Yermak Timofeyevich facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Yermak Timofeyevich

|

|

|---|---|

17th century portrait of Yermak, the first Russian leader of the exploration and conquest of Siberia

|

|

| Born | between 1532 and 1542 |

| Died | August 5 or 6, 1585 (aged 43–53) Sibiryak, Qashliq, Khanate of Sibir, Russia

|

| Occupation | soldier, explorer, porter, sailor, river pirate |

| Known for | The cossack who led the Russian exploration and conquest of Siberia, in the reign of Tsar Ivan the Terrible |

Yermak Timofeyevich (born between 1532 and 1542 – August 5 or 6, 1585) was a brave Cossack leader, known as an ataman. Today, he is a famous hero in Russian stories and legends. During the time of Tsar Ivan the Terrible, Yermak began the Russian takeover of Siberia.

Russians wanted to expand east into Siberia to find valuable furs. The Tatar Khanate of Kazan was a key entry point into Siberia. In 1552, Ivan the Terrible's modern army defeated this khanate. After taking Kazan, the tsar looked to the rich Stroganov merchant family to lead the expansion eastward. In the late 1570s, the Stroganovs hired Cossack fighters to explore Asia for the tsar. These Cossacks chose Yermak as their leader. In 1582, Yermak set out with 840 soldiers to attack the Khanate of Sibir.

On October 26, 1582, Yermak and his soldiers defeated Kuchum Khan's Tatar empire at Qashliq. This battle is often called the "conquest of Siberia." Yermak stayed in Siberia and kept fighting the Tatars until 1584. Sadly, a raid by Kuchum Khan's forces surprised and killed Yermak and his group.

Many details about Yermak's life, like his appearance or exact dates, are still debated by historians. This is because the old texts about him are not always reliable. However, his life and victories greatly influenced Siberia. They sparked Russia's interest in the region and made the Tsardom of Russia a powerful empire east of the Urals.

Contents

Discovering Yermak's Story

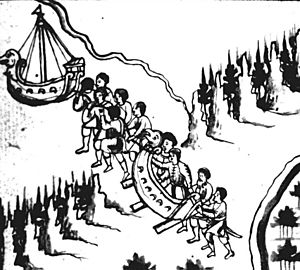

We have less information about Yermak than about most other famous explorers. Much of what we know comes from old stories and folklore. There are no descriptions of Yermak from his own time, so all his portraits are just guesses. One old Siberian book, the Remezov Chronicle, was written over 100 years after Yermak died. It describes him as “flat-faced, with a black beard and curly hair, of medium height, thick-set and broad-shouldered.” But even this detailed description might not be true, as the writer never met Yermak.

The details of Yermak's early life and how he ended up in Siberia are also unclear. Russian writer Valentin Rasputin noted how little we know about Yermak, even though he did so much for Russia.

Historians find it hard to piece together Yermak's life because the two main sources about him might not be fully accurate. These sources are the Stroganov Chronicle and the Sinodik. The Stroganov Chronicle was ordered by the Stroganov family. So, it might make their role in the conquest of Siberia seem bigger than it was. The Sinodik was written 40 years after Yermak's death by Cyprian, the archbishop of Tobolsk. This text was based on stories passed down and memories. But it was likely influenced by the archbishop's wish to make Yermak a saint. Because details could have been forgotten or changed over time, the Sinodik might not be completely correct. Even though Cyprian didn't succeed in making Yermak a saint, he tried to make the warrior famous forever.

These documents, along with others about Yermak, have contradictions. This makes it hard to know the full truth about his life. Even though these sources might have mistakes, they are all historians have. So, they are generally accepted as reflecting the truth.

Yermak's Early Life and Work

Family Background

The Cossack warrior Yermak Timofeyevich was born near the Chusovaya River. This area was on the eastern edge of the Russian lands. The only information about Yermak's childhood comes from a source called the Cherepanov Chronicle. This book was put together by a coachman in Tobolsk in 1760, long after Yermak died. A historian named A.A. Dmitrieyev believed it was likely a copy of an older document from the 1600s.

According to this chronicle, Yermak's grandfather, Afonasiy Grigor'yevich Alenin, came from Suzdal, a town northeast of Moscow. To escape poverty, he moved south to Vladimir. There, he became a coachman in the Murom forests. A local official, a voyevoda, arrested him for driving robbers who had hired him. Afonasiy's son, Timofey (Yermak's father), then moved to the Stroganov lands on the Chusovaya River to find work.

His Jobs and Adventures

Yermak worked for the Stroganov family's river fleet. He was a porter and a sailor, moving salt along the Kama and Volga rivers. He grew tired of this work and formed a group. He left his job and moved to the Don region to become a river pirate. Among his fellow Cossack bandits, he earned the nickname Yermak.

Before his conquest of Siberia, Yermak had experience fighting. He led a Cossack group for the tsar in the Livonian War and robbed merchant ships. Legends say that for years, Yermak had been robbing and plundering on the Volga River with other Cossack leaders. One historian called Yermak's group "his gang of thugs." It was common for Cossacks to engage in piracy on the Sea of Azov or the Caspian Sea. They would also rob messengers and merchants. Even though he was a bandit, Yermak became known as a skilled and loyal Russian fighter. His experience in the Livonian War taught him war tactics, making him better than other Cossack leaders.

Why Russia Explored Siberia

In the late 1500s, before Yermak's trips, Russians tried to move east into Siberia to find furs. Under Ivan the Great, Russians entered northwest Siberia. But it was too hard to get there from that direction. So, they decided a southern route through the Tatar khanate of Kazan would be easier. But first, Kazan had to be defeated.

Ivan the Terrible's first goal when he became tsar was to take Kazan. His modern army succeeded in October 1552. Ivan then opened up the east for Russian business people, like the Stroganovs. Anika Stroganov used the former Kazan khanate as a way into Siberia. He built a private business empire in the southwest part of Siberia.

After Russia conquered Kazan, the Tatar khanate became the Russian province of Perm. Ivan the Terrible trusted the Stroganov family's business skills. He gave them the province of Perm as an investment that would help Russia. The tsar also allowed the Stroganovs to expand into lands along the Tobol and Irtysh Rivers. These lands belonged to the Muslim leader Kuchum Khan. The Stroganovs then launched expeditions eastward into non-Russian areas. They pushed into the khanate of Sibir, which was like a sister state to the former Kazan khanate. Sibir controlled the fur trade in western Siberia.

While Russia was conquering Kazan in the 1540s and 1550s, Sibir was having its own conflicts with rival groups. The khanate was unstable until Kuchum Khan, a descendant of the famous Chingis Khan, rose to power in the 1560s. Kuchum Khan made alliances with his neighbors and the Crimean Tatars. He wanted to stop the Stroganovs from expanding across the Urals. In July 1572, Kuchum launched his first attack on Stroganov settlements, killing almost 100 people. In 1573, the Tatar army grew and changed leaders. Kuchum's nephew, Mahmet-kul, took control of the Tatar army.

The Stroganovs realized their settlers would not stay in Perm if they only defended themselves. The tsar gave the Stroganov family permission to invade Asia. However, the tsar soon changed his mind. He told the Stroganovs to pull back from Siberia. He feared Russia did not have enough resources or soldiers to defeat Kuchum Khan's empire.

The Stroganovs decided to ignore the tsar's orders. In the late 1570s, Anika Stroganov's grandsons, Nikita and Maksim, hired Cossack fighters to wage war for them. They chose the Cossack chieftain Yermak Timofeyevich to lead the Cossack groups. According to the Stroganov Chronicle, on April 6, 1579, the Stroganovs heard about Yermak's "daring and bravery." They sent him a letter asking him and his comrades to come to their lands in Chusovaya. They wanted them to fight the Tatars in the tsar's name. Since Yermak was the most famous of the recruits, he became the captain (ataman) of the "conquest of Siberia."

There is some debate about whether Yermak decided to fight on his own, without being asked by the Stroganovs. This question comes from differences between the Stroganov Chronicle and another Siberian chronicle, the Yesipov Chronicle. The Stroganov Chronicle says the family was the main reason for Yermak's campaign. But the Yesipov Chronicle doesn't even mention the family. Perhaps the Stroganovs told the story in a way that would make Russians feel grateful to them, as well as to Yermak, for conquering Siberia. Historians are divided on this. Some believe the Stroganovs were behind Yermak's campaign, while others think they played no part.

Yermak's Conquest of Siberia

Yermak officially joined the Stroganovs in the spring of 1582. His mission was to take control of the land along the Tobol and Irtysh rivers. This land was already legally owned by the Stroganovs under the Tsar's charter of 1574. The Stroganovs' main goal was to open a southern route to Mangaseya to get its furs. The Khanate of Sibir blocked the path from the Urals to Mangaseya. After defeating the khanate, Yermak's final destination was supposed to be the Bering Strait, a journey of 5,000 miles.

Yermak led a small army of 840 men. This included 540 of his own followers and 300 supplied by the Stroganovs. His army was made up of "Russians, Tatars, Lithuanians, and Germans." The Lithuanians and Germans came from the Lithuanian front. Nikita and Maksim Stroganov spent 20,000 rubles to equip the army with the best weapons. This was a big advantage for the Russians, as their Tatar enemies did not have industrial weapons. According to historian W. Bruce Lincoln, the Tatars' "bows, arrows, and spears" faced Yermak's team's "matchlock muskets, sabers, pikes, and several small cannons." However, another author, Yuri Semyonov, said Yermak had no cannons and only a few men had firearms. The Cossacks had no horses, while Kuchum and his men were mounted. Kuchum's cavalry could move quickly, but the Cossacks were tied to their rafts, which carried all their supplies.

Yermak started his journey through Siberia from a fort in Perm on the Chusovaya River on September 1, 1582. Other sources say he might have started in 1579 or 1581. When traveling down rivers, the crew used tall, Russian-made boats. During their journey, they faced strong resistance from Kuchum Khan's allies. But the high sides of their boats protected them like shields. When crossing the Urals, the Cossacks had to carry their belongings on their backs because they had no horses. After two months, Yermak's army finally crossed the Urals. They followed the Tura River and reached the edge of Kuchum Khan's empire. Soon, they arrived at the capital city of Qashliq.

On October 23, 1582, Yermak's army fought the Battle of Chuvash Cape. This started three days of fighting against Kuchum's nephew, Mehmet-kul, and the Tatar army. Yermak's foot soldiers stopped the Tatar attack with heavy musket fire. This wounded Mahmet-kul and meant the Tatars didn't cause a single Russian casualty. Yermak successfully captured Qashliq, and this battle became known as the "conquest of Siberia."

While Yermak had taken Qashliq, the battle had reduced his Cossack force to 500 men. Yermak also faced a supply problem. The army found treasures like fur, silk, and gold in the Tatar city, but no food. The people had also fled, so they couldn't get help from them. However, four days after Yermak claimed Qashliq, the people returned. Yermak soon became friends with the Ostyak people. The Ostyaks formally promised their loyalty to Yermak on October 30, bringing food to the city.

Yermak used the Ostyak tributes (gifts) to feed his Cossacks through the winter. But these supplies were not enough. The Cossacks soon went into the wilderness to fish and hunt. This was not easy, because even though Yermak had defeated the Tatars, they kept bothering the Cossacks. This stopped Yermak from fully controlling the region. The Tatars struck a big blow on December 20, when a group of 20 Cossacks was found and killed. When they didn't return, Yermak left the city to investigate. He found that Mahmet-kul had recovered from their earlier battle and was responsible for the Cossacks' deaths. Yermak then fought Mahmet-kul and his forces again, defeating him once more.

Defeating Mahmet-kul gave the Cossacks a short break. But in April 1583, he returned to the region. By chance, Mahmet-kul was quickly ambushed and captured by a small group of Cossacks. A few days after his capture, Mahmet-kul sent a message to Kuchum saying he was alive and well. He also asked the Khan to stop attacking the Cossacks and those bringing tribute to Yermak. Yermak used this peaceful time to travel down the Irtysh and Ob rivers. He wanted to complete his control over the local tribal leaders. He soon met the Ostyak prince Demian, who had fortified himself in a fortress on the Irtysh with 2,000 fighters. It took Yermak and his men a long time to break through their defenses. Yermak's forces eventually won.

After this, Yermak continued down the river, capturing the important Ostyak town of Nazym. Yermak's friend, Ataman Nikita Pan, and several Cossacks died in the battle. Yermak then led his forces down the Ob River, conquering several small forts. After reaching a point where the river was very wide, Yermak stopped the expedition and returned his forces to Qashliq.

Upon returning to Qashliq, Yermak decided to tell the Stroganovs and the tsar about his victories. His reasons are unclear, but experts believe he wanted to clear his name from past wrongdoings. Yermak also desperately needed supplies. So, he sent his trusted officer Ivan Kolzo with 50 men, two letters (one for the Stroganovs and one for Ivan the Terrible), and many furs for the tsar. The exact amount sent to the tsar is debated, with descriptions ranging from 2,500 to 5,000 furs.

Kolzo's arrival at the Stroganovs' home was well-timed. Maksim Stroganov had just received a letter from Ivan denouncing Yermak and threatening him and his followers with death. Kolzo, bringing news of Kuchum's defeat, Mahmet-kul's capture, and the takeover of Tatar lands, was welcomed by a relieved Maksim. Maksim gave Kolzo a place to stay, food, and money before sending him on his way.

Kolzo reached Moscow and was allowed to meet Ivan, even though he had a price on his head. The Livonian War had just ended, and Ivan was getting reports of local tribes raiding Perm, which put him in a bad mood. But when he read Kolzo's news about his new territories, Ivan was overjoyed. He immediately pardoned the Cossacks and declared Yermak a great hero. Church bells rang throughout Moscow to celebrate Yermak. Ivan then prepared many gifts for Yermak. These included his personal fur cloak, a goblet, two suits of armor with bronze double-headed eagles, and money. Ivan also ordered a group of streltsy (soldiers) to be sent to help Yermak. Reports differ on whether 300 or 500 men were sent. The Stroganovs were also ordered to support this group with 50 more men when they arrived in Perm. Ivan gave Yermak the title "Prince of Siberia." He also commanded that Mahmet-kul be sent to Moscow.

When Kolzo returned to Qashliq, he told Yermak about the tsar's order to send Mahmet-kul to him. Yermak knew that doing this would remove Kuchum's only reason for peace. But he obeyed the tsar and arranged for Mahmet-kul's transport. As expected, Kuchum's forces began to attack more often. Yermak was in a difficult situation. A long winter had prevented them from gathering supplies, and the tsar's reinforcements had not yet arrived. The Stroganovs had sent 50 cavalrymen with the reinforcement party, as ordered by the tsar. But the horses slowed the group down across Siberia, and they didn't even cross the Urals until the spring of 1584.

In September 1583, a Tatar leader named Karacha sent a plea for help to Yermak. He asked for assistance against the Nogai Tatars. Yermak was cautious of Karacha but still wanted to help. He sent Kolzo with 40 Cossacks. However, Karacha could not be trusted. Kolzo and his men walked into a trap and were all killed. Now without Kolzo, Yermak had little more than 300 men left. Sensing Yermak's weakening power, the tribes he had controlled rebelled. Qashliq was soon surrounded by a combined army of Tatars, Voguls, and Ostyaks. They cleverly encircled the city with wagons, blocking entry and exit while protecting themselves from Russian firearms. Yermak, despite limited supplies, held out for three months.

However, the Cossacks could not last forever. On the cloudy night of June 12, 1584, Yermak decided to act. His men quietly went through the line of wagons. They surprised the attackers in their sleep, killing many. Since Karacha's forces were completely unaware, Yermak was able to get a lot of supplies from the barricade. Karacha, having failed, was punished by Kuchum, who sentenced Karacha's two sons to death. Karacha, fueled by the loss of his sons, gathered the native tribes and returned to attack Yermak the next day. But Karacha's forces were soundly defeated. The Cossacks killed 100 men while only losing two dozen of their own.

Defeated, Karacha fled south to the steppes of the Ishim, where Kuchum was waiting. Freed from being trapped, Yermak went on the attack. He conquered many towns and forts east of Qashliq, expanding the tsar's control. Having already won back the loyalty of the rebelling tribes, Yermak continued sailing up the Irtysh throughout the summer of 1584. He subdued tribes and demanded tribute. Although he tried to find Karacha, Yermak was unsuccessful. Also, while Yermak had regained the tribes' loyalty, his men were almost completely out of gunpowder. To make matters worse, his reinforcements arrived exhausted and sick with scurvy. Many of the men, including their commander, had not survived the journey. So, in addition to facing more attacks, their food shortage became even worse with more men to feed.

Yermak's Final Battle

The exact details of Yermak's death are not fully known, but many legends tell different versions of the story. As the food shortage worsened, Yermak's men faced famine. Kuchum, knowing this, set a trap. The most common story says that Kuchum purposely let information leak to Yermak. The rumor was that Bukharan merchants from Central Asia, carrying lots of food, were being stopped by Kuchum's men.

In August 1584, Yermak set out with a group of men to free the traders. He found the reports were false. Yermak ordered a return to Qashliq. Either because of a storm or because the men were tired from rowing upstream, Yermak's group stopped on a small island formed by two branches of the Irtysh. They set up camp on the night of August 4–5, 1584. Believing the river offered protection, Yermak's men fell asleep without a guard.

However, Kuchum had been following Yermak's party and was waiting. Kuchum's forces crossed the river around midnight. The loud storm and dark night hid their approach. Kuchum's Tatars attacked Yermak's men so quickly that they couldn't use their guns or weapons. A massacre followed. It is said that all but three Russians were killed, including Yermak. Legend says that after fighting through the attackers and being wounded in the arm, Yermak found their boats had been washed away in the storm. He tried to cross the river. But because of the heavy armor given to him by the Tsar, Yermak sank to the bottom and drowned. At least one survivor, not burdened by heavy armor, managed to swim across the river and return to Qashliq with news of Yermak's death.

Yermak's body floated down the river. Seven days later, a Tatar fisherman named Yanish is said to have found it. Yermak was easily recognized by the eagle on his armor. His body was used by archers for target practice. However, it is said that animals did not touch him, and his body caused fear and nightmares among the people. Respecting these signs, the Tatars buried him as a hero. His valuable armor was later divided among the Tatar chiefs.

Yermak's Lasting Impact

When the Cossacks heard about Yermak's death, they immediately lost morale. The original group of men had shrunk to 150 fighters. Command now fell to Glukhoff, the leader of the first group of reinforcements the tsar had sent. The Cossacks soon decided to leave Qashliq and retreat to Russia. Before they went far, they met a group of 100 reinforcements sent by the tsar. With this good turn of events, Yermak's group decided to return to Qashliq and strengthen their position, as the tsar wished.

However, the quick-thinking Tatars had learned of the group's flight. They had retaken the city almost immediately, preventing any peaceful return to their former stronghold. Although the Tatar position seemed strong, they were no longer led by Kuchum, who had lost his power. So, they were not as stable as before. Also, another 300 reinforcements from the tsar soon arrived to join the Russians. Led by Tchulkoff, this new force greatly boosted the fighting strength of the group.

Despite the unstable Tatar leadership and their new recruits, the Russians did not try to take Qashliq again. Instead, in 1587, they founded a new settlement where Tobolsk would later be. This was a comfortable 12 miles from Qashliq. Although the Tatars quickly began raids against their old enemy, they stopped after a short time, leaving the Russians to their new town.

Yermak's heroic efforts in the Russian East prepared the way for future Russian expansion and settlement. Soon after Yermak and his first group went to Siberia, merchants and farmers followed. They hoped to get some of the rich furs found in the land. This trend grew even more after Yermak's death. His legend spread quickly, and with it, news of a land rich in furs and open to Russian influence.

Colonization attempts soon followed. Tyumen, the first known town after Yermak's death, was founded in 1586. Settling this territory helped establish and develop farming in Siberia. Most of these farmers were actually soldiers who grew their own food out of necessity.

Yermak set a pattern for Cossack involvement in Siberian expansion. The explorations and conquests of these men were responsible for many additions to the Russian empire in the east. After the Cossacks' initial return shortly after Yermak's death, a big project to build forts began under Boris Godunov. Its successes, including protecting Russians in the region, would draw even more business people to Siberia.

In 1590, Tobolsk became much more important. It was named the main city and administrative center of the region. The fur trade also continued to grow, helped by the Cossacks. In 1593, they set up the trading center of Berezof on the Ob River. The practice of collecting furs as tribute from the natives continued to spread. In the 1600s, such furs made up 25–33 percent of the tsar's treasury income. So, just 15 years after Yermak's death, the Ob River basin truly became a region under Russian influence. Even so, the Russians did not stop there. The speed of expansion started by Yermak continued well into the 17th century. Within the first half of the century, the fort of Yeniseysk was built in 1619, the city of Yakutsk founded in 1632, and the important achievement of reaching the Sea of Okhotsk on the Pacific coast in 1639. Throughout these campaigns, Yermak's influence was clear. The pace he set for achievements in his relatively short time in Siberia started a new age of Russian pioneering.

Yermak's life and conquests greatly changed Russian policy towards Siberia and the colonization attempts that followed. Before Yermak's agreement with the Stroganovs, Russia's attitude towards Siberia was mainly about defense, not attack. The top priority was to push back the Tatar groups. As shown by Ivan's letter to the Stroganovs, the government rarely got involved unless the tribes entered Russian territory. This changed with Yermak. His victories showed that the Tatars could be put on the defensive. Russia could now become an aggressive power in the East.

Yermak also changed the tsar's involvement in Siberian affairs. By reaching out to the tsar for help, Yermak gained government support. In fact, it was reinforcements from the tsar that secured the Russian presence in the region right after Yermak's death. This new commitment is best shown by Ivan's acceptance of the title Yermak gave him: "Tsar of Sibir." Yermak's pioneering also allowed this system to exist. It depended on his success in getting tribute from conquered peoples. Like Yermak, future troops were sent with the understanding that they would need to add to their basic pay with treasures and tributes gained from conquest. Without this system, it's unlikely such an arrangement would have happened.

Future explorers also learned from Yermak's strategy in approaching Siberian lands. Unlike many other colonization attempts, these lands already had an established empire. However, Yermak wisely realized that Kuchum's territories were not united. Yermak noted that many of these peoples were just vassals (people who owed loyalty to a lord). They were very different in terms of race, language, and religion. Unlike Kuchum and his Muslim Tatars, many of these groups were pagan. Because of all these differences, many simply paid tribute to avoid trouble. It didn't matter much to whom the tribute was paid. Yermak's unique strength was recognizing this bigger picture. He then quickly and effectively established influence in the region.

Yermak's actions also changed the meaning of the word Cossack. It's not certain if Yermak's group was related to the Yaik or Ural Cossacks. But it is known that his group was previously outlawed by the Russian government. However, by sending his letter and his trusted officer Ivan Kolzo to Ivan the Terrible, Yermak changed the image of the Cossack overnight. They went from being bandits to soldiers recognized by the Tsar of Moscow. Now, Yermak's Cossacks were part of the military system and could get support from the tsar.

This new arrangement also helped relieve pressure on the Cossacks, who had often caused trouble on the Russian frontier. By sending as many of them as possible further east into unconquered lands, the growing and very profitable lands on the borders of Russian territory got a break. Yermak's call for help created a new type of Cossack. Because of their link to the government, they would receive much favor from future Russian rulers. Despite this new change, the Cossack name stayed in Siberia. Soldiers sent as reinforcements often adopted this title. However, this change was not without criticism. Some saw Yermak as a traitor to the Cossack name. Such critics believed Yermak's death was punishment for turning away from the Cossack code and becoming a tool of the tsar. Fittingly, it was his armor, the very symbol of the tsar, that pulled him down to his death.

Even years after his death, items belonging to Yermak continued to hold great power and importance. In particular, the search for his armor affected Siberian relations. Decades after Yermak's death, a Mongol leader who had helped the Russian government approached the voyevoda (governor) of Tobolsk. He asked for help in getting an item held by the Tatars, believed to be Yermak's armor. He had previously tried to trade for it with ten slave families and a thousand sheep, but the Tatars refused. The Tatars, who believed the armor had divine powers, agreed to the sale when the voyevoda got involved. Soon after, the Mongol, convinced of the armor's power, refused to serve the Russian government because he no longer feared their might.

Remembering Yermak

Many statues and monuments have been built in Yermak's honor across Russia. V. A. Beklemishev began building a monument dedicated to Yermak in 1903. It is in Cathedral Square in Novocherkassk, the capital of the Don Cossack country. On the monument, Yermak is shown holding his military banner in his left hand and the ceremonial cap of his rival Kuchum Khan in his right hand. The back of the monument reads: “To the Don Cossack Ataman Ermak Timofeyevich, the Siberia conqueror from the grateful posterity. In honor of Don Cossack Army 300th Anniversary. He passed away in Irtysh waves on August 5, 1584.” Some believe Yermak was born in the village of Kachalinskaya on the Don River. Although this region has long claimed Yermak as one of its own, there is no proof he was born there or ever visited.

There is also a statue of Yermak at Tobolsk. Another one is in the State Russian Museum in Saint Petersburg, designed by Mark Antokolsky.

Two icebreaker ships have been named after Yermak. The first, built in Newcastle, England, in 1898, was one of the first large icebreaker ships ever built. The second, which started service in 1974, was the first of an impressive new type of ship.

To remember Yermak, there is a town named after him on the upper Irtysh River. Also, a mountain in the Perm Region, made up of three cliff stacks, is called the Yermak Stone after Yermak. Legend says that Yermak and his group spent one harsh Siberian winter on the side of this cliff.

See also

In Spanish: Yermak Timoféyevich para niños

In Spanish: Yermak Timoféyevich para niños

- History of Siberia

- Exploration of Siberia

- Exploration of Asia

- Russian conquest of Siberia

- Conquest of the Khanate of Sibir