North-West Mounted Police facts for kids

Quick facts for kids North-West Mounted PoliceRoyal Northwest Mounted Police |

|

|---|---|

| Abbreviation | NWMP, RNWMP |

| Motto | Maintien le droit "To Maintain the Right" |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | May 23, 1873 |

| Dissolved | 1920 |

| Superseding agency | Royal Canadian Mounted Police |

| Legal personality | Government agency |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Federal agency (Operations jurisdiction) |

Canada |

| Operations jurisdiction | North-West Territories, Canada |

| Legal jurisdiction | As per operations jurisdiction |

| Governing body | Government of Canada |

| General nature | |

The North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) was a special police force in Canada. It was created in 1873 to keep peace in the new North-West Territories (NWT). This huge area became part of Canada after being bought from the Hudson's Bay Company in 1870. The NWMP was needed because of growing lawlessness and worries about the United States getting involved.

The NWMP was like a mix of a military and police force. It was designed to be small and quick to move. This helped avoid problems with the United States and First Nations groups. Their bright red coats looked like British and Canadian military uniforms. This showed they were a strong, official presence.

Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald created the NWMP. He wanted them to "preserve peace and prevent crime" in the NWT. He worried that American traders causing trouble, like the Cypress Hills Massacre, could lead to the U.S. military stepping in. Macdonald feared the U.S. might then take over the NWT.

In 1874, the NWMP made a long, difficult journey of almost 1,450 km (900 mi). This trip, known as the March West, showed their toughness. Over the next years, they built many forts and posts. They helped bring Canadian law to the vast region. Life for the NWMP on the prairies was often very basic.

By 1896, there were plans to end the NWMP. But then, gold was found in the Klondike. The NWMP was sent there to protect Canada's land and manage the many gold seekers. In 1904, King Edward VII added "Royal" to their name. This was to honor their service, especially during the Second Boer War. So, they became the Royal North-West Mounted Police (RNWMP).

Many RNWMP members joined the military during the First World War. After the war, the government worried about unrest. In 1920, the RNWMP joined with another police force, the Dominion Police. Together, they formed the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP).

History of the NWMP

Why Was the NWMP Formed?

The NWMP was created because Canada was growing. In the 1870s, Canada expanded into the North-West Territories. Canada had formed in 1867. But the huge lands to the north-west, called Rupert's Land, were still run by the Hudson's Bay Company.

The Canadian government wanted to expand west. They worried the United States might try to take the region. So, Canada bought these lands from the Hudson's Bay Company in 1870. This added a massive amount of territory to Canada.

The North-West Territories were very empty. Only about 150,000 First Nations and Inuit people lived there. There were also about 12,000 Métis people in the Red River valley. The southern part of what is now Alberta was home to the Blackfoot Confederacy. These First Nations hunted bison.

American traders were selling alcohol to First Nations people. This caused problems and violence. There was no formal government or police in the area. People worried about lawlessness. In 1869, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald planned a 200-person mounted police force. He thought it would help settle the region and be cheaper than soldiers.

How the NWMP Began (1873–1874)

Starting the Force

On May 23, 1873, the Canadian Parliament approved the new police force. It was called the Mounted Police Act. Macdonald wanted a force to watch the border from Manitoba to the Rocky Mountains. He was inspired by the Royal Irish Constabulary. This force combined military and police duties.

In June 1873, about 30 Assiniboine First Nation members were killed. This event, known as the Cypress Hills Massacre, caused a big outcry. Macdonald quickly formed the NWMP. He planned to send them west the next year.

The government changed, and Alexander Mackenzie became Prime Minister. He was also worried about the violence and illegal trade. He decided to send the new mounted police to the west. Another 150 men were hired in eastern Canada. They traveled by train through the U.S. to meet the first group at Fort Dufferin.

The March West

The NWMP's journey onto the plains in 1874 was called the "March West." Colonel George Arthur French, the force's leader, was told to go west from Fort Dufferin. Their goal was to deal with problems near Fort Whoop-Up. Then, they would set up police posts across the territories.

The expedition left Fort Dufferin on July 8, 1874. There were 275 police, 310 horses, and 143 oxen. They also had 187 carts and wagons. The line of travelers stretched for 2.4 km (1.5 mi). They carried two large guns and two mortars for protection.

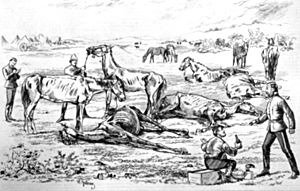

The journey was slow and very hard. The police had no water bottles, and food ran out. Their horses started to die as the weather got worse. On September 10, they arrived where they thought Fort Whoop-Up was. But the fort was actually 120 km (75 mi) away.

French had to change plans. He traveled south to the U.S. border for supplies. More horses died from cold and hunger. Many men were barefoot and in rags when they arrived. They had traveled almost 1,450 km (900 mi).

After getting supplies, French went back east. Assistant Commissioner James Macleod went to Fort Whoop-Up with 150 men. When they arrived on October 9, the traders had already left. The police built Fort Macleod nearby. The March West was poorly planned, but it became a famous story of bravery.

Early Years of the NWMP (1874–1895)

Working with First Nations

When the mounted police arrived, the illegal trade around Fort Macleod stopped. The Blackfoot people welcomed the police. Their leader, Crowfoot, chose to work with them. The police built more forts across the territories.

The police applied Canadian law to First Nations. But they also supported First Nations when dealing with white ranchers. They built good relationships with First Nations leaders. This led to less violence than in the United States. First Nations people liked that the NWMP removed the American traders. Crowfoot said in 1877, "The Mounted Police protected us as the feathers of the bird protect it from the frosts of winter."

In 1876, the buffalo herds moved away. This caused hunger for the Blackfoot. Crowfoot decided his people needed to work with the mounted police. In 1877, formal talks began between Canada and the Blackfoot. Macleod represented Queen Victoria. The Treaty 7 was signed. It set aside land for the Blackfoot.

Around the same time, the police managed the Sitting Bull incident. In 1876, Sitting Bull, a Sioux leader, came to Canada. He sought safety from the U.S. military. By summer, about 5,600 Sioux had crossed the border. The mounted police helped with talks. Sitting Bull refused to go back south. The police had to watch over the Sioux community. Hunger eventually forced most Sioux to return to the U.S. Sitting Bull surrendered in 1881.

The police first focused on stopping illegal alcohol. They believed it caused violence among First Nations. Later, they also worked to stop horse theft. This was common among First Nations. The police worried that horse theft from the U.S. could cause military problems.

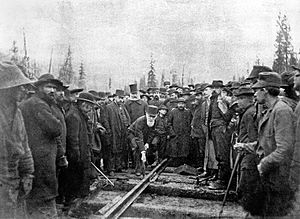

Building the Canadian Pacific Railway

In 1881, Canada began building the Canadian Pacific Railway. This railway would connect eastern Canada to British Columbia. It was meant to open up the western territories for settlement. The mounted police moved their main office to Regina. Regina was a new city built along the railway. The force grew to 500 men in 1882.

The police helped with many railway tasks. They guarded construction teams in the Rocky Mountains. They enforced laws and watched over workers. They helped solve problems when workers were not paid. They also supported the railway company. When railway workers went on strike in 1883, the police guarded trains. They even drove locomotives sometimes.

The railway caused new problems with First Nations. The government wanted to move First Nations to reserves north of the railway. First Nations were unhappy about the railway on their lands. They stole horses and stopped construction. The police made arrests. By 1883, hunger forced First Nations to move north of the railway line.

The North-West Rebellion

In 1885, the North-West Rebellion started. Louis Riel and his Métis followers wanted to form their own government. They hoped to get support from the Cree First Nation. The police had worried about trouble for months. Commissioner Acheson Irvine gathered police in Regina.

When the rebellion began in Batoche in March, Irvine went to Prince Albert. He guarded it with 90 police. Superintendent Leif Crozier led police and volunteers to Fort Carlton. They fought rebels at Duck Lake and lost. Some Cree leaders, like Poundmaker and Big Bear, joined the Métis. The police left most of their posts. Inspector Francis Dickens had to escape Fort Pitt by boat.

More than 5,000 soldiers came west by railway. Major-General Frederick Dobson Middleton led them. Middleton's forces attacked the rebels. They won the Battle of Batoche, and Riel surrendered. Riel was imprisoned by the mounted police in Regina. He was tried and executed.

Middleton criticized the mounted police. He said they stayed in Prince Albert and did not help enough. He suggested getting rid of the force. Irvine resigned and was replaced by Lawrence Herchmer. Crozier also resigned.

Life on the Prairies

After the rebellion, more white settlers came to the North-West. By 1885, they were the majority. The mounted police grew to 1,000 men. This was to handle the growing population and prevent future uprisings. Crime was low at first. The police were informal, focusing on the spirit of the law.

Cattle ranchers moved into the territories. The police had close ties to ranch owners. Illegal squatting by poorer settlers became a problem. The police had to evict them. This was an unpopular job. The police also helped with cattle issues along the border.

Horse theft by white thieves increased. Commissioner Herchmer started a system of police patrols. They visited almost every farm and ranch. They got to know people and gathered information. They also helped distribute aid, gave medical help, and delivered mail. Police traveled 2.4 million km (1.5 million mi) each year on horseback. This system greatly reduced rural crime.

A new "pass system" was introduced for First Nations. It meant a First Nations person needed a pass to leave their reserve. The police knew this was illegal. It went against Treaty 7, which promised free movement. But they enforced it for years. The police also used First Nations people as special constables. These constables were scouts and trackers.

Enforcing alcohol prohibition caused problems. Most settlers did not like these laws. Public anger towards the police grew. In 1892, new laws allowed licensed bars. This removed most of the police's job in enforcing alcohol laws.

Later Years (1895–1914)

Growing Cities

By the late 1800s, Canada changed a lot. Many immigrants arrived, especially from eastern Europe. Cities grew, and industries expanded. The mounted police struggled to keep up. Crime cases increased. In 1900, there were fewer than 1,000 cases. Four years later, there were over 4,000.

The police were asked to help local governments in many ways. This included public health, giving aid, and fighting fires. They also helped build new railways. Police officers acted as judges and helped solve problems between companies and workers.

Worker Strikes

Workers in new industries often had poor conditions. They had few rights. Workers who left their jobs could be arrested. The number of worker strikes grew. Sometimes, armed government help was needed. The mounted police were often used because they were cheaper than soldiers.

The police were called to manage strikes many times. For example, in Lethbridge, miners went on strike in 1894. Ten police were sent to keep order. They also tried to help solve the dispute. In 1906, 82 police and 11 special constables were sent there again. They gathered information on union leaders. The police kept order and helped non-striking workers pass picket lines.

Historians have different views on whether the police were neutral. They agree that the police's job became harder as unions grew. The police did not like some strike leaders. But they also felt some sympathy for workers.

The Klondike Gold Rush

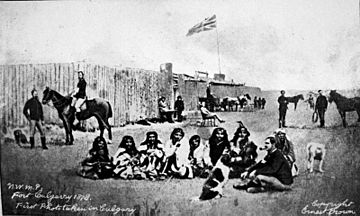

Before the 1890s, Canada had no police in the far north-west. In 1894, gold mining grew. People wanted the government to step in. The mounted police surveyed the Yukon River. They collected customs duties. People worried the United States might try to take the rich gold region. So, a twenty-man police team was sent to Forty Mile in 1895.

In 1896, huge amounts of gold were found in the Klondike valley. News spread, and about 100,000 people rushed there. Most had no mining experience. Many traveled over hard mountain routes. A large NWMP group was sent to the Klondike. By 1898, there were 288 men. This was about a third of the whole force.

The borders in the region were disputed with the U.S. The police were told to show Canada's control. They set up posts at the Yukon borders and mountain passes. They checked for illegal weapons and stopped criminals. They also helped guide migrants and settled disputes.

The police set up their main office in Dawson City. They patrolled the Yukon Territory. They had thirty-three posts. Police also handled fire safety, hunting, mail, and mining registration. The police kept crime low in the region. The Klondike Gold Rush became famous worldwide. Dawson City was orderly, unlike the chaotic Skagway, Alaska. In 1897, NWMP riders in their red uniforms marched in London. This made the "Mounties" famous.

The Second Boer War

When the Second Boer War started in 1899, many police wanted to fight. They felt loyal to the British Empire. Commissioner Herchmer had wanted to send men to Sudan earlier. Canada offered soldiers to Britain. The government looked to the mounted police for experienced mounted soldiers. Police members were given time off to serve. This reduced the police force in Canada to 682 men by 1900.

Herchmer led 144 mounted police volunteers. They formed almost half of the new 2nd Battalion of the Canadian Mounted Rifles. Many other volunteers were also former police. Herchmer was later removed from command. Prime Minister Macdonald then fired him from the police. Aylesworth Perry became the new Commissioner.

The mounted police also influenced other units. Lord Strathcona created a mounted infantry unit. Thirty-three police joined it. The Strathconas wore the police's Stetson hat. The South African Constabulary was also created. It was like the mounted police. Forty-two police joined it. Sergeant Arthur Herbert Lindsay Richardson won the Victoria Cross for bravery. In 1904, the King renamed the force the Royal Northwest Mounted Police (RNWMP). This honored their service in the war.

Expanding into the North

After the Klondike Gold Rush, the mounted police kept expanding north. They set up posts across the far north. This was hard because of the cold and lack of supplies. New railway lines helped bring supplies. The police opened temporary posts around York Factory in 1912.

First Nations in the north had met Europeans before. There was little conflict with the police. But First Nations often blamed the police for government policies. The police got along better with the Inuit. They often used informal justice for Inuit crimes. First Nations and Inuit people helped the police. They drove dog sleds and cooked for patrols.

Final Years (1914–1920)

First World War Duties

When Canada entered the First World War in 1914, the government worried about national security. They feared immigrants or U.S. citizens might cause trouble. The federal Dominion Police were in charge of this. But they had few resources. So, they gave many duties to local police, including the mounted police.

The mounted police first focused on immigrants and border security. They investigated rumors of plots. They used secret agents and informants. Tensions grew between temperance groups and soldiers over alcohol laws. In October 1916, a crowd attacked the police barracks in Calgary. The building was destroyed, and officers were hurt.

The police were stretched thin. Commissioner Perry said they were "overstretched." The Alberta Provincial Police and Saskatchewan Provincial Police were created. This allowed the closure of over 80 mounted police posts. Perry argued the force had finished its original work. He wanted the police to support the war in Europe. In May 1918, 738 mounted police were sent overseas. Another 186 went to Siberia to help British forces. By December, only 303 mounted police were left in Canada.

Worries About Unrest

During the war, Canada introduced conscription. There were worker shortages and calls for social change. In late 1918, the government worried about unrest. They feared the new Russian government might be causing strikes in Canada. Prime Minister Robert Borden created a Public Safety Branch.

Commissioner Perry suggested three options for the mounted police's future. They could join the military, only police the far north, or have a wider role across Canada. Perry liked the third option. Arthur Meighen, the acting Minister for Justice, suggested merging the mounted police and the Dominion Police.

In December 1918, Borden reorganized Canada's security. The mounted police would handle the western half of the country. The Dominion Police would handle the eastern side. The mounted force was to have 1,200 men. Police in Europe and Siberia were called back. The police began to use secret agents. They looked for "Bolshevik tendencies" among immigrants. They also used new laws to deport immigrants without trial. The police found no major plots.

Joining Forces

The government was still worried about unrest. In May 1919, the Winnipeg General Strike started. Ministers feared a revolution. The mounted police were sent to keep order. 245 mounted police went to the city. They had four machine guns on trucks.

On June 21, known as Bloody Saturday, veterans marched to support the strikers. The police were called to break up the march. Protesters began to riot. The police charged twice. They felt they were losing control and fired into the crowd. One man was killed, and others were hurt. The marchers fled, and the strike ended.

The events in Winnipeg showed that Canada's security was not well organized. There was a clear need for one strong federal police force. Commissioner Perry suggested merging the Dominion Police into the mounted police. He argued the mounted police were larger, more experienced, and had high public respect.

In November 1919, Prime Minister Borden changed the laws. The RNWMP and the Dominion Police joined to form the RCMP. The new force was in charge of federal law enforcement and national security across Canada. Perry became its first commissioner. This change happened on February 1, 1920. It marked the end of the old force.

How the NWMP Worked

Structure of the Force

When the NWMP started in 1873, it had ranks like inspectors and constables. The whole force was led by a commissioner. This was like the Royal Irish Constabulary. In 1878, the ranks changed to superintendents, inspectors, sergeants, corporals, and constables. Officers were often called by army titles, like major or captain.

The NWMP had five commissioners:

- George French (1873–1876)

- James Macleod (1876–1880)

- Acheson Irvine (1880–1886)

- Lawrence Herchmer (1886–1900)

- Aylesworth Perry (1900–1920)

At first, the force reported to the prime minister. Later, it reported to the Secretary of State. The police had informal rules at first. They used British military rules. This made things a bit messy. In 1889, a longer "Regulations and Orders" book was made. This helped make the force more organized.

The force was split into divisions. Each was led by a superintendent. The main office moved to Regina in 1888. Many posts were linked by telegraph and later by telephone. They used codes for secret messages. The police did not have their own prisons. People sentenced to jail went to the Manitoba Penitentiary.

A special role called comptroller was created in 1880. This person managed money and buying supplies. Frederick D. White held this job for most of the force's history. He helped get support from the government in Ottawa.

Officers and Recruits

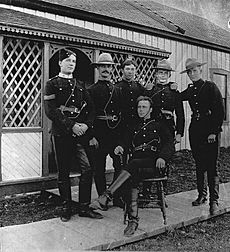

The NWMP was led by a small group of officers. In the early years, there were about 25 officers. They were usually from middle or upper-class families. Most were Canadian-born. They were chosen based on military experience or police service.

Officers were part of Canada's social elite. They saw themselves as similar to regular military officers. They were also Justices of Peace. This gave them power to judge civilian cases. They could also punish their own police members. Officers were paid well for the time. But they had to buy uniforms and attend social events. Most found it hard to support a family on their police pay alone.

The first recruits in 1873 had varied backgrounds. Many had military experience. Less than half finished their service. Later, more care was taken in hiring. At first, most police were Canadian. But by the 1880s, over half were British-born. By 1914, almost 80 percent of the force was born in Britain.

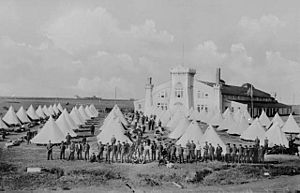

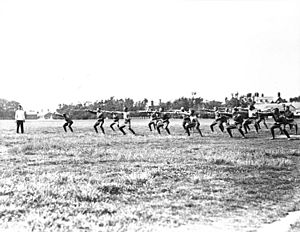

Recruits signed up for three or five years. Training was informal at first. In 1885, a training depot was built in Regina. This made training more structured. Efforts were made to get better recruits. They also tried to stop people from leaving early.

Constables were paid 75 cents a day in 1873. They were promised land. But pay was cut to 50 cents a day in 1878. Land grants stopped. A constable could earn over $300 a year. This was similar to a school teacher's pay. By the early 1900s, police pay was low compared to other jobs. It slowly increased to $1.75 a day by 1919. A pension plan was started in 1889.

Early police lived in "forts." These were simple log buildings with sod roofs. Conditions were basic. They used wood stoves for heat and light. Constables slept on wooden boards. In the early 1880s, conditions were so bad that police at Fort Macleod demanded improvements.

Conditions slowly got better. Later barracks were built better. They had modern technology and iron beds. Larger barracks had canteens and reading rooms. But life on the prairies was still hard. Mosquitoes and lice were common. In the far north, police lived in very basic and dangerous conditions. Small shelters were built for patrols. But some, like the "Lost Patrol" in 1910–11, still died from the cold.

| Other ranks | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1870s | Chief Constable | Staff Constable | Constable | Sub-Constable | |

| 1880s–1890s | Sergeant major | Staff sergeant | Sergeant | Corporal | Constable |

| 1900s | Sergeant major | Staff sergeant | Sergeant | Corporal | Constable |

Uniform and Badge

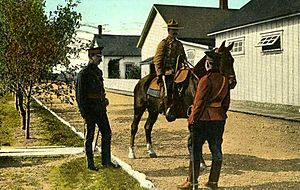

The first police recruits in 1873 wore scarlet jackets. They had brown belts, white helmets, and grey pants. The grey pants soon changed to blue with a yellow stripe. These early uniforms were simple. Officers and regular police wore similar clothes.

In 1876, uniforms became more fancy. Officers had uniforms like the 13th Hussars. Non-commissioned officers had gold braid. Winter uniforms were grey overcoats with fur caps. Police preferred warmer buffalo coats. In 1886, simpler uniforms were introduced. Dark-blue everyday uniforms were also added.

There was always a balance between smart uniforms and practical ones. The white helmets and tight tunics were not good for work on the plains. So, "prairie dress" became popular. This included a buckskin jacket, oilskins for rain, and leather leggings. A wide-brimmed felt hat, like the Stetson, became common. By 1900, many police wore a red jacket like the prairie tunic. This, with the Stetson, became famous.

In the far north, police wore special cold-weather clothes. They used deer-skin parkas and fur hats. In extreme cold, they wore local Inuit clothing. Police sent to Siberia wore army khaki uniforms.

The force's badge appeared around 1876. It showed a buffalo head, maple leaves, and a crown. The motto was "Maintien le Droit" (To Maintain the Right). This motto was changed slightly in 1915. The famous phrase "The Mountie always gets his man" is not official. It came from Hollywood and newspapers.

Equipment of the NWMP

Weapons and Gear

The mounted police were an armed force. They were first given Snider-Enfield Carbine Mark III rifles. But these were single-shot guns. They were not as good as the repeating rifles used by First Nations in the U.S. In 1878, they got Winchester Model 1876 repeating rifles. These guns were delicate. In 1895, they started using Lee-Metford Magazine Carbines. But these did not work well. In 1902, the Lee-Enfield Magazine Rifle Mark I became the standard rifle. The police had little ammunition. So, they did not practice much, and their shooting skills were often poor.

Police also carried revolvers. They used different types over the years. The Colt New Service Revolver became standard in 1904. Smaller revolvers were bought for undercover officers.

In 1873, the police brought 25 lances. These were meant to impress the Blackfoot. They also used swords. Officers had fancy sabres. Non-commissioned officers carried different swords. Some constables also carried swords. In 1880, they debated if swords were still useful. By 1882, non-commissioned officers were allowed to carry sabres.

The force also had artillery. This was mainly to deter attacks from First Nations. They had 9-pounder field guns and mortars. Later, they got 7-pounder field guns. Machine guns arrived in 1894. These were .303 calibre Maxim guns. Some guns were used in the Métis rebellion. One 9-pounder gun was used in 1897 to kill a Cree fugitive.

Horses and Vehicles

The mounted police started with 310 horses in 1873. Many died on the March West. For years, there were not enough horses. Horses became very important, especially for patrols. By the 1880s, horses were well cared for. A large riding school was built in Regina in 1886. At their peak, the force owned about 800 horses. They bought 100 new horses each year. They used Western saddles, which were more comfortable.

The police also used pack ponies and mules. Oxen were used for pulling wagons early on. In the far north, they used dog-sled teams and canoes.

In the early 1900s, cars started to replace horses. Horses were still used for crowd control. The force bought its first car in 1915. They started using cars and motorcycles for border patrols. By 1920, they had 33 cars and trucks, and 28 motorcycles. There was a plan to use aircraft, but it was rejected.

The police also bought boats for coastal and river work. They had sailing vessels and steamers. These were used on lakes and rivers. By 1919, they had several motor vessels patrolling the far north and west coast.

Suppliers

At first, most equipment and weapons were imported. Canada did not have much industry. Saddles and wagons came from the U.S. Uniforms were made locally. After 1887, there was pressure to use Canadian suppliers. Food was bought from large trading companies. Later, it came from smaller local firms. The police became important customers. Supplies had to be bought from companies that supported the government. Guns always had to be imported. Ammunition was often bought from abroad because Canadian-made bullets were not good enough.

Cultural Legacy

The NWMP in Stories and Movies

The NWMP's early fame came from newspaper stories and books by retired officers. At first, some newspapers criticized them. But soon, a heroic and romantic image grew. This was helped by events like the Musical Ride, first performed in 1887. It showed cavalry charges and lance displays.

The NWMP first appeared in fiction in 1885. They became popular characters. Over 150 novels about the force were published between 1890 and 1940. Magazine articles and children's books also featured them. Writers like Gilbert Parker and James Curwood were very popular. These stories often had a brave, honest policeman. He would chase a suspect across the wilderness. The stories focused on justice and fair play.

British writers often saw the police as upper-class soldiers serving the British Empire. Canadian novels also had this idea. But they also showed the force as protecting moral order. American authors often used Western story plots. But they used Canadian characters and settings.

In the 1930s and 1940s, the force was in many radio shows and movies. Radio series like Sergeant Preston of the Yukon showed the police as heroes. This show later became a TV series. Over 250 films were made about the force. This included the musical Rose Marie. Their popularity faded in the 1970s. But their image still influenced later TV shows like Due South.

The phrase "the Mountie always gets his man" was never official. But it became very famous.

Studying the NWMP's History

The historical records of the NWMP were combined with the RCMP's in 1920. But early records from 1873 to 1885 were destroyed in a fire. For most of the 1900s, the RCMP kept most records secret. Only certain researchers could see them. So, early historians often wrote stories that matched the popular image of the police. These histories were often "romantic and heroic."

This traditional view of the NWMP shaped how people saw the RCMP. The RCMP, though formed in 1920, traces its history back to 1873. In 1973, the RCMP celebrated its 100th anniversary. There were many events and books. The RCMP used these celebrations to show the NWMP's role in creating a modern Canada.

In the early 1970s, historians started to look at the force's history in new ways. They looked at social issues, race, and class. This led to more critical histories. In the 1980s, legal cases made more old records public. This led to new research on the police's role in wars and worker disputes.

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |