History of Canada facts for kids

The history of Canada is a long and exciting story, starting thousands of years ago when the first people arrived in North America. Before Europeans came, many different Indigenous peoples lived across what is now Canada. They had their own ways of life, trade routes, spiritual beliefs, and social groups. Some of these ancient civilizations had disappeared long before the first Europeans arrived, and we learn about them through archaeological discoveries.

From the late 1400s, explorers from France and Britain came to North America. They explored, settled, and fought over different areas that are now part of Canada. New France was claimed in 1534, and permanent settlements began in 1608. After the Seven Years' War, France gave almost all its North American lands to the United Kingdom in 1763.

The British Province of Quebec was later split into Upper and Lower Canada in 1791. These two provinces joined together to form the Province of Canada in 1841. In 1867, the Province of Canada, along with New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, formed a new self-governing country called "Canada" through an event known as Confederation. Over the next 82 years, Canada grew by adding other British colonies, with Newfoundland and Labrador joining in 1949.

Even though Canada had a form of self-government since 1848, Britain still managed its foreign and defense policies until after the First World War. In 1931, the Statute of Westminster recognized Canada as an equal to the United Kingdom. Finally, in 1982, Canada gained full control over its own constitution, ending its legal dependence on the British Parliament. Today, Canada has ten provinces and three territories. It is a parliamentary democracy and a constitutional monarchy, meaning it has a parliament and a monarch (the King or Queen) as its head of state.

Over many centuries, Indigenous, French, British, and more recent immigrant cultures have mixed to create a unique Canadian culture. This culture has also been greatly shaped by its close neighbor, the United States. Since the end of the Second World War, Canadians have supported working with other countries and helping with global development.

Contents

- Ancient Peoples of Canada

- Canada Under French Rule (1534–1763)

- Canada Under British Rule (1763–1931)

- Canada During the Second World War

- Post-War Canada (1945–1960)

- Canada in the 1960s and 1970s (1960–1981)

- Canada in the 1980s and Early 1990s (1982–1992)

- Recent Canadian History (1992–Present)

- Images for kids

- See also

Ancient Peoples of Canada

First Nations and Inuit History

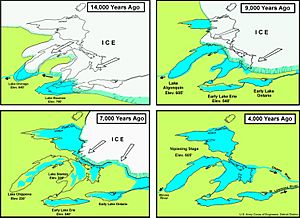

Scientists believe that North and South America were the last continents where humans settled. Between 50,000 and 17,000 years ago, during the Ice Age, sea levels dropped. This allowed people to cross a land bridge called Beringia from Siberia into North America. At first, a massive ice sheet covering most of Canada blocked their path, keeping them in Alaska and Yukon for thousands of years.

Around 16,000 years ago, the ice began to melt. This opened up paths for people to move south and east into Canada. Some of the oldest archaeological sites in Canada, like those in the Queen Charlotte Islands, Old Crow Flats, and Bluefish Caves, show signs of these early people. These Ice Age hunter-gatherers left behind stone tools and bones from large animals they hunted.

The climate in North America became stable around 8000 BCE (10,000 years ago). Conditions were similar to today, but large parts of the land were still covered by melting glaciers, forming many lakes. Most groups during this time were still nomadic hunter-gatherers. However, different groups began to focus on local resources. Over time, this led to unique regional cultures developing.

The Woodland cultural period lasted from about 2000 BCE to 1000 CE. It covered areas like Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritime regions. Pottery was introduced during this time, setting the Woodland culture apart from earlier groups. The Laurentian-related people of Ontario made the oldest pottery found in Canada.

The Hopewell tradition was an Aboriginal culture that thrived along American rivers from 300 BCE to 500 CE. Its trade network, called the Hopewell Exchange System, connected cultures as far north as the Canadian shores of Lake Ontario. Canadian groups influenced by the Hopewell tradition include the Point Peninsula, Saugeen, and Laurel complexes.

The eastern woodland areas of what became Canada were home to the Algonquian and Iroquoian peoples. The Algonquian language likely started in Idaho or Montana and spread eastward. It eventually reached from Hudson Bay to Nova Scotia and as far south as Virginia.

Speakers of eastern Algonquian languages included the Mi'kmaq and Abenaki in Canada's Maritime region, and probably the extinct Beothuk of Newfoundland. The Ojibwa and other Anishinaabe speakers of central Algonquian languages have stories about moving to the Great Lakes area from the east coast. The Ojibwa, Odawa, and Potawatomi formed the Council of Three Fires in 796 CE.

The Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) lived in northern New York from at least 1000 CE. Their influence reached into southern Ontario and the Montreal area. The Iroquois Confederacy was formed around 1142 CE. On the Great Plains, the Cree (who spoke a related Algonquian language) relied on bison herds for food and other needs. To the northwest were the Na-Dene language groups, including the Athapaskan-speaking peoples and the Tlingit. The Na-Dene language group might be linked to languages in Siberia. The Dene people of the western Arctic may represent a separate migration wave from Asia.

The interior of British Columbia was home to Salishan language groups like the Shuswap (Secwepemc) and Okanagan. It also had southern Athabaskan groups like the Dakelh (Carrier) and Tsilhqot'in. The coast of British Columbia had large, unique populations like the Haida, Kwakwaka'wakw, and Nuu-chah-nulth. They thrived on abundant salmon and shellfish. These peoples developed complex cultures using western red cedar. They built wooden houses, large canoes for whaling and war, and carved elaborate potlatch items and totem poles.

In the Arctic, the Dorset peoples, whose culture dates back to around 500 BCE, were replaced by the ancestors of today's Inuit by 1500 CE. This change is supported by archaeological findings and Inuit stories about driving off the Tuniit or 'first inhabitants'. Inuit traditional laws were different from Western laws. There was no formal "customary law" in Inuit society before the Canadian legal system was introduced.

Early European Explorers

There are stories of contact between First Nations, Inuit, and people from other continents before Christopher Columbus's voyages in 1492. The Norse, who had settled Greenland and Iceland, arrived around the year 1000. They built a small settlement at L'Anse aux Meadows on the northern tip of Newfoundland. This site is also linked to the attempted colony of Vinland, established by Leif Erikson around the same time.

After the Vikings, the Italian explorer John Cabot was the first European known to land in Canada. He was sent by King Henry VII of England. Records show that on June 24, 1497, he saw land somewhere in the Atlantic provinces. Many believe his first landing site was at Cape Bonavista, Newfoundland. After 1497, Cabot and his son Sebastian continued voyages to find a Northwest Passage. Other explorers also sailed from England to the New World, but their journeys are not well documented.

Based on the Treaty of Tordesillas, Spain claimed rights to the area Cabot visited. However, Portuguese explorers like João Fernandes Lavrador continued to visit the North Atlantic coast. This is why "Labrador" appears on old maps. In 1501 and 1502, the Corte-Real brothers explored Newfoundland and Labrador, claiming them for Portugal. In 1506, the King of Portugal taxed cod fisheries in Newfoundland waters. João Álvares Fagundes and Pêro de Barcelos set up fishing outposts in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia around 1521. These were later abandoned as Portuguese colonizers focused on South America. The full extent of Portuguese activity in Canada during the 16th century is still debated.

Canada Under French Rule (1534–1763)

French interest in the New World began in 1524. King Francis I of France sent Giovanni da Verrazzano to explore the region between Florida and Newfoundland. He hoped to find a route to the Pacific Ocean. Although England had claimed land in North America in 1497 through John Cabot, they did not try to settle permanently. For the French, Jacques Cartier planted a cross in the Gaspé Peninsula in 1534. He claimed the land for King Francis I, naming the region "Canada."

Early French attempts at permanent settlement failed. These included Cartier's efforts at Charlesbourg-Royal in 1541, and later attempts at Sable Island in 1598 and Tadoussac in 1600. Despite these failures, French fishing fleets sailed the Atlantic coast and into the St. Lawrence River. They traded and formed alliances with First Nations. They also set up fishing settlements like Percé in 1603. Because of France's claims and activities, the name "Canada" appeared on international maps for this colony in the St. Lawrence River region.

In 1604, Pierre Du Gua, Sieur de Mons, received a monopoly for the fur trade in North America. The fur trade became a major economic activity. Du Gua led his first settlement trip to an island near the mouth of the St. Croix River. One of his lieutenants was Samuel de Champlain, a geographer. Champlain explored the northeastern coastline of what is now the United States. In the spring of 1605, under Champlain's leadership, the St. Croix settlement moved to Port Royal (now Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia).

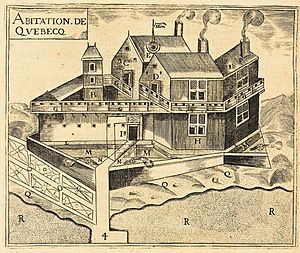

In 1608, Champlain founded Quebec City, one of the earliest permanent settlements. It became the capital of New France. Champlain managed the city and its affairs, sending expeditions to explore the interior. He discovered Lake Champlain in 1609. By 1615, he had traveled by canoe up the Ottawa River, through Lake Nipissing and Georgian Bay, to the heart of Huron country near Lake Simcoe. During these trips, Champlain helped the Wendat (Hurons) fight against the Iroquois Confederacy. As a result, the Iroquois became enemies of the French. They fought many conflicts, known as the French and Iroquois Wars, until the Great Peace of Montreal was signed in 1701.

The English, led by Humphrey Gilbert, claimed St. John's, Newfoundland, in 1583. This was the first English colony in North America, claimed by Queen Elizabeth I. Under King James I, the English established more colonies in Cupids and Ferryland, Newfoundland. Soon after, they founded the first successful permanent settlements in Virginia to the south. In 1621, King James granted a charter for a Scottish colony in the New World to Sir William Alexander. The first Scottish settlers left in 1622. They faced difficulties, and permanent Nova Scotian settlements were not firmly established until 1629, near the end of the Anglo-French War. These colonies did not last long. In 1631, King Charles I signed the Treaty of Suza, ending the war and returning Nova Scotia to the French. New France was fully restored to French rule in 1632 with the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. This led to new French immigrants and the founding of Trois-Rivières in 1634.

During this time, New France's inland frontier grew to cover a huge area. Unlike the English colonies, which focused on dense agricultural settlements near the coast, New France had a thin network. This network was centered on the fur trade, missionary efforts to convert Indigenous peoples, building an empire, and military actions to protect these efforts. This vast canoe network covered much of present-day Canada and parts of the central United States.

After Champlain's death in 1635, the Roman Catholic Church and the Jesuit missionaries became very powerful in New France. They hoped to create a perfect European and Aboriginal Christian community. In 1642, the Sulpicians sponsored a group of settlers led by Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve. They founded Ville-Marie, which is now Montreal. In 1663, the French crown took direct control of the colonies from the Company of New France.

Even though few immigrants came to New France under direct French control, most new arrivals were farmers. The population grew very quickly among the settlers already there. Women had about 30 percent more children than women who stayed in France. Historians say that "Canadians had an exceptional diet for their time." This was because of plenty of meat, fish, and clean water. Food could be preserved well in winter, and there was usually enough wheat. The 1666 census of New France, taken by Jean Talon, showed a population of 3,215 Acadians and habitants (French-Canadian farmers) in Acadia and Canada. The census also showed a big difference in numbers: 2,034 men compared to 1,181 women.

Colonial Wars in Canada

By the early 1700s, New France settlers were well established along the St. Lawrence River and parts of Nova Scotia, with about 16,000 people. However, new arrivals from France stopped coming in the following decades. This meant that by the 1750s, English and Scottish settlers in Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and the southern Thirteen Colonies greatly outnumbered the French population, by about ten to one. From 1670, the English, through the Hudson's Bay Company, also claimed Hudson Bay and its surrounding area, known as Rupert's Land. They set up new trading posts and forts, while continuing fishing settlements in Newfoundland.

French expansion along Canadian canoe routes challenged the Hudson's Bay Company's claims. In 1686, Pierre Troyes led an overland expedition from Montreal to Hudson Bay, capturing several outposts. La Salle's explorations gave France a claim to the Mississippi River Valley. There, fur trappers and a few settlers set up scattered forts and settlements.

There were four French and Indian Wars and two other wars in Acadia and Nova Scotia between the Thirteen American Colonies and New France from 1688 to 1763. During King William's War (1688 to 1697), military conflicts in Acadia included the Battle of Port Royal (1690), a naval battle in the Bay of Fundy, and the Raid on Chignecto (1696). The Treaty of Ryswick in 1697 briefly ended the war between England and France.

During Queen Anne's War (1702 to 1713), the British conquered Acadia in 1710. As a result, Nova Scotia (except Cape Breton) was officially given to the British by the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. This also included Rupert's Land, which France had conquered earlier. Because of this loss, France built the strong Fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island.

Louisbourg was meant to be a year-round military and naval base for France's remaining North American empire. It also protected the entrance to the St. Lawrence River. Father Rale's War led to the decline of New France's influence in Maine. It also made the British realize they needed to negotiate with the Mi'kmaq in Nova Scotia. During King George's War (1744 to 1748), an army of New Englanders attacked Louisbourg in 1745. The fortress surrendered within three months.

When Louisbourg was returned to French control by the peace treaty, the British founded Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1749 under Edward Cornwallis. Even though the war between Britain and France officially ended with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, conflict continued in Acadia and Nova Scotia during Father Le Loutre's War.

The British ordered the Acadians to be removed from their lands in 1755 during the French and Indian War. This event is known as the Expulsion of the Acadians or le Grand Dérangement. About 12,000 Acadians were sent to various places in British North America, France, Quebec, and the French Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue. The first wave of expulsions began with the Bay of Fundy Campaign in 1755. The second wave started after the final Siege of Louisbourg in 1758. Many Acadians settled in southern Louisiana, creating the Cajun culture there. Some Acadians managed to hide, and others eventually returned to Nova Scotia. However, they were greatly outnumbered by new settlers from New England who moved onto the former Acadian lands. Britain eventually took control of Quebec City and Montreal after the Battle of the Plains of Abraham and the Battle of Fort Niagara in 1759, and the Battle of the Thousand Islands and the Battle of Sainte-Foy in 1760.

Canada Under British Rule (1763–1931)

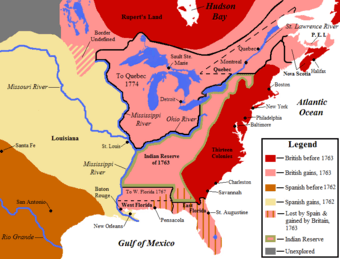

After the Seven Years' War ended and the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1763, France gave up almost all its remaining land in mainland North America. It kept only fishing rights off Newfoundland and two small islands, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, where its fishermen could dry their fish. France had already secretly given its huge Louisiana territory to Spain in 1762. This land included the entire Mississippi River drainage basin, from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico, and from the Appalachian Mountains to the Rocky Mountains. France and Spain kept this treaty secret from other countries until 1764. In exchange for Canada, Britain returned Guadeloupe to France. Guadeloupe was a very important sugar-producing colony, which the French at the time thought was more valuable than Canada.

The new British rulers of Canada largely kept and protected the property, religious, political, and social culture of the French-speaking habitants. The Quebec Act of 1774 guaranteed the right of the Canadiens to practice the Catholic faith and use French civil law (now Quebec law). The Royal Proclamation of 1763, issued in October by King George III, organized Great Britain's new North American empire. It also aimed to improve relations between the British Crown and Aboriginal peoples by regulating trade, settlement, and land purchases on the western frontier.

American Revolution and Loyalists

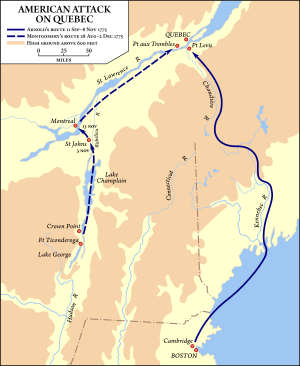

During the American Revolution, some Acadians and New Englanders in Nova Scotia felt sympathy for the American cause. However, neither group officially joined the rebels, though a few hundred individuals did. An invasion of Quebec by the Continental Army in 1775, aiming to take Quebec from British control, was stopped at the Battle of Quebec by Guy Carleton, with help from local militias. The defeat of the British army at the Siege of Yorktown in October 1781 signaled the end of Britain's fight to stop the American Revolution.

When the British left New York City in 1783, they took many Loyalist refugees to Nova Scotia. Other Loyalists went to southwestern Quebec. So many Loyalists arrived on the shores of the St. John River that a separate colony, New Brunswick, was created in 1784. In 1791, Quebec was divided into Lower Canada, which was mostly French-speaking, and Upper Canada, which was English-speaking and settled by Loyalists. Its capital was established in York (now Toronto) by 1796. After 1790, most new settlers were American farmers looking for new lands. They were generally in favor of republican ideas but remained neutral during the War of 1812.

The Treaty of Paris in 1783 officially ended the war. Britain made several agreements with the Americans that affected its North American colonies. Notably, the borders between Canada and the United States were officially drawn. All land south of the Great Lakes, which was part of the Province of Quebec and included modern-day Michigan, Illinois, and Ohio, was given to the Americans. Fishing rights were also granted to the United States in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and off the coast of Newfoundland and the Grand Banks. The British ignored part of the treaty and kept their military outposts in the Great Lakes areas they had given to the U.S. They also continued to supply their Native allies with weapons. The British left these outposts with the Jay Treaty of 1795, but the continued supply of weapons angered the Americans leading up to the War of 1812.

Canadian historians have different opinions on the long-term effects of the American Revolution. Arthur Lower, in the 1950s, argued that for English Canada, the results were against revolution. He said that English Canada "inherited, not the benefits, but the bitterness of the Revolution." He felt that English Canada started with a strong push backward into the past, similar to what the Conquest did for French Canada. He described them as "two little peoples officially devoted to counter-revolution, to lost causes."

More recently, Michel Ducharme agreed that Canada did oppose "republican liberty" like that in the United States and France. However, he says Canada found a different path. After 1837, Canadians fought against British rulers to gain "modern liberty." This type of liberty focused on protecting citizens' rights from government interference, rather than on the virtues of citizens.

War of 1812: Canada's Defense

The War of 1812 was fought between the United States and the British, with British North American colonies heavily involved. The American war plans focused on invading Canada, especially what is now eastern and western Ontario. American frontier states voted for war to stop First Nations raids that made settling the frontier difficult. The war along the border was marked by many failed invasions and mistakes on both sides.

American forces took control of Lake Erie in 1813. This forced the British out of western Ontario, killed the Native American leader Tecumseh, and broke the military power of his confederacy. British army officers like Isaac Brock and Charles de Salaberry oversaw the war. They were helped by First Nations and loyalist informants, especially Laura Secord.

The war ended with no changes to the borders, thanks to the Treaty of Ghent in 1814 and the Rush–Bagot Treaty of 1817. One result was that American migration shifted from Upper Canada to Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan, where there was no fear of Indian attacks. After the war, supporters of Britain tried to suppress republican ideas that were common among American immigrants to Canada. The difficult memory of the war and the American invasions made Canadians distrust the United States' intentions towards the British presence in North America.

Rebellions and the Durham Report

The rebellions of 1837 were against the British colonial government in both Upper and Lower Canada. In Upper Canada, a group of Reformers led by William Lyon Mackenzie took up arms. They fought a disorganized and unsuccessful series of small battles around Toronto, London, and Hamilton.

In Lower Canada, a more significant rebellion happened against British rule. Both English and French-Canadian rebels, sometimes using bases in the neutral United States, fought several battles against the authorities. The towns of Chambly and Sorel were taken by the rebels. Quebec City was cut off from the rest of the colony. Montreal rebel leader Robert Nelson read the "Declaration of Independence of Lower Canada" to a crowd in Napierville in 1838. The Patriote movement rebellion was defeated after battles across Quebec. Hundreds were arrested, and several villages were burned in revenge.

The British Government then sent Lord Durham to study the situation. He stayed in Canada for only five months before returning to Britain. He brought with him his Durham Report, which strongly suggested "responsible government." A less popular recommendation was to combine Upper and Lower Canada to deliberately make the French-speaking population more like the English. The Canadas were merged into a single colony, the United Province of Canada, by the Act of Union in 1840. Responsible government was achieved in 1848, a few months after it happened in Nova Scotia. The parliament of United Canada in Montreal was set on fire by a mob of Tories in 1849. This happened after a bill was passed to pay people who lost property during the rebellion in Lower Canada.

Between the Napoleonic Wars and 1850, about 800,000 immigrants came to the British North American colonies. Most came from the British Isles as part of the "great migration of Canada." These included Gaelic-speaking Highland Scots who were forced from their homes to Nova Scotia, and Scottish and English settlers to the Canadas, especially Upper Canada. The Irish Famine of the 1840s greatly increased Irish Catholic immigration to British North America. Over 35,000 struggling Irish people arrived in Toronto alone in 1847 and 1848.

Pacific Colonies and Expansion

Spanish explorers led the way on the Pacific Northwest coast, with voyages by Juan José Pérez Hernández in 1774 and 1775. By the time the Spanish decided to build a fort on Vancouver Island, the British navigator James Cook had visited Nootka Sound. He mapped the coast as far as Alaska. British and American fur traders had also started a busy trade with the coastal Indigenous peoples. They wanted sea otter pelts for the strong market in China, starting what was known as the China Trade.

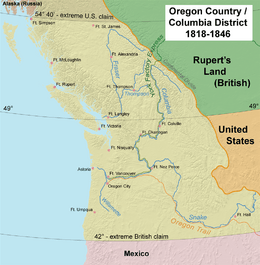

In 1789, war almost broke out between Britain and Spain over their rights. The Nootka Crisis was solved peacefully, mostly in favor of Britain, which had a much stronger navy. In 1793, Alexander MacKenzie, a Canadian working for the North West Company, crossed the continent. With his Aboriginal guides and French-Canadian crew, he reached the mouth of the Bella Coola River. He completed the first continental crossing north of Mexico, missing George Vancouver's mapping expedition by only a few weeks. In 1821, the North West Company and Hudson's Bay Company merged. Their combined trading territory expanded to include the North-Western Territory and the Columbia and New Caledonia fur districts, reaching the Arctic Ocean to the north and the Pacific Ocean to the west.

The Colony of Vancouver Island was established in 1849, with Fort Victoria as its capital. This was followed by the Colony of the Queen Charlotte Islands in 1853, and the Colony of British Columbia in 1858. The Stikine Territory was created in 1861. These last three were founded specifically to prevent American gold miners from taking over and claiming these regions. The Colony of the Queen Charlotte Islands and most of the Stikine Territory were merged into the Colony of British Columbia in 1863. The rest, north of the 60th Parallel, became part of the North-Western Territory.

Confederation: Birth of a Nation

The Seventy-Two Resolutions from the 1864 Quebec Conference and Charlottetown Conference created a plan to unite British colonies in North America into a federation. Most of the provinces of Canada adopted these resolutions. They became the basis for the London Conference of 1866, which led to the formation of the Dominion of Canada on July 1, 1867. The word dominion was chosen to show Canada's status as a self-governing colony within the British Empire. It was the first time this term was used for a country.

When the British North America Act came into force, the Province of Canada, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia became a federated kingdom. (The term "Dominion of Canada" was gradually used less in the late 1940s, 50s, and early 60s as Canadian nationalism grew.)

Confederation happened for several reasons. The British wanted Canada to defend itself. The Maritime provinces needed railway connections, which were promised in 1867. British-Canadian nationalists wanted to unite the lands into one country, dominated by English language and British culture. Many French-Canadians saw a chance to gain political control within a new, mostly French-speaking Quebec. There were also fears of possible U.S. expansion northward. Politically, there was a desire for more responsible government and to end the legislative disagreements between Upper and Lower Canada. They wanted to replace these with provincial legislatures in a federation. This was especially pushed by the liberal Reform movement of Upper Canada and the French-Canadian Parti rouge in Lower Canada, who favored a less centralized union. This was different from the Upper Canadian Conservative party and some of the French-Canadian Parti bleu, who wanted a more centralized union.

Early Post-Confederation Canada (1867–1914)

Canada's Land Grows

Ottawa used the promise of the Canadian Pacific Railway, a train line across the country, to gain support in the Maritimes and British Columbia. In 1866, the Colony of British Columbia and the Colony of Vancouver Island merged into a single colony. It joined the Canadian Confederation in 1871. In 1873, Prince Edward Island joined. Newfoundland, which didn't need a transcontinental railway, voted no in 1869 and didn't join Canada until 1949.

In 1873, John A. Macdonald, Canada's First Prime Minister, created the North-West Mounted Police (now the Royal Canadian Mounted Police). They helped police the Northwest Territories. Specifically, the Mounties were to show that Canada controlled the land and prevent possible American takeovers in the sparsely populated areas.

The Mounties' first big mission was to stop the second independence movement by Manitoba's Métis. The Métis are people of mixed First Nations and European descent. Their desire for independence led to the Red River Rebellion in 1869 and the later North-West Rebellion in 1885, led by Louis Riel. Stopping the Rebellion was Canada's first independent military action. It cost about $5 million and showed how important it was to finish the Canadian Pacific Railway. It ensured that English-speaking people controlled the Prairies and proved the national government could act decisively. However, it caused the Conservative Party to lose most of its support in Quebec and led to lasting distrust of English-speaking Canadians by French-speaking Canadians.

In 1905, Saskatchewan and Alberta became provinces. They were growing fast thanks to many wheat crops. This attracted immigrants to the plains from Ukraine, Northern and Central Europe, and settlers from the United States, Britain, and eastern Canada.

The Alaska boundary dispute, which had been ongoing since the Alaska purchase in 1867, became serious when gold was found in the Yukon in the late 1890s. The U.S. controlled all possible entry ports. Canada argued its border included the port of Skagway, Alaska. The dispute went to arbitration in 1903, but the British delegate sided with the Americans. This angered Canadians, who felt the British had betrayed Canadian interests to gain favor with the U.S.

In the 1890s, legal experts created a framework of criminal law, leading to the Criminal Code, 1892. This made the idea of "equality before the law" a real thing for every adult Canadian. Wilfrid Laurier, who was Prime Minister from 1896 to 1911, felt Canada was about to become a world power. He declared that the 20th century would "belong to Canada."

Laurier signed a trade agreement with the U.S. that would lower taxes on goods in both directions. Conservatives, led by Robert Borden, criticized it. They said it would make Canada's economy too dependent on the U.S. and weaken its ties with Britain. The Conservative party won the 1911 Canadian federal election.

Canadian Culture Develops

Canadian culture as we know it today began to take shape during the time of westward expansion. Canada's unique geography, climate, and mix of cultures all played a part. Because Canada is a cold country with long winter nights for most of the year, special leisure activities developed. These included hockey and snowshoeing. During this period, churches tried to guide leisure activities by speaking against drinking and organizing annual revivals and weekly club events. By 1930, radio became very important in uniting Canadians around their local or regional hockey teams. Live sports coverage, especially of ice hockey, captivated fans much more intensely than newspaper reports the next day. Rural areas were particularly influenced by sports coverage.

Canadians in the 19th century began to believe they had a unique "northern character." This was due to the long, harsh winters that only strong people could survive. This toughness was claimed as a Canadian trait. Sports like ice hockey and snowshoeing, which showed this trait, were seen as uniquely Canadian. Outside of sports, Canadians are often described as peaceful, orderly, and polite. But at ice hockey games, they cheer loudly for the speed, fierceness, and violence. This makes hockey an interesting symbol of Canada.

The Great War and Between Wars (1914–1939)

First World War Impact

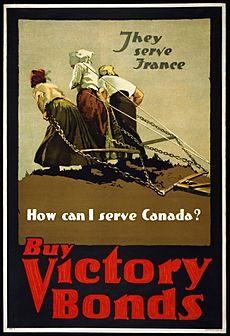

Canada's military and civilian involvement in the First World War helped create a sense of Canadian nationhood. The Canadian military achieved great success during battles like the Somme, Vimy Ridge, Passchendaele, and what became known as "Canada's Hundred Days." The strong reputation Canadian troops earned, along with the success of Canadian flying aces like William George Barker and Billy Bishop, gave the nation a new sense of identity. The War Office reported that about 67,000 Canadians were killed and 173,000 wounded during the war. This does not include civilian deaths from events like the Halifax Explosion.

Supporting Great Britain during the First World War caused a major political crisis over conscription (forced military service). French-speaking Canadians, mainly from Quebec, rejected these national policies. During the crisis, many "enemy aliens" (especially Ukrainians and Germans) were placed under government control. The Liberal party was deeply divided, with most of its English-speaking leaders joining the unionist government led by Prime Minister Robert Borden, the Conservative party leader. The Liberals regained their power after the war under William Lyon Mackenzie King, who served as prime minister for three separate terms between 1921 and 1949.

Women's Right to Vote

The National Council of Women of Canada strongly promoted women's political status without the vote from 1894 to 1918. They believed women could influence society through their personal impact and moral persuasion. This meant electing men with strong moral character and raising public-spirited sons. The National Council's view supported its goal of building Canada as a White settler nation. While the women's suffrage movement was important for giving White women political rights, it also used arguments that linked White women's right to vote to the need to protect the nation from "racial decline."

Women could vote locally in some provinces, like Canada West from 1850, where land-owning women could vote for school trustees. By 1900, other provinces adopted similar rules. In 1916, Manitoba led the way by giving women full voting rights. At the same time, women who supported voting rights also strongly supported the prohibition movement, especially in Ontario and the Western provinces.

The Military Voters Act of 1917 gave the right to vote to British women who were war widows or had sons or husbands serving overseas. Unionist Prime Minister Borden promised equal voting rights for women during the 1917 election campaign. After his big victory, he introduced a bill in 1918 to extend voting rights to women. This bill passed easily, but it did not apply to Quebec provincial and municipal elections. Women in Quebec gained full voting rights in 1940. The first woman elected to Parliament was Agnes Macphail of Ontario in 1921.

Between the Wars

Canada on the World Stage

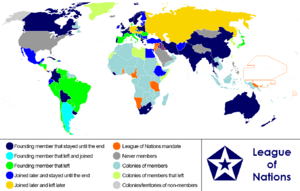

Because of its help in the Allied victory in the First World War, Canada became more confident and less dependent on British authority. Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden believed Canada had proven itself on the battlefields of Europe. He demanded that Canada have its own seat at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. At first, both Britain and the United States opposed this. They saw a Canadian delegation as an extra British vote. Borden argued that since Canada had lost nearly 60,000 men, a much larger proportion of its population, its right to equal status as a nation had been earned on the battlefield. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George eventually agreed. He convinced the reluctant Americans to accept delegations from Canada, India, Australia, Newfoundland, New Zealand, and South Africa. These countries also received their own seats in the League of Nations. Canada asked for no war payments or mandates. It played only a small role in Paris, but just having a seat was a matter of pride. Canada was cautiously hopeful about the new League of Nations, where it played an active and independent role.

In 1923, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George repeatedly asked for Canadian support in the Chanak crisis, where war threatened between Britain and Turkey. Canada refused. The Department of External Affairs, founded in 1909, grew and promoted Canadian independence. Canada reduced its reliance on British diplomats and used its own foreign service. This marked the start of careers for important diplomats like Norman Robertson, Hume Wrong, and future prime minister Lester Pearson.

Canadian Politics at Home

From 1921 to 1926, William Lyon Mackenzie King's Liberal government followed a cautious domestic policy. Its goals were to lower wartime taxes and, especially, to calm ethnic tensions from the war. It also aimed to ease labor conflicts after the war. The Progressives refused to join the government but helped the Liberals defeat motions of no confidence. King had to balance lowering tariffs enough to please the Prairie-based Progressives, but not so much that he would lose support in industrial Ontario and Quebec, which needed tariffs to compete with American imports.

King and Conservative leader Arthur Meighen argued constantly and fiercely in Parliament. The Progressives gradually became weaker. Their effective leader, Thomas Crerar, resigned to return to his grain business and was replaced by the calmer Robert Forke. The socialist reformer J. S. Woodsworth slowly gained influence among the Progressives. He reached an agreement with King on policy matters.

In 1926, Prime Minister Mackenzie King asked the Governor General, Lord Byng, to dissolve Parliament and call another election. But Byng refused. This was the only time a Governor General has used such a power. Instead, Byng asked Meighen, the Conservative Party leader, to form a government. Meighen tried, but he could not get a majority in Parliament. He also advised dissolution, which was accepted this time. This event, known as the King–Byng Affair, was a constitutional crisis. It was resolved by a new tradition of complete non-interference by the British government in Canadian political affairs.

The Great Depression in Canada

Canada was severely affected by the worldwide Great Depression, which started in 1929. Between 1929 and 1933, the country's total economic output dropped by 40%. Unemployment reached 27% at the worst point of the Depression in 1933. Many businesses closed, and corporate profits turned into losses. Canadian exports shrank by 50%. Construction almost stopped, and wholesale prices dropped by 30%. Wheat prices fell sharply from 78 cents per bushel in 1928 to 29 cents in 1932.

City unemployment across the country was 19%. Toronto's rate was 17%, according to the 1931 census. Farmers who stayed on their farms were not counted as unemployed. By 1933, 30% of the workforce was jobless, and one-fifth of the population relied on government help. Wages and prices fell. Areas that depended on primary industries like farming, mining, and logging were hit hardest. Most families had moderate losses, but some lost almost all their assets and suffered greatly.

In 1930, at the start of the Depression, Prime Minister Mackenzie King believed the crisis was temporary. He thought the economy would soon recover without government help. He refused to provide unemployment relief or federal aid to the provinces. He famously said he would not give them "a five cent piece." His blunt remark was used against the Liberals, leading to their defeat in the 1930 election. The main issue was the rapid decline of the economy and whether the prime minister understood the struggles of ordinary people.

Richard Bedford Bennett and the Conservatives won the 1930 election. Bennett had promised high tariffs and large government spending. But as government debt grew, he became cautious and severely cut federal spending. With falling support and the Depression worsening, Bennett tried to introduce policies similar to President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal in the United States, but he had little success. Bennett's government became a target of public anger. For example, car owners saved on gas by using horses to pull their cars, calling them "Bennett Buggies." The Conservative failure to bring back prosperity led to Mackenzie King's Liberals returning to power in the 1935 election.

In 1935, the Liberals used the slogan "King or Chaos" to win a huge victory in the 1935 election. Promising a much-desired trade treaty with the U.S., the Mackenzie King government passed the 1935 Reciprocal Trade Agreement. This was a turning point in Canadian-American economic relations. It reversed the disastrous trade war of 1930–31, lowered tariffs, and led to a dramatic increase in trade.

The worst of the Depression had passed by 1935. Ottawa launched relief programs like the National Housing Act and the National Employment Commission. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation became a government-owned company in 1936. Trans-Canada Airlines (now Air Canada) was formed in 1937, as was the National Film Board of Canada in 1939. In 1938, Parliament changed the Bank of Canada from a private company to a government-owned one.

One political response was a very strict immigration policy and a rise in nativism (favoring native-born citizens over immigrants). Times were especially hard in western Canada, where a full recovery didn't happen until the Second World War began in 1939. One response was the creation of new political parties like the Social Credit movement and the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation. There were also popular protests like the On-to-Ottawa Trek.

Canada Becomes Fully Independent

After the Balfour Declaration of 1926, the British Parliament passed the Statute of Westminster in 1931. This law recognized Canada as equal to the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth countries. It was a very important step in Canada becoming a separate state. It gave Canada almost complete power to make its own laws, independent of the British Parliament. Although the United Kingdom kept authority over any Canadian constitutional changes, this power was later given up with the passing of the Constitution Act, 1982. This was the final step in Canada achieving full independence.

Canada During the Second World War

Canada's involvement in the Second World War began when it declared war on Nazi Germany on September 10, 1939. Canada waited one week after Britain acted to show its independence. The war brought back Canada's economic health and confidence. Canada played a major role in the Atlantic Ocean and in Europe. During the war, Canada became more closely connected to the U.S. The Americans took control of Yukon to build the Alaska Highway and had a large presence in the British colony of Newfoundland with major airbases.

Mackenzie King and Canada were largely ignored by Winston Churchill and the British government. This was despite Canada's big role in supplying food, raw materials, weapons, and money to Britain. Canada also trained airmen for the Commonwealth, guarded the western North Atlantic Ocean against German U-boats, and provided combat troops for invasions of Italy, France, and Germany from 1943–45. The government successfully organized the economy for war, with impressive results in factories and farms. The Depression ended, prosperity returned, and Canada's economy grew significantly. Politically, Mackenzie King rejected the idea of a national unity government. The 1940 Canadian federal election was held as usual, giving the Liberals another majority.

Building up the Royal Canadian Air Force was a top priority. It was kept separate from Britain's Royal Air Force. The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan Agreement, signed in December 1939, committed Canada, Britain, New Zealand, and Australia to a program that trained half the airmen from those four nations in the Second World War.

After the war with Japan started in December 1941, the government, with the U.S., began the Japanese-Canadian internment. This sent 22,000 British Columbia residents of Japanese descent to camps far from the coast. The reason was strong public demand and fears of spying or sabotage. The government ignored reports from the RCMP and Canadian military that most Japanese Canadians were law-abiding and not a threat.

The Battle of the Atlantic began immediately. From 1943 to 1945, it was led by Leonard W. Murray from Nova Scotia. German U-boats operated in Canadian and Newfoundland waters throughout the war. They sank many naval and merchant ships, as Canada took charge of defenses in the western Atlantic. The Canadian army was involved in the failed defense of Hong Kong, the unsuccessful Dieppe Raid in August 1942, the Allied invasion of Italy, and the very successful invasion of France and the Netherlands in 1944–45.

The Conscription Crisis of 1944 greatly affected unity between French and English-speaking Canadians. However, it was not as politically disruptive as the one during the First World War. Out of a population of about 11.5 million, 1.1 million Canadians served in the armed forces in the Second World War. Many thousands more served with the Canadian Merchant Navy. In total, more than 45,000 died, and another 55,000 were wounded.

Post-War Canada (1945–1960)

Prosperity returned to Canada during the Second World War and continued in the years that followed. This period saw the development of universal health care, old-age pensions, and veterans' pensions. The financial crisis of the Great Depression had caused Newfoundland to give up its self-government in 1934 and become a British colony ruled by a governor. In 1948, the British government gave Newfoundland voters three choices: remain a British colony, return to being an independent Dominion, or join Canada. Joining the United States was not an option. After much debate, Newfoundlanders voted to join Canada in 1949 as a province.

Canada's foreign policy during the Cold War was closely linked to that of the United States. Canada was a founding member of NATO, which Canada also wanted to be a transatlantic economic and political union. In 1950, Canada sent combat troops to Korea during the Korean War as part of the United Nations forces. The federal government wanted to show its control over the Arctic during the Cold War. This led to the High Arctic relocation, where Inuit were moved from Nunavik (northern Quebec) to barren Cornwallis Island. This project was later investigated by the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.

In 1956, the United Nations responded to the Suez Crisis by forming a United Nations Emergency Force to oversee the withdrawal of invading forces. This peacekeeping force was first suggested by Lester B. Pearson, who was then Secretary of External Affairs and later became Prime Minister. Pearson won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1957 for his work in setting up this peacekeeping operation.

Throughout the mid-1950s, Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent and his successor John Diefenbaker tried to create a new, very advanced jet fighter, the Avro Arrow. Diefenbaker controversially canceled the aircraft in 1959. Instead, Diefenbaker bought the BOMARC missile defense system and American aircraft. In 1958, Canada established NORAD (North American Aerospace Defense Command) with the United States.

Canada in the 1960s and 1970s (1960–1981)

In the 1960s, Quebec experienced what became known as the Quiet Revolution. This movement changed the old system, which was centered on the Roman Catholic Church. It led to the modernization of Quebec's economy and society. Québécois nationalists demanded independence, and tensions grew until violence erupted during the October Crisis in 1970. Historian John Saywell said, "The two kidnappings and the murder of Pierre Laporte were the biggest domestic news stories in Canada's history." In 1976, the Parti Québécois was elected to power in Quebec. They had a nationalist vision that included protecting French language rights in the province and seeking some form of sovereignty for Quebec. This led to the 1980 referendum in Quebec on sovereignty-association, which was rejected by 59% of voters.

In 1965, Canada adopted the maple leaf flag. This decision caused much debate and concern among many English Canadians. The World's Fair, Expo 67, came to Montreal in 1967, coinciding with Canada's Centennial year. The fair opened on April 28, 1967, with the theme "Man and his World." It became the most attended world exposition up to that time.

Laws that had favored British and other European immigrants were changed in the 1960s. This opened the doors to immigrants from all over the world. While the 1950s saw many immigrants from Britain, Ireland, Italy, and northern continental Europe, by the 1970s, immigrants increasingly came from India, China, Vietnam, Jamaica, and Haiti. Immigrants from all backgrounds tended to settle in the major cities, especially Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver.

During his long time as Prime Minister (1968–79, 1980–84), Pierre Trudeau made social and cultural change his political goals. These included promoting official bilingualism in Canada and planning major constitutional changes. The west, especially oil-producing provinces like Alberta, opposed many policies coming from central Canada. The National Energy Program caused much anger and led to growing "western alienation." Multiculturalism was adopted as the official policy of the Canadian government during Pierre Trudeau's time as prime minister.

Canada in the 1980s and Early 1990s (1982–1992)

In 1982, the Canada Act was passed by the British Parliament and approved by Queen Elizabeth II on March 29. At the same time, the Constitution Act was passed by the Canadian Parliament and approved by the Queen on April 17. This brought the Constitution of Canada home. Before this, the constitution was only a British law and not even physically in Canada, though it couldn't be changed without Canadian agreement. Canada now had complete independence as a country, with the Queen's role as monarch of Canada separate from her role as the British monarch or monarch of other Commonwealth countries.

At the same time, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms was added, replacing the previous Bill of Rights. Bringing the constitution home was Trudeau's last major act as Prime Minister; he resigned in 1984.

The Progressive Conservative (PC) government of Brian Mulroney began efforts to get Quebec's support for the Constitution Act 1982 and end western alienation. In 1987, the Meech Lake Accord talks started between provincial and federal governments. They sought constitutional changes that would be good for Quebec. The failure of the Meech Lake Accord led to the formation of a separatist party, the Bloc Québécois. The constitutional reform process under Prime Minister Mulroney ended with the failure of the Charlottetown Accord. This accord would have recognized Quebec as a "distinct society" but was rejected by a small margin in 1992.

Under Brian Mulroney, relations with the United States became more closely linked. In 1986, Canada and the U.S. signed the "Acid Rain Treaty" to reduce acid rain. In 1989, the federal government adopted the Free Trade Agreement with the United States. This happened despite strong opposition from the Canadian public, who worried about the economic and cultural effects of being so closely linked to the United States.

On July 11, 1990, the Oka Crisis began. This was a land dispute between the Mohawk people of Kanesatake and the nearby town of Oka, Quebec. This dispute was one of several well-known conflicts between First Nations and the Canadian government in the late 20th century. In August 1990, Canada was one of the first nations to condemn Iraq's invasion of Kuwait. It quickly agreed to join the U.S.-led coalition. Canada sent destroyers and later a CF-18 Hornet squadron with support staff, as well as a field hospital to help with casualties.

Recent Canadian History (1992–Present)

After Mulroney resigned as prime minister in 1993, Kim Campbell took office. She became Canada's first female prime minister. Campbell was in office for only a few months. The 1993 election saw the Progressive Conservative Party collapse from government to just two seats. The Quebec-based separatist Bloc Québécois became the official opposition. Jean Chrétien of the Liberals took office in November 1993 with a majority government. He was re-elected with more majorities in the 1997 and 2000 elections.

In 1995, the government of Quebec held a second referendum on sovereignty. It was rejected by a very close margin of 50.6% to 49.4%. In 1998, the Canadian Supreme Court ruled that a province could not unilaterally separate (leave on its own) without negotiation. Parliament then passed the Clarity Act, which outlined the rules for a negotiated departure. Environmental issues became more important in Canada during this time. This led to Canada's Liberal government signing the Kyoto Accord on climate change in 2002. However, Prime Minister Stephen Harper's Conservative government later canceled the accord in 2007. They proposed a "made-in-Canada" solution to climate change.

Canada became the fourth country in the world and the first in the Americas to legalize same-sex marriage nationwide. This happened with the Civil Marriage Act. Court decisions, starting in 2003, had already made same-sex marriage legal in eight out of ten provinces and one of three territories. Before the Act passed, more than 3,000 same-sex couples had married in these areas.

The Canadian Alliance and PC Party merged to form the Conservative Party of Canada in 2003. This ended a 13-year split of the conservative vote. The party was elected twice as a minority government under Stephen Harper in the 2006 and 2008 federal elections. Harper's Conservative Party won a majority in the 2011 federal election. The New Democratic Party became the Official Opposition for the first time.

Under Harper, Canada and the United States continued to combine state and provincial agencies to improve security along the Canada–United States border. This was done through the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative. From 2002 to 2011, Canada was involved in the Afghanistan War. This was part of the U.S. stabilization force and the NATO-commanded International Security Assistance Force. In July 2010, the largest purchase in Canadian military history was announced. It was for C$9 billion to acquire 65 F-35 fighters. Canada is one of several nations that helped develop the F-35 and has invested over C$168 million in the program.

On October 19, 2015, Stephen Harper's Conservatives were defeated by a newly strong Liberal party. This party was led by Justin Trudeau and had been reduced to third-party status in the 2011 elections.

Multiculturalism (cultural and ethnic diversity) has been a focus in recent decades. Experts Ambrose and Mudde say that Canada's unique multiculturalism policy combines selective immigration, thorough integration, and strong government action against disagreement on these policies. This unique mix of policies has led to relatively low opposition to multiculturalism.

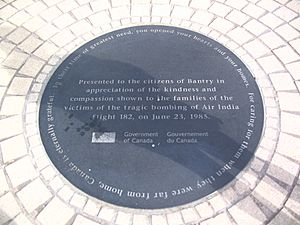

Images for kids

-

Jacques Cartier meeting with the St. Lawrence Iroquoians at Hochelaga during his second voyage in 1535.

-

British soldiers and the Canadian militia repel an American column during the Battle of Quebec.

-

A Black Loyalist wood cutter in Shelburne, Nova Scotia in 1788. After the American Revolutionary War, the remaining colonies of British North America saw an influx of loyalist migrants.

-

A train filled with soldiers departs from Toronto's Union Station shortly after the First World War began in 1914.

-

The German delegate is portrayed signing the peace treaties at the Paris Peace Conference, surrounded by Allied delegates. The Canadian delegate, George Foster is visible in the back row (fourth from the left).

-

Canadian prime minister Louis St. Laurent shakes hands with Albert Walsh, after delegates from Canada and Newfoundland sign the agreement to admit Newfoundland into Confederation.

-

A Royal Canadian Air Force CIM-10 Bomarc missile. Acquired as an alternative to the defunct Avro Arrow program, its adoption garnered controversy given its nuclear payload.

-

The March of Hearts rally in support of same-sex marriage at Parliament Hill in 2004. Same sex marriage was legalized in 2005 with the passage of the Civil Marriage Act.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Canadá para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Canadá para niños

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |