The Great Sioux War started. Leaders like Spotted Tail and Red Cloud decided they had to fight. When the government built Fort Phil Kearny in the buffalo hunting grounds, Crazy Horse led the effort to drive out the invaders. His attack on the Fetterman party showed his great strategy.

After that, the war spread. Crazy Horse became a feared opponent for the U.S. Army. Other tribes saw him as a leader. For years, his group was hunted. Soldiers tracked them like wild animals, attacking them in their tipis. Every effort was made to capture or kill Crazy Horse and his people, but they failed.

The Battle of the Little Big Horn

The government gathered a large army. General Crook came from the south, Gibbon from the west, and Custer's cavalry joined Terry's division. They planned to surround the tribes. Crook met Native Americans near the Rosebud River. Crazy Horse fought him so hard that Crook turned back. His army never met up with the others.

From there, Crazy Horse took his group to the Little Big Horn. They hoped to be left alone. But Terry's troops, including Custer's cavalry, found their camps. The other army divisions were not there. Custer decided to attack alone. Reno was ordered to attack the camp upstream. Custer went down the east side to attack where more villages were. He didn't know that Crazy Horse had already stopped Crook's army.

The Native Americans were camped along the west side of the Big Horn in a flat valley. They saw dust but didn't know what it was. Some thought it was soldiers. The Chief saw a flag on a hill. Soldiers formed a line and fired into their tipis, where women and children were. That was the first they knew of trouble. Women grabbed their children and ran.

Native American men quickly got their horses and guns. Kicking Bear and Crazy Horse led the charge. They fought the soldiers in the thick timber. Flying Hawk said, "We got right among the soldiers and killed a lot with our bows and arrows and tomahawks. Crazy Horse was ahead of all, and he killed a lot of them with his war-club. Kicking Bear was right beside him and killed many too in the water."

This fight was in the upper part of the valley. It was some of Reno’s soldiers who attacked them there. It was just before dinner. When the Native Americans attacked, the soldiers tried to run into the timber and cross the water. The bank was steep, and they tried to climb out on their hands and knees. But the Native Americans killed almost all of them as they ran through the woods and in the water. The ones who crossed the river and got up the hill dug holes and stayed in them.

Crazy Horse and Flying Hawk were in the upper village when Reno's troops fired on the tipis. This was the first warning they had of soldiers nearby.

The Native Americans could have wiped out Reno's soldiers, just like Custer's. But Reno had dug in and seemed ready to quit. So, the Native Americans decided to leave them. They went to check on their women, children, and elders who had not been killed. They packed their belongings and left the area.

Soldiers on the hill with pack-horses began to fire. By this time, all the Native Americans had their horses and weapons. They charged the soldiers on top of the hill. Custer was further north. He was going to attack the lower end of the village. The Native Americans drove most of the soldiers down the hill.

Crazy Horse and Flying Hawk rode along the river. They found a ravine and followed it behind the soldiers. Crazy Horse gave his horse to Flying Hawk to hold. He crawled up the ravine to see the soldiers. He shot them as fast as he could. They fell off their horses quickly. When the soldiers saw how fast they were dying, the rest ran to other soldiers further along the ridge toward Custer. They tried to make another stand, but the Native Americans pushed them toward Custer. They made a third stand, but then joined Custer's men.

Other Native Americans joined them. They chased the soldiers until they reached Custer. Only a few were left. By then, all the Native Americans in the village were watching Custer. When Custer got near the lower end of the camp, he tried to go down a gulch. But the Native Americans surrounded him, and he tried to fight. They got off their horses and made a stand, but it was useless. Their horses ran into the village. The women caught them. One was a sorrel horse with white stockings. Later, relatives said they had seen Custer on that kind of horse.

Flying Hawk said, "When we got them surrounded the fight was over in one hour. There was so much dust we could not see much. But the Indians rode around and yelled the war-whoop and shot into the soldiers as fast as they could until they were all dead." One soldier ran away, but Crazy Horse chased him and killed him about half a mile away. When the smoke cleared, they took rings, money, watches, clothes, guns, and pistols from the soldiers. They got seven hundred guns and pistols. Then they went back to their women and children.

Flying Hawk said the story about Custer's heart being cut out was not true. He said, "There was more than one Chief in the fight. But Crazy Horse was leader and did most to win the fight along with Kicking Bear." He named the Chiefs in the fight as Crazy Horse, Lame Deer, Spotted Eagle, and Two Moon (who led the Cheyennes). Gall and other Chiefs were there, but those were the main leaders. Sitting Bull was not in the Custer fight, but he was a main advisor before and after the battle.

Flying Hawk said, "We got our things packed up and took care of the wounded the best we could, and left the next day. We could have killed all the men that got into holes on the hill, but they were glad to let us alone, and so we let them alone too." Rain-in-the-Face was with him. There were about 1,000 to 1,200 Native Americans in the fight. Many were out hunting.

After the Custer Fight

Sitting Bull and his people went to Canada to escape the U.S. Army after Custer's defeat. But Crazy Horse stayed, still fighting his enemies. His people suffered greatly from lack of food in the harsh winter. The army kept tracking them. Crazy Horse had women and children with him, and he had to find food, warm clothes, and shelter for them.

Crazy Horse decided to accept the reservation authorities' offer. They promised supplies and fair treatment if he surrendered. So, in July 1877, he and thousands of his followers came to the reservation. They had one clear condition: the government would listen to their claims.

Instead, General Crook immediately recognized Spotted Tail as the head Chief. Spotted Tail had turned against his own people and supported the army. This made almost all the reservation Native Americans bitter. The government failed to provide promised food and supplies. This caused arguments between Spotted Tail's supporters and Crazy Horse's followers. Those in power at the agency blamed Crazy Horse. They feared he might lead his people to freedom again. So, a plan was made to kill him.

Friends warned Crazy Horse, but he said, "only cowards and murderers" and continued his daily life. His wife was very ill, so he took her to her parents at Spotted Tail Agency. While he was gone, his enemies spread rumors that he had left to start another war. Scouts were sent to arrest him. They found him in a wagon with his sick wife. He was allowed to take her to her parents.

Crazy Horse returned willingly, not expecting any betrayal. When he reached the agency, a guard told him to enter the guard-house. His cousin, Touch-the-Cloud, warned him, "They are going to put you in the guard-house!" Crazy Horse stopped and said, "Another white man’s trick, let me go." But guards held him. When he tried to break free, a soldier stabbed him with a bayonet. He died that night. His father sang a death song over him. His family carried his body to a secret cave. They said no white man should touch it.

Flying Hawk said, "I was present at the death of Crazy Horse; he was my cousin; his father and his two wives and an uncle of Crazy Horse took the body away, and no one knows today where he is buried. Several years later, they went to see how the body was, and when the ground was removed, they found the bones, and they were petrified; they would never tell where they buried him."

He repeated, "Crazy Horse was a great leader. White men who contended with him and knew him well, spoke of him in the highest terms. His word was not called into question by either white men or red. He was honored by his own people and respected by his enemies. Though they hunted and persecuted him, they murdered him because they could not conquer him."

Native American Rights

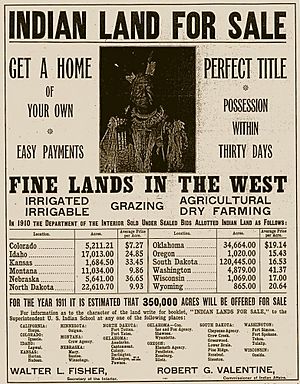

Chief Flying Hawk cared about current events and supported Native American rights. The Sioux never accepted that the Black Hills were taken from them. In 1920, Sioux supporters convinced Congress to allow a lawsuit against the U.S. government. In 1923, Chief Flying Hawk, with McCreight's help, asked the Council to file the case of United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians.

Later, McCreight asked Flying Hawk about the case. Flying Hawk wanted it clear that the treaty with Napoleon was broken when his country was bought. He said that from the beginning, white people had ignored their promises to the Sioux.

McCreight studied the treaties between the Sioux Nation and the United States. He became an expert on Native American issues. He traveled to Washington, D.C., to help the lawyers for the Sioux Nation. Chief Flying Hawk knew about the legal claims. He asked for his commentaries to include the unfair dealings that happened with land purchases from the Sioux tribe. The legal fight between the Sioux and the government continued for many years.

Chief Flying Hawk’s Winter Count

Chief Flying Hawk was a Lakota historian. He created a "winter count" that covered almost 150 years of Lakota history. Lakota years are counted from the first snow of one winter to the first snow of the next. Each year is named after an important or unique event that would be easy to remember. For example, Flying Hawk's Winter Count for 1866 records the Fetterman Fight as "Wasicu opawinge wica ktepi," meaning "They killed one hundred white men." For 1876, it's "Marpiya llute sunkipi," meaning "They took horses from Red Cloud." For 1877, it's "Tasunka witko ktepi," meaning "When they killed Crazy Horse." And for 1890, it's "Si-tanka ktepi," meaning "When they killed Big Foot" (the Wounded Knee Massacre). Chief Flying Hawk specifically asked for his Lakota calendar to be included in his commentaries.

Last Visit to The Wigwam

On Sunday, June 23, 1929, Chief Flying Hawk made his last visit to The Wigwam. McCreight sent him clothes because he had lost all his belongings while performing. Saturdays and Sundays were days off for the performers. The show was in Oil City, Pennsylvania, the next day. McCreight arranged for Flying Hawk to visit and provided transportation. Chief Flying Hawk was with his friend and interpreter, Chief Thunder Bull.

The Old Chief wanted to smoke. The Red Cloud peace-pipe was brought out. They smoked a mix of red-willow bark and tobacco, called kinnikinnick. The Chief enjoyed it as he remembered important treaty councils with government agents. He said the agents always spoke with "forked tongues" and didn't always keep their promises.

It was Sunday, and Flying Hawk's visit was ending. He had woken up with the sun and walked in the woods to see squirrels and hear birds. After breakfast, the Chief wanted to go to church. A car took them to a large Catholic church. The Chief, dressed in his best clothes and a little paint on his face, sat beside his host. During the service, he responded with dignity. He attracted everyone's attention. After the service, Father McGivney welcomed him. It was a long time before the Chief could leave, as friends and neighbors gathered to shake his hand. The Chief was sad to leave. He said he likely would not come again. He felt he would soon join his friends in the Sand Hills.

Chief Flying Hawk's Teachings

Flying Hawk left behind a legacy of Native American wisdom and spiritual teachings:

- "The white man does not obey the Great Spirit; that is why the Indians never could agree with him."

- "White people fight among themselves about religion; for this they have killed more than in all other wars. Did you ever hear of Indians killing each other about worshiping the Great Spirit?"

- "Does the white man know who is right if the Indian says his great grandfather was a bear, and the white man says his great grandfather was a monkey?"

- "The tipi is much better to live in. Always clean, warm in winter, cool in summer, easy to move. The white man builds big house, costs much money, like big cage, shuts out sun, can never move; always sick. Indians and animals know better how to live than white man. Nobody can be in good health if he does not have all the time fresh air, sunshine and good water. If the Great Spirit wanted men to stay in one place he would make the world stand still. But he made it to always change, so birds and animals can move and always have green grass and ripe berries, sunlight to work and play, and night to sleep. Summer for flowers to bloom, and winter for them to sleep; always changing; everything for good; nothing for nothing."

- "The white people will soon be gone. They go so fast they do not take time to live. But they will learn maybe before they all die. Now they are taking a lesson from the Indian. They make their wigwam on wheels and go on the trail like red people do. Indians make travois and pony pull their tipi. White man’s gas car pull his tipi where he wants to go. Soon they learn Indian’s way the best way; no good to stay in one place all of the time."

- "When the Indian wants a woman, he goes to her father and pays him his price. The white man takes one without pay to her father, but hires a preacher to tie her to him. When he is tired of her, he pays a lawyer to untie the rope so he can catch another one. Which good, which bad?"

- "The whites have got rich from controlling the colored people of the world. But they got into debt to each other and now they fight among themselves. Soon they will destroy themselves and the original races will go on in the way the Great Spirit made them to do so."

- "White people do not know how to handle fire. They make big fire and smoke and get little heat. Indians make little fire and get plenty heat. Their pipe is a high bowl with little hole for tobacco and a long stem. Little fire, little heat, smoke always cool when it gets to end of mouthpiece."

- "The Great Spirit, the Sun, makes all life. Without it nothing would grow, no birds, no animals, no people. Indians go to the Happy Hunting Ground when they die. Whites do not know where they go when they die."

- "White folks have so many different kinds of religion and churches and preachers the Indians could not tell which was good and which was no good. So they hold fast to their own."

- "The whites tell the Indian that it is wrong to kill, to fight, to lie and steal or to drink strong liquor. And then they give him bad liquor and steal from him and lie to him and cheat him all the time."

- "The whites got the Indians to sign away their land for strong drink. If you look at the record you will find what I say is true. All the country of America was got from the Indians for beads and rum or by cheating them."

- "The white man’s fire-wagons (automobiles) kill more people every year than all the Indians killed in a hundred years."

- "The white man thinks he is wise. The Indian thinks he is a fool. He kills all the buffalo and lets them rot on the ground. Then he plows up the grass, puff, the wind blows the ground away. No grass, no buffalo, no pony, no Indian, all starve. White man is a fool. Indian fool too for he gives the white man corn, potato, tobacco, tomato, all to make him rich. All the good the white man had got from the Indian. All the bad the Indian has got from the white man. Both fool."

- Looking at the big game country, the Chief was told that people paid over a million dollars each year to hunt deer. He said, "Much money for ticket. Indian kill just to get food, skins to make tipis, and moccasins and robes to keep warm. Never kill just for fun."

Final Days and Death

Chief Flying Hawk and his family faced many hardships. His son, Felix Flying Hawk, and grandson, David Flying Hawk, were treated unfairly by white men. His family and friends, like Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull, had been killed. He had to perform in shows to escape poverty on the reservation. He wore old clothes given to him. He said if he had what the government owed him, he could dress well and always have enough food. He was often hungry and couldn't afford medicine or a doctor when sick.

In March 1929, at age seventy-five, Flying Hawk made his last visit to The Wigwam. He had been traveling with the circus. The pony riding, war dances, and bad weather were affecting his health. The Wigwam offered him fresh air, good food, rest, and comfort. Chief Flying Hawk died at Pine Ridge, South Dakota, on December 24, 1931, at age 77. He had written that in the winter of 1930-31, his small group was saved from starvation only by donations from Gutzon Borglum and the American Red Cross. It was rumored that Chief Flying Hawk died from lack of food.