United Empire Loyalist facts for kids

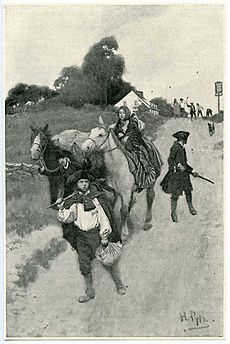

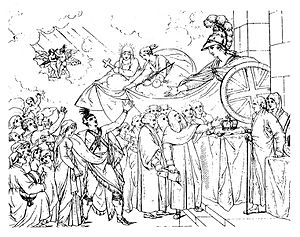

Reception of the American Loyalists by Great Britain in the Year 1783. This picture shows Loyalists asking for help from Britannia after being forced out of the United States.

|

|

| Abbreviation | UEL |

|---|---|

| Formation | 9 November 1789 |

| Purpose | Honorific title |

| Origins | Loyalists (American Revolution) |

|

Region served

|

British Empire, Canada |

A United Empire Loyalist (often called UEL or just Loyalist) is a special title. It was first given by Lord Dorchester, who was the Governor of Quebec and later the Governor General of the Canadas. He gave this title to American Loyalists who moved to British North America (which is now Canada) during or after the American Revolution.

At that time, the word "Canadian" or "Canadien" was used for the Indigenous peoples and the families of early French settlers in Quebec.

These Loyalists mostly settled in Nova Scotia and Quebec. So many Loyalists arrived that new colonies were created. In 1784, New Brunswick was separated from Nova Scotia because many Loyalists settled around the Bay of Fundy. The large number of Loyalist refugees also caused Quebec to be split into Lower Canada (now Quebec) and Upper Canada (now Ontario) in 1791.

The British Crown gave each Loyalist family a land grant of 200 acres (about 81 hectares). This was to encourage them to move and help develop the new areas, especially Upper Canada. This move brought many English speakers to Canada. It started new waves of immigration that helped create a mostly English-speaking population in what would become Canada.

Contents

History of the Loyalists

Leaving the United States

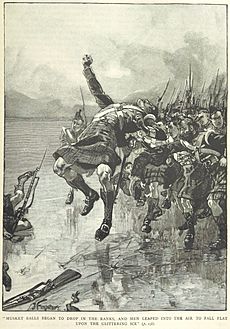

After the American Revolutionary War ended and the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783, many Loyalist soldiers and civilians left New York City. Most of them went to Canada. Many Loyalists had already moved to Canada, especially from New York and northern New England. This was because violence against them had grown during the war.

The British Crown sometimes gave land in Canada based on which Loyalist army regiment a man had served in. This movement of Loyalists was very important for the growth of present-day Ontario. About 10,000 refugees went to Quebec (including areas that are now Ontario). But Nova Scotia (which included New Brunswick at the time) received even more: about 35,000 to 40,000 Loyalist refugees.

Some Loyalists did not stay in Canada and eventually returned to the United States. Many Loyalist families had members on both sides during the war. So, Loyalists in Canada often kept in touch with their relatives in the United States. They even traded across the border, sometimes ignoring British trade rules.

In the 1790s, the offer of land and low taxes (which were much lower than in America) by Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe led to 30,000 more Americans arriving. These were often called "Late Loyalists." By the time the War of 1812 started, Upper Canada had about 110,000 people. Of these, 20,000 were the first Loyalists, 60,000 were later American immigrants and their families, and 30,000 were from the UK or Quebec. Many people came to Upper Canada later, suggesting that land was the main reason for their move.

New Homes in Canada

When the Loyalists arrived after the Revolutionary War, Canada was divided into Upper Canada (now southern Ontario) and Lower Canada (now southern Quebec). The Loyalists were often settled in groups based on their background and religion. Many soldiers settled with others from their old regiments. These settlers came from all parts of society and all thirteen colonies. This was different from how they are sometimes shown as only being wealthy people.

Loyalists soon asked the government to let them use the British legal system. They were used to this system from the American colonies. Great Britain had kept the French legal system and allowed freedom of religion after taking over the French colony in the Seven Years' War. With the creation of Upper and Lower Canada, most Loyalists in the west could live under British laws. The French-speaking people in Lower Canada could keep their French civil law and Catholic religion.

To recognize these loyal people, Lord Dorchester, the governor of Quebec, made an important statement on November 9, 1789. He said he wanted to "put the mark of Honour upon the Families who had adhered to the Unity of the Empire." Because of this, the official army lists began to use the letters "UE" or "U.E." next to the names of Loyalists. These letters stood for "Unity of the Empire," showing their strong belief in staying united with the British Empire.

Many Iroquois and other Indigenous peoples had sided with the British. When their lands were given to the United States, thousands of them were also forced to leave New York and other states. They were resettled in Canada. Many Iroquois, led by Joseph Brant, settled at Six Nations of the Grand River. This is the largest reserve for First Nations in Canada. A smaller group of Iroquois, led by Captain John Deserontyon, settled by the Bay of Quinte in southeastern Ontario.

About 3,500 Black Loyalists were settled in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. However, they faced unfair treatment and did not get enough support, just like other Loyalists. There were delays in giving them land grants. Also, some white Loyalists were upset because Black Loyalists would work for lower wages. This led to tensions, and in July 1784, white Loyalists attacked Black Loyalists in the Shelburne Riots. This was Canada's first "race" riot. The government was slow to survey the land for Black Loyalists. They also gave them smaller, poorer, and more distant lands than white settlers. This made it very hard for them to get established. Most Black Loyalists in Canada had come from the American South. They suffered from this unfair treatment and the harsh winters.

When Great Britain created the colony of Sierra Leone in Africa, almost 1,300 Black Loyalists moved there in 1792. They were promised self-government. About 2,200 Black Loyalists stayed in Canada. Those who left helped establish Freetown in Sierra Leone. For a long time, they and their descendants played a major role in the culture, economy, and government of Sierra Leone.

Many Loyalists had to leave a lot of property behind in the United States. Britain tried to get this property back or get money for it from the United States. This was a big issue when the Jay Treaty was being discussed in 1795. The agreement was that U.S. negotiators would "advise" the U.S. Congress to pay for the lost property. For the British, this "advice" was very important legally, much more than it was for the Americans. The U.S. Congress did not follow the advice.

Slavery in Canada

Some Loyalists who owned slaves brought them to Canada, as slavery was still legal there. They brought about 2,000 slaves to British North America. About 500 went to Upper Canada (Ontario), 300 to Lower Canada (Quebec), and 1,200 to the Maritime colonies (New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island). The presence of slaves in the Maritimes became a particular issue because they made up a larger part of the population, even though there wasn't large-scale plantation farming.

Many of these slaves were eventually freed by their owners. Along with the free Black Loyalists, many chose to go to Sierra Leone in 1792 and later years, hoping for a chance to govern themselves. In 1790, the British Parliament passed a law that allowed new immigrants to Canada to keep their slaves. However, in 1793, an anti-slavery law was passed in the 1st Parliament of Upper Canada. This Act Against Slavery stopped new slaves from being brought into the colony. It also said that children born to female slaves would become free when they turned 25. This law was partly a response to the number of slaves brought by Loyalist refugees to Upper Canada. The slave trade was banned across the British Empire in 1807. Slavery itself was abolished throughout the British Empire by 1834.

War of 1812 and Loyalists

From 1812 to 1815, the United States and the United Kingdom fought in the War of 1812. On June 18, 1812, US President James Madison signed the declaration of war. He was pressured by politicians in Congress who wanted to fight.

By 1812, Upper Canada was mostly settled by Loyalists from the American Revolution and later American and British immigrants. The Canadian colonies were not very populated and were only lightly defended by the British Army and local militias. American leaders thought Canada would be easy to take over. Former president Thomas Jefferson even said conquering Canada would be "a matter of marching."

Many Loyalists had moved to Upper Canada after the Revolutionary War. However, there were also many American settlers who were not Loyalists, as they had been offered land grants. The Americans thought these settlers would support them, but they did not. Even though many people in Upper Canada were recent settlers from the United States, American forces faced strong resistance from them during the War of 1812.

Many Loyalists served in different military groups, like the fencibles (local soldiers) or the Canadian Militia. The Canadian colonies successfully defended themselves from American invasion. Because of this, Loyalists see the War of 1812 as a victory. After the war, the British government moved about 400 of 3,000 former slaves to New Brunswick. These slaves had been freed during and after the war, as Britain had promised them freedom if they left American slaveholders and fought with the British. Enslaved African Americans took great risks to cross to British lines to gain their freedom.

Loyalists Today

The special title "United Empire Loyalist" is not an official part of Canada's honours system today. However, modern descendants of Loyalist refugees can still use it. Sometimes they use "U.E." after their names. This practice is not very common now, even in places like southeastern Ontario where many Loyalists first settled. But historians and family researchers often use it to quickly identify the family history of certain people.

The influence of the Loyalists on how Canada developed is still clear. Their strong connection to Britain and their dislike of the United States helped Canada stay independent and unique in North America. The Loyalists' basic distrust of republicanism (a system where power is held by elected representatives) and "mob rule" (rule by a crowd) shaped Canada's slow, peaceful path to independence.

The new British North American provinces of Upper Canada (which became Ontario) and New Brunswick were created as safe places for the United Empire Loyalists. The mottos of these two provinces show this history. Ontario's motto, also on its coat of arms, is Ut incepit fidelis sic permanet ("Loyal she began, loyal she remains"). New Brunswick's motto is Spem Reduxit ("Hope restored").

The word "Loyalist" appears often in the names of schools, streets, and businesses in communities settled by Loyalists, like Belleville, Ontario. The nearby city of Kingston, which was a Loyalist stronghold, was named to honour King George III. And just outside that city is a township simply called "Loyalist".

Canada's 2021 Census estimated that 10,015 people identify as having United Empire Loyalist origins.

On July 1, 1934, Royal Mail Canada released a stamp called "United Empire Loyalists, 1776–1784." It was designed by Robert Bruce McCracken and based on Sydney March's sculpture United Empire Loyalists.

In 1996, Canadian politicians Peter Milliken and John Godfrey (who was a descendant of American Loyalists) supported the Godfrey–Milliken Bill. This bill would have allowed Loyalist descendants to get back family property in the United States that was taken during the American Revolution. The bill did not pass in the House of Commons. It was mainly meant as a funny response to an American law called the Helms–Burton Act at the time.

In 1997, the Legislative Assembly of Ontario passed a law declaring June 19 as "United Empire Loyalist Day" in Ontario. United Empire Loyalist Day is also celebrated on the same day in Saskatchewan. It is celebrated on May 18 in New Brunswick and on July 22 in British Columbia.

Remembering the Loyalists

The Loyalists paid close attention to their own history. They created an ideal image of themselves that they were very proud of. In 1898, Henry Coyne wrote a very positive description:

The Loyalists, to a considerable extent, were the very cream of the population of the Thirteen Colonies. They represented in very large measure the learning, the piety, the gentle birth, the wealth and good citizenship of the British race in America, as well its devotion to law and order, British institutions, and the unity of the Empire. This was the leaven they brought to Canada, which has leavened the entire Dominion of this day.

Canadian historians Margaret Conrad and Alvin Finkel say that Coyne's description includes important ideas often used in patriotic celebrations. The Loyalist tradition, as explained by Murray Barkley and Norman Knowles, includes:

The elite origins of the refugees, their loyalty to the British Crown, their suffering and sacrifice in the face of hostile conditions, their consistent anti-Americanism, and their divinely inspired sense of mission.

Conrad and Finkel point out some exaggerations. Only a small number of Loyalists were from the colonial elite. In fact, Loyalists came from all levels of society. Also, few of them suffered extreme violence or hardship. About 20 percent later returned to the United States. Most were loyal to everything British, but some Loyalists even supported the United States in the War of 1812. Conrad and Finkel conclude:

[I]n using their history to justify claims to superiority, descendants of the Loyalists abuse the truth and actually diminish their status in the eyes of their non-Loyalists neighbours ... The scholars who argue that the Loyalists planted the seeds of Canadian liberalism or conservatism in British North America usually fail to take into account not only the larger context of political discussion that prevailed throughout the North Atlantic world, but also the political values brought to British North America by other immigrants in the second half of the 18th century.

From the 1870s, many Loyalist descendants moved back to the United States to find cheaper land. In the New England states alone, more than 10% of the people can trace their family roots to the Maritime Provinces of Canada.

United Empire Loyalists' Association

The association's coat of arms

|

|

| Abbreviation | UELAC |

|---|---|

| Formation | 27 May 1914 |

| Legal status | Charity |

| Purpose | Cultural, historical, hereditary association |

| Headquarters | George Brown House 50 Baldwin Street, Suite 202 Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

|

President

|

Patricia Groom |

The United Empire Loyalists' Association of Canada (UELAC) is a group for descendants of Loyalists and anyone interested in Canadian history. They focus on the role of the United Empire Loyalists. The group was officially formed on May 27, 1914, by the Legislative Assembly of Ontario. In 1972, the organization was given a special coat of arms from the College of Arms.

Loyalist Symbols

On April 17, 1707, Queen Anne announced that the Union Flag could be used "at Sea and Land." This flag began to appear on forts and as army flags from that time. During the American Revolution, this was the flag in use. When people loyal to the British Crown left the United States for British North America, they brought this flag with them. Because of this historical link, it is still the official flag of the UELAC today.

In Canadian heraldry (the study of coats of arms), descendants of Loyalists are allowed to use a special Loyalist coronet (a small crown) in their coat of arms.

Places Settled by Loyalists in Canada

Here are some places settled by Loyalists. The old names are listed first, followed by their modern names.

- Adolphustown, Ontario

- Antigonish, Nova Scotia

- Beamsville, Ontario

- Bocabec, New Brunswick

- Meyer's Creek → Belleville, Ontario

- Buell's Bay → Brockville, Ontario

- Butlersbury → Newark → Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario

- Cataraqui → Kingston, Ontario

- Clifton → Niagara Falls, Ontario

- Country Harbour, Nova Scotia

- Cobourg, Ontario

- Colchester → village now within Essex, Ontario

- Cornwall, Ontario

- Digby, Nova Scotia

- Doaktown, New Brunswick

- Eastern Townships, Quebec

- Effingham, Ontario

- Fredericton, New Brunswick

- Grimsby, Ontario

- Douglas Township → Kennetcook, Nova Scotia

- Lincoln, Ontario

- Ernestown Township → Loyalist, Ontario

- Machiche → Yamachiche, Quebec

- Merrittsville → Welland, Ontario

- Milliken Corners Milliken, Ontario

- Gravelly Bay → Port Colborne, Ontario

- Port Roseway → Shelburne, Nova Scotia

- Prescott, Ontario

- Prince Edward County, Ontario

- Rawdon, Nova Scotia

- Saint John, New Brunswick

- Sheet Harbour, Nova Scotia

- Shelburne, Nova Scotia

- Six Nations and Brantford, Ontario

- Smithville, Ontario

- St. Andrews by-the-Sea → St. Andrews, New Brunswick

- St. Anne's Point → Fredericton, New Brunswick

- Summerville, Nova Scotia

- The Twelve → Shipman's Corners → St. Catharines, Ontario

- Turkey Point → Norfolk, Ontario

- Sandwich → Windsor, Ontario

- Odell Town, Quebec

- Wainfleet, Ontario

- Remsheg → Wallace, Nova Scotia

- Westchester, Nova Scotia

- York → Toronto, Ontario

See also

In Spanish: Lealista del Imperio Unido para niños

In Spanish: Lealista del Imperio Unido para niños

- Expulsion of the Loyalists

- Loyalist (American Revolution)

- Canadian honorifics

- History of monarchy in Canada

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |