Corvée facts for kids

Corvée (pronounced "kor-VAY") is a type of unpaid work that people had to do for a certain number of days each year. Think of it as a special kind of tax, but instead of money, you paid with your time and effort!

Sometimes, a government or state would demand this work for big projects like building roads or canals. This was called statute labour. It was useful because it didn't require people to own land, crops, or cash to contribute.

For a long time before the Industrial Revolution, farmers who rented land often had to do corvée work for their landlords. This was very common in medieval and early modern Europe, where powerful landowners or kings expected their people to work for them.

Corvée wasn't just in Europe. It also happened in ancient and modern Egypt, ancient Sumer, ancient Rome, China, Japan, and the Incan civilization. Even in places like Haiti and Portugal's African colonies, this type of forced labour existed. In Canada and the United States, some forms of statute labour continued until the early 1900s.

Contents

- What Does "Corvée" Mean?

- A Look at Corvée Through History

- Corvée Today

- Images for kids

- See Also

What Does "Corvée" Mean?

The word corvée comes from ancient Rome and made its way to English through French. In the later Roman Empire, citizens sometimes did "public works" (like building roads and bridges) instead of paying taxes. Landlords could also ask their tenants and freed slaves for a certain number of workdays.

In medieval Europe, the regular tasks that serfs (farmers tied to the land) had to do for their lords each year were called opera riga. This often included plowing and harvesting. If the lord needed extra help, he could ask for opera corrogata, which meant "to requisition" or "to demand." Over time, this term changed into corvée, and it came to mean both the regular and extra work. Today, the word can even mean any annoying chore you have to do!

A Look at Corvée Through History

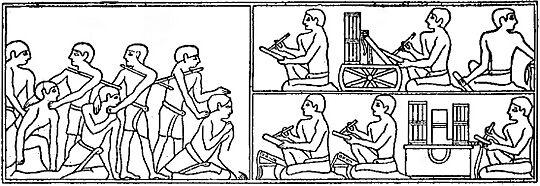

Corvée in Ancient Egypt

From the time of the Egyptian Old Kingdom (around 2613 BC), corvée was used for huge government projects. When the Nile River flooded, making farming difficult, people were put to work building amazing structures like pyramids, temples, canals, and roads.

One ancient letter from 1350 BC, called the Amarna letter EA 365, talks about providing corvée workers. This shows how common the practice was.

Later, in 196 BC, Ptolemy V mentioned in the Rosetta Stone that sailors were not allowed to be forced into labour. This suggests that forcing people into work was a normal thing back then.

Even in the 1800s, many Egyptian Public Works, including parts of the Suez Canal, were built using corvée. The British tried to end it after 1882, but it took time. By the 1890s, as Egypt became more modern, corvée had mostly disappeared.

Corvée in Europe

In medieval Europe, agricultural corvée wasn't always completely unpaid. Workers often received small payments, like food and drink, while they worked. Sometimes, corvée even included being forced to join the military or provide wagons for military transport.

Farmers really disliked corvée because their lords often demanded work at the same time they needed to tend to their own crops, like during planting or harvest. By the 1500s, corvée for farm work started to decline and was replaced more by paid labour. However, it still continued in many parts of Europe until the French Revolution and even after.

Austria and Germany

Corvée, especially a type called socage, was a key part of the feudal system in the Habsburg monarchy and many German states. Farmers and peasants had to do hard agricultural work for their nobles, sometimes for six months of the year! As money became more common, this duty slowly changed into paying taxes.

After the Thirty Years' War, the demands for corvée became too much. It officially began to decline when Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor ended serfdom in 1781. But it wasn't fully abolished until the revolutions of 1848, which also brought legal equality between nobles and common people.

In Bohemia (now part of the Czech Republic), corvée was called robota. In Russian and other Slavic languages, robota just means "work." But in Czech, it specifically meant unpaid, unfree work, like corvée or serf labour. This Czech word was later used by writer Karel Čapek in his 1920 play R.U.R., where he introduced the word robot for machines that do unpaid work.

France

In France, corvée lasted until August 4, 1789, right after the start of the French Revolution. It was abolished along with many other feudal privileges. At that time, it was mainly used for improving roads. People hated it, and it was a big reason for the widespread unhappiness that led to the revolution.

Corvée briefly returned to France in later years under different names, where men had to give three days of labour or pay money to be able to vote. It also continued in British North America under the seigneurial system of New France.

Romanian Principalities

In Romania, corvée was called clacă. It was a system where peasants had to work for their landowners (called boyars) for free. Even though the law said it was 14 days of work, it often turned into 42 days because the "average daily product" was set so high that it was impossible to finish in one day! This system was supposed to end serfdom, but it didn't really help.

A land reform in 1864 finally abolished corvée and made peasants free landowners. However, they had to pay for the land and contribute to a fund for 15 years. These debts often forced many peasants back into a life that was almost like serfdom.

Russian Empire

In the Russian Tsardom and Russian Empire, there were several types of permanent corvée called tyaglyye povinnosti, which included duties like providing carriages or lodging.

The term corvée is also used to describe barshchina, which was the forced work that Russian serfs did for their landlords on their land. While there was no official rule, an order from Paul I of Russia in 1797 suggested that three days of barshchina a week was normal and enough for the landowner.

In some regions, a large percentage of serfs (70% to 77%) performed barshchina, while others paid taxes in money or goods.

Corvée in Haiti

After Haiti became independent, the Kingdom of Haiti under Henri Christophe made its citizens do corvée work. This was used to build huge forts to protect against French invasion. Plantation owners could pay the government to have these labourers work for them instead. This helped Haiti's economy stay strong.

Later, when the U.S. Armed Forces were in Haiti from 1915 to 1934, they also used a corvée system to improve the country's roads and other buildings.

Imperial China

Ancient China also had a system of forced labour, similar to corvée. The first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, and later dynasties used it for massive public works like the Great Wall, the Grand Canal, and national roads. However, these demands were often too harsh, and punishments for not working were severe. This made Qin Shi Huang unpopular. Corvée labour was mostly ended after the Ming dynasty.

Inca Empire and Modern Peru

The Inca Empire had a system called Mit'a, where people contributed labour as a public service to the empire. At its peak, some farmers might have been called to work for up to 300 days a year! After the Spanish conquest of Peru, the Spanish took over this system to force native people to work on farms and in silver mines.

Interestingly, the Inca system of public works made a comeback in the 1960s in Peru, helping to improve the country's infrastructure.

Even today, you can find remnants of this system in modern Peru. For example, in some Quechua communities in the Andes, adults are required to do four days of unpaid work per month on community projects. This is called Mink'a.

Corvée in India

Corvée-style labour, called viṣṭi in Sanskrit, existed in ancient India and continued until the early 1900s. Ancient texts mention forced labourers helping armies. Some rules said that skilled workers should work for the king one day a month or every two weeks. For poorer citizens, forced labour was a way to pay taxes if they couldn't pay with money. Sometimes, skilled workers had to pay taxes AND work for the state.

During the Maurya Empire, forced labour became a regular way for the state to earn income. Records show rulers giving away lands and villages, sometimes with the right to demand forced labour from the people living there.

Corvée in Japan

A corvée-like system called soyōchō existed in old Japan. In the 1930s, it was common to bring forced labourers from China and Korea to work in coal mines. This continued until the end of World War II.

Corvée in Madagascar

When France took over Madagascar in the late 1800s, Governor-General Joseph Gallieni introduced a system that combined corvée with a poll tax (a tax paid by every adult). This was done to collect money, get labour after slavery was abolished, and encourage people to move away from just growing enough food for themselves. People were paid small amounts for their forced labour.

This system was an attempt to solve economic problems under colonialism. A writer in 1938 described it as a way to make the "lazy people work" and develop the economy. For example, every male Hova (a group in Madagascar) aged 16 to 60 had to either pay 25 francs a year or work 50 days for nine hours a day, for which they were paid 20 centimes (a very small amount). Soldiers, government workers, and those who knew French were exempt. Unfortunately, some people used fake contracts to avoid work and taxes. The goal was to make the colony financially independent, which the Governor-General achieved in a few years.

Corvée in the Philippines

In the Spanish Philippines, there was a system called polo y servicios. This meant that men aged 16 to 60 had to do 40 days of forced manual labour each year. They built community structures like churches. People could pay a daily fine called falla to avoid this work. In 1884, the required work was reduced to 15 days. This system was similar to forced labour systems in other Spanish colonies in America.

Corvée in Portugal's African Colonies

In Portuguese Africa (like Mozambique), a law from 1899 said that all able-bodied men had to work for six months every year. It said they could choose how to do this, but if they didn't, the authorities would force them.

Africans who only grew food for themselves were considered unemployed. This forced labour was sometimes paid, but sometimes it wasn't, as a punishment. The government benefited by using this labour for farming and building, by taxing those who worked for private employers, and by selling corvée labour to South Africa. This system, called chibalo, was not fully abolished in Mozambique until 1962.

Corvée in North America

Corvée was used in several states and provinces in North America, especially for maintaining roads. This continued to some extent in the United States and Canada. It became less popular after the American Revolution as money became more common.

After the American Civil War, some Southern states, which didn't have much money, allowed people to pay taxes with labour for public works, or pay a fee to avoid it. But this system didn't work well because the quality of work was poor. In 1894, the Supreme Court of Virginia ruled that corvée went against the state constitution. Alabama was one of the last states to abolish it in 1913.

Corvée Today

Even today, some forms of community labour or forced work still exist:

- The government of Myanmar has been known to use corvée.

- In Bhutan, the driglam namzha tradition asks citizens to do work, like building dzongs (fortresses), instead of paying some taxes.

- In Rwanda, the old tradition of umuganda, or community labour, continues. Citizens are usually required to do community work one Saturday a month.

- Vietnam used to have a "labour duty" where women (18-35) and men (18-45) had to work 10 days a year on public projects. However, this was officially abolished in 2006.

- The Pitcairn Islands, a British territory with about 50 people and no income or sales tax, has a system where all able-bodied people must perform public jobs, like road maintenance, when asked.

Since the late 1800s, most countries have limited forced labour to things like conscription (military or civilian service) or prison labour.

Images for kids

See Also

- Community service

- Penal labor in the United States

- Alternative civilian service

- Civil conscription

- Compulsory Border Guard Service

- Compulsory Fire Service

- Hand and hitch-up services

- Impressment

- Indenture

- Indigénat (corvée in French colonial Africa)

- Mit'a

- Nuribta (corvée letter to pharaoh)

- Serjeanty

- Socage

- Subbotnik

- Tax farming

- National Service

- Workfare

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |