Grand River (Ontario) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Grand River |

|

|---|---|

A map of the Grand River's course

|

|

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Ontario |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Main source | Near Dundalk, Ontario 525 m (1,722 ft) |

| River mouth | Lake Erie at Port Maitland 174 m (571 ft) |

| Length | 280 km (170 mi) |

The Grand River is a big river in Southwestern Ontario, Canada. It's also known as French: La Rivière Grand in French and Mohawk: Kenhionhata:tie in Mohawk. Long ago, it was called The River Ouse.

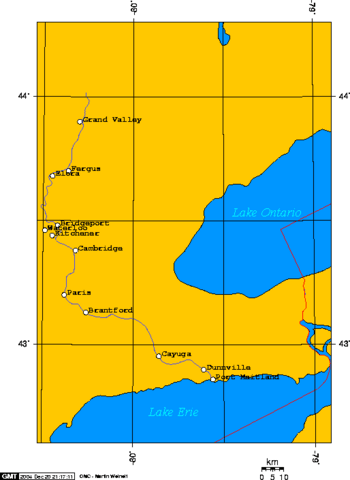

This river starts near Wareham, Ontario. It flows south through many towns. These include Grand Valley, Fergus, Elora, Waterloo, Kitchener, Cambridge, Paris, Brantford, Caledonia, and Cayuga. Finally, it empties into Lake Erie at Port Maitland. A beautiful part of the river is the Gorge and its falls near Elora.

The Grand River is the longest river that stays completely within southern Ontario. It gets so big because its source is close to Georgian Bay (part of Lake Huron). But instead of flowing there, it flows south to Lake Erie. This long journey allows it to collect water from many smaller rivers and creeks.

The river is mostly quiet and easy to get to. This makes it a great place for canoeing. Many conservation areas are along the river. The Grand River Conservation Authority manages these areas. The Grand Valley Trail is a long path, 275 km (171 mi) long. It follows the river's valley from Dundalk to Lake Erie.

The Mohawk name for the Grand River, O:se Kenhionhata:tie, means "Willow River." This is because of the many willow trees in the area. In the 1700s, French settlers called it Grande-Rivière. Later, John Graves Simcoe tried to rename it the Ouse River. He named it after a river near his childhood home in England. But the French name, Grand River, stuck around and is still used today.

Contents

Understanding the Grand River's Watershed

A river's watershed is all the land where water drains into that river. The Grand River watershed includes all the land that feeds into the Grand River. This happens through smaller streams and rivers. Some of these are the Conestogo, Speed, Eramosa, Irvine, and Nith rivers. The Grand River has the largest watershed in Southern Ontario.

This watershed is like a natural area with its own borders. It crosses many town and city lines. It's a special area between Southwestern Ontario and the Golden Horseshoe region. The river starts near Dundalk in the north. It then flows south-south-east.

Luther Marsh is a huge wetland area, about 52 square kilometers (20 square miles). It's on the upper part of the Grand River. It's one of the biggest wetlands inland in southern Ontario. This marsh is home to many animals. It provides habitat for waterfowl like least bittern and black tern. It's also important for amphibians. During bird migrations, it's a key stop for many birds. The Grand River's watershed is very important. Because of this, the Grand River is named a Canadian Heritage River.

The Grand Valley Dam helps control the river's water flow. It's near the village of Belwood. This dam is especially helpful during spring floods. It was finished in 1942. People often call it Shand Dam. This name comes from a local family whose land was used to create the dam's reservoir, Lake Belwood.

Rivers and Creeks Joining the Grand

The Grand River watershed covers about 7,000 square kilometers (2,700 square miles). Many smaller rivers and creeks flow into it. Here are some of them:

- Canagagigue Creek

- Chilligo Creek

- Conestogo River

- Eramosa River

- Fairchild Creek

- Idlewood Creek

- Irvine Creek

- Knob Creek

- Laurel Creek

- McKenzie Creek

- Mill Creek

- Nith River

- Schneider Creek

- Speed River

- Spencer Creek

- Whitemans Creek

The Conestogo River joins the Grand River near Conestogo village. This is just north of Waterloo. The Eramosa River meets the Speed River in Guelph. Then, the Speed River joins the Grand River in Cambridge. The Nith River flows into the Grand River in Paris.

A Look at the Grand River's Past

In the 1500s and 1600s, the Grand River valley was home to the Attawandaron people. They spoke an Iroquoian language. European settlers later called them the "Neutral Nation." This was because they chose not to pick sides between the French and English during their conflicts.

The Wyandot were another Iroquoian-speaking group. They lived northeast of the Grand River valley. They tried to stay independent from their enemies, the Iroquois Confederacy. This was a strong group of five nations from what is now New York state. The Neutral Nation was caught in the middle. They faced hardship for not joining either side.

Most historical stories agree that the Seneca and Mohawk nations of the Iroquois defeated the smaller Neutral tribe in the 1600s. This happened while they were also attacking and weakening the Huron/Wyandot. The Iroquois wanted to control the valuable fur trade with Europeans. During this time, the Iroquois attacked the Jesuit mission at Sainte-Marie among the Hurons. Many Wyandot people and priests were killed there, and the Jesuits left the mission.

Some of the Neutral people who survived moved in 1667. They went to La Prairie (also called Caughnawaga or Kahnawake). This was a Catholic mission settlement south of Montreal. It was mostly home to Mohawk people who had become Catholic and moved north from New York. By 1674, records show groups of Neutral people living there. It's likely that many of their descendants live there today. Later, in wars between Britain and France, the Caughnawaga people often helped the French. The Iroquois League in New York either stayed neutral or helped the British. This made it hard for the Iroquois nations to avoid fighting each other. They managed to avoid major conflict until the American Revolution (1775–83).

Other descendants of the Neutrals might have joined the Mingo. This was a group of different peoples who moved west in the 1720s. They were leaving lands taken by the Iroquois. They settled in what is now Ohio. The Mingo were among the tribes who later fought Americans in the Northwest Indian Wars for the Ohio Valley (1774–95). In the 1840s, many tribes, including the Mingo, were moved to Oklahoma. This was west of the Mississippi River. Today, some descendants of the Neutrals are among the Seneca people in Oklahoma.

After the Neutral tribe was gone, the Iroquois Confederacy used the Grand River Valley for hunting and trapping. Even though the Six Nations (which by then included the Tuscarora) controlled the land, they didn't settle there much. They only had a small presence on the northern and western shores of Lake Ontario.

When French explorers and Coureurs de bois (forest runners) came looking for furs, the Grand River Valley was one of the last parts of southern Ontario to be explored. The French worked closely with Native allies for fur trading. So, they only went where Native people lived. Even after the English took over New France in 1760, the Grand River Valley stayed mostly empty and unexplored.

An explorer's map from 1669 called the river Tinaatuoa or Riviere Rapide. A 1775 map showed it as Urse. This name also appeared on maps from 1708 and 1744. The d’Anville map of 1755 showed the river Tinaatuoa but added "Grande River" at its mouth. Other names in the 1700s were Oswego and Swaogeh. In 1792, Simcoe tried to change the name from Grande Riviere to Ouse. He named it after a river in England. The Thomas Ridout map of 1821 shows "Grand R or Ouse." But Simcoe's attempt failed because "Grand River" had been commonly used for a long time.

The Six Nations of the Grand River

During the American War of Independence, four of the Iroquois Confederacy nations sided with the British. These were the Mohawk, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca. The Tuscarora and Oneida mostly sided with the American colonists. Fighting in the Mohawk Valley was very harsh. It led to massacres and cruel acts on both sides. This made colonists feel very strongly against the Iroquois.

After the war, the British gave away Iroquois land in New York to the new United States. They did this without asking the Iroquois or including them in the talks. The Iroquois were not welcome in the new country. So, the Six Nations leader Joseph Brant asked the British Crown for help. The British had promised to help their allies.

To thank them for their help in the war, the Crown gave the Iroquois land in Upper Canada. Joseph Brant led Mohawk people and families from other Six Nations to Upper Canada. They first settled where Brantford is today. This is where Brant crossed, or 'forded,' the Grand River. It was also called Brant's Town. Not all Six Nations members moved north. Some parts of the old confederacy still live in New York state today. Some are on lands recognized by the government.

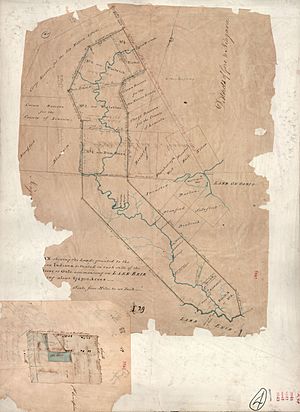

In 1784, the British Crown gave the Six Nations a large area of land. It was called the "Haldimand Tract." This land was "six miles deep from each side of the river." It started at Lake Erie and went all the way to the river's source. Over time, much of this land was sold or lost by the Six Nations.

A part of this land near Caledonia, Ontario is why there was a land dispute in 2006. This was the Caledonia land dispute. The Six Nations made a land claim with the government. The Six Nations reserve south of Brantford, Ontario, is what's left of the Haldimand Tract. In the 1800s, many Anglo-Canadian towns grew along the Grand River. These were on land that used to belong to the Six Nations. Towns like Waterloo, Berlin (now Kitchener), Cambridge, Paris, Brantford, Caledonia, Dunnville, and Port Maitland developed there.

After the American War of Independence, the Crown bought land from the Mississaugas in Upper Canada. They gave this land to Loyalist refugees. This was to make up for property they lost in the colonies. Loyalists from New York, New England, and the South settled here. The Crown hoped they would build new towns and farms. In the 1800s, many new immigrants came to Upper Canada. They came from England, Scotland, Ireland, and Germany looking for chances. Towns were growing all over Southern Ontario. Many settlers wanted the valuable Grand River Valley.

A book from 1846, called a Gazetteer, tells the history of the First Nations in the area: "In 1784, Sir F. Haldimand ... gave the Six Nations and their future generations a piece of land on the Ouse, or Grand River. It was six miles deep on each side of the river, starting at Lake Erie and going to the river's source. This gift was confirmed by a special document from Lieutenant Governor Simcoe, dated January 14, 1793... The land was originally 694,910 acres. But most of this has since been given back to the Crown. The Crown holds it in trust, to be sold for the benefit of these tribes. Some smaller parts have been given to buyers with the Indians' agreement. Or they have been rented out by the chiefs. Even though these leases were not fully legal, the government at the time thought it was fair not to cancel them."

Images for kids

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |