History of Siberia facts for kids

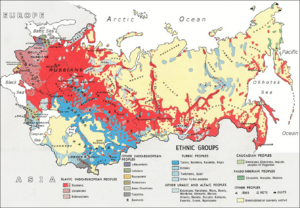

Siberia is a huge region in northern Asia. Its early history was shaped by powerful nomadic groups like the Scythians and Xiongnu. These groups lived in the steppes (grassy plains) of Siberia long before our modern calendar began. Later, other nomadic peoples, including various Turkic peoples and the Mongol Empire, also lived here. In the late Middle Ages, Tibetan Buddhism spread to areas south of Lake Baikal.

During the time of the Russian Empire, Siberia became important for farming. The government also used it as a place to send people who were exiled (forced to leave their homes), like Fyodor Dostoevsky and the Decembrists. In the 1800s, the famous Trans-Siberian Railway was built. This helped Siberia grow its industries, especially after people found huge amounts of minerals there.

Contents

Who Lived in Siberia First?

Scientists believe that people first lived in Siberia around 45,000 BCE. From here, they spread out to Europe and the Americas. Some of these early people were the ancestors of the Ainu people in Japan.

One of the oldest groups in Central Siberia were the Yeniseians. They spoke a language different from later groups. The Kets are thought to be the last remaining people from this very early migration. Many people also crossed the Bering Land Bridge from Siberia into North America over 20,000 years ago.

Many ancient remains have been found near Siberian lakes, showing that many people lived there long ago. People from the Neolithic age left behind countless burial mounds called kurgans. They also left furnaces and other tools.

Later, the Samoyeds came from the Ural Mountains. They were skilled at working with bronze, silver, and gold. They also used irrigation to help their farming in fertile areas.

Between 700 and 300 BCE, the Scythians lived in the Altai region. They were a big influence on later empires in the steppes. Trade also began early, with silk goods being traded along the Silk Road in Siberia.

Around 300 BCE, the Xiongnu empire started. This caused many people to move, especially to the northern parts of Siberia. Turkic people like the Yenisei Kirghiz were already in the Sayan region. Other Turkic tribes moved northwest and took control of the Ugric people.

These new groups also left many signs of their time in Siberia. They knew how to use iron and learned bronze casting from the people already living there. Their pottery was more artistic than before. Many of their beautiful ornaments are now in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg.

Siberia in the Middle Ages

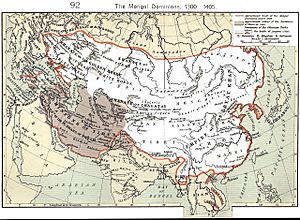

How the Mongols Conquered Siberia

The Mongols had long known the people of the Siberian forests. They called them "people of the forest." Many of these groups were similar to the Mongols. Some spoke Mongol languages, while others spoke Turkic, Samoyedic, or Yeniseian languages.

By 1206, Genghis Khan had united all the Mongol and Turkic tribes. In 1207, his son Jochi conquered the Siberian forest people. He organized them into large groups called tumens. Genghis Khan also brought Chinese craftspeople and farmers to live in Siberia. The Mongol leaders valued special falcons, furs, and horses from Siberia as tribute.

Western Siberia came under the rule of the Golden Horde. This area was ruled by the descendants of Jochi's son, Orda Khan. They even set up dog sled stations to help collect tribute in the swampy parts of western Siberia.

Later, in 1270, Kublai Khan sent a Chinese official to be a judge in the Kyrgyz and Tuvan areas. From 1275, Ögedei's grandson Kaidu took over parts of Central Siberia. But in 1293, the Yuan dynasty army took back the Kyrgyz lands. After that, the Yuan dynasty controlled large parts of Central and Eastern Siberia.

Novgorod and Muscovy's Influence

As early as the 1000s, people from Novgorod sometimes traveled into Siberia. In the 1300s, they explored the Kara Sea and the Ob River in West Siberia. When the Novgorod Republic fell, its connections to Siberia were taken over by the Grand Duchy of Moscow.

In 1483, Moscow troops moved into West Siberia, traveling along rivers like the Tavda and Irtysh. In 1499, Muscovites and Novgorodians went to West Siberia on skis and conquered some local tribes.

The Khanate of Sibir

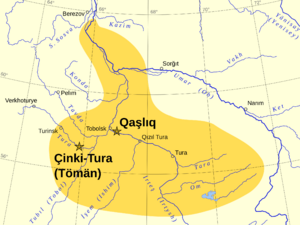

When the Golden Horde broke apart in the late 1400s, the Khanate of Sibir was formed. Its main city was Tyumen. Different ruling families fought for control of this area.

In the early 1500s, Tatar people from Turkestan took control of the tribes living east of the Ural Mountains. They brought farmers, leather workers, merchants, and Muslim religious leaders from Turkestan. Small kingdoms appeared along the Irtysh River and the Ob River. These kingdoms often clashed with the Russians who were settling in the Urals. In 1555, the Khan of Sibir agreed to pay a yearly tribute of furs to Moscow.

Yermak and the Cossacks

In the mid-1500s, the Tsardom of Russia conquered the Tatar kingdoms of Kazan and Astrakhan. This opened the way to the Ural Mountains. Rich merchants called the Stroganovs led the settlement of these new eastern lands. Tsar Ivan IV gave the Stroganovs large areas of land and tax breaks. The Stroganovs started farming, hunting, and trading with Siberian tribes.

In the 1570s, the Stroganovs hired many cossacks to protect their settlements from attacks by Khan Kuchum of the Siberian Khanate. In 1577, they suggested that the Cossack leader Yermak conquer the Khanate of Sibir. They promised to give him food and weapons.

In 1581, Yermak began his journey into Siberia with 1,636 men. The next year, 500 of his men successfully attacked Qashliq, Khan Kuchum's home. After several victories, Yermak's forces defeated Kuchum's main army in 1582. Kuchum's army retreated, leaving his lands to Yermak. Yermak then offered Siberia to Tsar Ivan IV.

However, Kuchum was still strong. In 1585, he launched a surprise attack on Yermak at night, killing most of his men. Yermak was wounded and drowned while trying to swim across a river. Yermak's Cossacks had to leave Siberia. But new groups of hunters and adventurers, supported by Moscow, kept coming into the country every year. Because Yermak had explored the main river routes, Russians were able to take back his conquests just a few years later.

Russian Exploration and Settlement

In the early 1600s, Russia had some internal problems, which slowed down their eastward movement. But soon, the exploration of Siberia started again. This was mostly led by Cossacks looking for valuable furs and ivory.

Some Russians came from the Southern Urals, while others came by the Arctic Ocean. These were Pomors from Northern Russia, who had been trading furs in Western Siberia for a long time. In 1607, the settlement of Turukhansk was founded. In 1619, Yeniseysk was built.

In 1620, a group of fur hunters led by Demid Pyanda began a very long journey. Stories say that from 1620 to 1624, Pyanda explored almost 5,000 miles (8,000 km) of unknown Siberian rivers. He explored the Lower Tunguska and then found the great Lena River. He may have been the first Russian to reach Yakutia and meet the Yakuts. He also explored the Angara River and realized it was the same as the Upper Tunguska.

In 1627, Pyotr Beketov became a leader in Yenisey, Siberia. He successfully collected taxes from the Buryats and became the first Russian to enter Buryatia. He founded the first Russian settlement there, Rybinsky ostrog (fortress). In 1631, Beketov was sent to the Lena River. In 1632, he founded Yakutsk and sent his Cossacks to explore more rivers and build new forts.

Yakutsk quickly became a main base for Russian expeditions. In 1638, Maksim Perfilyev became the first Russian to enter Transbaikalia. In 1639, a group led by Ivan Moskvitin became the first Russians to reach the Pacific Ocean and discover the Sea of Okhotsk. They learned about the nearby Amur River. In 1640, they sailed south, exploring the coast and possibly reaching the Amur River's mouth. Based on Moskvitin's stories, Kurbat Ivanov drew the first Russian map of the Far East in 1642. In 1643, Ivanov himself discovered Lake Baikal.

In 1643, Vasily Poyarkov crossed the Stanovoy Range and reached the upper Zeya River. He was the first Russian to reach the Amur River in 1644. He sailed down the Amur and found its mouth. Since his Cossacks had made enemies, Poyarkov took a different way back, sailing along the Sea of Okhotsk coast.

In 1644, Mikhail Stadukhin discovered the Kolyma River. In 1648, a merchant named Fedot Alekseyev Popov and Semyon Dezhnyov sailed from the Kolyma River to the Arctic. They rounded Cape Dezhnyov, becoming the first explorers to pass through the Bering Strait. They discovered Chukotka and the Bering Sea. Most of their men were lost, but Dezhnyov's small group reached the Anadyr River and founded Anadyrsk.

In 1649–50, Yerofey Khabarov explored the Amur River. He faced armed resistance from the local people. He built winter camps and charted the Amur River.

By the mid-1600s, Russians had explored almost all of Siberia. The conquest of Kamchatka was finished later, in the early 1700s, by Vladimir Atlasov. The Arctic coastline and Alaska were explored by the Great Northern Expedition from 1733–1743. This expedition helped cartographers create maps of most of Russia's northern coast. At the same time, scientists from the new Russian Academy of Sciences traveled through Siberia, becoming the first scientific explorers of the region.

Russian People and Siberian Natives

The main reason Cossacks came to Siberia was for valuable furs from sables, foxes, and ermines. Local people who joined the Russian Empire received protection from southern nomads. In return, they had to pay a tribute called yasak in the form of furs.

Some local peoples fought against the Russians, while others agreed to join them. However, sometimes they later refused to pay tribute or accept Russian rule. As Russians moved east, they met less developed local people, who often resisted more. The Evenks fought for their independence but were subdued around 1623. The Buryats also resisted but were quickly brought under control. The most resistance came from the Koryaks and Chukchi, who were still living at a Stone Age level.

The Manchu people resisted, forcing the Russian Cossacks to leave Albazin. By the Treaty of Nerchinsk (1689), Russia stopped its advance into the Amur River basin. Instead, Russia focused on settling Siberia and trading with China. In 1852, a Russian military group explored the Amur. By 1857, Russians had settled along the entire river. China recognized this in 1860 with the Treaty of Aigun.

Scientists Explore Siberia

Scientists began exploring Siberia from 1720 to 1742. These early explorers included Daniel Gottlieb Messerschmidt and Johann Georg Gmelin. Later, Peter Simon Pallas and his students started a detailed study of Siberia's land, animals, plants, and people. Many other scientists also visited Siberia, adding to the scientific knowledge of the region.

The Siberian branch of the Russian Geographical Society was founded in Irkutsk. It became a permanent center for exploring Siberia. The opening of the Amur River and Sakhalin also attracted more scientists who wrote about Siberia's nature and people.

Russian Settlement and Growth

In the 1600s and 1700s, Russians who moved to Siberia were hunters or people escaping from Central Russia. These included peasants looking for freedom from serfdom, convicts, and Old Believers. New Russian settlements and local peoples needed protection from nomads, so forts like Tomsk and Berdsk were built.

By the early 1700s, the threat of nomad attacks lessened. More people moved to Siberia, and normal city life began. In the 1700s, Siberia became a new administrative region called a guberniya with Irkutsk as its center. In the 1800s, it was divided into more regions.

In 1730, the first large industrial project started in Siberia. The Demidov family built a metal production plant, which led to the city of Barnaul. This city later had a library, club, and theater. A visitor in 1856–1857 called Barnaul "the most cultured place in Siberia."

Similar things happened in other cities. Public libraries, museums, colleges, and theaters were built. However, the first university in Siberia didn't open until 1880 in Tomsk.

Siberian peasants were very independent. They had to deal with the harsh climate on their own. Since there was no serfdom and plenty of land, they could farm a plot for several years, then let it rest and use other land. They had plenty of food, unlike peasants in European Russia. Their houses were often large, two-story homes, different from typical Russian houses.

Siberia in the Russian Empire

Decembrists and Other Exiles

Siberia was considered a good place for political exiles because it was far from other countries. People from Saint Petersburg would find it hard to escape in the vast Siberian countryside. Even large cities like Irkutsk and Omsk did not have the busy social life of the capital.

About eighty people involved in the Decembrist revolt were sent to work in Siberia and live there forever. Eleven of their wives followed them. In their writings, they noted how kind and prosperous the rural Siberians were, but how harsh the soldiers and officers were.

One Decembrist's wife wrote about the amazing kindness and hospitality she found everywhere in Siberia. She was surprised by the wealth and abundance of the people. She said that Siberians were very welcoming and would not take money for food, saying "Put a candle to the God." She also noted that Siberia was a very rich country with fertile land that needed little work for a good harvest.

Some Decembrists died from diseases, and some suffered mental health problems. After their forced labor, they had to live in specific small towns. Some started businesses, which was allowed. Years later, in the 1840s, they could move to bigger cities in Siberia. In 1856, 31 years after the revolt, Alexander II pardoned them.

The Decembrists greatly helped the social life and culture in cities like Omsk, Krasnoyarsk, and Irkutsk. Their houses in Irkutsk are now museums.

Fyodor Dostoevsky was exiled to forced labor near Omsk and then to military service. He also traveled to Barnaul and Kuznetsk, where he got married.

Anton Chekhov visited Siberia in 1890, traveling to Sakhalin. He found Tomsk disappointing but called Krasnoyarsk "the most beautiful Siberian city." He noticed that despite being a place for criminals, the moral atmosphere was good, with no theft. Chekhov observed that Siberians were prosperous but needed more cultural development.

Many Poles were also exiled to Siberia. In 1866, they started the Baikal Insurrection.

The Trans-Siberian Railway

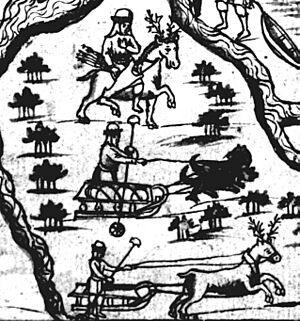

Siberia's growth was slowed by poor transportation. There were few good roads. For about five months a year, rivers were the main way to travel. In winter, people used horse-drawn sleds on frozen rivers.

The first steamboat on the Ob River was launched in 1844. Steamboat shipping really started to grow in 1857. Steamboats began operating on the Yenisei River in 1863, and on the Lena River and Amur River in the 1870s.

Western Siberia had a good river system. But the big rivers of Eastern Siberia, like the Yenisei and Lena, mostly flowed north-south. A canal connecting the Ob and Yenisei rivers was not very successful. A railroad was the real solution.

Ideas for railroads in Siberia appeared early on. One of the first was a project to connect Irkutsk to the Amur River and the Pacific Ocean. Before 1880, the government rarely approved these projects. They worried that Siberia would become too connected to the Pacific region instead of Russia.

Mainly, the fear of losing Siberia convinced Alexander II to build the railway in 1880. Construction began in 1891.

The Trans-Siberian Railroad greatly helped Siberian farming. It allowed more goods to be sent to Central Russia and Europe. It boosted areas near the railway and those connected by rivers, like the Ob and Yenisei.

Siberian farms exported a lot of cheap grain to the West. Farming in Central Russia was still affected by serfdom, which was formally ended in 1861. The fur trade was another profitable industry, adding a lot to national income.

To protect its own agriculture, the government introduced a special tariff in 1896. This changed how grain was exported. Mills appeared in Altai, Novosibirsk, and Tomsk. Many farms started producing butter. From 1896 to 1913, Siberia exported about 500,000 tonnes of grain and flour each year.

Stolypin's Resettlement Program

A big settlement program happened under Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin from 1906–1911. Central Russia's rural areas were too crowded, while eastern Siberia had fertile lands but few people.

In 1906, a decree allowed farmers to move to Asian Russia without limits and get cheap or free land. The government ran a big advertising campaign. They printed millions of brochures like "What the resettlement gives to peasants" and "How the peasants in Siberia live." Special propaganda trains were sent out, and transport trains were provided for migrants. The government also gave loans to settlers to build farms.

Not all settlers stayed; about 17.8% moved back. In total, over three million people officially moved to Siberia. From 1897 to 1914, Siberia's population grew by 73%, and the amount of land farmed doubled.

The Tunguska Event

The Tunguska Event was a huge explosion that happened near the Podkamennaya Tunguska River in Russia. It occurred on June 30, 1908.

The cause of the explosion is still debated today. Most scientists believe it was caused by a meteor air burst. This means a large meteoroid or comet broke apart and exploded in the air, about 3 to 6 miles (5 to 10 km) above Earth's surface. The object was likely a few tens of meters across.

The Tunguska event is thought to be the largest impact event on land in recent history. Because it happened in a remote area, there was little harm to people or property. It took many years for it to be properly investigated.

The first expedition arrived more than a decade later, in 1921. The Russian scientist Leonid Kulik heard local stories and thought the explosion was caused by a giant meteorite impact. He convinced the Soviet government to fund an expedition, hoping to find meteoric iron to help Soviet industry.

Kulik's team reached the site in 1927. They were surprised to find no impact crater. Instead, there was an area of scorched trees about 30 miles (50 km) wide. Some trees near the center were still standing upright but had no branches or bark. Trees farther away had been knocked down, pointing away from the center.

Siberia in the Russian Civil War

By the time of the revolution, Siberia was mostly a farming region. Only 13% of its people lived in cities and had some political knowledge. There were not strong social differences, and few city dwellers or intellectuals. This led different political groups to unite under ideas of regionalism.

The groups against the Bolsheviks could not unite. While Aleksandr Kolchak fought the Bolsheviks to remove them from the capital, local Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks tried to make peace with the Bolsheviks. Foreign allies did not get involved much.

After losing battles in Central Russia, Kolchak's forces retreated to Siberia. With resistance from Socialist-Revolutionaries and less support from allies, the anti-Bolshevik forces had to leave Omsk and then Irkutsk. Kolchak resigned under pressure.

Siberia in the Soviet Era

The 1920s and 1930s

By the 1920s, farming in Siberia was struggling. With many immigrants, land was used too much, leading to poor harvests. The civil war did not destroy farming, but it stopped food exports, which hurt farmers' incomes. New food taxes also made people unhappy. From 1920–1924, there were many anti-communist riots in rural areas, involving up to 40,000 people.

In the 1930s, the Communist Party started collectivization. This meant that well-off farming families were labeled "kulaks." Anyone who protested was also labeled this way. Many families from Central Russia were sent to Siberia's forests or swamps. Those already in Siberia had to escape or be sent to northern regions. Collectivization greatly harmed traditional farming in Siberia.

In cities, during the New Economic Policy and later, new authorities tried to build modern socialist cities. For example, the Novosibirsk theater was first designed in a modern style. It was a big project by exiled architects. Later, in the mid-1930s, it was redesigned in a more classical style.

After the Trans-Siberian Railway was built, Omsk became the largest Siberian city. But in the 1930s, the Soviets favored Novosibirsk. The first heavy industries were built in the Kuznetsk Basin (for coal mining and metallurgy) and at Norilsk (for nickel and rare-earth metals). The Northern Sea Route also began to be used for industry. At the same time, the Gulag (a system of labor camps) grew in Siberia, with many prisoners.

World War II in Siberia

In 1941, during World War II, many factories and people were moved to Siberian cities by train. They started working almost immediately to produce ammunition and military equipment.

Most of these factories stayed in Siberia after the war. They greatly increased industrial production in Siberia and became very important for many cities. The easternmost city to receive them was Ulan-Ude, as Chita was considered too close to China and Japan.

On August 28, 1941, the government ordered the relocation of many Germans from the Volga region. They were sent to different rural areas of Kazakhstan and Siberia.

By the end of the war, thousands of captured German and Japanese soldiers were sentenced to work in labor camps across Siberia. These camps were run differently from the Gulag. Although the goal was not to kill prisoners, many died, especially in winter. The work ranged from farming to building the Baikal Amur Mainline.

Industrial Expansion in Siberia

In the second half of the 1900s, the search for minerals and water power continued. Many projects were planned but were delayed by wars and changing political ideas.

The most famous project is the Baikal Amur Mainline railway. It was planned at the same time as the Trans-Siberian, but construction only began before World War II. It was paused during the war and restarted later. After Joseph Stalin's death, it was stopped again for years, then continued under Leonid Brezhnev.

Many hydroelectric power plants were built on the Angara River in the 1960s–1970s. These power plants helped create and support large factories, like the aluminum plants in Bratsk and Ust-Ilimsk. The price of electricity in the Angara basin is the lowest in Russia.

However, this development also caused environmental damage due to low production standards and overly large dams. Another power plant project in the Altai Mountains in the 1980s was canceled after public protests.

Siberia also has military-focused centers and closed cities like Seversk. By the late 1980s, a large part of the industrial production in Omsk and Novosibirsk was for military and aviation use. When state military orders collapsed, it led to an economic crisis.

The Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences connects many research institutes in the biggest cities. The largest is the Budker Institute of Nuclear Physics in Akademgorodok, a scientific town near Novosibirsk. Other scientific towns, also called "Akademgorodok," are in Tomsk, Krasnoyarsk, and Irkutsk. These places are centers for the growing IT industry, especially in Novosibirsk, which is nicknamed "Silicon Taiga."

Many Siberian companies have grown their businesses to reach all of Russia. Siberian artists and industries have also created communities that are not just centered in Moscow.

Siberia's Recent History

Until the Chita–Khabarovsk highway was finished, the Transbaikalia region was hard to reach by car. This new road will help travel to and from the Pacific regions. It will also boost settlement and industry in the less populated areas of Zabaykalsky Krai and Amur Oblast.

More transportation networks will continue to shape Siberia's development. The next project is to finish the railroad branch to Yakutsk. Another big project, suggested in the 1800s, is the Northern-Siberian Railroad. Russian Railroads also propose an ambitious project to build a railway to Magadan, the Chukchi Peninsula, and then a possible Bering Strait Tunnel to Alaska.

While Russians continue to move from Siberia to Western Russia, Siberian cities attract workers (both legal and illegal) from Central Asian countries and China.

|

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Siberia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Siberia para niños

- Age of Discovery

- Education in Siberia

- Explorers of Siberia

- Ket people

- List of Sibir khans

- Russian conquest of Siberia

- Trans-Siberian Railway

Cities in Siberia

- Timeline of Novosibirsk

- Timeline of Omsk

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |