Novgorod Republic facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lord Novgorod the Great

Господин Великий Новгород (Russian)

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1136–1478 | |||||||||||||

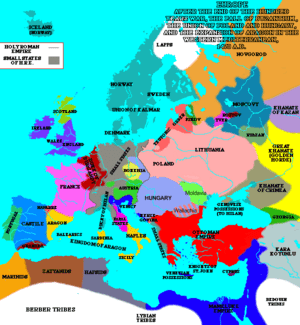

The Novgorod Republic c. 1400

|

|||||||||||||

| Capital | Novgorod | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Church Slavonic (literary) Old Novgorod dialect |

||||||||||||

| Religion | Eastern Orthodoxy | ||||||||||||

| Government | Mixed republic | ||||||||||||

| Prince | |||||||||||||

|

• 1136–1138 (first)

|

Sviatoslav Olgovich | ||||||||||||

|

• 1462–1478 (last)

|

Ivan III | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Veche Council of Lords |

||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

|

• Established

|

1136 | ||||||||||||

|

• Disestablished

|

1478 | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Today part of | Russia | ||||||||||||

The Novgorod Republic (Russian: Новгородская республика) was a powerful medieval state in northern Russia. It existed from the 12th to the 15th centuries. Its lands stretched from the Gulf of Finland in the west to the northern Ural Mountains in the east. The capital city was Novgorod.

This republic was a very important trading center. It was the easternmost trading post of the Hanseatic League, a group of powerful trading cities in Europe. The people of Novgorod were also influenced by the rich culture of the Byzantines.

Contents

What Was Novgorod Called?

The state was often simply called Novgorod or Great Novgorod (Russian: Великий Новгород, romanized: Veliky Novgorod). By the 15th century, a more formal name became common: Sovereign Lord Novgorod the Great (Russian: Государь Господин Великий Новgorod, romanized: Gosudar Gospodin Veliky Novgorod).

The terms Novgorod Land or Novgorod volost referred to the areas that belonged to Novgorod. The name Novgorod Republic is a newer term. However, people described this state as a republic as early as the 16th century.

History of Novgorod

Novgorod was first settled by different Slavic tribes. These tribes often fought each other for power. In the early 9th century, they decided to try and find a peaceful way to live together.

The Novgorod First Chronicle, an old collection of writings, says that these tribes wanted to "Seek a prince who may rule over us and judge us according to law." The people of Novgorod were also influenced by Viking culture and people.

Becoming a Republic

From the late 11th century, the people of Novgorod started to take more control over their own rules. They began to reject being politically dependent on Kiev.

The Novgorodians were among the first people in Rus' to explore the northern regions. They reached areas between the Arctic Ocean and Lake Onega. Records show that an expedition reached the Pechora River in 1032. They also started trading with the Yugra tribe as early as 1096.

By 1113, Novgorodians were paying tribute to the Grand Prince of Kiev. Over time, Novgorod's own government became stronger. Leaders like the tysiatskii and posadniki appointed local officials called boyars. These officials collected taxes and managed the territories.

Novgorod used the Baltic-Volga-Caspian trade route for both trade and to bring food from fertile regions to their city.

Challenges and Expansion

The region of Rostov-Suzdal was important because it controlled the Oka River and the Sheksna River. These rivers were vital for bringing food to Novgorod. If someone controlled these rivers, they could stop food supplies and cause a famine in Novgorod.

Because of this, Novgorod tried to invade Suzdal in 1134 but failed. They tried again and succeeded in 1149. Sometimes, Novgorod even accepted rulers from Suzdal to keep peace. However, Suzdal still blocked trade to Novgorod twice.

In 1136, the Novgorodians removed Prince Vsevolod Mstislavich. For the next 150 years, they could invite or dismiss princes. However, these decisions often depended on who was the most powerful prince in Rus' at the time.

The city of Pskov was originally part of Novgorod. But it became largely independent from the 13th century. Pskov even opened its own trading post for merchants from the Hanseatic League. Pskov's independence was officially recognized in 1348 by the Treaty of Bolotovo. However, the Archbishop of Novgorod still led the church in Pskov until 1589.

From the 12th to the 15th centuries, the Novgorodian Republic grew eastward and northeastward. They explored areas around Lake Onega, along the Northern Dvina river, and the coastlines of the White Sea. In the early 14th century, they even explored the Arctic Ocean, the Barents Sea, the Kara Sea, and the West-Siberian river Ob.

These northern lands were very important to Novgorod's economy. They were rich in fur, sea animals, and salt. Novgorod fought many wars with Moscow from the late 14th century to keep control of these lands. Losing them would mean a big economic and cultural decline for the city. In the end, Novgorod's failure to win these wars led to its downfall.

The Fall of the Republic

From the 14th century, Tver, Muscovy, and Lithuania all wanted to control Novgorod and its great wealth. At first, Novgorod preferred Muscovy as a ruler. Muscovite princes were far away and less likely to interfere too much in Novgorod's affairs. They could also help Novgorod when needed.

However, as Muscovy grew stronger, its princes became a serious threat. Leaders like Ivan Kalita and Simeon the Proud tried to limit Novgorod's independence. In 1397, Moscow even took the Dvina Lands, which were crucial for Novgorod's fur trade. These lands were returned the next year.

To resist Moscow's growing power, Novgorod's government tried to make an alliance with Poland–Lithuania. Many Novgorodian noble families, called boyars, wanted to keep the Republic independent. They feared that if Moscow conquered Novgorod, their wealth and power would be lost.

A famous story tells of Marfa Boretskaya, a powerful woman whose husband was a Posadnik. She is said to have strongly supported an alliance with Poland-Lithuania to save the Republic. She supposedly invited a Lithuanian prince, Mikhail Olelkovich, to rule Novgorod and made a deal with Casimir, the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania.

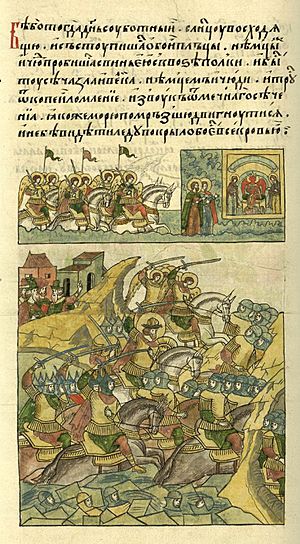

Moscow saw Novgorod's attempt to ally with Poland as a betrayal. So, Moscow went to war against Novgorod. The Moscow army won a major victory at the Battle of Shelon River in July 1471. This battle greatly reduced Novgorod's freedom, though it remained formally independent for seven more years.

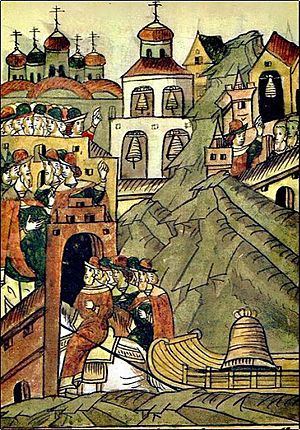

In 1478, Ivan III sent his army to take the city. He ended the veche, which was the public assembly and a symbol of Novgorod's self-governance. He also took down the Veche bell, which was an ancient symbol of the city's independence and rights. This act marked the end of the Novgorod Republic. After the takeover, Ivan III took most of Novgorod's land for himself and his supporters.

How Novgorod Was Governed

The city-state of Novgorod had a unique way of governing. It allowed a large amount of public participation, which was quite advanced for its time in Europe. The people had the power to elect city officials. They could even choose and remove their prince.

Old writings describe a "town meeting" where these decisions were made. People from all social classes attended, from the highest officials (Posadniki) to the lowest free class (Chernye Liudi).

The exact details of Novgorod's government are not fully known. However, it seems to have had a system of public assemblies called veches. It also had officials like posadniks (like a mayor), tysyatskys (originally military leaders, later judicial and commercial officials), and important noble families. The archbishops of Novgorod also played a big role.

The Archbishop's Role

Some historians believe the archbishop was the head of the government's executive branch. It's hard to know exactly what powers each official had. There might have been a "Council of Lords" (Совет Господ) led by the archbishop. This council met in the archbishop's palace.

The princes of Novgorod were always the official leaders, but their power became less important over time. The archbishop of Novgorod was a very important city official. He oversaw the church, led diplomatic missions, and handled some court cases. However, archbishops usually worked with the noble families and rarely acted alone.

The archbishop was not appointed by a higher power. Instead, he was elected by the people of Novgorod and then approved by the Metropolitan bishop of Russia. Archbishops were likely the wealthiest landowners in Novgorod. They also earned money from court fees and market fees.

The Veche and Posadniks

The Novgorod veche was a very important public assembly. The Novgorod Posadnik was another key leader. He led the veche meetings and shared power with the Prince in courts. The Posadnik also oversaw tax collection and managed the city's daily affairs. Most of the Prince's big decisions needed the Posadnik's approval.

In the mid-14th century, instead of one Posadnik, the Veche started electing six. These six posadniks held their position for life. Each year, they would choose one of themselves to be the chief Stepennoy Posadnik. Posadniks were almost always members of the boyars, the city's highest noble families.

The veche included people from the city and free people from the countryside. Historians debate whether it was truly democratic or controlled by the boyars. However, officials like posadniks, tysiatskys, and even bishops were often elected or approved by the veche.

Tradespeople and craftspeople also took part in Novgorod's political life. They were organized into five "kontsy" (meaning "ends" or boroughs) based on where they lived in the city. These ends were further divided by streets. Some street names showed that certain trades were common in those areas, like "Carpenter's End."

Merchants formed associations. The most famous were the wax traders (called Ivan's Hundred) and merchants involved in overseas trade. These groups might have influenced political decisions.

The Prince's Role

The Prince in Novgorod was a significant figure, even though his position was not passed down through his family and his power was limited. Many of Novgorod's princes were invited or dismissed by the Novgorodians themselves.

Some princes signed a special agreement called a r'ad (ряд). This contract protected the interests of the Novgorodian noble families and clearly stated the prince's rights and duties. These agreements show how Novgorod managed its relationship with invited princes from Tver, Moscow, and Lithuania.

The Prince's main job was to be a military leader. He also supported churches in the city and held court. However, a local official often ran the court if the Prince was away. The Posadnik always had to be present in court, and no court decision could be made without his approval. Also, the Prince could not give away Novgorod lands or make new laws without the Posadnik's approval. The Prince could not own land in Novgorod or collect taxes directly. He lived on money given to him by the city.

The Prince also could not send a Novgorodian citizen out of Novgorod's territory for trial or punishment. The princes had two homes: one in the Marketplace (called Yaroslav's Court) and another a few miles south of the city.

Novgorod's Economy

The economy of the Novgorodian Republic included farming and animal husbandry. For example, the archbishops of Novgorod raised horses for the army. Hunting, beekeeping, and fishing were also very common. In most parts of the republic, these activities were combined with farming.

Iron was mined near the Gulf of Finland. Staraya Russa and other places were known for their saltworks. Growing flax and hops was also very important. Products from the countryside, like furs, beeswax, honey, fish, lard, flax, and hops, were sold in the market. They were also exported to other Russian cities or abroad.

The true wealth of Novgorod came from the fur trade. The city was a major trading center between Rus' and northwestern Europe. It was at the eastern end of the Baltic trade network set up by the Hanseatic League. The lands northeast of Novgorod were so rich in fur that old travel stories claimed furry animals rained from the sky!

Novgorodian merchants traded with cities in Sweden, Germany, and Denmark. In earlier times, Novgorodians sailed the Baltic Sea themselves. There are stories of Novgorodian merchants in Gotland and Denmark. Orthodox churches for Novgorodian merchants have been found on Gotland. Similarly, merchants from Gotland had their own St. Olaf church and trading house in Novgorod.

However, the Hanseatic League later tried to stop Novgorodian merchants from trading by sea independently. They wanted to control the delivery of goods to Western European ports. Silver, cloth, wine, and herring were imported from Western Europe. Foreign coins and silver were used as money until Novgorod started making its own novgorodka coins in 1420.

Society in Novgorod

By the 14th–15th centuries, more than half of all private land in Novgorod was owned by about 30–40 noble boyar families. These large estates gave the boyars their political power. The House of Holy Wisdom, which was the main church organization, was their biggest rival in terms of land ownership. Its lands were in the richest parts of Novgorod. Other important landowners included the Yuriev Monastery, Arkazhsky Monastery, and Antoniev Monastery.

There were also zhityi lyudi, who owned less land than the boyars. Smaller landowners were called svoyezemtsy. The most common way to use labor was a system where workers paid a part of their harvest to the landowner. Slaves (called kholopy) also worked for these landowners, but their numbers slowly decreased. By the late 15th century, paying money for labor became more common.

Some historians believe that the noble landowners tried to legally tie peasants to their land. Certain types of dependent peasants, like davniye lyudi, polovniki, poruchniki, and dolzhniki, were not allowed to leave their masters. Noble families and monasteries also tried to stop other peasants from changing their landlords. However, until the late 16th century, peasants could usually leave their land in the weeks around St. George's day in the autumn.

There were about 80 major uprisings in the republic, some of which became armed rebellions. These included notable events in 1136, 1207, 1228–29, 1270, 1418, and 1446–47. These uprisings were often between different noble groups. If peasants or tradespeople revolted against the nobles, they usually wanted better rule, not to completely change the social system.

Throughout the republican period, the archbishop of Novgorod was the head of the Orthodox church. The Finnic people living in Novgorod's lands were becoming Christian. A religious group called the Strigolniki came to Novgorod from Pskov in the mid-14th century. They rejected church leaders, monks, and some church ceremonies. Another group, called the heresy of the Judaizers, appeared in Novgorod in the second half of the 15th century.

Military Power

Like other medieval states in Rus', Novgorod's military included a general call-up of citizens and the prince's personal guards (called druzhina). While all free Novgorodians could potentially be called to fight, the actual number of soldiers depended on how serious the threat was.

Professional soldiers included the guards of the archbishop and powerful noble families, as well as the soldiers protecting fortresses. Firearms were first mentioned in 1394. By the 15th century, cannons were used in fortresses and installed on ships.

Foreign Relations

During the time of Kievan Rus', Novgorod was a major trade hub. It was at the northern end of both the Volga trade route and the "route from the Varangians to the Greeks" along the Dnieper river system. Many different goods were traded along these routes with local Novgorod merchants and other traders.

Merchants from Gotland kept their Gothic Court trading house in Novgorod well into the 12th century. Later, German merchants also set up trading houses. Scandinavian royal families sometimes married Russian princes and princesses.

Relations with Hansa, Sweden, and Livonian Order

After the Great Schism (when the Christian church split), Novgorod faced conflicts from the early 13th century. They fought against Swedish, Danish, and German crusaders. During the Swedish–Novgorodian Wars, the Swedes invaded lands that had previously paid tribute to Novgorod. The Germans had been trying to conquer the Baltic region since the late 12th century.

Novgorod fought 26 wars with Sweden and 11 wars with the Livonian Brothers of the Sword. German knights, along with Danish and Swedish nobles, launched several attacks between 1240 and 1242. Novgorodian records say that a Swedish army was defeated in the Battle of the Neva in 1240. The German campaigns in the Baltic ended in failure after the famous Battle on the Ice in 1242.

After the castle of Vyborg was built in 1293, the Swedes gained a stronger position in Karelia. On August 12, 1323, Sweden and Novgorod signed the Treaty of Nöteborg. This treaty set their border for the first time.

After the Mongol Invasion

The Novgorod Republic was lucky because it was not directly conquered by the Mongol invasion. It was the only Rus' principality that avoided this. In 1259, Mongol tax-collectors came to Novgorod. This caused some trouble in the city. Alexander Nevsky had to punish some city officials for not obeying him and his Mongol overlords.

In the 14th century, raids by Novgorod pirates, called ushkuiniki, caused fear as far away as Kazan and Astrakhan. These pirates helped Novgorod in its wars with Muscovy.

Novgorod's Culture

Art and Icons

The Novgorod Republic was known for its high level of culture, especially compared to other Russian regions like Suzdal. Many important Eastern artworks from this period came from Novgorod. People in Novgorod created a lot of art, especially religious icons. This was possible because the economy was doing very well.

Not only did rich noble families order icons, but artists also had support from wealthy merchants and skilled craftspeople. Icons became so popular in Novgorod that by the late 13th century, even ordinary citizens could afford one. Icons were also made for export, as well as for churches and homes. However, only a small number of icons made in Novgorod from the 12th to the 14th centuries have survived.

The icons that remain show a mix of traditional Rus' style, Byzantine style (which was popular in Kiev), and European Romanesque and Gothic styles. Artists and their audiences in Novgorod liked saints who protected things related to the economy. For example, Prophet Elijah was seen as the lord of thunder who brought rain for farmers' fields. Saint George, Saint Blaise, and Saints Florus and Laurus protected fields and animals. Saint Paraskeva Pyatnitsa and Saint Anastasia protected trade and merchants. Saint Nicholas was the patron of carpenters and protected travelers and those in need. Both Saint Nicholas and Prophet Elijah also protected against fires, which were common in the city and fields.

These saints remained popular throughout the Republic's history. But in the early 14th century, another icon became important: the Virgin of Mercy. This icon celebrates the Virgin Mary appearing to Andrew Yurodivyi and Epifanii, where she prays for all people. After Moscow conquered Novgorod in 1478, the unique art style of Novgorod largely ended. Moscow introduced a more uniform way of creating icons across Russia.

Architecture and City Layout

The Volkhov River divided the city of Novgorod into two parts. The commercial side, with the main market, was on one side of the river. The St. Sophia Cathedral and an old kremlin (fortress) were on the other side. The cathedral and kremlin were surrounded by strong city walls, which included a bell tower.

Novgorod was full of churches and monasteries. The city was crowded, with a large population of about 30,000 people. Wealthy families (boyars, artisans, and merchants) lived in big houses inside the city walls. Poorer people lived wherever they could find space. The streets were paved with wood. The city also had a wooden water-pipe system, which was a Byzantine idea to help prevent fires.

The architecture of Novgorod was influenced by both Byzantine style (known for large domes) and European Romanesque style. Many rich families paid for churches and monasteries to be built in the city. About 83 churches, mostly made of stone, were active during this time.

There were two main styles of churches in Novgorod. The first had a single apse (a rounded part of the church) and a slanted roof. This style was common across Russia. The second, called the Novgorodian style, had three apses and roofs with arched gables. This Novgorodian style was popular in the early and late years of the Republic. It was revived later as a way to show independence from Moscow. Inside the churches, there were icons, wood carvings, and church plates. The first known one-day votive church was built in Novgorod in 1390 to stop a pandemic. Several others were built until the mid-16th century. Since they were built in one day, they were made of wood, small, and simple.

Literature and Literacy

Old writings called chronicles are the earliest type of literature from Novgorod. The oldest is the Novgorod First Chronicle. Other types of writings appeared in the 14th and 15th centuries. These included travel diaries, like the story of Stefan the Novgorodian's trip to Constantinople for trade. There were also legends about local leaders, saints, and Novgorod's wars. Many traditional Russian epic poems, called bylinas, are set in Novgorod. Their main characters include a merchant named Sadko and a brave adventurer named Vasily Buslayev.

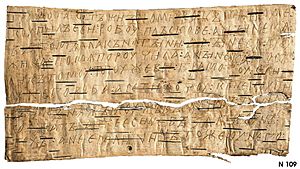

Historians generally believe that the Novgorod Republic had a very high level of literacy for its time. Archaeologists have found over a thousand birch-bark texts in old Rus' towns, all dating from the 11th to the 15th centuries. About 950 of these texts were found in Novgorod. Experts think that as many as 20,000 similar texts might still be buried, and many more were lost in fires.

People from all social classes in Novgorod wrote these texts, from noble families to peasants, artisans, and merchants. Even women wrote a lot of these documents. This collection of birch-bark texts includes religious documents, writings from the city's archbishops, business messages, and travel stories, especially about religious journeys. The people of Novgorod wrote in a realistic and practical way. Besides the birch-bark texts, archaeologists also found the oldest surviving Russian manuscript in Novgorod: three wax tablets with Psalms 67, 75, and 76, dating from the early 11th century.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: República de Nóvgorod para niños

In Spanish: República de Nóvgorod para niños

- Pskov Republic

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |