Expulsion of the Loyalists facts for kids

| Part of the American Revolution and American immigration to Canada |

|

Loyalists demanding protection from Great Britain

|

|

| Participants | Government of the British Empire Government of United States Loyalists (United Empire Loyalist) |

|---|---|

| Outcome | Estimated 88,400 refugees

|

During the American Revolution, some people living in the Thirteen Colonies chose to stay loyal to King George III of Great Britain. These people were called Loyalists. Others, known as Patriots, wanted independence from Britain and supported the Revolution.

Historians believe that about 15 to 20 percent of the white population in the colonies, which was around 500,000 people, were Loyalists. When the war ended with Great Britain losing to the Americans and the French, many active Loyalists felt they were no longer safe or welcome in the new United States. They decided to move to other parts of the British Empire. However, most Loyalists (about 80% to 90%) stayed in the United States and became full citizens.

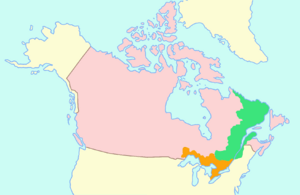

About 60,000 white settlers left the new United States. Most of them, around 33,000, went to Nova Scotia (which included what is now New Brunswick). About 6,600 went to Quebec (which then included modern-day Ontario), and 2,000 went to Prince Edward Island. Some Loyalists, about 5,000 white people, moved to Florida, which was controlled by Spain at the time. They brought about 6,500 enslaved people with them. Around 7,000 white Loyalists and 5,000 free Black Loyalists moved to Britain. Some studies suggest the total number of people who left was closer to 100,000.

The British government offered free land in British North America to the departing Loyalists. Many of these Loyalists were important colonists whose families had lived in America for a long time. Others were newer settlers with fewer ties to the colonies. Patriots often took away their property. Later, around 30,000 more Americans, called 'Late Loyalists', moved to Ontario in the 1790s and early 1800s. They were promised land if they swore loyalty to the King.

Loyalists settled in what was then the Province of Quebec (including modern-day Ontario) and in Nova Scotia (including modern-day New Brunswick). Their arrival brought many English-speaking people to the areas that would become Canada. Many Loyalists from the American South brought their enslaved people with them, as slavery was also legal in Canada. A law in 1790 even promised new immigrants that their enslaved people would remain their property. However, many Black Loyalists were free, having gained their freedom by fighting for the British or joining British forces during the Revolution. The government helped nearly 3,500 free Black Loyalists move to New Brunswick.

Contents

Why Loyalists Left

Loyalists stayed loyal to Britain for several reasons. Some felt a strong connection to the King and did not want to rebel. Others believed that independence should happen peacefully and gradually. For example, Daniel Bliss, who became a Chief Justice in New Brunswick, once said it was "Better to live under one tyrant a thousand miles away, than a thousand tyrants one mile away." This meant he preferred a distant king over many local leaders.

Loyalists Fighting Back

Some Loyalists fought back against the Patriots. Groups like "Butler's Rangers" were formed. John Butler was a wealthy landowner who did not agree with the idea of independence. During the war, he created a guerrilla force. This group attacked the American Army's supply lines, tried to discourage settlers, and fought against Patriot groups.

Attacks on Loyalists

Loyalists faced harsh treatment during the American Revolution. Some of this was legal, but much of it came from angry mobs. Patriots did not tolerate Loyalists who actively supported the King.

British officials were often the first targets of these mobs. In 1765, during protests against the Stamp Act, large crowds in Boston attacked and destroyed the homes of officials like Andrew Oliver and Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson. The owners barely escaped with their lives. In 1770, a mob threw snowballs at British troops, leading the soldiers to fire and kill five people in what became known as the Boston Massacre. In 1773, during the famous Boston Tea Party, Bostonians dressed as Native Americans threw tea into Boston Harbor to protest the Tea Act. No one was hurt, but the tea was ruined. In response, the British Parliament passed the Intolerable Acts. These laws took away Massachusetts's right to govern itself and sent General Thomas Gage to rule the province.

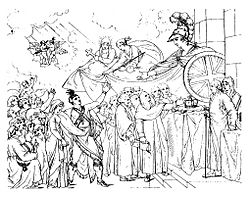

The anger of the Patriots spread throughout the 13 colonies. In New York, mobs destroyed printing presses that published pro-British writings. They also broke windows, stole property, and destroyed belongings. A common punishment for Loyalists was "tarring and feathering" or "riding the rail". These were painful and humiliating ways to punish those who supported the King.

After the Yorktown in 1781, the British only controlled New York City. This city became the main place where Loyalists left America. The British Army stayed there until November 1783.

Many Loyalists who left America had to abandon a lot of their property. The British government tried to give them some money and asked the U.S. to return the rest. This issue was discussed during the Jay Treaty negotiations in 1794. The U.S. government advised the states to give back property, but it was not always done. Even today, some descendants of Loyalists still claim rights to their ancestors' property in the United States.

Where Loyalists Settled

Great Britain

Some of the wealthiest and most important Loyalists moved to Britain. Loyalists from the southern colonies, often with their enslaved people, went to the West Indies and the Bahamas.

About 6,000 Loyalists moved to London or other parts of Britain. Many had been important people in America, but in Britain, they often felt like outsiders. It was hard for them to find good jobs. Only 315 were given government pensions. Many of them advised other Loyalists still in the United States to stay there rather than move to Britain. Some even returned to the United States later.

British North America

Many Loyalist refugees settled in Canada after losing their homes and safety during the Revolution. These Loyalists, whose families had helped build America, left to create a new nation in Canada. The motto of New Brunswick, which was created for Loyalist settlement, became "Hope Restored."

Loyalist refugees, later called United Empire Loyalists, began leaving at the end of the war as soon as they could find transport. They lost a lot of property and wealth. An estimated 85,000 people left the new United States, which was about 2% of the total American population. About 61,000 were white (and had 17,000 enslaved people), and 8,000 were free Black people. Of the white Loyalists, 42,000 went to Canada, 7,000 to Britain, and 12,000 to the Caribbean.

After the Revolution ended and the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783, Loyalist soldiers and civilians were moved from New York. They were resettled in other British colonies, especially in what would become Canada. Nova Scotia and New Brunswick received about 33,000 Loyalist refugees. Prince Edward Island received 2,000. Quebec (including modern-day Ontario) received about 10,000 refugees, including 6,600 white Loyalists and several thousand Iroquois from New York State. Some Loyalists found it hard to settle successfully in British North America, especially in Nova Scotia. Many eventually returned to the United States or moved to Ontario. Many in Canada kept in touch with their relatives in the United States and traded across the border.

Thousands of Iroquois and other Native Americans who supported the British were forced to leave New York and other states. They resettled in Canada. The descendants of one Iroquois group, led by Joseph Brant, settled at Six Nations of the Grand River. This is now the most populated First Nations reserve in Canada. Smaller groups of Iroquois settled near the Bay of Quinte in Ontario and on the Akwesasne Reserve in Quebec.

The government settled many Black Loyalists in Nova Scotia. However, they did not receive enough support when they arrived. The government was slow to survey their land, which meant they could not settle. They also received smaller land grants in less convenient places than white settlers in Nova Scotia. They also faced discrimination from some white settlers, especially when competing for jobs and fair pay. When Great Britain created the colony of Sierra Leone in Africa, about one-third of the Black Loyalists moved there. They hoped to have self-government and established the city of Freetown.

Changes in Quebec

In 1778, Frederick Haldimand became the governor of Quebec, taking over from Guy Carleton. Haldimand, like previous governors, respected the French-speaking Canadiens and tried to keep English merchants from causing problems.

The arrival of 10,000 Loyalists in Quebec in 1784 upset this balance. The growing number of English-speaking people demanded more recognition from the government. To bring back stability, King George III sent Carleton back to Quebec.

Quebec changed a lot in ten years. What worked in 1774 would not work in 1784. There were simply too many English-speaking people who did not want to compromise with the 145,000 Canadiens or the governor. A new approach was needed.

Dividing the Province of Quebec

Loyalists soon asked the government to let them use the British legal system they were used to. To solve this, the Province of Quebec was divided. This created Upper Canada for most Loyalists, where they could live under British laws. The French-speaking people of Lower Canada could keep their French civil law and Catholic religion.

The authorities believed that the two groups could not live together easily. So, Governor Haldimand, following Carleton's idea, offered free land on the northern shore of Lake Ontario to Loyalists who swore loyalty to George III. Loyalists received land grants of 200 acres (81 hectares) per person. This plan aimed to keep French and English speakers separate. So, in 1791, the Province of Quebec was divided into Lower Canada and Upper Canada, each with its own government.

Dividing Nova Scotia

Fourteen thousand Loyalists created a new settlement along the Saint John River. Soon after establishing Saint John, these Loyalists asked for their own colony. In 1784, Great Britain divided Nova Scotia into two parts: New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Colonel Thomas Carleton, Guy Carleton's younger brother, became New Brunswick's first lieutenant-governor. He held this position for 30 years.

|

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |