Tsardom of Russia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Tsardom of Russia

Русское царство

Russkoye tsarstvo |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1547–1721 | |||||||||||||||

|

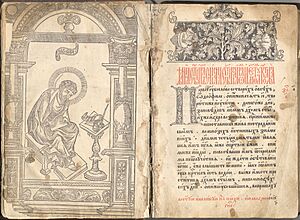

Left: The banner of the "Most Gracious Savior" was one of the variants used by Ivan IV before the adoption of state symbolism.

Right: Flag of Tsar of Moscow (c. 1693) |

|||||||||||||||

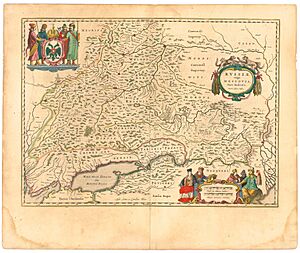

Territory of Russia in

1500, 1600 and 1700 |

|||||||||||||||

| Capital | Moscow (1547–1712) Saint Petersburg (1712–21) |

||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Russian | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Russian Orthodox | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Tsar | |||||||||||||||

|

• 1547–1584

|

Ivan IV (first) | ||||||||||||||

|

• 1682–1721

|

Peter I (last) | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Zemsky Sobor | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

|

• Coronation of Ivan IV

|

16 January 1547 | ||||||||||||||

| 1558–1583 | |||||||||||||||

| 1598–1613 | |||||||||||||||

| 1654–1667 | |||||||||||||||

| 1700–1721 | |||||||||||||||

| 10 September 1721 | |||||||||||||||

| 22 October 1721 | |||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

|

• 1500

|

6,000,000 | ||||||||||||||

|

• 1600

|

12,000,000 | ||||||||||||||

|

• 1646

|

14 million | ||||||||||||||

|

• 1719

|

15.7 million | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Russian ruble | ||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Belarus Finland Russia Ukraine |

||||||||||||||

The Tsardom of Russia was a powerful Russian state that existed from 1547 to 1721. It began when Ivan IV took the title of Tsar in 1547. It ended when Peter I created the Russian Empire in 1721.

During this time, Russia grew very quickly. From 1551 to 1700, it expanded by about 35,000 square kilometers each year. This period included big changes, like the end of the Rurik Dynasty and the start of the House of Romanov. Russia also fought many wars with countries like Poland, Sweden, and the Ottoman Empire.

A major event was the Russian conquest of Siberia, which greatly expanded Russia's territory. The Tsardom's history ended with the rule of Peter the Great. He became ruler in 1689 and made many changes. Peter transformed Russia into a strong European power. After winning the Great Northern War in 1721, he declared Russia an empire.

Contents

- How Russia Got Its Name

- The Tsar and Byzantine Heritage

- Ivan IV's Early Rule

- Ivan IV's Foreign Policies

- The Oprichnina

- The Time of Troubles

- The Romanov Dynasty

- The Legal Code of 1649

- Gaining the Wild Fields

- The Raskol (Schism)

- Conquering Siberia

- Peter the Great and the Russian Empire

- State Flags

- See also

How Russia Got Its Name

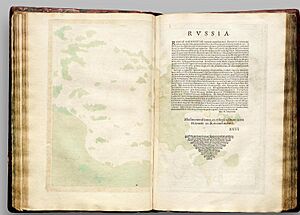

The old name for the Grand Duchy of Moscow was "Rus'". But in the 15th century, a new name, "Russia," started to appear. By the 1480s, Russian writers were using "Rosia."

In 1547, Ivan IV became "Tsar and Grand Duke of all Rus'." This officially changed the Grand Duchy of Moscow into the Tsardom of Russia. Sometimes it was called "the Great Russian Tsardom." However, many people in Europe, especially in Catholic countries, still called it "Moscovia" or "Muscovy."

The names "Russia" and "Moscovia" were both used in the 16th and 17th centuries. Some maps and books used one name, some used the other. Even in England, it was known as both Russia and Muscovy. Famous English visitors like Giles Fletcher and Samuel Collins used "Russia" in their writings.

In Russia itself, the word "Russia" replaced the old name "Rus'" in official papers. But "Rus'" and "Russian land" were still used. Sometimes, people called it "Great Russia" or "Great-Russian Tsardom."

Some historians believe "Moscovia" was used by habit. It also helped tell the difference between the Muscovite part of Rus' and the Lithuanian part. Poland also used "Moscovia" to compete with Moscow for western regions. But in Northern Europe, the country was usually known as "Russia."

The Tsar and Byzantine Heritage

By the 16th century, the Russian ruler became a very powerful leader called a Tsar. This title came from the Roman Imperial name "Caesar". By using it, the ruler of Moscow showed he was as important as the Byzantine emperor or the Mongol khan.

After Ivan III married Sophia Palaiologina, a niece of the last Byzantine Emperor, in 1472, the Moscow court adopted many Byzantine customs. These included rituals, titles, and symbols like the double-headed eagle. This eagle is still part of the coat of arms of Russia today.

The term "autokrator" first meant an independent ruler. But under Ivan IV, it came to mean a ruler with unlimited power. In 1547, Ivan IV was crowned Tsar. This meant the Russian Orthodox Church recognized him as an Emperor. A monk named Philotheus of Pskov even said in 1510 that Moscow was the "Third Rome." He believed it was the last true center of Orthodox Christianity after Constantinople fell in 1453. This idea became very important to how Russians saw themselves.

Ivan IV's Early Rule

The Tsar's power grew strongest during the rule of Ivan IV. He was known as "Grozny." In English, this is often translated as "Terrible." But "grozny" in Russian means "inspiring fear or terror; powerful; formidable." It doesn't mean "bad" or "evil." It means he was brave, magnificent, and kept enemies in fear.

Ivan IV became the Grand Prince of Moscow in 1533 when he was only three years old. Different noble families, called boyars, fought for control until Ivan took the throne in 1547. His coronation as Tsar was like the ceremonies of Byzantine emperors.

With help from some boyars, Ivan started his rule with important changes. In the 1550s, he created new laws, improved the army, and reorganized local government. These changes were meant to make the state stronger during constant wars.

Ivan IV's Foreign Policies

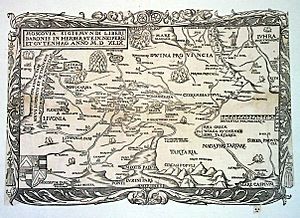

Western Europe didn't know much about Muscovy until 1549. That's when Baron Sigismund von Herberstein published his book, Notes on Muscovite Affairs. Later, in the 1630s, Adam Olearius visited Russia. His detailed writings were quickly translated and spread across Europe.

English and Dutch merchants also shared information about Russia. One merchant, Richard Chancellor, sailed to the White Sea in 1553. He then traveled overland to Moscow. When he returned to England, the Muscovy Company was formed. Ivan IV even exchanged letters with Elizabeth I.

Even with problems at home, Russia kept fighting wars and expanding. It grew from 2.8 million to 5.4 million square kilometers between 1533 and 1584. Ivan conquered the Khanate of Kazan in 1552 and later the Astrakhan Khanate. These victories made Russia a country with many different peoples and religions. The Tsar now controlled the entire Volga River and could reach Central Asia.

Expanding towards the Baltic Sea in the northwest was much harder. In 1558, Ivan attacked Livonia. This led to a 25-year war against Poland, Sweden, and Denmark. Ivan's army was pushed back, and Russia failed to get a port on the Baltic Sea.

While Russia was busy in Livonia, Devlet I Giray of Crimea attacked the Moscow region many times. He had up to 120,000 horsemen. The Battle of Molodi finally stopped these attacks. But for decades, the southern border was raided by the Nogai Horde and the Crimean Khanate. They took local people as slaves. Tens of thousands of soldiers had to protect the border, which was a heavy burden for the state.

The Oprichnina

In the late 1550s, Ivan became angry with his advisers and the boyars. Historians aren't sure why. In 1565, he split Russia into two parts. One was his private land, called the oprichnina. The other was the public land, called the zemshchina.

For his private land, Ivan chose some of the richest parts of Russia. In these areas, Ivan's agents attacked boyars, merchants, and even common people. They executed some and took their land and belongings. This started a ten-year period of terror in Russia. It ended with the terrible Massacre of Novgorod in 1570.

Because of the oprichnina, Ivan destroyed the power of the leading boyar families. These were the very people who had helped build Russia and were best at running it. Trade decreased, and peasants, facing high taxes and violence, started to leave Russia. Efforts to keep peasants on their land led Russia closer to legal serfdom. In 1572, Ivan finally stopped the oprichnina.

Some historians believe Ivan started the oprichnina to get resources for wars and stop people who opposed him. Whatever the reason, Ivan's actions had a terrible effect on Russia. They led to a time of social struggle and civil war called the Time of Troubles (1598-1613).

The Time of Troubles

Ivan IV's son, Feodor, became Tsar after him. Feodor was not interested in ruling and may have had mental health issues. The real power went to Feodor's brother-in-law, the boyar Boris Godunov. Godunov is known for ending George's Day in Autumn, which was the only time serfs could move between landowners. An important event during Feodor's rule was the creation of the Patriarchate of Moscow in 1589. This made the Russian Orthodox Church fully independent.

In 1598, Feodor died without children, ending the Rurik Dynasty. A national assembly, the Zemsky Sobor, chose Boris Godunov as Tsar. But some boyar groups refused to accept him. Then, bad harvests caused a terrible Russian famine of 1601–1603. During this unrest, a man appeared claiming to be Demetrius, Ivan IV's son who had died in 1591. This pretender, known as False Dmitriy I, gained support and marched to Moscow. Godunov died in 1605, and False Dmitriy I entered Moscow and became Tsar.

After this, Russia entered a period of great chaos called the Time of Troubles. Even though Tsars had persecuted boyars and peasants were unhappy, people didn't really try to limit the Tsar's power. Instead, unhappy Russians supported different people who claimed to be the rightful Tsar. Boyars fought among themselves, common people revolted, and foreign armies even took over the Moscow Kremlin. This made many people believe that a strong Tsar was needed to bring back order and unity.

The Time of Troubles included a civil war. The fight for the throne was made worse by rival boyar groups, other countries like Poland and Sweden getting involved, and angry people led by Ivan Bolotnikov. False Dmitriy I and his Polish soldiers were overthrown. A boyar named Vasily Shuysky became Tsar in 1606. To keep his throne, Shuysky allied with the Swedes, starting a war with Sweden. Another pretender, False Dmitry II, appeared near Moscow.

In 1609, Poland officially got involved in Russian affairs. They captured Shuysky and took over the Kremlin. In 1610, some Russian boyars signed a peace treaty. They recognized Ladislaus IV of Poland as Tsar. In 1611, False Dmitry III appeared in Swedish-controlled areas but was quickly caught and executed.

The Polish presence made Russians feel more patriotic. A volunteer army, funded by the Stroganov family and supported by the Orthodox Church, formed in Nizhny Novgorod. Led by Prince Dmitry Pozharsky and Kuzma Minin, they drove the Poles out of the Kremlin. In 1613, a zemsky Sobor chose the boyar Mikhail Romanov as Tsar. This began the 300-year rule of the House of Romanov.

The Romanov Dynasty

The first job for the new Romanov dynasty was to bring back order. Luckily, Russia's main enemies, Poland and Sweden, were fighting each other. This allowed Russia to make peace with Sweden in 1617. The Polish–Muscovite War (1605–1618) ended with the Truce of Deulino in 1618. This agreement temporarily gave Poland and Lithuania back some lands, like Smolensk, that they had lost earlier.

The early Romanov rulers were not very strong. Under Mikhail, his father, Filaret, handled state matters. Filaret became Patriarch of Moscow in 1619. Later, Mikhail's son Aleksey (ruled 1645-1676) relied on a boyar named Boris Morozov to run his government. Morozov used his power to take advantage of people. In 1648, Aleksey fired him after the Salt Riot in Moscow.

After failing to take back Smolensk from Poland in 1632, Russia made peace with Poland in 1634. Polish king Władysław IV Vasa gave up all claims to the Russian throne as part of the peace treaty.

The Legal Code of 1649

The autocracy survived the Time of Troubles because the government's central offices were strong. Government workers kept doing their jobs, no matter who was ruling. In the 17th century, the government grew a lot. The number of government departments increased from 22 in 1613 to 80 by the mid-century.

The Sobornoye Ulozheniye, a full legal code from 1649, shows how much the state controlled Russian society. By this time, the old boyars had joined with a new group of state servants to form a new nobility. The state required both old and new nobles to serve, mostly in the military. This was because of constant wars on the borders and attacks from nomads. In return, the nobles received land and peasants.

In the century before, the state had slowly limited peasants' rights to move between landowners. The 1649 code officially tied peasants to their home. This meant serfdom was fully allowed. Runaway peasants became state fugitives. Landlords had complete power over their peasants.

However, peasants on state-owned land were not considered serfs. They were organized into communes and were responsible for taxes. But like serfs, they were tied to the land they farmed. City workers and craftsmen also paid taxes and could not change where they lived. Everyone had to serve in the military or pay special taxes. By tying most of Russian society to specific places, the 1649 legal code limited movement and made people serve the state's interests.

This code, with its higher taxes and rules, led to more unhappiness that had been building since the Time of Troubles. In the 1650s and 1660s, many more peasants ran away. A popular hiding place was the Don River region, home of the Don Cossacks.

A big uprising happened in the Volga region in 1670 and 1671. Stenka Razin, a Cossack from the Don River, led a revolt. He gathered wealthy Cossacks and runaway serfs looking for free land. This unexpected uprising spread up the Volga River valley and even threatened Moscow. The Tsar's troops finally defeated the rebels after they had taken over major cities along the Volga. Razin was publicly executed.

Gaining the Wild Fields

The Tsardom of Russia kept growing in the 17th century. In the southwest, it claimed the Wild Fields (now Eastern Ukraine and parts of South-Western Russia). These lands had been under Polish-Lithuanian rule. The people there wanted help from Russia to leave Polish rule.

The Zaporozhian Cossacks were warriors organized in military groups. They lived in the border areas near Poland and the Crimean Tatar lands. Even though some served in the Polish army, the Zaporozhian Cossacks were very independent. They often rebelled against the Poles.

In 1648, peasants in what is now Eastern Ukraine joined the Cossacks in a rebellion. This was the Khmelnytsky Uprising. They were fighting against the social and religious oppression they faced under Polish rule. At first, the Cossacks allied with the Crimean Tatars, who helped them fight the Poles. But when the Poles convinced the Tatars to switch sides, the Cossacks needed new military help.

In 1648, Bohdan Khmelnytsky, the leader of the Zaporozhian Host, offered to ally with the Russian tsar, Aleksey I. Aleksey accepted this offer, which was agreed to in the Treaty of Pereyaslav in 1654. This led to a long war between Poland and Russia.

The Truce of Andrusovo ended the war in 1667. This truce split the Cossack territory along the Dnieper River. The western part went back to Poland, and the eastern part became self-governing under the Tsar. However, this self-government did not last long. The Cossack territory was eventually fully taken into the Russian Empire after the Battle of Poltava in the 18th century.

The Raskol (Schism)

Russia's expansion southwest, especially taking over the Wild Fields, had unexpected results. Most people in Little Russia (modern-day Eastern Ukraine) were Orthodox. But their close contact with Roman Catholic Poland brought them Western ideas. Through the Academy in Kiev, Russia gained links to Polish and Central European influences.

The Russian Orthodox Church found that its isolation from Constantinople had caused differences in its liturgical books and practices. The Russian Orthodox patriarch, Nikon, wanted to make the Russian texts match the Greek texts and practices of the time. But many Russians opposed Nikon. They saw these changes as wrong foreign influences.

When the Orthodox Church forced Nikon's reforms, a split happened in 1667. Those who did not accept the reforms were called the Old Believers. They were officially declared heretics and were persecuted by the church and the state. Their main leader, Avvakum, was burned at the stake. The split became permanent, and many merchants and peasants joined the Old Believers.

The Tsar's court also felt the influence of Little Russia and the West. Kiev was a major source of new ideas through the famous academy founded there in 1631. Other direct links to the West opened as international trade grew and more foreigners came to Russia. The Tsar's court was interested in the West's more advanced technology, especially for military uses. By the end of the 17th century, Western influences had changed Russian culture, especially among the elite. This prepared the way for even bigger changes.

Conquering Siberia

Russia's expansion eastward faced little resistance. In 1581, the Stroganov family, who were interested in the fur trade, hired a Cossack leader named Yermak Timofeyevich. He led an expedition into western Siberia. Yermak defeated the Khanate of Sibir and claimed the lands west of the Ob River and Irtysh Rivers for Russia.

From places like Mangazeya, merchants, traders, and explorers pushed eastward. They went from the Ob River to the Yenisei River, then to the Lena River and the Pacific Ocean coast. In 1648, the Cossack Semyon Dezhnev opened the passage between America and Asia. By the mid-17th century, Russians had reached the Amur River and the edges of the Chinese Empire.

After some conflict with the Qing dynasty, Russia made peace with China in 1689. By the Treaty of Nerchinsk, Russia gave up its claims to the Amur Valley. But it gained access to the region east of Lake Baikal and a trade route to Beijing. Peace with China strengthened Russia's reach to the Pacific Ocean.

Peter the Great and the Russian Empire

Peter the Great (1672–1725) became the full ruler in 1696. He brought the Tsardom of Russia, which had little contact with Europe, into the main flow of European culture and politics. After stopping many rebellions with much bloodshed, Peter went on a secret trip to Western Europe. He was very impressed by what he saw and realized how behind Russia was.

Peter started to require nobles to wear Western clothes and shave their beards. The boyars strongly protested this. Arranged marriages among nobles were banned, and the Orthodox Church was brought under state control. Military schools were created to build a modern European-style army and officer group. This replaced the old, disorganized armies used by Muscovite rulers.

These changes did not make Peter popular. They caused big political divisions in the country. His cruel actions, like the torture and death of his own son for planning a rebellion, and the great suffering caused by his projects, like building Saint Petersburg, made many religious Russians believe he was the Antichrist.

The Great Northern War against Sweden took up much of Peter's time for years. However, the Swedes were finally defeated, and peace was made in 1721. Russia took the Baltic coast from Sweden and parts of Finland. This area became the site of the new Russian capital, Saint Petersburg. Russia's victory in the Great Northern War was a turning point in European politics. It showed that Sweden and Poland were no longer major powers, and Russia had become a permanent, strong force in Europe. Expansion into Siberia also continued. A war with Persia brought new land in the Caucasus, though Russia gave up those gains after Peter's death in 1725.

State Flags

The Tsardom did not have just one flag. Instead, there were several different flags used:

- Standards used by the Tsar:

- Standard of the Tsar of Russia (1693–1700): This flag was white, blue, and red with a golden double-headed eagle in the center. It was replaced in 1700.

- Imperial Standard of the Tsar of Russia: This flag had a black double-headed eagle carrying a red coat of arms on a golden rectangle. It was adopted in 1700.

- Civil flag: The early Romanov Tsars used the two-headed eagle Imperial Flag as a Civil Flag. It was used until 1858.

- Civil ensign of Russia: This was the white, blue, and red tricolor flag. It was adopted on January 20, 1705, by Peter I.

- Naval ensign of the Imperial Russian Navy: This flag was white with a blue saltire (X-shape). It was adopted in 1712. Before that, the naval flag was the white-blue-red tricolor.

- Naval jack of the Imperial Russian Navy: This flag was red with a blue saltire. It was adopted in 1700.

See also

In Spanish: Zarato ruso para niños

In Spanish: Zarato ruso para niños

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |