Tuscarora people facts for kids

| Skarù:ręˀ | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| 17,412 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| By 17th century in North Carolina; 21st century: New York, United States and Ontario, Canada, North Carolina. | |

| Languages | |

| English, formerly Tuscarora | |

| Religion | |

| Kai'hwi'io, Kanoh'hon'io, Kahni'kwi'io, Christianity, Longhouse, Handsome Lake, other Indigenous religions | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Haudenosaunee, Meherrin Nation, Nottoway, Coharie, other Iroquoian peoples |

The Tuscarora people (in their own language, Skarù:ręˀ, meaning "hemp gatherers" or "Shirt-Wearing People") are a Native American tribe. Today, members of the Tuscarora tribe live in New York, USA, and Ontario, Canada. They are part of the Iroquoian family, which means they share a similar language and culture with other tribes like the Iroquois Confederacy.

Long ago, before Europeans arrived, the Tuscarora lived around the Great Lakes. Later, they moved south and settled in what is now Eastern Carolina. They were the largest group of Native people in that area. Their villages were along rivers like the Roanoke, Neuse, Tar, and Pamlico. European explorers first met the Tuscarora in the lands that became North Carolina and Virginia.

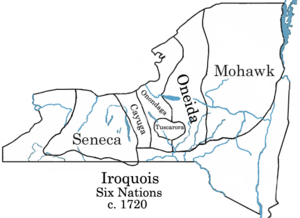

In the early 1700s, the Tuscarora fought a war (the Tuscarora War) against English colonists and their Native allies. After the war, most of the surviving Tuscarora moved north. This journey took about 90 years. They went to Pennsylvania and then to New York. They joined the Iroquois in New York because they shared language and culture. In 1722, the Tuscarora were accepted as the Sixth Nation of the Iroquois Confederacy, also known as the Haudenosaunee.

During the American Revolution, the Tuscarora and the Oneida tribe sided with the American colonists. After the war, the Tuscarora shared land with the Oneida before getting their own reservation. Today, the Tuscarora Nation of New York is officially recognized by the U.S. government.

Some Tuscarora who supported the British in the American Revolution moved to Ontario, Canada. They became part of the Six Nations of the Grand River First Nation. Only the Tuscarora tribes in New York and Ontario are officially recognized by their national governments.

Contents

Tuscarora History

The Tuscarora nation that Europeans met in North Carolina had three main groups:

- Kǎ'tě’nu'ā'kā (also called Katenuaka or Kautanohakau), meaning "People of the Submerged Pine-tree."

- Akawěñtc'ākā (also Akawenteaka or Kauwetseka), meaning "People of the Water."

- Skarū'ren (also Skuarureaka), meaning "Hemp Gatherers," which is where the name Tuscarora comes from.

These groups stayed active even after the tribe moved to New York and Ontario. An early historian, F.W. Hodge, wrote that the Tuscarora in North Carolina lived between the coast and the mountains. He said they had 24 large towns and about 6,000 people.

In the late 1600s and early 1700s, European colonists in North Carolina knew of two main Tuscarora leaders: Chief Tom Blunt in the north and Chief Hancock in the south. Around 1708-1710, estimates said there were between 1,200 and 2,000 Tuscarora warriors. Their total population was likely three to four times that number.

Chief Blunt lived near what is now Bertie County, North Carolina, by the Roanoke River. He got along well with the colonial Blount family and lived peacefully.

Chief Hancock lived closer to New Bern, south of the Pamlico River. He faced more problems because many colonists were moving onto his land. Settlers sometimes raided his villages and kidnapped people to sell them into slavery. The Tuscarora also suffered greatly from European diseases that they had no protection against. Both groups also lost land to the colonists. By 1711, Chief Hancock felt he had to fight back. Chief Tom Blunt did not join him in this war.

The Tuscarora War

The southern Tuscarora joined with other Native groups like the Pamlico and Coree. They attacked settlers in many places on September 22, 1711. This started the Tuscarora War. They targeted farms along the Roanoke, Neuse, and Trent rivers, and the town of Bath. Hundreds of settlers were killed, including important colonial leaders.

Governor Edward Hyde of North Carolina called for help. South Carolina sent 600 militia and 360 Native American allies, led by Col. John Barnwell. In 1712, this force attacked the southern Tuscarora at Fort Narhontes, on the Neuse River. The Tuscarora were badly defeated, with over 300 killed and 100 captured.

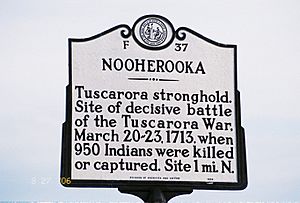

The governor offered Chief Blunt leadership of all Tuscarora if he helped defeat Chief Hancock. Blunt captured Hancock, who was then tried and executed by North Carolina officials. In 1713, the Southern Tuscarora were defeated again at their Fort Neoheroka (also spelled Neherooka). About 900 Tuscarora were killed or captured in this battle.

After this defeat in 1713, about 1,500 Tuscarora fled north to New York to join the Iroquois Confederacy. Another 1,500 found safety in Virginia. While some stayed in Virginia, most of the remaining Tuscarora returned to North Carolina. In 1715, 70 southern Tuscarora warriors went to South Carolina to help colonists fight the Yamasee tribe. These warriors later settled near Port Royal, South Carolina with their families.

Life After the War

Under Tom Blunt's leadership, the Tuscarora who stayed in North Carolina signed a treaty in June 1718. This treaty gave them about 56,000 acres of land on the Roanoke River in Bertie County. This was the area where Chief Blunt and his people lived. Both Virginia and North Carolina recognized Tom Blunt (who took the last name Blount) as "King Tom Blount" of the Tuscarora. They agreed to only consider Tuscarora who followed Blount as friendly. The remaining Southern Tuscarora had to move from their villages on the Pamlico River to villages in Bertie County. In 1722, the Bertie County Reservation, known as "Indian Woods," was officially created.

As more colonists moved in, the Tuscarora at Indian Woods faced many problems. They were treated unfairly, cheated in trade, and their land was taken by settlers. Over the years, the colonial government kept shrinking the Tuscarora land, often in unfair deals.

Many Tuscarora were unhappy with Tom Blount's leadership and decided to leave the reservation. In 1722, about 300 Tuscarora warriors, along with their families, lived at Indian Woods. By 1731, there were only 200 warriors, and by 1755, only 100, with a total population of 301. In 1752, missionaries noted that "many had gone north to live on the Susquehanna" and "others are scattered as the wind scatters smoke." This means many Tuscarora were moving to central-western New York to live with the Oneida and other Iroquois nations.

In 1763 and 1766, more Tuscarora moved north to join other Iroquoian peoples in Pennsylvania and New York. By 1767, only 104 people lived on the reservation in Bertie County. In 1804, the last group to leave North Carolina went to New York. By then, only "10 to 20 Old families" remained at Indian Woods.

In 1802, the remaining Tuscarora at Indian Woods tried to make a treaty with the United States to lease their land. However, the government never approved the treaty, so the North Carolina Tuscarora considered it invalid. In 1831, they sold the remaining rights to their lands. By this time, their 56,000 acres had shrunk to just 2,000 acres.

Even without a reservation, some Tuscarora descendants stayed in southern North Carolina. They married other residents. In 1971, Tuscarora descendants in Robeson County tried to get an accounting of their lands and money owed to them from the unapproved treaty of 1803. Several groups in Robeson County have since organized as Tuscarora. In 2010, they united as the Tuscarora Nation One Fire Council.

Moving North: The Great Migration

The Iroquois Five Nations of New York had already reached the Tuscarora homeland in North Carolina by 1701. They controlled the land in between. When they found a tribe that spoke a similar language, they were happy to welcome their distant relatives. They invited the Tuscarora to join their "Sixth Nation" and move to safer lands in the north.

After the war, around 1713, groups of Tuscarora began leaving North Carolina. They set up a main village in what is now Martinsburg, West Virginia, on a place still called Tuscarora Creek. Another group stopped in Maryland along the Monocacy River around 1719–1721. They were on their way to join the Oneida nation in western New York. After 1730, when many white settlers moved into the Martinsburg area, the Tuscarora continued north to New York. Other Tuscarora groups stayed for a while in the Juniata River valley of Pennsylvania before reaching New York.

Today, in the area from Martinsburg, West Virginia to Berkeley Springs, there are still roads, creeks, and land named after the Tuscarora. This includes a neighborhood in Hedgesville called "The Woods," where street names refer to the Tuscarora. There's also a burial mound recognized as an archaeological site. Records from 1763 show that some Tuscarora did not move to the Iroquois. Instead, they stayed in the Panhandle region and fought alongside Shawnee Chief Cornstalk.

Tuscarora During the American Revolution

During the American Revolutionary War, some Tuscarora and Oneida nations in New York supported the American colonists. Most warriors from the other four Iroquois nations supported Great Britain. Many of them fought in battles across New York. Later in the war, the Tuscarora who supported the British followed Chief Joseph Brant of the Mohawk and other British-allied tribes north to Ontario, Canada. They helped create the reserve of the Six Nations of the Grand River First Nation.

In 1803, the last group of southern Tuscarora moved to New York to join their tribe's reservation in Niagara County. After this, the Tuscarora in New York no longer considered the groups remaining in the south as part of their nation. However, some descendants of these southern groups still identify as Tuscarora and have formed their own bands.

War of 1812 and Modern Challenges

During the War of 1812, on December 19, 1813, the British attacked Lewiston, New York. A group of Tuscarora living in a village above the town fought to protect Americans fleeing the attack. The British were with their allies, the Mohawk, and some American Loyalists pretending to be Mohawk. The American militia ran away, leaving only the Tuscarora. Even though they were outnumbered, they fought to slow down the British, allowing some townspeople to escape. The British burned Lewiston and the Tuscarora village.

The Tuscarora have continued to fight to protect their land in New York. In the mid-1900s, a New York City official named Robert Moses bought 550 acres of the Tuscarora reservation. This land was used for a reservoir for a new hydroelectric power project along the Niagara River. This project, which started in 1962, was the largest in the world at the time. It still provides cheap electricity today.

Tuscarora Language

The Tuscarora language, called Skarure, is part of the northern branch of the Iroquoian languages. Experts have tried to figure out when the Iroquoian-speaking Meherrin and Nottoway tribes separated from the Tuscarora. Before Europeans arrived, the English thought these three tribes were one people. This was because Algonquian natives called them all by the same name, Mangoag. When the English met the Tuscarora and other tribes, they noticed they could use the same interpreters for all of them. This showed their languages were very similar.

The Nottoway language died out in the early 1900s. However, linguists know it was closely related to Tuscarora. The Cheroenhaka (Nottoway) Tribe has been working to bring the Nottoway language back to life. Even though their languages were similar, the three tribes always saw themselves as separate and independent peoples.

Officially Recognized Tuscarora Tribes

- Tuscarora Nation at Lewiston, New York (USA)

- Tuscarora at Six Nations of the Grand River, Ontario, Canada

Tuscarora Groups in North Carolina

Several groups in North Carolina claim Tuscarora descent. They have organized in different ways since the late 1900s. None of these groups are officially recognized by the state or federal government.

Some of these groups include:

- Tuscarora Indian Nation of North Carolina (Robeson County)

- Southern Band Tuscarora Indian Tribe (Windsor, North Carolina)

- Tuscarora Tribe of Indians Maxton (Maxton, North Carolina)

- Tosneoc Tuscarora Community (Wilson County, North Carolina)

- Skaroreh Katenuaka Nation

- Cape Fear Band of Skarure Woccon (mainly in Brunswick, Bladen, Columbus, and Pender Counties, and also South Carolina)

Tuscarora leaders in New York do not agree that any groups in North Carolina are still a tribe with a continuous history. They say that most of the tribe moved north to New York. New York leaders believe that individuals who stayed in North Carolina no longer have tribal status, even if they have Tuscarora ancestors.

Both the New York Tuscarora and the North Carolina groups claim the historic name of the tribe. Since the New York tribe is federally recognized and has been organized as a tribal government for a long time, it is seen as the official continuation of the historic tribe. Members of the North Carolina groups say they are descendants and have a continuous link to the ancient Skarure. Some North Carolina Tuscarora feel that the Tuscarora who left North Carolina abandoned their homelands. They believe both groups should have a relationship with the federal government.

In the 1930s, the Department of Interior examined 209 people in Robeson County. They found that 22 had at least half Native American ancestry, and 18 more were close to that. Today, experts no longer use physical exams to determine ancestry. Each federally recognized tribe decides its own rules for membership. These rules are usually based on proving descent from a list of historical members or from known living members.

In the 1960s, the eight surviving people from the 22 mentioned above, along with their descendants and about 2,000 others in their communities, formed an official Tuscarora political group in Robeson County. On November 12, 1979, the "Tuscarora Tribe of Indians Maxton" was accepted into the National Congress of American Indians.

Different groups of Tuscarora in Robeson County have split since their first organization in the 1960s. They have worked to get state and federal recognition. A request by the Hatteras Tuscarora to the federal government in 1978 was put on hold.

In 1989, a government lawyer ruled that the Lumbee Act of 1956 prevented any Native American groups in Robeson and nearby counties from being considered for federal recognition. This was because the Lumbee leaders had agreed to this rule when the law was passed. This rule was applied to the Lumbee's own request for federal recognition in 1986. One expert, Gerald M. Sider, says that instead of fighting this rule, the Lumbee withdrew their request. This also stopped the Tuscarora requests from being considered.

In 2006, the Skaroreh Katenuaka Nation, also known as the "Tuscarora Nation of Indians of North Carolina," filed a lawsuit for federal recognition. The Skaroreh Katenuaka Nation, the Hatteras Tuscarora, and the Tuscarora Nation of the Carolinas are all based in Robeson County. Their members are closely related.

In May 2010, leaders and people from the different Tuscarora groups in the Robeson County area came together. They formed the Tuscarora Nation One Fire Council (TNOFC). The TNOFC is a temporary, unofficial government. It is based on rules from the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois League) Great Law of Peace. The TNOFC meets weekly. Its members are working to solve problems that have caused divisions among them in the past. The TNOFC has its own membership rules and its members are not part of the state-recognized Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina. Between March 21 and 23, 2013, citizens from both the Tuscarora in New York and North Carolina reunited to mark the 300-year anniversary of the Fort Neoheroka massacre.

Tuscarora Descendants in Oklahoma

Some Tuscarora descendants live in Oklahoma. They are mainly descendants of Tuscarora groups who joined with relocated Iroquois Seneca and Cayuga tribes in Ohio in the early 1800s. These groups became known as Mingo in the Midwest. The Mingo were later forced to move to Indian Territory (now Kansas) and then to Oklahoma. In 1937, their descendants reorganized and were federally recognized as the Seneca-Cayuga Tribe of Oklahoma. This nation lives in the northeast corner of what used to be Indian Territory. A group of Tuscarora also moved to Oberlin, Fremont, and Elmore, Ohio in the mid-1800s from New Bern, North Carolina. They helped with the Underground Railroad.

Famous Tuscarora People

- Wallace "Mad Bear" Anderson (1927–1985), a Native activist.

- David Cusick, an artist and writer.

- Dennis Cusick, a painter.

- Eric Gansworth, a poet and visual artist.

- John Napoleon Brinton Hewitt, a linguist and expert on cultures.

- Henry Berry Lowrie, who led a resistance in North Carolina during and after the American Civil War.

- Frank Mount Pleasant (1884–1937), an athlete.

- Clinton Rickard (1882–1971), a Native activist.

- Alicia Elliott, an author.

Other Iroquoian-Speaking Peoples

See also

In Spanish: Tuscarora para niños

In Spanish: Tuscarora para niños

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |