Joseph Brant facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Joseph Brant

Thayendanegea |

|

|---|---|

A 1776 portrait of Brant by leading court painter George Romney

|

|

| Born |

Thayendanegea

March 1743 Ohio Country somewhere along the Cuyahoga River

|

| Died | November 24, 1807 (aged 64) |

| Nationality | Mohawk |

| Spouse(s) |

Neggen Aoghyatonghsera

(m. 1765; died 1771)Susanna Aoghyatonghsera

(died) |

| Children | John Brant |

| Relatives | Molly Brant (sister) |

| Signature | |

|

|

Thayendanegea or Joseph Brant (born March 1743 – died November 24, 1807) was an important Mohawk leader. He was a military and political figure during and after the American Revolutionary War. He met many famous people of his time, including George Washington and King George III.

During the American Revolutionary War, Brant led Mohawk warriors and British supporters called "Loyalists". They fought against the American rebels in New York. Some Americans accused him of terrible acts and called him "Monster Brant". However, later historians said these accusations were not true.

Contents

Joseph Brant's Life Story

Growing Up

Joseph Brant was born in the Ohio Country in March 1743. His exact birthplace was somewhere along the Cuyahoga River. The Mohawk people followed a matrilineal culture. This meant he was born into his mother's Wolf Clan.

His parents were Christians named Peter and Margaret Tehonwaghkwangearahkwa. Joseph's father died when he was young.

After his father's death, his mother Margaret (Owandah) moved back to province of New York. She took Joseph and his sister Mary (Molly) with her. His mother later remarried. Her new husband was known as Barnet or Bernard, which became Brant.

They settled in Canajoharie, a Mohawk village on the Mohawk River. This was where they had lived before. In Mohawk society, young men like Brant were expected to become warriors.

The area where Brant grew up was settled by German immigrants called Palatines. They came from what is now Germany. The Palatines and Mohawks were friendly. Brant grew up hearing Mohawk, German, and English.

As a teenager, Brant was described as friendly and easy-going. He spent his days hunting and fishing with friends in the forests. During these trips, he often visited Palatine and Scots-Irish settlers. He would ask for food and talk with them. People remembered Brant for his charm.

War and Learning

When he was 15, Brant joined Mohawk and other Iroquois warriors. They fought with the British against the French in Canada. He was one of 182 Native American warriors who received a silver medal from the British for his service.

In 1761, his brother-in-law, Sir William Johnson, helped Brant and two other Mohawk boys get an education. They went to Eleazar Wheelock's "Moor's Indian Charity School" in Connecticut. Brant learned to speak, read, and write English. He also studied other school subjects.

Brant learned farming at the school, which was usually women's work for the Iroquois. He also studied math and classic books. Europeans were surprised when Brant could talk about the Odyssey with them. He met Samuel Kirkland there, who later became a missionary to Native Americans. In 1763, Brant left the school when his sister Molly asked him to return home.

Johnson then planned for Brant to attend King's College in New York City. However, Pontiac's Rebellion started, and Brant returned home. It was not safe for him to go to King's College.

During Pontiac's Rebellion, people on both sides saw it as a racial war. Being an Indigenous person loyal to the British was difficult for Brant. Mohawk men gained respect as warriors, not scholars. So, Brant stopped his studies to fight for the British.

In February 1764, Brant joined Mohawk and Oneida warriors. They fought alongside the British forces.

Family Life

On July 22, 1765, Brant married Peggie (also known as Margaret) in Canajoharie. She was said to be the daughter of Virginia settlers. Peggie had been captured by Native Americans when she was young. She became part of their culture and was sent to the Mohawk. They lived with his parents, who later gave their house to Brant.

Brant also owned a large farm of about 80 acres (32 hectares) near Canajoharie. This village was also called the Upper Mohawk Castle. Brant and Peggie grew corn and raised animals like cattle, sheep, horses, and hogs. He also ran a small store. Brant dressed in "the English mode," wearing a blue cloth suit.

Peggie and Brant had two children, Isaac and Christine. Sadly, Peggie died from tuberculosis in March 1771. Later, his son Isaac died in a difficult confrontation, which deeply affected Brant for the rest of his life.

Brant married a second wife, Susanna. She died near the end of 1777 during the American Revolutionary War. They were staying at Fort Niagara at the time.

While at Fort Niagara, Brant began living with Catharine Adonwentishon Croghan. He married her in the winter of 1780. She was the daughter of Catharine (Tekarihoga), a Mohawk woman, and George Croghan. Croghan was an important Irish colonist and British agent for Indigenous affairs. Through this marriage, Brant also became connected to John Smoke Johnson, a Mohawk godson of Sir William Johnson.

With Catherine Croghan, Brant had seven children: Joseph, Jacob, John, Margaret, Catherine, Mary, and Elizabeth.

His Work and Role

Joseph Brant was not born into a leadership role in the Iroquois League. However, he became important because of his education, skills, and connections to British officials.

With encouragement from Sir William Johnson, the Mohawk people named Brant a war chief. He also became their main spokesperson.

In the spring of 1772, Brant moved to Fort Hunter. He stayed with Reverend John Stuart. Brant became Stuart's interpreter and taught him Mohawk. They worked together to translate Christian texts, like the Anglican catechism and the Gospel of Mark, into the Mohawk language. Brant's interest in translating Christian texts started during his early education. He did many translations at Moor's Charity School.

From 1766 onwards, he worked as an interpreter for the British Indian Department.

The American Revolution

In 1775, Brant was made a Captain for the British Superintendent's Mohawk warriors from Canajoharie. The American Revolution began in April 1775. In May 1775, Brant went to a meeting at German Flatts to talk about the crisis.

On November 11, 1775, Irish diplomat Guy Johnson took Brant with him to London. They went to ask the British government for more support. Brant met George III during this trip. But his most important talks were with the colonial secretary, George Germain. Brant explained that the Iroquois had fought for the British in the Seven Years' War and lost many people. Yet, the British were letting white settlers take their land unfairly. The British government promised the Iroquois land in Quebec if they would fight on the British side.

In London, Brant was treated like a celebrity. He was interviewed by James Boswell for publication. King George III received him at St. James's Palace. In public, Brant wore traditional Mohawk clothing. He also became a freemason and received his special apron from King George himself.

During the war, he took part in many battles and was wounded twice.

After the War

In 1784, Frederick Haldimand gave Joseph Brant and his followers a land treaty. This was to replace the land they had lost in New York State. This land, called the Haldimand Grant, was about 2 million acres (809,000 hectares) in size. It was 12 miles (19.2 kilometers) wide along the Ouse or Grand River in what is now southwestern Ontario. Chief Brant and most of his people moved to Upper Canada. This area is now the Six Nations Reserve. He remained an important leader there.

His Death

Joseph Brant died in his home near Lake Ontario (now Burlington, Ontario) on November 24, 1807. He was 64 years old and had a short illness. His last words were to his adopted nephew, John Norton. He said, "Have pity on the poor Indians. If you have any influence with the great, endeavor to use it for their good." These words show his lifelong dedication to his people.

In 1850, his remains were carried 34 miles (55 kilometers) by young men of Grand River. They took him to a tomb at Her Majesty's Chapel of the Mohawks in Brantford.

His Legacy

Brant worked tirelessly to help the Six Nations control their land. He wanted them to do this without the British Crown's direct control.

Brant was a war chief, not a traditional Mohawk sachem (hereditary chief). His natural abilities, early education, and connections made him one of the great leaders of his time.

His main goal was to help Indigenous people survive big changes. He wanted them to adapt to new cultures, politics, and economies. He put his loyalty to the Six Nations before his loyalty to the British. His life was full of challenges and struggles.

Some parts of Brant's life are debated today. This includes the fact that he owned African slaves. This practice was unfortunately common among some people, including some Indigenous leaders, during that time.

Interesting Facts About Joseph Brant

- At birth, he was named Thayendanegea. In the Mohawk language, this means "He places two bets together."

- His sister, Molly Brant, was the wife of Sir William Johnson. Johnson was an important British official for Indigenous affairs in New York.

- Brant's mother, Margaret, was a successful businesswoman. She collected and sold ginseng, which was valuable for medicine in Europe.

- Around 1772, Brant became Anglican, a Christian faith. He followed this faith for the rest of his life.

- Besides speaking English fluently, Brant spoke at least three, and possibly all, of the Six Nations' Iroquoian languages.

- Brant was a Freemason, a member of a social and charitable organization.

Honors and Memorials

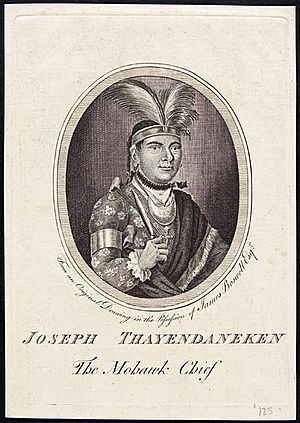

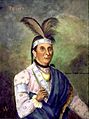

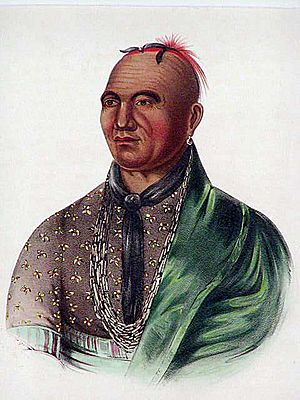

Many artists painted portraits of Brant during his lifetime. Two famous ones show his importance in history:

- George Romney's portrait, painted in 1775–76, is in the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, Ontario.

- The Charles Willson Peale portrait, painted in 1797, is in Philadelphia. Brant chose to wear traditional Mohawk clothing for these formal portraits.

- The Joseph Brant Museum was built in the mid-1800s on land Brant once owned. An Ontario Historical Plaque marks the Brant House's importance.

- The City of Brantford and the County of Brant, Ontario, are named after him. They are located on part of his land grant. The town of Brant, New York was also named for him.

- Joseph Brant Hospital in Burlington, Ontario, is named for him. It is on land he used to own.

- A statue of Brant (from 1886) is in Victoria Square, Brantford.

- The township of Tyendinaga and the Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory are named after his traditional Mohawk name, spelled differently.

- The neighborhood of Tyandaga in Burlington was also named for him.

- Brant is one of 14 important Canadian military figures honored at the Valiants Memorial in Ottawa, Ontario.

- A dormitory and one of the squadrons at the Royal Military College of Canada are named for him.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Joseph Brant para niños

In Spanish: Joseph Brant para niños