Sitting Bull facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sitting Bull

|

|

|---|---|

| Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake | |

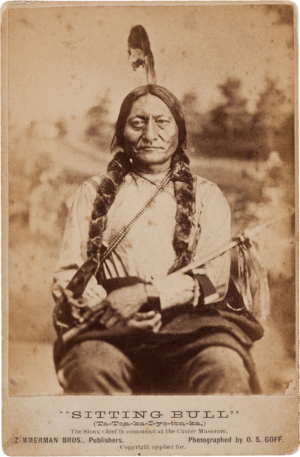

Sitting Bull, c. 1883

|

|

| Born |

Húŋkešni (Slow) or Ȟoká Psíče (Jumping Badger)

c. 1831 Grand River, Dakota Territory, U.S.

|

| Died | December 15, 1890 (aged 58–59) |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wound |

| Resting place | Mobridge, South Dakota, U.S. |

| Known for | Hunkpapa Lakota holy man and leader |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Military career | |

| Battles/wars | Battle of the Little Bighorn |

| Signature | |

Sitting Bull (born around 1831, died December 15, 1890) was a famous leader of the Hunkpapa Lakota tribe. He bravely led his people for many years against the policies of the United States government. Sitting Bull was killed during an attempt to arrest him. Authorities were worried he might join a spiritual movement called the Ghost Dance.

Before the famous Battle of the Little Bighorn, Sitting Bull had a special vision. He saw many soldiers falling upside down into the Lakota camp. His people believed this meant they would win a big victory. About three weeks later, the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne tribes defeated the 7th Cavalry led by Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer. This battle, on June 25, 1876, seemed to fulfill Sitting Bull's vision.

After this victory, the U.S. government sent many more soldiers. This forced many Lakota to give up. But Sitting Bull refused to surrender. In May 1877, he led his group north to Wood Mountain in Canada. He stayed there until 1881. Then, he and most of his group returned to the U.S. and surrendered.

Later, Sitting Bull worked as a performer in Buffalo Bill's Wild West show. He then went back to the Standing Rock Agency in South Dakota. Fears grew that he would support the Ghost Dance movement. So, the Indian Service ordered his arrest. During a struggle, Sitting Bull was shot and killed by police officers.

Contents

Early Life and Becoming a Warrior

Sitting Bull was born in what is now Dakota Territory between 1831 and 1837. At birth, he was named Ȟoká Psíče, which means "Jumping Badger." People also called him Húŋkešni or "Slow" because he was careful and unhurried.

When he was 14, he joined Lakota warriors, including his father, to take horses from the Crow tribe. He showed great bravery by riding forward and touching a Crow warrior without harming him. This act, called "counting coup," was a sign of courage. When he returned, his father held a feast and gave his own name, Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake, to his son. This name means "Buffalo Who Sits Down," but Americans called him "Sitting Bull." From then on, his father was known as Jumping Bull. Sitting Bull received an eagle feather, a warrior's horse, and a buffalo hide shield. These gifts marked his passage into manhood as a Lakota warrior.

During the Dakota War of 1862, the Lakota were not involved. However, the United States Army fought back against other Native American groups. In 1864, about 2,200 soldiers attacked a village. Sitting Bull, Gall, and Inkpaduta led the defense. The Lakota and Dakota were forced to leave, but fighting continued.

Later that year, Sitting Bull and about 100 Hunkpapa Lakota met a small group of soldiers. Sitting Bull led an attack and was shot in his left hip. The wound was not serious.

Protecting Their Land

From 1866 to 1868, Red Cloud, an Oglala Lakota leader, fought U.S. forces. He attacked forts to keep control of the Powder River Country in Montana. Sitting Bull supported Red Cloud. He led many war parties against forts and their allies. This conflict became known as Red Cloud's War.

By 1868, the U.S. government wanted peace. They agreed to Red Cloud's demands to leave some forts. Many Lakota leaders signed a peace agreement called the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868). But Sitting Bull refused. He told a missionary, "I wish all to know that I do not propose to sell any part of my country." He continued to attack forts in the upper Missouri area.

Some historians say Sitting Bull was made "Supreme Chief of the whole Sioux Nation" around this time. However, Lakota society was not set up with one main chief. Different groups and their elders made their own choices, including whether to go to war.

The Great Sioux War of 1876

Sitting Bull's group kept attacking settlers and forts in the late 1860s. In 1871, the Northern Pacific Railway tried to build a railroad through Hunkpapa lands. They faced strong resistance from the Lakota. The railway workers returned with soldiers, but Sitting Bull and the Hunkpapa attacked them again.

In 1874, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer led soldiers to explore the Black Hills for gold. Custer's announcement of gold caused a "gold rush." Many European Americans wanted to move into the Black Hills. This made tensions rise with the Lakota.

The U.S. government was pressured to open the Black Hills for mining. They tried to buy or lease the land, but failed. The 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie had promised to protect the Sioux's land. In November 1875, President Ulysses S. Grant ordered all Sioux groups outside the Great Sioux Reservation to move onto it. The government knew not everyone would obey. By February 1876, groups still living off the reservation were called "hostile." This allowed the military to chase them.

During 1868–1876, Sitting Bull became a very important Native American leader. Many traditional Lakota warriors moved to reservations and depended on the U.S. government for supplies. But Sitting Bull refused to depend on the U.S. government. He and his small group often lived alone on the Plains. When Native Americans felt threatened, many people from different Sioux groups and other tribes, like the Northern Cheyenne, joined Sitting Bull's camp. He became known for his "strong medicine" because he kept avoiding the European Americans.

In 1875, several tribes, including the Northern Cheyenne and Hunkpapa, gathered for a Sun Dance. Sitting Bull had an important vision during this ceremony. He saw that the Great Spirit had given their enemies to them to destroy.

After January 1, 1876, the U.S. Army began hunting down Native Americans living off the reservation. Many joined Sitting Bull's camp for safety. He encouraged this "unity camp" and sent scouts to invite more warriors. He also made sure his group shared supplies with newcomers.

Throughout the first half of 1876, Sitting Bull's camp grew larger and larger. It was estimated to have more than 10,000 people. Lt. Col. Custer found this huge camp on June 25, 1876. Sitting Bull did not fight directly in the battle. Instead, he acted as a spiritual leader. A week before the attack, he had performed the Sun Dance, where he fasted and sacrificed over 100 pieces of flesh from his arms.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn

On June 25, 1876, Custer's scouts found Sitting Bull's camp along the Little Bighorn River. The Lakota called it the Greasy Grass River.

Custer's 7th Cavalry troops attacked but quickly lost ground. Sitting Bull's followers, led by Crazy Horse, fought back. They defeated Custer's group and surrounded the other two groups of soldiers.

The Native Americans' celebration did not last long. The public was shocked and angry about Custer's defeat. The U.S. government sent thousands more soldiers to the area. Over the next year, the new American forces chased the Lakota, forcing many to surrender. Sitting Bull refused. In May 1877, he led his group across the border into Canada. He stayed there for four years.

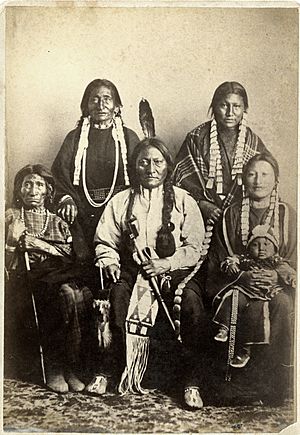

In Canada, Sitting Bull met James Morrow Walsh, a commander of the Mounties. Walsh explained that the Lakota were on British land and must follow British law. Walsh became a friend and supporter of Sitting Bull. Sitting Bull also met Crowfoot, a leader of the Blackfeet, who were old enemies of the Lakota. Sitting Bull wanted peace, and Crowfoot agreed. Sitting Bull was so impressed that he named one of his sons after Crowfoot.

Sitting Bull and his people stayed in Canada for four years. But it was hard to find enough food because the buffalo herds were smaller. Sitting Bull's presence also caused problems between the Canadian and U.S. governments.

Returning to the United States

Hunger eventually forced Sitting Bull and 186 of his family and followers to return to the United States. They surrendered on July 19, 1881. Sitting Bull's young son, Crow Foot, handed his rifle to Major David H. Brotherton. Sitting Bull said, "I wish it to be remembered that I was the last man of my tribe to surrender my rifle."

Two weeks later, Sitting Bull and his group were moved to Fort Yates, next to the Standing Rock Agency. This reservation is on the border of North and South Dakota. Sitting Bull and his group were kept separate from other Hunkpapa. U.S. Army officials worried he might cause trouble.

The military decided to send Sitting Bull and his group to Fort Randall as prisoners. They traveled by steamboat down the Missouri River to Fort Randall in South Dakota. They stayed there for 20 months. In May 1883, they were allowed to return north to the Standing Rock Agency.

Meeting Annie Oakley and the Wild West Show

In 1884, a show promoter asked if Sitting Bull could tour parts of Canada and the U.S. The show was called the "Sitting Bull Connection." During this tour, Sitting Bull met Annie Oakley in Minnesota. Oakley was a famous sharpshooter. Sitting Bull was so impressed with her skills that he paid for a photo of them together.

Sitting Bull greatly admired Oakley. He felt she was "gifted" with special abilities to shoot so accurately. Because of his respect, he symbolically "adopted" her as his daughter in 1884. He named her "Little Sure Shot," a name Oakley used throughout her career.

In 1885, Sitting Bull was allowed to leave the reservation again. He joined Buffalo Bill Cody's Buffalo Bill's Wild West show. He earned about $50 a week just for riding once around the arena. He was a very popular attraction. Some historians say he gave speeches about wanting education for young people and peace between the Sioux and white people. He earned money by signing autographs and taking pictures, but he often gave his money to people who were homeless or in need.

The Ghost Dance Movement

After the Wild West show, Sitting Bull returned to the Standing Rock Agency. There was growing tension between Sitting Bull and the Indian Agent, James McLaughlin. This was partly because of disagreements about dividing and selling parts of the Great Sioux Reservation.

During a time of harsh winters and long droughts, a spiritual movement called the Ghost Dance spread. It was started by a Paiute Indian named Wovoka. This movement taught that Native Americans should dance and chant for their deceased relatives to return and for the buffalo to come back. The dancers wore special shirts that they believed would stop bullets. When the movement reached Standing Rock, Sitting Bull allowed the dancers to gather at his camp. Even though he didn't seem to dance himself, he was seen as a key supporter. This caused alarm in nearby white settlements.

Death and Burial

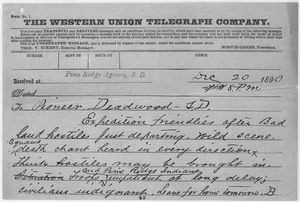

In 1890, James McLaughlin, the U.S. Indian agent at Fort Yates, worried that Sitting Bull might leave the reservation with the Ghost Dancers. So, he ordered the police to arrest him.

On December 15, around 5:30 a.m., 39 police officers and four volunteers surrounded Sitting Bull's house. They entered and told him he was under arrest. Sitting Bull and his wife tried to stall for time as the camp woke up. When police tried to force Sitting Bull onto a horse, a Lakota man named Catch-the-Bear shot one of the officers, Bull Head. In response, Bull Head shot Sitting Bull in the chest. Another officer, Red Tomahawk, also shot Sitting Bull, killing him. Sitting Bull died between 12 and 1 p.m.

A fight broke out, and several people died quickly. Six policemen were killed immediately, and two more died soon after. The police killed Sitting Bull and seven of his supporters.

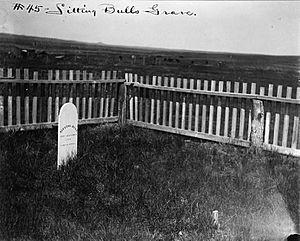

Burial Sites

Sitting Bull's body was taken to Fort Yates, North Dakota, where he was buried. A monument was later put up to mark his burial spot.

In 1953, members of Sitting Bull's Lakota family dug up what they believed were his remains. They moved them to be reburied near Mobridge, South Dakota, close to where he was born. A new monument was built there.

Legacy

After Sitting Bull's death, his cabin was moved to Chicago. It was used as an exhibit at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition.

On September 14, 1989, the U.S. Postal Service released a postage stamp featuring Sitting Bull.

On March 6, 1996, Standing Rock College was renamed Sitting Bull College in his honor. This college is on Sitting Bull's home of Standing Rock.

In 2010, scientists announced they planned to study Sitting Bull's DNA using a hair sample. In 2021, this research confirmed that Lakota writer Ernie LaPointe and his sisters are Sitting Bull's great-grandchildren.

See also

In Spanish: Toro Sentado para niños

In Spanish: Toro Sentado para niños

- Crazy Horse

- Black Elk

- Henry Mabb

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |