Conquest of New France (1758–1760) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Conquest of New France |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Seven Years' War | |||||||

Depiction of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759, a decisive British victory that led to the British occupation of Quebec City |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| James Wolfe † Jeffrey Amherst James Murray William Haviland |

Louis-Joseph de Montcalm † François de Lévis Marquis de Vaudreuil |

||||||

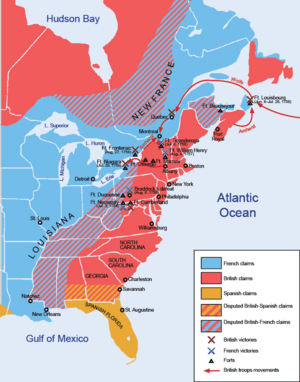

The Conquest of New France (also known as La Conquête in French) was when Great Britain took control of New France during the Seven Years' War (1756-1763). This military takeover started with British attacks in 1758. It ended in 1760 when the area was placed under British military rule until 1763. Britain officially gained Canada with the Treaty of Paris in 1763. This treaty also ended the Seven Years' War.

The term "Conquest" is often used to talk about how this event affected the 70,000 French people living there. It also looks at how it impacted the First Nations (Indigenous peoples). People still debate how Britain treated the French population and what the long-term effects were.

Why the War Started

The Conquest was the last part of many fights between Britain and France over their colonies in North America. In the years before the Seven Years' War, both countries became more interested in their North American lands. This led to a lot of tension between them. British America became a very profitable place to sell goods in the early 1700s. This made it very important to British leaders. They wanted to expand their colonies and didn't want France's land claims to stop them.

France, on the other hand, didn't see its colonies as a big money-maker. Many French leaders thought the colony cost too much. They believed its main value was strategic, meaning it was important for military reasons. France was worried that Britain's strong navy could threaten its rich colonies in the Caribbean.

Both London and Versailles (the French government) often overlooked the fact that these lands were already home to many Indigenous groups. These groups had their own long history of fighting each other. Each group wanted a strong ally who could provide good weapons and other useful items. Alliances were tricky. The French often had better relationships with Indigenous groups, mostly because of the fur trade. The British could offer more generous land treaties and weapons. Even before the war officially began, violence was always a risk in areas where French and English interests overlapped.

Who Was Fighting

New France always had fewer people than the thirteen American colonies of British America. When the fighting began, New France had about 80,000 white settlers, with 55,000 of them in Canada. In contrast, the Thirteen Colonies had 1,160,000 white settlers and 300,000 Black people (both free and enslaved).

However, the number of professional soldiers at the start of the war was more even. In 1755, New France had 3,500 professional soldiers. The Thirteen Colonies had about 1,500 to 2,000 career soldiers from two Irish regiments. They also had two regiments of conscripts (people forced to join the army) from New England. So, the armies on land were somewhat equal at first. At sea, Britain had a huge advantage. In 1755, Britain had 90 warships, while France had only 50. This difference grew over time. This control of the seas allowed Britain to send many more soldiers and supplies to its North American colonies.

The British Takeover

What became known as "The Conquest" started in 1758. At this time, British leader William Pitt decided to greatly increase military efforts in North America. At first, it was not clear if they would actually succeed in taking over all of Canada.

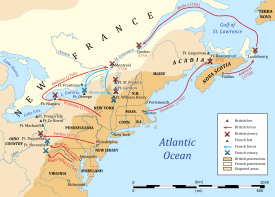

Louisbourg Falls

In July 1758, a British force led by Major-General Jeffery Amherst successfully captured the Fortress Port of Louisbourg. This fortress was in the French colony of Île Royale. After the British Navy brought the army to Ile Royale, the siege began. The siege of Louisbourg was the first big battle and the first major British victory of the Conquest. The siege lasted eight weeks, and the French surrendered on July 26, 1758.

After winning at Louisbourg, Amherst planned three attacks for the next year to finally push the French out of New France. Major General Jeffery Amherst would lead one force from Albany north toward Fort Carillon and then Montreal. A second force would attack Fort Duquesne, which was important because it was where the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers met to form the Ohio River. The French had claimed the Ohio River Valley, calling it "la Belle Rivière."

First Quebec Campaign

The third attack was given to General Wolfe. His job was to capture the fortress city of Quebec. Admiral Saunders was in charge of getting the British forces to Quebec and helping Wolfe. When they arrived, the army set up camp five kilometers from Quebec City on Île d'Orléans. Many French people had already left this island after hearing about Louisbourg. After the British camp was set up, Wolfe ordered his artillery (cannons) to start firing at Quebec City. Even though the constant bombing hurt people's spirits, it wasn't a real military threat to the French.

From the start, Wolfe knew that British success depended on getting the French army out of their forts and into a big battle. The main French commander, Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, was always careful not to commit his troops to one big attack. Montcalm believed the British would eventually run out of supplies or be defeated by Canada's harsh winter. So, his plan was mainly to defend. As a result, French counterattacks were often scattered and sometimes carried out only by untrained civilian volunteers.

At first, and all through the summer, everyone focused on the area east of Quebec City. Louis-Joseph de Montcalm-Grozon, marquis de Montcalm de Saint-Veran, was a master of defense and secured the city's eastern side. By August 1759, both sides (especially the British) were tired from a year of battles. Wolfe still hadn't made much progress. Knowing that the British campaign was almost over, he gathered his remaining troops and resources for one last attack. Wolfe was sure his success would come from the east, but his officers suggested attacking from the west. Surprise was key.

Wolfe landed his troops on the north shore, west of Quebec City. They climbed the steep cliffs in the early morning hours of September 13. The hardest part of this plan was landing 5,000 troops and supplies at night from boats in a strong river. With tough training and skilled naval support, this was done between 4 AM and 7 AM. The first troops to reach the top of the cliffs secured a spot by tricking and then overpowering the small guard. By the time the French realized the British were near the city gates, they had to charge the English in the European style. They marched in columns and ranks across the open field known as the Plains of Abraham.

Wolfe spread his troops across the whole battlefield and protected his sides. This meant he didn't use the usual three-deep line of soldiers. Instead, he had his troops in a line two soldiers deep. He told them to load their muskets with two balls. He then ordered them to hold their fire until the French were only 30 paces away. This would make their shot very powerful. Realizing his troops were vulnerable, Wolfe had them lie on the ground during the first part of the French attack.

Montcalm was not ready for this attack from the west. All summer, everyone had focused on the Beauport defense east of the city. Montcalm had placed a small guard along the western approaches. But there was no sign that the British would try to land along the rushing river shore and have an army climb the cliffs. He believed he had enough forces in the west to stop any British attempt, and the British never gave any hint that they might do this. Now that the threat was real, Montcalm quickly moved his troops. Regular soldiers were in the center, with militia and Indigenous allies on the sides. Montcalm wanted to defeat the British before they could get a strong position. After a short cannon attack, he ordered his three columns forward. Because the ground was rough, his troops couldn't keep their column shape, and their front looked like a messy group of men. When the order to fire was given, the French shots were not effective. Suddenly, they suffered a terrible result. The first British volley (a group of shots fired at once) was devastating. Now the British began to move forward, reloading their weapons. The second British volley hit before the shock of the first one had worn off. The French soldiers who survived only wanted to find a safe place to hide. The battle was won.

By the time the French fled, General Wolfe was dead. He had been wounded first when a ball hit his wrist while he was giving final orders. He was able to continue. He stood in line with his beloved Grenadiers. Just as he was about to give the order to fire, he was hit two more times, once in the stomach and once in the chest. The men next to him carried him a short distance back. When asked if he wanted the surgeon, he said no, "all is over with me." When told that the French were running away, he gave orders to try and stop them from escaping across the Saint-Charles River. His last words were, "Now, God be praised, I die contented."

As the French retreated, General Montcalm, on his horse, tried to get his troops back in order. He suddenly slumped in his saddle. He had been hit in the back by a musket ball. A couple of officers helped him limp into the city. He was taken to a surgeon, who said Montcalm would not live through the night. He died at sunrise on September 14, 1759. The battle was over, but the fate of Quebec was not certain until the next year. The British forced the city to surrender and took control within a week. However, the Navy had to return to England before the river froze. The British had a very difficult winter, mainly because they had destroyed the city during months of siege and bombing. Meanwhile, the French were much more comfortable planning a spring counterattack from warm buildings in Montreal.

Second Quebec Campaign

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham was a big victory, but it didn't immediately guarantee British success. Also, Montcalm's death was a huge blow to French morale, but it wasn't the only reason for their defeat. The Conquest was more than just two men and one battle. Historians like Matthew Ward say that the British victory actually depended more on the safe arrival of the British relief fleet in May 1760. After the Plains of Abraham, the French army regrouped in Montreal under the command of François Gaston de Lévis. The British, who didn't have enough supplies, had to survive a harsh Canadian winter in a city they had already damaged. After the battle, on September 18, 1759, the Articles of Capitulation of Quebec were signed between British and French leaders.

In April 1760, the French army (now based in Montreal) made a final attempt to take back Quebec City. They attacked the British at Sainte-Foy, just outside Quebec City's walls. The French won this battle in terms of how many soldiers were lost. However, the French were unable to retake Quebec City and had to retreat to Montreal.

Montreal Campaign

After the failed siege of Quebec, the British commanders wanted to finish the Conquest. In July, about 18,000 British soldiers, led by Jeffery Amherst, marched on Montreal from three different directions. One force came with Amherst from Lake Ontario. Another came with James Murray from Québec. The third came with William Haviland from Fort Crown Point.

These three attacks lasted almost two months and completely removed all French forts and positions. Many Canadians left the French army or gave up their weapons to the British. The Indigenous allies of the French sought peace and neutrality. By September 6, all three British forces had joined up and surrounded Montreal. Lévis tried to negotiate a surrender with "Honours of War" (special terms for a defeated army), but Amherst refused. However, Pierre François de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnal, the French civilian Governor, convinced Lévis to surrender to avoid another bloody fight.

On September 8, 1760, Lévis and Vaudreuil surrendered the entire French colony of Canada. With the surrender of Montreal, the British had effectively won the war. The exact details of the Conquest still needed to be worked out between England and France. So, the region was placed under military rule while waiting for the results in Europe. During this time, following the "rules of war" of that era, Britain promised the 60,000 to 70,000 French-speaking inhabitants that they would not be forced to leave. They also promised that their property would not be taken, they would have freedom of religion, the right to move to France, and fair treatment in the fur trade.

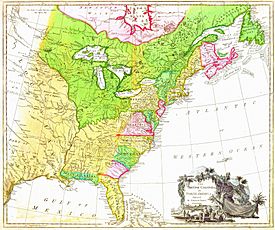

Treaty of Paris – 1763

The final details were decided by British and French diplomats in Europe, far from the battlefields. In February 1763, the Treaty of Paris officially made the northern part of New France (including Canada and some lands to the south and west) a British colony. Canada was given to the British without much protest. As historian I.K. Steele points out, the Conquest of Canada was only one part of the Seven Years' War. France was willing to give up Canada peacefully in exchange for its more profitable colonies in the West Indies, especially Guadeloupe. Also, the agreement allowed France to keep the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon off the coast of Newfoundland. This ensured they could still access the valuable Atlantic fisheries.

What Happened Next

Britain decided to keep Canada for several reasons. One reason was to calm the French, who were still a big threat to British interests, even after losing the war. This meant giving up either Canada or the French Caribbean islands. In the end, they decided to give up the French sugar islands, even though they were much more valuable than the North American French colonies. This was partly because taking the French Antilles (Caribbean islands) would have been a big blow to French pride. The French Monarchy might not have accepted it, which would have made a quick peace deal harder. More importantly, keeping Canada was seen as a way to make Britain's Empire in North America safer.

The Quebec Act

The Quebec Act was passed on June 15, 1774. It expanded the colony's borders, giving control over the fur trade region near Montreal to the Province of Quebec. It also gave Canadiens (French Canadians) freedom to practice their religion. It confirmed that French civil law (Coutume de Paris) would continue to be used for civil matters, while English law would be used for criminal matters. The act also decided not to create a legislative assembly, recognizing that an earlier attempt had failed in Quebec.

How People Adapted

Historian Donald Fyson describes the changes after the British took over as a system of "mutual adaptations." This means that both the conquered French people and the British conquerors had to adjust to each other. It wasn't just the British forcing their ways on the French. Instead, daily life and systems show how both sides made practical changes to get along.

Religious Changes

One example of this adaptation was the status of Catholics in the colony's legal system. After the first civil government of Quebec was set up in 1763, official rules said that all British laws that barred Catholics from holding paid government jobs should be enforced. This included the 1558 Act of Supremacy. In October 1764, a Quebec grand jury even complained about Catholic jurors. They called it a "violation of our most sacred Laws and Libertys."

However, despite these strict rules, the legal system had some flexibility. Governor Murray was able to make exceptions to deal with real-life situations. The wording of the 1764 complaint only excluded "papist[s] or popish recusant convict[s]," not all Catholics. This gave colonial leaders room to staff the government. There were very few Protestant men in the colony (only 200 in 1763, growing to 700 by 1775). This meant that governors like Carleton and Murray had to hire Canadien people to work in the government. The changing legal definition of Catholicism in Quebec shows that it wasn't just British culture taking over. Instead, it was about both sides adapting to the local situation and challenges.

Political Changes

The political side of the colony under early British rule also shows how both sides adapted. Not only did the Canadiens have to get used to new power structures, but British officials and settlers also had to adjust to new ways of governing. At the highest level, the British kept authoritarian political structures, similar to the French system. Governor Murray led a "paternalistic, intrusive and controlling government." This was much like the French way of ruling. In this system, British settlers had to adapt to a lack of parliamentary institutions (like a parliament). For example, many conflicts broke out between British merchants and colonial leaders. This helps explain why many British merchants supported the American revolutionaries in 1775-1776.

Land and Symbols

The British continued to use French structures in deeper ways, including how land was organized and what symbols were used. Instead of changing how property was divided into the traditional English township system, the British used the existing land organization. The continued use of the French-Canadian parish as the basis for how the colony's territory was managed shows that the British adapted to existing land ownership methods instead of forcing their own. The use of space and political symbols was also important in the decision to keep using places of power that were previously French. For example, the Chateau St-Louis, the Jesuit college, and the Recollet church kept their administrative roles under British rule. This was quite strange for British civilians who found themselves being tried in Catholic buildings.

Economic Effects

The economic results of the Conquest of New France are best understood by looking at the larger economic systems of Britain and France at the time. When the Seven Years' War ended, both countries faced very different economic situations.

Impact on Britain

During the war, Britain's expansion and strong navy helped its trade and production. Military spending, especially on building ships and weapons, boosted the metal-working industry. The British textile industry also grew because of the need for uniforms. Overall, during the war, exports went up 14% and imports went up 8%. However, after the war, Britain faced about two decades of economic slowdown. The government had borrowed a lot of money to fight the war. Annual spending rose from a low of 6-7 million pounds in peacetime to 21 million during the conflict.

The land gained in North America (Canada) was not very profitable itself. Its main value was that it made other British colonies in the Americas safer. The fur trade, which was important, had suffered because of recent conflicts like Pontiac's War. Because Canada wasn't making much money, and because of other issues, the British had few ways to pay off their war debts except by raising taxes on their other colonies. The taxes put in place after the Seven Years' War contributed to the growing frustrations that led to the American Revolution. Also, taking over Quebec removed the reason for stopping the Thirteen Colonies from expanding westward (the French threat). Without a good reason to stop western settlement, the British decision to call western lands "Indian land" frustrated the colonists. This made them complain about the British government's control. In short, the Conquest and the Seven Years' War were not very profitable for the British. They brought little economic gain and instead helped lead to the loss of a profitable part of their empire.

Impact on France

France's situation was quite different. During the war, French trade across the Atlantic suffered because of reduced trade with its Caribbean colonies. Exports dropped by 75% and imports by 83%. French industry didn't benefit as much from wartime spending, partly because its ships couldn't compete with the British at sea. The 1763 Traité de Paris (Treaty of Paris) confirmed that Britain owned Quebec, but France kept its Caribbean colonies and Newfoundland fisheries. This arrangement meant that losing the war had little economic impact on France. It had gotten rid of territory it considered a burden, while keeping the parts of its empire that were key to its wealth. Also, because French economic activity had slowed during the war, peace meant a revival of French trade. The year after the peace agreement, sugar production from the Caribbean went from 46 million livres (French money) in 1753 to 63 million. By 1770, the sugar trade was making 89 million livres; by 1777, it was 155 million livres.

Impact on Canada

For the local economy in Canada, historian Fernand Ouellet found that after the direct damage from the war was fixed, the economic impact was small. In fact, the British takeover had a clearly positive effect on the economy. For example, the conquest of Canada led to a logging trade that didn't exist under French rule. From 6,000 barrels of pine per year, the colony under British rule increased production to 64,000 barrels by 1809. Also, the British encouraged immigration, which was needed for Canada's economic growth in the 19th century. In 1769, Canadian exports were worth 127,000 pounds sterling. By 1850, they had grown to 2,800,000 pounds sterling.

History and Memory

The Conquest is a very important and debated topic in Canadian history. People still disagree about its lasting impact, especially in Quebec. Much of the debate is between those who see it as having negative economic and political effects for Quebec and French Canadians, and those who see it as positive and essential for Quebec's survival in North America. A lot of the historical discussion about the Conquest is linked to the rise of Quebec nationalism and new ways of thinking that developed during the Quiet Revolution.

The Quebec school of history, which started at Université Laval in Quebec City, believes that the Conquest was ultimately important for Quebec's survival and growth. This school includes French-speaking historians like Fernand Ouellet and Jean Hamelin. They see the positive side of the Conquest as allowing the French language, religion, and traditional customs to be preserved under British rule in a mostly English North America. They argue that the Conquest introduced French Canadians to constitutional government and parliamentary democracy. They also believe that the Quebec Act guaranteed the survival of French customs on an otherwise English-Protestant continent. Scholars like Donald Fyson have pointed to the Quebec legal system as a particular success. It kept French civil law while also introducing modern liberal ideas.

The Montreal school, which started at the Université de Montréal and includes historians like Michel Brunet, Maurice Séguin, and Guy Frégault, argues that the Conquest is responsible for Quebec's economic and political slowdown. These historians tried to explain why French Canadians were economically less successful. They argued that the Conquest "destroyed a complete society and removed its commercial leaders. The leadership of the conquered people fell to the Church. And, because British merchants took over commercial activity, national survival focused on agriculture."

A major figure of the Montreal school was the nationalist priest and historian Lionel Groulx. Groulx promoted the idea that the Conquest began a long history of underdevelopment and discrimination. Groulx argued that only the determination of the Canadiens against British rule helped French Canadians survive in a hostile North America.

Before Quebec nationalism grew, many important people saw the Conquest as positive. One provincial politician even claimed, "the last shot fired to defend the British Empire in North America would be fired by a French-Canadian." Debates among French Canadians have increased since the 1960s, as the Conquest is seen as a key moment in the history of Quebec's nationalism. Even the "pro-Conquest" Laval school is part of the larger trend of new Quebec scholarship during the Quiet Revolution. Historian Jocelyn Létourneau suggested in the 21st century that "1759 does not belong primarily to a past that we might wish to study and understand, but, rather, to a present and a future that we might wish to shape and control."

See also

In Spanish: Conquista de 1760 para niños

In Spanish: Conquista de 1760 para niños

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |