Winnipeg General Strike facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Winnipeg general strike |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Canadian Labour Revolt | |||

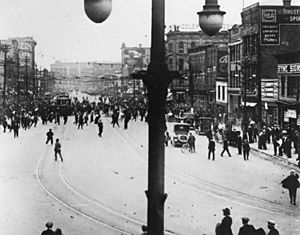

Crowd gathered outside old City Hall during the Winnipeg general strike, June 21, 1919

|

|||

| Date | May 15 – June 26, 1919 | ||

| Location | |||

| Methods | Strikes, protests, demonstrations | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 2 | ||

| Injuries | 30 | ||

| Arrested | 80 | ||

The Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 was one of the most important strikes in Canadian history. For six weeks, from May 15 to June 26, over 30,000 workers stopped most businesses and services in Winnipeg, Manitoba. At that time, Winnipeg was Canada's third largest city.

The strike ended with arrests and some violence. The workers did not get everything they wanted right away. However, in the long run, the strike helped make unions stronger. It also led to new political ideas in Canada, especially for social change.

Contents

Why the Strike Happened

Many things led to the strike. Most of them were about unfair conditions and hard lives for workers in the city. Workers had low pay, rising prices, unstable jobs, and poor living conditions. Immigrants often faced unfair treatment. People were also angry about the huge profits employers made during World War I.

Soldiers returning from the war wanted better social conditions and opportunities. Many workers did not have unions to represent them. However, they hoped that unions could help them get more financial security.

Many workers were also interested in socialist ideas. These ideas were shared by local reformers and activists. After the Russian Revolution in 1917, these ideas became even more popular, especially among immigrants from Eastern Europe.

In March 1919, a meeting of western labour leaders in Calgary made several big decisions. They supported a five-day work week and a six-hour workday. They also wanted to create a new union group called the One Big Union (OBU). This group aimed to unite workers from all jobs and industries into one organization. The OBU was not officially formed until June 1919, so it did not start the general strike. But the idea of "one big union" added to the feeling of unrest. Similar problems existed in other parts of Canada and around the world after World War I. But in Winnipeg, everything came together in an explosive way.

The main reason for the strike was about workers in the metal and building trades. These workers wanted to negotiate contracts through their trade councils. When they could not agree on contracts by the end of April, they went on strike. The building trades started on May 1, and the metal trades on May 2.

Soon after, the Winnipeg Trades and Labour Council discussed the situation. This council was the main group for all unions in the city. The Labour Council decided to ask its 12,000 members to vote on a general strike. A similar tactic had worked for city workers in 1918.

On May 13, the results of the vote were announced. There was huge support for a general strike: 8,667 votes for, and only 645 against. Ernest Robinson, the Labour Council's secretary, said that "every organization but one has voted in favour of the general strike." He also stated that "all public utilities will be tied-up to make sure collective bargaining happens."

A Strike Committee was formed, with members chosen by the city's unions. The leaders included both moderate union members, like James Winning, and socialists, like R.B. Russell.

The 1919 General Strike

How the Strike Was Organized

At 11:00 a.m. on Thursday, May 15, 1919, almost all workers in Winnipeg went on strike. About 30,000 public and private sector workers left their jobs. Many normal city activities suddenly stopped.

The Strike Committee asked the police force, who had voted for the strike, to stay on duty. Workers at the city waterworks also stayed to provide water service at a lower pressure. Union membership had grown a lot in the spring of 1919. But most people who joined the general strike were not union members. For example, the first to leave work were the telephone operators, called "hello girls." They were not union members at the time. Also, on the first day, major groups of returned soldiers announced their support. They remained active throughout the six weeks of the strike.

In the early days, the mood was almost like a party. People strongly believed they would win. Strikers gathered in city parks to hear speakers talk about the strike's progress. They also discussed many social reform issues of the time. To keep everyone informed, the Strike Committee published a daily Strike Bulletin. This newspaper told strikers to stay peaceful and idle. It said: "The only thing the workers have to do to win this strike is to do nothing. Just eat, sleep, play, love, laugh, and look at the sun... Our fight consists of doing no fighting."

Women leaders were very important in bringing strikers together. Experienced organizers like Helen "Ma" Armstrong, one of two women on the Strike Committee, encouraged young working women to join. She often spoke on street corners and at public meetings. The Women's Labour League raised money to help women workers pay rent. They also set up a kitchen that served hundreds of meals daily. On June 12, a "ladies day" was held at Victoria Park. Women sat in special seats to cheer a speech by J.S. Woodsworth. He spoke about women's rights and equality. Edith Hancox, a rising working-class activist, was the only woman reported as a speaker at the huge outdoor gatherings at Victoria Park.

The Strike Committee, city council, and local businesses agreed to continue milk and bread deliveries. To show that delivery people were not working against the strike, a small poster was printed. It was displayed on their wagons and read: "PERMITTED BY AUTHORITY OF STRIKE COMMITTEE." Although management suggested these cards, they were also seen as proof that the Strike Committee was trying to take control of the city.

Who Opposed the Strike

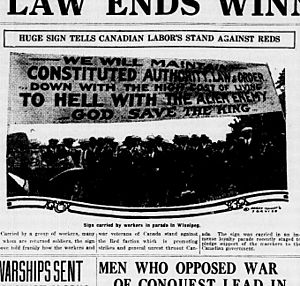

Winnipeg was divided by class. A group of local businessmen and professionals led the opposition to the strike. They called themselves the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand. From their office, they told employers not to give in to the strikers. They also tried to create anger against "alien" immigrants, claiming they were the main strike leaders. They pressured the government to act against the strike. They published a newspaper, The Winnipeg Citizen. It claimed that "the so-called general strike is in reality revolution – or a daring attempt to overthrow the present industrial and governmental system."

At the end of the first week, two federal government ministers came to Winnipeg. They were Arthur Meighen, the acting Minister of Justice, and Gideon Robertson, the Minister of Labour. They refused to meet with the Strike Committee. Instead, they talked with the Citizens’ Committee, who greatly influenced their views. Meighen said the strike was "a cover for something much deeper—an effort to 'overturn' the proper authority." Robertson told Ottawa that "the reason behind this strike was clearly to overthrow Constitutional Government." They warned striking postal workers, who worked for the federal government, to return to work or lose their jobs. They also allowed the local government to use the armed forces and the Royal Northwest Mounted Police if needed.

In early June, the federal government changed the Immigration Act. This was done on the advice of A.J. Andrews, a leader of the Citizens' Committee. The change allowed British citizens not born in Canada to be deported without a trial if they were accused of rebellious activity.

The city government also took action. Many veterans were marching in the streets to support the strike. So, on June 5, Mayor Charles F. Gray banned public demonstrations. On June 9, the city also fired almost all police officers. This was because they refused to sign a promise not to join a union or take part in a sympathetic strike. With help from the Citizens’ Committee, the city police were replaced. New special constables, who were untrained but paid more, patrolled the streets with clubs. Within hours, one of these special constables, Frederick Coppins, charged into a group of strikers. He was pulled off his horse and badly beaten. This led to claims that "enemy ruffians" attacked him.

The local newspapers, the Winnipeg Free Press and Winnipeg Tribune, lost most of their staff due to the strike. But once they started publishing again, they strongly opposed the strike. The Winnipeg Free Press called the strikers "bohunks," "aliens," and "anarchists." It also ran cartoons showing radicals throwing bombs. These anti-strike views affected some Winnipeg residents and made the situation more tense.

In the middle of June, there was a plan to offer a new way of collective bargaining to the Metal Trades Council. But any attempts to find a compromise ended when several strike leaders were arrested. They were charged with planning rebellious acts. In the early morning hours of June 17, the RNWMP arrested several important strike leaders. These included George Armstrong, Roger Bray, Abraham Heaps, William Ivens, R.B. Russell, and John Queen. Also, William Arthur Pritchard, a union organizer from Vancouver, was arrested in Calgary while returning from Winnipeg. R. J. Johns, from Winnipeg, was in Montreal and not arrested at this time. Except for Armstrong, who was Canadian-born, all were British immigrants. Several foreign-born socialists were also arrested, as was Oscar Schoppelrei, an American-born Canadian war veteran of German background.

What Happened on Bloody Saturday

The most intense part of the strike happened a few days later, on Saturday, June 21. This day became known as Bloody Saturday. To protest the arrest of the strike leaders, returned soldiers announced a "silent parade" on Main Street for Saturday afternoon. Thousands of people gathered in the streets around City Hall.

When the soldiers refused to cancel the demonstration, Mayor Gray asked the RNWMP for help. The Mounties rode into the crowds on horseback, using clubs to try and break up the gathering. A streetcar driven by a strikebreaker tried to go south on Main Street. But it was stopped, tipped off its tracks, and briefly set on fire.

After the Mayor read the Riot Act, the Mounties attacked again. This time, they fired their .45 revolvers three separate times. About 120 shots were fired. One man, Mike Sokolowski, was killed instantly. Another, Steve Szczerbanowicz, died later from his injuries. Hospitals reported about 30 people hurt, mostly from police gunfire. Others were helped by friends and family. As the crowds were chased into side streets and broken up, about 80 people were arrested by the "specials" and military patrols that took over the downtown area.

When the Strike Bulletin published its story of Bloody Saturday, the editors, J.S. Woodsworth and Fred J. Dixon, were arrested. They were charged with publishing rebellious writings. They had printed articles with titles like “Kaiserism in Canada” and “The British Way.” The charges against Woodsworth included his quote from the Bible: "Woe unto them that decree unrighteous decrees." The newspaper was then stopped from publishing more issues.

These events made the Strike Committee lose confidence. On June 25, they announced the strike would end at 11:00 a.m. the next day. After six weeks, workers slowly returned to their jobs. But many were put on a blacklist or punished for taking part in the strike.

Role in the Labour Revolt

In May and June 1919, general strikes also happened in about thirty other cities. These ranged from Amherst, Nova Scotia, to Victoria, British Columbia. Some of these strikes were about local problems. Some were to show support for Winnipeg. Others were for both reasons.

What Happened After the Strike

Trials and Outcomes

Eight of the strike leaders were put on trial. They were accused of planning rebellious acts. The evidence against them focused more on their socialist ideas than on their actions. These ideas were seen as the main cause of the unrest that led to the general strike. The federal government paid for the prosecution. The lawyers for the prosecution were Andrews and other "legal gentlemen" who were active in the Citizens’ Committee during the strike.

Seven of the accused (Armstrong, Bray, Ivens, Johns, Pritchard, Russell, and Queen) were found guilty. The juries for these trials were mostly from rural areas. Most were sentenced to one year in prison. Russell was sentenced to two years, and Bray, who was found guilty of a lesser charge, got six months. (John Farnell, who took over leadership of the pro-strike soldiers after Bray's arrest, was sentenced to nine months. He was released three months early because his wife was ill.)

Heaps defended himself and was found not guilty of all charges. Dixon, who was accused of rebellious writing, strongly defended the right to free speech. After 40 hours of thinking, the jury, which was mostly from the city, found him not guilty. Because of this, the prosecution dropped the similar charges against Woodsworth.

For the "foreigners" arrested on June 17, there were no criminal trials. The attempt to deport Almazoff failed. Charitonoff successfully appealed against a deportation order. Blumenberg and Schoppelrei were deported for technical reasons related to how they first entered the country. Blumenberg later found success in the U.S., organizing workers and even running for local office on a socialist platform.

The Strike's Impact on Politics and Unions

A provincial investigation led by H.A. Robson looked into the strike. The report did not support sympathetic strikes. However, it concluded that the Winnipeg strike was not a criminal plot by foreigners. It stated that "if Capital does not provide enough to assure Labour a contented existence... then the Government might find it necessary to step in and let the state do these things at the expense of Capital."

The strike had a clear impact on later elections. Labour had elected some representatives before the strike, but their numbers greatly increased afterward at all levels of government.

While waiting for his trial, Queen was re-elected to the Winnipeg City Council. While in prison, Armstrong, Ivens, and Queen were elected to the Manitoba legislature. Queen later served seven terms as mayor of Winnipeg.

Woodsworth was elected as a Labour Member of Parliament for Winnipeg in 1921. He was re-elected many times until his death in 1942. In 1932, he helped start and became the leader of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation. This party was a forerunner of the New Democratic Party. That party was elected to provincial government in Saskatchewan in 1944 and in Manitoba in 1969. Heaps was elected as the Labour Member of Parliament for Winnipeg North in 1925 and re-elected until 1940.

Organized labour used the strike's legacy to make the union movement stronger. They also worked to get formal collective bargaining rights. The One Big Union grew quickly for a short time, reaching its peak popularity in 1920. Then, new industrial unions rose in the 1930s. The renewed poverty and uncertainty of the Great Depression led to a long period of labour activism across Canada in the 1940s. Union membership increased a lot during this time. By the end of that decade, a formal system for industrial relations was set up in Canadian law. This gave some security to unions and their members but also aimed to limit their activities.

Images for kids

See Also

- 1918 Vancouver general strike

- 1919 Seattle General Strike

- 1935 On-to-Ottawa Trek