Thomas Gage facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

General

Thomas Gage

|

|

|---|---|

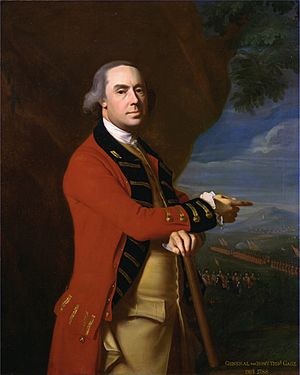

Portrait by John Singleton Copley, c. 1768

|

|

| 13th Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay | |

| In office 13 May 1774 – 11 October 1775 |

|

| Monarch | George III |

| Preceded by | Thomas Hutchinson |

| Succeeded by | Governor's Council (acting) John Hancock (as Governor of Massachusetts) |

| Commander-in-Chief, North America | |

| In office September 1763 – June 1775 |

|

| Monarch | George III |

| Preceded by | Jeffery Amherst |

| Succeeded by | Frederick Haldimand |

| Military Governor of Quebec | |

| In office 1760–1763 |

|

| Preceded by | François-Pierre Rigaud de Vaudreuil |

| Succeeded by | Ralph Burton |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 10 March 1718/19 Firle, Sussex, England |

| Died | 2 April 1787 (aged 67–68) Portland Place, London, England |

| Spouse | |

| Profession | Military officer, official |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | British Army |

| Years of service | 1741–1775 1781–1782 |

| Rank | General |

| Commands | 80th Regiment of Light-Armed Foot Military governor of Montreal Commander-in-Chief, North America |

| Battles/wars | |

General Thomas Gage (born March 10, 1719 – died April 2, 1787) was a British Army general and government official. He is most famous for his many years of service in North America. This included his role as the British commander-in-chief at the start of the American Revolution.

Gage was born into a noble family in England. He joined the military and fought in the French and Indian War. During this war, he even served alongside George Washington, who would later become his opponent. After the city of Montreal was captured in 1760, Gage became its military governor. He was known for being a good administrator.

From 1763 to 1775, he was the commander-in-chief of British forces in North America. He led the British response to Pontiac's War in 1763. In 1774, he was also made military governor of Massachusetts Bay. He was told to enforce the Intolerable Acts, which punished Massachusetts for the Boston Tea Party.

In April 1775, Gage tried to take military supplies from American militias. This led to the Battles of Lexington and Concord, which started the American Revolutionary War. After the costly victory at the Battle of Bunker Hill in June, he was replaced by General William Howe. Gage then returned to Great Britain in October 1775.

Contents

Early Life and Military Career

Thomas Gage was born on March 10, 1719, in Firle, England. His family had lived there since the 1400s. His father, Thomas Gage, was an important nobleman.

In 1728, Gage started attending the famous Westminster School. There, he met people who would become important figures later on. These included John Burgoyne and George Germain.

After school, Gage joined the British Army. He became an ensign in 1741. He was promoted to captain in 1743. He fought in the War of the Austrian Succession in Europe. He also served in the Second Jacobite Uprising in Scotland. This included the Battle of Culloden in 1746.

In 1748, he became a major and later a lieutenant colonel in 1751. Gage was a popular person in the army. He made important friends, like Lord Barrington and Jeffery Amherst. These connections helped him later in his career.

French and Indian War Service

In 1755, Gage's regiment was sent to North America. They were part of General Edward Braddock's expedition. Their goal was to remove French forces from the Ohio Country. This area was claimed by both the French and British.

During the Battle of the Monongahela, Gage's regiment was at the front. They met French and Native American fighters. General Braddock was badly wounded in this battle. George Washington showed great bravery in leading the retreat. Gage was also slightly wounded.

After this battle, Gage was not given permanent command of his regiment. Some people blamed him for the defeat. Gage and Washington remained somewhat friendly for a few years. However, by 1770, Washington openly criticized Gage's actions in America.

Creating Light Infantry Units

In 1756, Gage was part of a failed mission to resupply Fort Oswego. The fort fell to the French before they could reach it. The next year, he was sent to Halifax.

In December 1757, Gage suggested creating a new type of army unit. He wanted a regiment of light infantry. These soldiers would be better at fighting in forests. His idea was approved. Gage then recruited soldiers for the new 80th Regiment of Light-Armed Foot. This was the first light-armed regiment in the British army.

While recruiting, he met Margaret Kemble. She was from a well-known family in New Jersey. They got married on December 8, 1758.

Gage's new regiment fought in the Battle of Carillon. This was a terrible defeat for the British. Gage was wounded again in this battle. In 1759, he was promoted to brigadier general. This promotion was largely due to his brother's political efforts.

Montreal's Military Governor

After the French surrendered Montreal in 1760, Gage was named its military governor. This job involved managing the city and the military occupation. He also had to deal with legal issues and trade with Native American groups.

His wife, Margaret, joined him in Montreal. Their first two children, Harry and Maria Theresa, were born there. In 1761, Gage was promoted to major general.

Gage was seen as a fair leader. He respected people's lives and property. However, he did not trust the French landowners or the Catholic clergy. After the Treaty of Paris ended the war in 1763, Gage wanted a new job. He said he was "very much [tired] of this cursed Climate."

In October 1763, he received good news. He would become the acting commander-in-chief of North America. He took over this role in New York on November 17, 1763. His new job included dealing with Pontiac's War.

Commander-in-Chief in North America

Pontiac's Rebellion

After the British took over New France, General Amherst made some bad decisions. He had little respect for Native American people. He stopped selling them ammunition. This, along with British expansion, caused many tribes to rebel.

In May 1763, under the leadership of Pontiac, they attacked British forts. They drove the British out of some forts and scared settlers.

Gage wanted to end the conflict peacefully. He sent military expeditions and ordered Sir William Johnson to negotiate. Johnson made a treaty in 1764 with some tribes. The conflict finally ended when Pontiac signed a formal treaty in July 1766.

Securing His Position

In 1764, Gage's appointment as commander-in-chief became permanent. He was promoted to lieutenant general in 1771.

Gage spent most of his time in New York City. This was the most powerful position in British America. He had to manage a huge territory. The Gage family enjoyed their life in New York and were active in society.

Gage was careful with public money. However, he did help his family and friends get good positions. This was a common practice at the time. He sent all his children to school in England.

Growing Tensions in the Colonies

During Gage's time as commander, political tensions grew in the American colonies. He began moving troops from the frontier to cities like New York and Boston. As more soldiers were in cities, they needed places to live.

Parliament passed the Quartering Act of 1765. This law allowed British troops to stay in empty houses and barns. It did not allow them to stay in private homes.

Gage believed that the unrest after the Stamp Act was caused by a few powerful people in Boston. In 1768, he suggested sending two regiments to occupy Boston. This made the city even angrier. The soldiers' presence led to the Boston Massacre in 1770.

Later, Gage changed his mind. He thought that democracy was a big threat. He believed that colonists moving inland and using town meetings for local government were dangerous. He wrote in 1772 that "democracy is too prevalent in America." He thought town meetings should be stopped. He also suggested limiting colonization to coastal areas where British rule could be enforced.

Governor of Massachusetts Bay

Gage returned to Britain with his family in June 1773. He missed the Boston Tea Party in December. The British Parliament reacted to the Tea Party with harsh laws against Massachusetts. These were called the Intolerable Acts by the colonists. Some of these laws, like moving political trials to England, were Gage's ideas.

Because of his military experience, Gage was seen as the best person to handle the growing crisis. He was also popular in both Britain and America.

In early 1774, Gage was appointed military governor of Massachusetts. He arrived in Boston on May 13, 1774. At first, Bostonians were happy to see him. But their feelings quickly changed as he began to enforce the new laws.

The Boston Port Act closed the port, causing many people to lose their jobs. The Massachusetts Government Act took away the assembly's right to choose members of the Governor's Council. Gage dissolved the assembly in June 1774. He found out they were sending delegates to the Continental Congress.

Gage tried to influence political leaders like Benjamin Church and Samuel Adams. He succeeded with Church, who secretly gave him information about rebel leaders. But Adams and other rebel leaders could not be swayed.

In September 1774, Gage moved all his troops to Boston. He also tried to take away military supplies. In September 1774, he ordered a mission to remove gunpowder from a storage building in Somerville. This caused a huge reaction called the Powder Alarm. Thousands of militiamen marched towards Cambridge, Massachusetts.

This show of force by the colonists made Gage more careful. The quick response was thanks to Paul Revere and the Sons of Liberty. They watched Gage's actions closely and warned others. A Committee of Safety was also set up to alert local militias if Gage sent troops out of Boston.

Gage was criticized for allowing groups like the Sons of Liberty to exist. One of his officers said, "The general's great lenity and moderation serve only to make them [the colonists] more daring and insolent." Gage himself wrote that if force was needed, it had to be a large one. He believed small numbers would encourage resistance.

American Revolutionary War Begins

On April 14, 1775, Gage received orders from London. He was told to take strong action against the American Patriots. He had information that the militia was storing weapons in Concord, Massachusetts. So, on the night of April 18, he sent British soldiers to confiscate them.

A short fight in Lexington scattered the colonial militia there. But in Concord, a part of the British force was defeated by a stronger colonial militia. As the British left Concord, colonial militias attacked them all the way back to Charlestown. The Battles of Lexington and Concord resulted in 273 British casualties and 93 American casualties.

The British plan to go to Lexington and Concord was supposed to be a secret. But Sons of Liberty leader Joseph Warren found out. He sent Paul Revere and William Dawes to warn the colonists. This led to the battles and started the American Revolutionary War. Some evidence suggests Gage's wife, Margaret Kemble Gage, who was American, might have given this information to Warren.

After Lexington and Concord, thousands of colonial militia surrounded Boston. This began the Siege of Boston. At first, about 4,000 British soldiers were trapped in the city. On May 25, 4,500 more British soldiers arrived. Three more generals also came: William Howe, John Burgoyne, and Henry Clinton.

On June 14, Gage issued a statement. It offered a pardon to anyone loyal to the British Crown. However, John Hancock and Samuel Adams were not included. Gage and the new generals planned to break the siege. They would attack Dorchester Heights and then the rebel camp at Roxbury. Then they would seize the hills on the Charlestown peninsula, including Breed's Hill and Bunker Hill.

The colonists learned of these plans. On the night of June 16-17, they fortified Breed's Hill. On June 17, 1775, British forces under General Howe attacked. This was the Battle of Bunker Hill. It was a very costly victory for the British. They won but suffered over 1,000 casualties. The siege did not change much. General Henry Clinton called it "a dear bought victory, another such would have ruined us."

Return to Great Britain

On June 25, 1775, Gage sent a report to Great Britain about the Battle of Bunker Hill. Three days after his report arrived, he was ordered to return home. William Howe replaced him. Gage received the order on September 26 and sailed for England on October 11.

King George III wanted to reward Gage for his service. Gage kept his title as governor of Massachusetts.

When the Gages returned to England, they settled in London. Some people criticized Gage harshly for his failures. One person wrote that Gage had "run his race of glory." Others were kinder. New Hampshire Governor Benning Wentworth called him "a good and wise man... surrounded by difficulties."

Gage was briefly called back to duty in April 1781. He helped organize troops for a possible French invasion. In 1782, he became commander of the 17th Light Dragoons. He was promoted to full general on November 20, 1782.

Later Years and Legacy

As the war ended in the mid-1780s, Gage's military activities slowed down. He supported Loyalists who lost their property when they left the colonies. He died in London on April 2, 1787. He was buried in his family's plot in Firle.

His wife lived almost 37 years longer than him. His son Henry inherited the family title. He became one of the wealthiest men in England. His youngest son, William Hall Gage, became an admiral in the Royal Navy. All three of his daughters married into well-known families.

Gagetown, New Brunswick in Canada was named in his honor. The Canadian Forces base CFB Gagetown also carries his name.

In 1792, the Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, John Graves Simcoe, named a group of islands in the St. Lawrence River after generals from the Conquest of Canada. These included Wolfe Island, Amherst Island, Howe Island, Carleton Island, and Gage Island. Gage Island is now known as Simcoe Island.

Images for kids

-

A 1776 artist's rendition of Robert Rogers. No real likeness of him was ever made from life.

-

An artistic interpretation of Chief Pontiac by John Mix Stanley. No authentic images of the chief are known to exist.

-

Miniature of Gage by Jeremiah Meyer, R.A., c. 1775.

See also

In Spanish: Thomas Gage para niños

In Spanish: Thomas Gage para niños

- Viscount Gage

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |