Seigneurial system of New France facts for kids

The seigneurial system (French: Régime seigneurial) was a way of dividing and owning land in New France, which is now part of Canada. It was a bit like the old feudal system used in Europe.

Under this system, the French king technically owned all the land in North America. But he didn't manage it directly. Instead, he gave large pieces of land to people called seigneurs (landlords). These seigneuries were like mini-estates. The seigneurs then rented out smaller parts of their land to farmers, who were called habitants.

The seigneurial system started in New France in 1628. Cardinal Richelieu, a powerful figure in France, gave a huge amount of land to a group called the Company of One Hundred Associates. In return, the Company had to bring settlers to New France. To do this, the Company divided the land into smaller seigneuries and gave them to seigneurs.

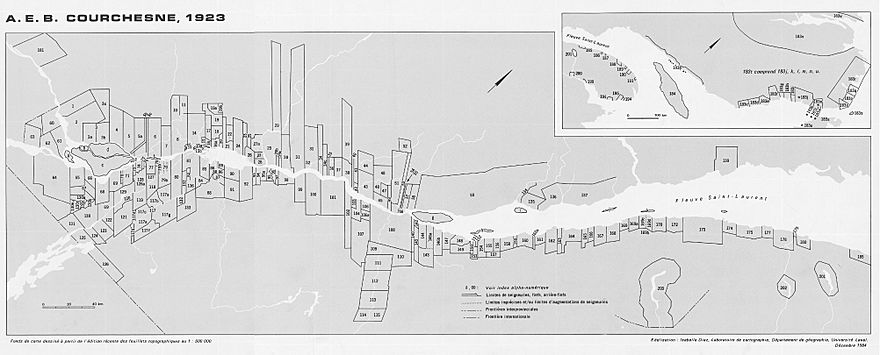

The land was usually laid out in long, narrow strips along the St. Lawrence River and other waterways. This shape made it easy for everyone to access the river for travel and trade. It also meant people lived fairly close to their neighbors.

Even with this system, not many people moved to New France. This meant there weren't enough workers, which affected how land was given out and how seigneurs and habitants interacted.

King Louis XIV made a rule that land could be taken back if it wasn't cleared and used within a certain time. This stopped seigneurs from just selling their land. Instead, they had to rent it out to farmers.

When a habitant got a piece of land, they agreed to pay yearly fees and follow some rules. The most important was rent, which could be paid in money, crops, or even work. Once the rent was set, it couldn't be changed. Habitants were mostly free to farm their land as they wished, with only a few duties to their seigneur.

Seigneurs also had duties. They had to build a gristmill (a mill for grinding grain) for their tenants. In return, habitants had to use that mill and give the seigneur a small portion of their flour. Seigneurs could also ask for a few days of free labor from the habitants and had rights over fishing, timber, and shared pastures.

Even though seigneurs' demands grew over time, they couldn't get rich just from the rents and fees. And habitants were not poor. They were free people. Both seigneurs and habitants were like owners of the land, sharing different parts of the ownership.

Contents

How Land Was Divided

The largest land divisions in New France were called estates. Within these, there were smaller divisions, often called villeinages. Thousands of these smaller farming plots were created. Most of these plots were similar in size, usually between 40 and 200 arpents (an old French unit of area), with many being 120 arpents or less. Plots smaller than 40 arpents were not considered very valuable by the farmers.

To make surveying easy, these plots were almost always rectangular. They were arranged in rows, with the first row bordering the river. The typical shape was a rectangle where the length was 10 times the width, though some were much longer. This layout made it easy to get to the river for transport and trade. It also allowed families to live close to each other, creating small communities.

As long as farmers paid their fees and improved their land, their right to the land could not be taken away. They had to clear and develop their land, or it could be taken back. A rule in 1682 said that a farmer could not hold more than two of these plots.

Different Ways to Hold Land

Seigneurs rented most of their land to tenants, known as censitaires or habitants. These farmers cleared the land, built homes, and farmed. A smaller part of the seigneurie was kept by the seigneur for their own use, called a demesne. This part was important when settlements were new, but less so later on.

The land system in New France was a bit different from France. Not all seigneurs were nobles. Many were military officers, and some land was owned by the Catholic Church. However, it was still a feudal system because wealth moved from the farmers to the landlords. This wasn't because land was scarce (there was plenty of land), but because the king set up the system this way.

| Type | What it Meant |

|---|---|

| Noble Allod en franc aleu noble |

This was a type of full ownership. If an individual held this land, it gave them the status of a noble. They didn't have to pay anything except show loyalty to the King. Only two such grants were made in New France, both to the Jesuit Order (a religious group). |

| Allod en franc aleu roturier |

Similar to the noble allod, but it didn't make you a noble. This land was free from all fees and feudal rights. |

| Frankalmoin en franche aumône |

Land given to religious, educational, or charity groups. Besides showing loyalty, they had to perform specific services. |

| Fief, Free Socage en fief (also called en seigneurie) |

This was the main way seigneuries were created. It came with certain rules:

|

| Sub-fief en arrière-fief |

This happened when a seigneur divided their seigneurie into smaller units. The new tenant owed duties to the seigneur, not directly to the King. |

| Villeinage, Villein Socage en censive or en roture |

This was the type of land held by the farmers (censitaires or habitants). They paid certain fees to the seigneur:

|

Farmers could divide their land among their children when they had families. This meant that if a parent died, half the estate went to the surviving parent, and the other half was divided among all the children (boys and girls). This sometimes led to women, especially widows, being in charge of large amounts of property. However, many widows remarried quickly, and the strict division of land was often ignored to make the new marriage easier.

To make sure each heir still had access to the river or road, the land was divided lengthwise, making the plots narrower and narrower. By 1744, this caused problems with farming. So, the King made a new rule: the smallest plot a farmer could have was one and a half arpents wide by 30-40 arpents deep. Also, the size of the seigneurie usually got bigger the further it was from a town, while the number of people living there got smaller.

This type of inheritance often led to land being broken into tiny pieces. But in New France, farming was often just enough to survive, so breaking up the land too much was impossible. It was common for one child to buy out the others' shares, keeping the land mostly together. Also, if land wasn't passed directly to children, the 1/12th entry fine had to be paid to the seigneur.

How it Affected the Economy

Some historians believe the seigneurial system slowed down economic growth in New France. For example, Morris Altman argued that it moved money from the farmers to the seigneurs. Since seigneurs' main income wasn't usually from their estates, they often used the money from fees to buy luxury goods, mostly imported from France. Altman thought that if the farmers had kept this money, they would have either invested it in their farms or bought local goods, which would have helped New France's economy grow. Other historians, like Allan Greer, also agree that this transfer of wealth limited the growth of farms and local businesses.

After British Rule

After the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759, the British took over Quebec during the Seven Years' War. The seigneurial system became a problem for British settlers because England had already ended feudal land ownership in 1660. However, the Quebec Act of 1774 kept French civil law, which meant the seigneurial system stayed in place.

The system remained largely unchanged for almost 100 years. This land was prime land. Many English and Scottish people even bought seigneuries. Over time, land continued to be divided among children and their descendants, leading to even narrower plots.

When Quebec was divided into Lower Canada (now Quebec) and Upper Canada (now Ontario) in 1791, the border was drawn along the western edge of the seigneuries near the St. Lawrence and Ottawa rivers. This explains why a small part of Quebec (Vaudreuil-Soulanges) extends into what would otherwise be Ontario. Only two seigneuries were ever set up in Upper Canada, near L'Original and Kingston. In Upper Canada, the land ownership in these seigneuries was changed to full ownership (freehold) under the Constitutional Act 1791.

Ending the System

The British Parliament tried to end the seigneurial system in 1825, allowing seigneurs and tenants to agree to change the land ownership. But few changes happened because there were no real reasons for them to do so. The Province of Canada also tried to help with a law in 1845.

The seigneurial system was officially ended by the Feudal Abolition Act 1854, which became law on December 18, 1854. This law did several things:

- It changed all feudal land ownership to full ownership.

- It ended all feudal fees and duties, replacing them with a fixed yearly payment (called a rente constituée).

- It set up a special Seigniorial Court to decide the rights of seigneurs and tenants.

- It allowed these yearly payments to be bought out (redeemed) in some cases.

After the details for each seigneurie were published in 1859, another law, The Seigniorial Amendment Act of 1859, was passed. This law allowed all feudal duties and rents (except for cens et rentes) to be bought out using money from a special fund.

Payments Continued into the 20th Century

Some parts of this land system, like the yearly payments, continued into the 20th century. People still collected these payments on the traditional date of St. Martin's Day (November 11).

The final steps to truly end these payments happened under the government of Louis-Alexandre Taschereau. Télesphore-Damien Bouchard, a politician, pushed for this. He said that many farmers still hadn't bought out their payments even after 70 years. He noted they often had to make a yearly trip to pay these fees to strangers who had bought the rights from old families.

In 1928, the Seigniories Act was changed to gather all information about these fees and their value by municipality. In 1935, the Legislature of Quebec passed the Seigniorial Rent Abolition Act. This law aimed to help free all lands from these yearly payments. It did this by:

- Creating a group called the Syndicat national du rachat des rentes seigneuriales (SNRRS), or National Syndicate for the Redemption of Rentcharges.

- Allowing this Syndicate to borrow money (with the province's guarantee) to buy out all the yearly payments.

- Creating land registers in each municipality showing the lands, owners, rents, and capital amounts.

- Allowing these payments to be bought out once the land registers were approved. The money borrowed by the Syndicate would then be paid back through a special tax on owners, which could be paid all at once or over up to 41 years.

Final Steps (1936–1970)

The plan was for seigneurs to receive their payments by November 11, 1936. However, the work of the SNRRS stopped for a few years (1936-1940) under a different government. It started again in 1940, and the last feudal payments were made in November 1940.

It was found that the yearly payments still owed were only about 25% of the original amount from 1854. Some hadn't been paid since the 1800s. To fix this, the SNRRS announced on September 15, 1940, that any money due by November 11 of that year should be paid directly to the seigneur. Any money owed after that date would be paid to the municipality.

The amounts paid to different municipalities were not equal because they didn't match the old seigneurie boundaries. Many municipalities allowed a single payment instead of a small yearly tax over 41 years. The final payment to the SNRRS from the municipalities was made on November 11, 1970, eleven years earlier than planned, thanks to good management.

What We See Today

You can still see signs of the seigneurial system today in maps and satellite pictures of Quebec. The unique "long lot" land system still shapes farm fields and clearings. It's also reflected in the old county boundaries along the St. Lawrence River. This type of land use can also be seen in Louisiana, which was also a French colony, and in parts of Manitoba and Saskatchewan where French-Canadians settled. It's even visible in the streets of Detroit, Michigan. Early streets were named after the owners of these long farms, like Livernois Street.

Sometimes, old parts of the system still pop up. In 2005, a court canceled old mortgage claims related to feudal duties on a property that was once part of Beauport Manor. Four years later, a wind farm was planned there. In 2014, a court ruled that private ownership of a lake bed and fishing rights were not given by a 1674 deed that created the Manor of La Petite-Nation.

The records of the SNRRS, which managed the end of the system, are kept in the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec. These documents are a valuable source of historical information.

A similar land system was the patroon system used by the Dutch West India Company in New Netherland. This system also gave feudal powers to "patroons" who paid for settlers. The British did not abolish this system when they took over the Dutch lands.

See Also

- Fee (feudal tenure)

- French nobility

- List of Seigneuries of New France

- List of seignories of Quebec

- Ribbon farm

- Seignory

- History of agriculture in Canada

- New France

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |