Polish–Muscovite War (1605–1618) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Polish–Muscovite War (1605–1618) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Time of Troubles and the Russo-Polish Wars | |||||||||

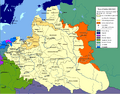

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and western Tsardom of Russia during the Polish–Russian War. The map displays Poland (white), Lithuania (dark red), Russia (dark green), and Polish territorial gains or areas temporarily controlled by Poland (pink). Positions of military regiments and important battles are marked with crossed swords. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

The Polish–Muscovite War of 1605–1618 was a big conflict between the Tsardom of Russia and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Zaporozhian Cossacks also joined the Polish side. This war happened during a difficult time in Russia called the Time of Troubles.

Russia faced many problems after Tsar Feodor I died in 1598. There was no clear ruler, and a huge famine hit the country. Poland saw this as a chance to gain power and land. Polish nobles supported people who pretended to be the dead Russian prince, Dmitry. These pretenders were called "False Dmitrys."

In 1605, Polish nobles and their armies invaded Russia. They supported False Dmitry I, but he was killed in 1606. Another pretender, False Dmitry II, appeared, leading to more fighting. In 1609, Polish King Sigismund III officially declared war. His goal was to take land and weaken Sweden, Russia's ally.

Polish forces won important battles, like the Battle of Klushino. In 1610, they even entered Moscow. Sigismund's son, Prince Władysław, was chosen as the new Tsar by some Russian nobles. However, Sigismund wanted Władysław to make Russians convert to Catholicism. This made many Russians turn against the Poles.

In 1611, Russian heroes Kuzma Minin and Prince Dmitry Pozharsky formed a new army. They led a popular uprising against the Polish occupation. Polish forces were forced out of Moscow in 1612. In 1613, Michael Romanov was elected Tsar, starting the Romanov dynasty. This ended the Time of Troubles. The war finally ended in 1618 with the Truce of Deulino. Poland gained some land, but Russia kept its independence.

This war was the first major sign of the long-lasting rivalry between Poland and Russia. It shaped Russian society for centuries. It also inspired many famous works of art, like plays, operas, and films.

Contents

- Understanding the War's Different Names

- Why the War Started: Russia's Troubles

- First Polish Invasion: The Rise of False Dmitry I (1605–1606)

- Second Polish Invasion: False Dmitry II (1607–1609)

- The Polish–Muscovite War (1609–1618)

- What Happened After the War

- The War's Impact Today

- See also

- Images for kids

Understanding the War's Different Names

This conflict has several names. It is often called the Russo–Polish War. In Poland, it is known as the Dimitriads. This refers to the two main parts: the First Dymitriad (1605–1606) and the Second Dymitriad (1607–1609). The later part (1609–1618) is called the Polish–Muscovite War. In Russia, these events are part of the "Time of Troubles". Russians often call it the Polish Invasion or Polish Intervention.

Why the War Started: Russia's Troubles

In the late 1500s and early 1600s, Russia was in a very bad state. It faced political and economic problems. After Tsar Ivan IV (known as "the Terrible") died in 1584, and his son Dimitri died in 1591, many groups fought for the throne.

In 1598, Boris Godunov became Tsar. This ended the long rule of the Rurik dynasty. Many people questioned if Godunov was the rightful ruler. Some even thought he was involved in Dimitri's death. Godunov tried to control his opponents, but he couldn't stop them completely.

To make things worse, the early 1600s were very cold. This caused a terrible famine from 1601 to 1603. People were starving, and the country was in chaos.

In 1600, Polish leaders visited Moscow. They suggested an alliance between Poland and Russia. They even proposed that if one ruler died without heirs, the other would rule both countries. But Tsar Godunov said no. He only agreed to extend an old peace treaty.

Polish King Sigismund and his nobles knew they couldn't easily invade Russia. The Polish army was small, and the country's money was low. Also, many people in Poland did not want a war. However, as Russia got weaker, Polish nobles saw a chance to gain from the chaos. Many Russian nobles, called boyars, were unhappy with the civil war. They asked Poland for help. Some wanted to become Tsar themselves. Others hoped for a union with Poland, similar to Poland's "Golden Freedom" for nobles.

The idea of a union between Poland and Russia was discussed. It would mean a shared foreign policy and army. Nobles could live and buy land in either country. There would be free trade and a single currency. More religious tolerance was also proposed, especially for non-Orthodox churches in Russia. Russian noble children could even study in Polish schools.

But this plan never gained much support. Many Russian boyars feared that joining Catholic Poland would harm Russia's Orthodox traditions. They opposed anything that threatened Russian culture.

First Polish Invasion: The Rise of False Dmitry I (1605–1606)

King Sigismund III had his own problems, like wars with Sweden. But in 1603, a man claiming to be Prince Dmitry appeared in Poland. He was called False Dmitry I. Powerful Polish nobles, like Michał Wiśniowiecki, supported him. They gave him money for a campaign against Tsar Godunov. These nobles hoped to gain wealth and control over Russia through False Dmitry.

Catholic leaders also saw Dmitry as a way to spread their faith in the East. They gave him money and education. Sigismund did not officially support Dmitry with the full Polish army. But he liked the idea of spreading Catholicism. He gave Dmitry enough money for a few hundred soldiers. Dmitry promised Poland "half of Smolensk territory" if he became Tsar.

When Tsar Boris Godunov heard about Dmitry, he said the man was just a runaway monk named Grigory Otrepyev. But Godunov's support in Russia was fading. Many Russian boyars pretended to believe Dmitry. This gave them a reason not to pay taxes to Godunov.

Dmitry gathered followers and a small army. About 3,500 Polish soldiers from private armies joined him. Around 2,000 southern Cossacks also joined. In June 1604, Dmitry rode into Russia. His army won a battle at Novhorod-Siverskyi. They captured several towns. But they lost badly at the Battle of Dobrynichi. Dmitry's army almost fell apart.

His luck changed when Tsar Boris Godunov suddenly died on 13 April 1605. This removed the biggest obstacle for Dmitry. On 20 June, Dmitry triumphantly entered Moscow. On 21 July, he was crowned Tsar. He chose a new church leader, Patriarch Ignatius, who was the first to recognize him as Tsar.

Dmitry strengthened his alliance with Poland by marrying Marina Mniszech. She was a Polish noblewoman. Marina refused to convert to the Russian Orthodox faith. This angered many Russians. She was crowned Tsarina in Moscow in May.

Dmitry's rule was not very strong. Many boyars felt they could gain more power for themselves. They were also worried about Polish influence. Dmitry's court had many foreigners from Poland. The "Golden Freedoms" that Dmitry supported threatened the most powerful boyars.

So, the boyars, led by Prince Vasily Shuyski, plotted against Dmitry. They accused him of bringing Polish customs and selling Russia to Catholic leaders. They gained popular support. This was because Dmitry was openly supported by a few hundred Polish soldiers. These soldiers were in Moscow and often caused trouble, angering the local people.

On 17 May 1606, about two weeks after his wedding, plotters attacked the Kremlin. Dmitry tried to escape through a window but broke his leg. One of the plotters shot him dead. His body was later burned, and his ashes were reportedly shot from a cannon towards Poland. Dmitry had been Tsar for only ten months. Vasili Shuyski became the new Tsar. About 500 of Dmitry's Polish supporters were killed or forced to leave Russia.

Second Polish Invasion: False Dmitry II (1607–1609)

Tsar Vasili Shuyski was not popular and his rule was weak. He was seen as anti-Polish. He had led the plot against False Dmitry I. He had also killed over 500 Polish soldiers in Moscow. The civil war continued in Russia.

In 1607, False Dmitry II appeared. Again, some Polish nobles supported him. Marina Mniszech even claimed he was her first husband, False Dmitry I. This brought him support from Polish nobles who had backed the first Dmitry. Nobles like Jan Piotr Sapieha gave him money and about 7,500 soldiers.

His army, especially the Lisowczycy mercenaries, caused a lot of damage. People in Russia even said there were "three plagues: typhus, Tatars and Poles." In 1608, the Lisowczycy defeated Tsar Vasili Shuyski's army at the Battle of Zaraysk. They captured towns like Mikhailov and Kolomna.

The Lisowczycy then moved towards Moscow. But they were defeated at the Battle of Medvezhiy Brod. They lost most of their stolen goods. Polish commander Jan Piotr Sapieha failed to capture the Troitse-Sergiyeva Lavra monastery. But the Lisowczycy had success (and stole goods) in other cities like Kostroma and Soligalich.

Dmitry II quickly captured more towns. More Poles joined him. In spring 1608, he marched on Moscow. He defeated Tsar Vasily Shuyski's army at Bolkhov. Dmitry promised to take land from the boyars. This made many common people join his side. He set up a camp near Moscow. His forces grew to over 100,000 men. He even made Feodor Romanov a Patriarch. Dmitry gained control of many cities. But his luck was about to change. Poland decided to get more involved in the Russian civil wars.

The Polish–Muscovite War (1609–1618)

Polish Victories and the Siege of Smolensk (1609–1610)

In 1609, Tsar Vasili made a military alliance with Charles IX of Sweden. Polish King Sigismund III saw this as a chance to regain the Swedish throne. He also wanted to expand Poland's territory and influence. He hoped to make Orthodox Russia Catholic. The Pope strongly supported this idea.

Sigismund also wanted to give a purpose to his restless former opponents. He promised them wealth and fame in Russia. A Polish nobleman, Paweł Palczowski, wrote a book in 1609. It compared Russia to the rich empires of the New World. He said it was full of gold and easy to conquer. This book was meant to encourage Polish nobles to support the war.

Some Russian boyars offered the throne to Sigismund's son, Prince Władysław. Sigismund had not wanted to commit many Polish forces to Russia before. But these factors made him change his mind.

Many Polish soldiers were fighting for False Dmitry II. But Sigismund III and his army did not support Dmitry. Sigismund wanted the Russian throne for himself. Sigismund's entry into Russia caused most of Dmitry II's Polish supporters to leave him. This helped lead to Dmitry II's defeat. Dmitry II fled and tried to attack Moscow again. He still had support from the Don Cossacks.

A Polish army led by Hetman Stanisław Żółkiewski crossed the border. On 29 September 1609, they began the siege of Smolensk. Smolensk was an important city. Russia had taken it from Lithuania in 1514. The city was defended by fewer than 1,000 Russian soldiers. Żółkiewski had 12,000 troops.

Smolensk had a very strong fortress built in 1602. The Poles found it impossible to break through. They settled into a long siege. They fired cannons, tried to dig tunnels, and built earth walls. The siege lasted 20 months. Finally, with help from a Russian defector, the Poles captured the fortress.

Not all Polish attacks were successful. An early attack led by Hetman Jan Karol Chodkiewicz failed. His unpaid army rebelled and forced him to retreat. The war changed when Prince Władysław arrived with more soldiers. Meanwhile, the Lisowczycy captured and looted Pskov in 1610. They also fought the Swedes in Russia.

There were different ideas in the Polish camp. Some wanted Dmitry or even Shuyski to be elected king instead of Sigismund. Żółkiewski, who was against invading Russia, disagreed with Sigismund. Żółkiewski wanted a peaceful union with Russia. He offered Russian boyars rights and religious freedom. He imagined a Polish–Lithuanian–Muscovite Commonwealth. He believed diplomacy was better than force.

But Sigismund III did not want to compromise. He was a strong supporter of the Catholic Church. He believed he could take Moscow by force. Then he would establish his own rule and Roman Catholicism.

Poles Enter Moscow (1610)

On 31 January 1610, some boyars who opposed Tsar Shuyski asked Władysław to become the Tsar. Sigismund agreed on 24 February, but only if Moscow was peaceful.

Hetman Żółkiewski followed the king's orders. He left a small force at Smolensk and marched on Moscow. He had Cossack reinforcements. As he had feared, many Poles' supporters left them. This happened as Polish forces moved east and Sigismund's refusal to compromise became clear.

Russian forces tried to help Smolensk. They fortified a fort at Tsaryovo-Zaymishche. This was to block the Poles' advance. But the Russians were not ready for a long siege. They had little food and water. Tsar Shuyski's brother, Dmitry Shuyski, marched to help them. He had Swedish forces with him.

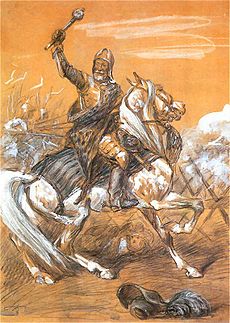

Żółkiewski learned about Shuyski's army. He divided his troops to meet them. He left at night so the Russians at Tsaryovo wouldn't notice. The combined Russian and Swedish armies were defeated on 4 July 1610. This was at the battle of Klushino (Kłuszyn). About 7,000 Polish elite cavalry, the winged hussars, defeated a much larger Russian army of 35,000–40,000 soldiers. This huge defeat shocked everyone.

After the news of Klushino, support for Tsar Shuyski disappeared. Żółkiewski convinced the Russian units at Tsaryovo to surrender. They swore loyalty to Władysław. He added them to his army and moved towards Moscow. In August 1610, many Russian boyars accepted Władysław as the next Tsar. They agreed if he converted to Orthodoxy. The Russian Duma voted to remove Tsar Shuyski from the throne. Shuyski and his family were captured. He was later sent to Warsaw as a war trophy.

Soon after Shuyski was removed, Żółkiewski and False Dmitry II arrived in Moscow. It was a confusing time. Different groups fought for control. The Russian people were unsure if the Poles were invaders or allies. After some small fights, the pro-Polish group gained control. The Poles were allowed into Moscow on 8 October. The boyars opened Moscow's gates. They asked Żółkiewski to protect them from chaos. Polish troops then guarded the Moscow Kremlin.

On 27 July, a treaty was signed. It promised Russian boyars the same rights as Polish nobles. In return, they would recognize Władysław as the new Tsar. But Żółkiewski did not know that Sigismund had other plans.

Żółkiewski and False Dmitry II, who were once allies, started to disagree. False Dmitry II lost much of his influence. Żółkiewski tried to remove Dmitry from the capital. Żółkiewski wanted a Polish Tsar, especially the 15-year-old Prince Władysław. The boyars had offered the throne to Władysław twice. They hoped the liberal Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth would end the harsh rule of their Tsars.

Żółkiewski worked to get Władysław elected. Most boyars agreed to support Władysław as Tsar. But only if he converted to Orthodoxy. And if Poland returned the fortresses they had captured.

However, Sigismund was against his son converting. He was a very strong supporter of the Catholic Church. He believed he could conquer Moscow and make it Catholic. This disagreement caused the planned union to fall apart. The boyars were offended by Sigismund. They became slow to support Władysław. They were divided between electing Vasily Galitzine, Michael Romanov, or False Dmitry II.

Żółkiewski acted quickly. He made promises without the king's approval. The boyars elected Władysław as the new Tsar. Żółkiewski sent Fyodor Romanov, Michael's father and the patriarch of Moscow, out of Russia. This was to secure Polish support. After Władysław's election, False Dmitry II fled to Kaluga. He was killed on 20 December by one of his own men. Marina Mniszech was pregnant with a new "heir" to the Russian throne. She remained involved in Russian politics until her death in 1614.

Władysław faced more opposition from his own father. When Żółkiewski met Sigismund at Smolensk in November, Sigismund had changed his mind. He decided he wanted the Russian throne for himself. Most Russians opposed this. Sigismund did not hide his plan to make Russia Catholic and Polish.

Żółkiewski was in a difficult spot. He had promised the boyars Prince Władysław. He knew they would not accept Sigismund III. Żółkiewski, disappointed with Sigismund, returned to Poland. Sigismund eventually agreed to let his son take the throne. But he would rule as a regent until Władysław was old enough. He demanded that boyars swear loyalty to him as well. The boyars resisted this. Support for the Poles quickly disappeared.

Władysław never gained real power. The war soon started again. Sigismund and Władysław left Moscow for safety. The small Polish army in the Kremlin became isolated. More and more boyars turned against the Poles. Polish forces outside Moscow fought against the growing Russian forces. These were led by Prokopy Lyapunov.

Meanwhile, the siege of Smolensk continued. Even though Władysław was named Tsar, Smolensk refused to open its gates. Żółkiewski fortified Moscow and returned to King Sigismund III at Smolensk. The siege continued for a long time. The Poles finally broke through the outer wall. But the inner wall remained strong. The siege continued.

The War Continues: Russian Uprising (1611)

In 1611, an uprising in Moscow against the Polish soldiers began. This showed that Russians no longer tolerated Polish involvement. Moscow citizens had helped in the 1606 coup, killing Polish soldiers. Now, ruled by Poles, they rebelled again. The citizens took over the weapons store. Polish troops fought back, and a large fire destroyed part of Moscow.

From July onwards, the Polish forces faced serious problems. The uprising turned into a siege of the Polish-held Kremlin. The Poles had imprisoned the leader of the Orthodox Church, Patriarch Hermogenes. When Russians attacked Moscow, the Poles ordered him to sign a statement to stop the attack. Hermogenes refused and was starved to death. The Polish soldiers in the Kremlin were now under siege.

In late 1611, Prince Dmitry Pozharsky was asked to lead the fight against the Poles. Merchants from Nizhny Novgorod organized this. A respected meat-trader, Kuzma Minin, managed the money donated by merchants. They formed the Second Volunteer Army.

In January 1612, part of the Polish army rebelled. They had not been paid. They left Russia and returned to Poland. This strengthened the Russian forces in Moscow. The 9,000-strong Polish army, led by hetman Jan Karol Chodkiewicz, tried to break the siege. They fought Russian forces on 1 September. The Poles used cavalry attacks and a mobile fortress. After some early Polish successes, Russian Cossack reinforcements forced Chodkiewicz's army to retreat from Moscow.

Russian forces under Prince Pozharsky eventually starved the Polish soldiers in the Kremlin. They were forced to surrender on 1 November (or 6/7 November) after a 19-month siege. Some reports say the Polish soldiers ate grass and even each other. On 7 November, the Polish soldiers left Moscow. Although they were promised safe passage, Russian forces killed half of them. The Russian army had recaptured Moscow.

On 2 June 1611, Smolensk finally fell to the Poles. The Russian defenders had endured 20 months of siege and two harsh winters. A traitor helped the Polish army find a weak spot in the fortress. On 13 June 1611, an explosion created a large hole in the walls. The fortress fell that day. The remaining 3,000 Russian defenders went into a cathedral. They blew themselves up with gunpowder to avoid being captured. Losing Smolensk was a blow. But it freed up Russian troops to fight in Moscow. The Russian commander at Smolensk, Mikhail Borisovich Shein, was seen as a hero. He was captured and remained a prisoner for nine years.

A Break in Fighting (1612–1617)

After Smolensk fell, the border between Russia and Poland was mostly quiet for a few years. No official peace treaty was signed. Sigismund was criticized by the Polish parliament for failing to keep Moscow. He received little money for the army. This led to a rebellion by the Polish regular army. This rebellion, called the konfederacja rohaczewska, was very large and violent. It looted Polish territories from 1612 until it was defeated in 1614.

Meanwhile, Russia's Time of Troubles was not over. Russia was too weak to take advantage of Poland's problems. On 21 February 1613, a Russian assembly chose Michael Romanov as the new Tsar. He was 16 years old. Michael's father, Patriarch Filaret, was a popular boyar. The Romanovs were a powerful family. Michael's great-aunt was the wife of Ivan the Terrible.

The new Tsar Michael had many opponents. Marina Mniszech tried to make her child Tsar until her death in 1614. Other boyar groups still fought for power. Sweden also intervened, trying to put Duke Carl Philip on the throne. But Philip got even less support than Władysław. The Swedes were soon forced to leave Russia.

While both countries had internal problems, smaller groups thrived. Polish Lisowczycy mercenaries helped defend Smolensk in 1612. They guarded the Polish border for three years. In 1615, Aleksander Józef Lisowski gathered outlaws and invaded Russia. He besieged Bryansk and defeated a Russian army. Lisowski then defeated a much larger Russian force. He burned towns and returned to Poland with much loot. Lisowski died in 1616, but his forces remained a threat. In 1616, they captured Kursk and defeated Russian forces at Bolkhov.

The Final Push (1617–1618)

Finally, the Polish parliament voted to raise money for more military actions. Sigismund and Władysław made a final attempt to gain the Russian throne. A new campaign started on 6 April 1617. Władysław was the official commander, but Hetman Chodkiewicz was in charge. In October, the towns of Dorogobuzh and Vyazma quickly surrendered. They recognized Władysław as the Tsar.

However, Polish forces met strong resistance near Mozhaisk. Chodkiewicz's plan for a quick advance to Moscow failed. Władysław did not have enough soldiers to march on Moscow again. Russian support for the Poles was almost gone by then. In 1618, Petro Sahaidachny and his Zaporozhian Cossacks agreed to join the campaign. His army invaded from the South. They captured and sacked many towns. They then headed for Moscow.

The Russian army retreated to Moscow. On 2 October, Chodkiewicz and Sahaidachny began a siege of the Russian capital. But their armies were not ready for a long siege. A night attack on October 10–11 failed. The siege was lifted shortly after. Negotiations began, and a peace treaty was signed in December 1618.

What Happened After the War

In the end, Sigismund did not become Tsar. Władysław also did not secure the throne. But Poland did expand its territory. During Sigismund's reign, Poland-Lithuania was the largest and most populated country in Europe. On 11 December 1618, the Truce of Deulino was signed. This treaty ended the war. It gave Poland control over some conquered lands. These included Chernigov, Severia, and the city of Smolensk. It also set a 15-year truce. Władysław still claimed the Russian throne, even though Sigismund had given up his claim. Poland gained some land, but it was a very costly victory in terms of money and lives.

In 1632, the Truce of Deulino ended. Fighting immediately started again in a conflict called the Smolensk War. This time, Russia started the war. They tried to take advantage of Poland's weakness after Sigismund III's death. But they failed to regain Smolensk. Mikhail Shein surrendered to Władysław IV in 1634. The Russians accepted the Treaty of Polyanovka in May 1634. Russia had to pay money to Poland. But Władysław gave up his claim to the Russian throne. He recognized Michael as the rightful Tsar of Russia. He also returned the Russian royal symbols.

The War's Impact Today

The story of the False Dmitrys was used by future rulers in Poland and Russia. In Poland, the war is remembered as a great time for the country. It was when Poles captured Moscow. This was something even much larger armies in later centuries could not do.

In Russia, the new Romanov dynasty used this history. They wanted to show the war as a heroic defense of Russia. They said it was against a "barbaric invasion" by Poland. This version of history was shown in famous works. These included Alexander Pushkin's "Boris Godunov" and Modest Mussorgsky's opera. The film Minin and Pozharsky also showed this view. The Monument to Minin and Pozharsky was built in Moscow's Red Square in 1818.

After the Soviet Union, Russia created a new holiday. It is called National Unity Day. It is celebrated on 4 November. This day remembers the uprising that forced foreign forces out of Moscow in 1612. It also marks the end of the Time of Troubles. The holiday celebrates how all parts of Russian society united to save their country. President Vladimir Putin brought back this holiday in 2004. It replaced the old October Revolution holiday. This helped to focus on Russian nationalism.

See also

In Spanish: Guerra polaco-rusa (1605-1618) para niños

In Spanish: Guerra polaco-rusa (1605-1618) para niños

- Prince Władysław's March on Moscow

- Time of Troubles (1598–1615)

- Smolensk War (1632–1634)

- 1612, a Russian historical drama film about the expulsion of Polish troops from Moscow

Images for kids

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |