Ainu people facts for kids

| アィヌ | |

|---|---|

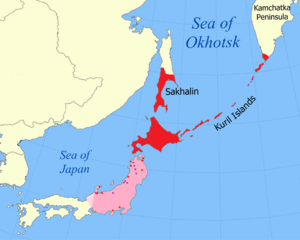

Historical homeland and distribution of Ainu people

|

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 11,450 surveyed in 2023 | |

| 300 (2021 census) | |

| Languages | |

| Ainu languages, Japanese, Russian | |

| Religion | |

| Ainu folk religion, Animism, Japanese Buddhism, Shinto, Russian Orthodoxy | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Jomon people, Satsumon, Okhotsk, Matagi, Emishi, Nivkh | |

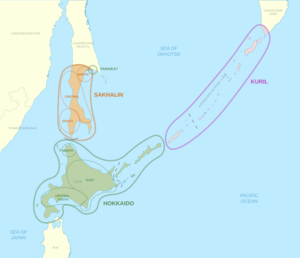

The Ainu are an indigenous group of people. They live in northern Japan and southeastern Russia. This includes Hokkaido and parts of Honshu, like the Tōhoku region. They also live around the Sea of Okhotsk, such as Sakhalin, the Kuril Islands, and the Kamchatka Peninsula. The Ainu have lived in these areas, which they call "Ainu Mosir" (meaning 'the land of the Ainu'), for a very long time. They were there before the modern Japanese and Russians arrived.

Official surveys in 2023 showed about 11,450 Ainu in Hokkaido. In Russia, about 300 Ainu were counted in 2021. However, many people of Ainu descent might not know their background. This is because the Ainu were largely absorbed into Japanese society.

The Ainu are one of the few native ethnic groups in Japan. They faced forced assimilation and colonization by the Japanese. This started as early as the 18th century. In the 19th century, during the Meiji Restoration, Japanese policies forced Ainu people off their land. This made them give up their traditional ways of life, like hunting and fishing. They were not allowed to practice their religion. They had to go to Japanese-language schools, where speaking the Ainu language was forbidden. In recent years, there have been efforts to bring the Ainu language back.

Contents

- Understanding the Name "Ainu"

- Ainu History: A Journey Through Time

- Ainu Origins: Where Did They Come From?

- Ainu Culture: Traditions and Daily Life

- Ainu Organizations and Museums

- Ainu Population: How Many Ainu Are There?

- Images for kids

- See also

Understanding the Name "Ainu"

The most common name for these people is Ainu. In the Ainu language, Ainu means 'human'. It is used to describe people, unlike kamuy, which means 'divine beings' or 'gods'. The Ainu also call themselves Utari, meaning 'comrades' or 'people'. Both names are used in official documents today.

The name Aino first appeared in a Latin book in 1591. This book called Hokkaido Aino moxori, or Ainu mosir, meaning 'land of the Ainu'. The terms Aino and Ainu became common in the early 1800s. Before the late 1700s, Europeans and Japanese did not see the Ainu as a separate ethnic group.

The Ainu were also called Kuye by their neighbors. The Qing dynasty in China called Sakhalin "Kuyedao," meaning "island of the Ainu." The word Kuye is likely related to kuyi. This was the name given to the Sakhalin Ainu by their Nivkh and Nanai neighbors.

An old Japanese name for the Ainu was Emishi. This term was sometimes used to mean "barbarian" and referred to their hairiness. Today, the Ainu consider this term insulting.

Ainu History: A Journey Through Time

The Ainu are seen as the original people of Hokkaido, southern Sakhalin, and the Kurils. Place names in the Ainu language show that they lived in many parts of northern Honshu. It is also possible that Ainu speakers lived in the Amur region. This is suggested by Ainu words found in the Uilta and Ulch languages.

The ancestors of the Ainu, called Emishi, came under Japanese rule in the 9th century. They were then pushed to the northern islands.

Developing Ainu Culture (Nibutani Period)

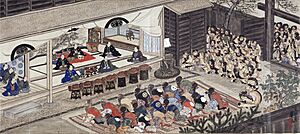

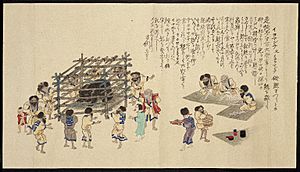

Around the 13th century, the Ainu developed their own unique culture. They traded between Honshu and northeast Asia. This time is known as the Ainu Culture period or Nibutani period.

During this time, the Wajin (ethnic Japanese) and the Ainu of Ezo (now Hokkaido) began to interact a lot. The Ainu lived as hunter-gatherers, getting food mainly by hunting and fishing. Their religion was based on nature.

After the Mongols conquered the Jin dynasty, the Ainu in Sakhalin faced attacks from the Nivkh and Udege peoples. The Mongols set up a post in Nurgan in 1263. They forced both groups to submit. In 1264, the Sakhalin Ainu attacked the Nivkh people. This led to the Mongols invading Sakhalin.

The Nivkh people saw their surrender to the Mongols as an alliance against the Ainu. The Mongols attacked the Ainu in 1264. The Sakhalin Ainu fought back but were defeated by 1308. They then paid tribute to the Mongol Yuan dynasty.

The Chinese Ming dynasty (1368–1644) also had influence over Sakhalin. From 1409 to 1411, the Ming set up a military outpost near Tyr, Russia. There is some evidence that a Ming admiral reached Sakhalin in 1413. He gave Ming titles to a local Ainu leader.

The Ming dynasty gave administrative jobs to Ainu leaders. These jobs were passed down through families. In return for tribute, the Ming gave them silk uniforms.

Nivkh women in Sakhalin married Han Chinese Ming officials. Chinese culture and religion, like Chinese New Year and dragon symbols, spread among the Ainu and other native groups. These groups also started using Chinese goods like iron pots, silk, and cotton. They also adopted farming.

The Manchu Qing dynasty took power in China in 1644. They called Sakhalin "Kuyedao" (island of the Ainu). The Qing first influenced Sakhalin after the 1689 Treaty of Nerchinsk. This treaty set the border between the Qing and Russian Empires. The Qing then sent forces to the Amur estuary. They demanded that people, including the Sakhalin Ainu, pay tribute. The Qing sent officials to Sakhalin to collect fur tribute. They also gave rewards.

By the 1730s, the Qing appointed Ainu leaders as "clan chief" or "village chief." In 1732, 6 clans and 148 households in Sakhalin paid tribute. Manchu officials gave rice, salt, and gifts to tribute missions. This helped bring stability and trade to the region.

Japanese Influence and Colonization

In 1635, a Japanese leader from Matsumae Domain sent an expedition to Sakhalin. One explorer stayed there in the winter of 1636. The Tokugawa bakufu (Japanese government) gave the Matsumae clan special rights to trade with the Ainu. Japanese merchants then leased these trading rights. This led to more contact between Japanese and Ainu people. Ainu groups competed to get goods from the Japanese. Diseases like smallpox also reduced the Ainu population. A Japanese settlement was set up in southern Sakhalin in 1679.

By the early 1800s, Japanese influence in southern Sakhalin grew. Most Ainu stopped paying tribute to the Qing dynasty. The Matsumae clan was supposed to govern Sakhalin. Instead, they took Chinese silk from the Ainu and sold it in Honshu. To get Chinese silk, the Ainu went into debt. The Tokugawa government realized they could not rely on the Matsumae. So, they took control of Sakhalin in 1807.

From 1799 to 1806, the Tokugawa shogunate directly controlled southern Hokkaido. Japan claimed Sakhalin in 1807. During this time, Ainu women were forced to marry Japanese men. Ainu men were sent away for years of service. These policies, along with smallpox, greatly reduced the Ainu population. In the 18th century, there were 80,000 Ainu. By 1868, there were only about 15,000 in Hokkaido, 2,000 in Sakhalin, and 100 in the Kuril Islands.

Even with their growing influence, Japan could not control all trade with the Ainu. Santan traders, mainly Ulchi, Nanai, and Oroch from the Amur River, traded with the Ainu. This happened especially in northern Hokkaido. Santan traders sometimes kidnapped Ainu women to be their wives. This led Japan to increase its presence. They believed a trade monopoly would better protect the Ainu.

Japanese Annexation of Hokkaido

In 1869, the Japanese government created the Hokkaidō Development Commission. This was part of the Meiji Restoration. The goal was to develop Hokkaido to defend against Russia. It also provided jobs for former samurai. Finally, it aimed to get natural resources for Japan's growing economy.

The Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1875) gave the Kuril Islands to Japan. This included their Ainu inhabitants. In 1899, Japan passed a law calling the Ainu "former aborigines." The idea was to make them assimilate. This law took Ainu land and put it under Japanese control. The Ainu were also given Japanese citizenship. This effectively denied them their status as an indigenous group.

The Ainu went from being isolated to having their land, language, and customs taken over by the Japanese. Their land was given to Japanese settlers for farming. This was called "colonization." Factories and mines were built, creating roads and railways. The Ainu were told to stop religious practices like animal sacrifice and tattooing. The same law applied to Ainu in Sakhalin after Japan took it over.

Life After Annexation: Assimilation and Discrimination

Historically, the Ainu faced economic and social discrimination. The Japanese government and people often saw them as primitive. Most Ainu were forced to be laborers during the Meiji Restoration. This was when Hokkaido became part of the Japanese Empire. Their traditional lands were privatized. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the Japanese government denied the Ainu their cultural practices. This included hunting, gathering, and speaking their language.

The 1899 Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection Act denied Ainu cultural practices. This law aimed to fully integrate the Ainu into Japanese society. It also aimed to erase Ainu culture and identity. The Ainu's forced role as manual laborers led to ongoing discrimination.

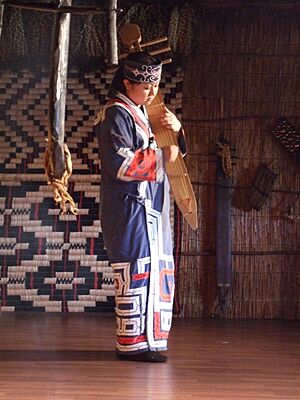

Marriage between Japanese and Ainu was encouraged by the Ainu. This was to reduce discrimination against their children. Many Ainu today look like their Japanese neighbors. However, some Ainu-Japanese are interested in traditional Ainu culture. For example, Oki, whose father was Ainu, became a musician. He plays the traditional Ainu instrument, the tonkori. Many small towns in Hokkaido, like Nibutani, still have ethnic Ainu people.

Christian missionaries began working among the Ainu in the 1870s. Missionaries like John Batchelor wrote a lot about Ainu beliefs and daily life. His books include old photos of Japanese and Ainu people.

Standard of Living and Recognition

Discrimination led to lower education and income for Ainu people. In 1993, Ainu in Hokkaido received welfare payments at a much higher rate than other residents. They also had lower rates of going to high school and college. Because of this gap, activists asked the Japanese government to study the Ainu's standard of living. The government began surveys in 2015.

The Ainu's existence challenged the idea that Japan was ethnically uniform after World War II. After 1945, Japanese governments promoted a single Japanese identity. They denied that other ethnic groups existed in Japan.

The Ainu were first recognized as an indigenous people in 1997. This started the process of claiming indigenous rights. In 2008, the National Diet of Japan passed a resolution. It called for the government to recognize the Ainu as indigenous people.

In 2019, the Diet finally passed a law recognizing the Ainu as an indigenous people of Japan. Despite this, some Japanese politicians still say that ethnic sameness is key to Japan's identity.

Ainu Origins: Where Did They Come From?

The Ainu are believed to be descendants of the Jōmon people. These were indigenous hunter-gatherers who lived in Japan during the Jōmon period (around 14,000 to 300 BCE).

The exact origins of the early Ainu are still being studied. However, it is generally agreed they are linked to the Satsumon culture. This culture existed during the Epi-Jōmon period. Later, the nearby Okhotsk culture also influenced them. The Ainu culture might be better described as a "cultural complex." This means it includes different regional Ainu groups.

One of their legends, called Yukar Upopo, says that "The Ainu lived in this place a hundred thousand years before the Children of the Sun came."

Historically, the Ainu economy included farming. They also relied on hunting, fishing, and gathering.

Most historians connect the Ainu with the Satsumon culture. This culture was found from northern Honshu to Hokkaido. Linguists believe Ainu dialects came from Satsumon. They also see links to cultures in Central or Northern Honshu. This is supported by Ainu words found in Eastern Old Japanese. There is also a likely distant link between the Ainu and the Emishi.

The Okhotsk culture also played a role in forming the Ainu culture. Okhotsk remains show connections to the modern Nivkh people of northern Sakhalin. They also show links to the Jōmon peoples of Japan. This suggests that Okhotsk society was made up of different groups. Satsumon pottery has been found at Okhotsk sites. This shows a complex network of contacts around the Sea of Okhotsk.

The Ainu culture mainly developed from the Satsumon culture. It later received influences from the Okhotsk culture. This happened through cultural contacts in northern Hokkaido. This view has been confirmed by recent studies.

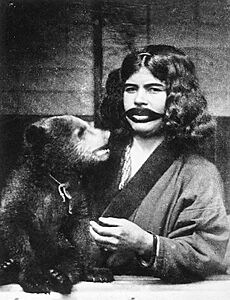

Archaeologists believe that bear worship was shared by the Okhotsk people. This religious practice is common among northern Eurasian groups like the Ainu. However, no signs of bear worship have been found from the Jomon and Epi-Jomon periods. This suggests the Okhotsk culture contributed to the Ainu culture.

Ainu and the Emishi People

The idea that the ancient Emishi were exactly the same as the Ainu has largely been disproven. However, their exact relationship is still debated. It is agreed that some Emishi spoke Ainu languages. They were also ethnically related to the Ainu. The Emishi might have included non-Ainu groups. These could be groups distantly related to the Ainu or early Japanese-speakers.

The Emishi had clear cultural links to the Ainu of Hokkaido. Place names in the Ainu style across Tohoku suggest that the Emishi, like the Ainu, came from the Epi-Jōmon tribes. They likely spoke Ainu-related languages.

In the Nara period (710–794), "Emishi" referred to people in the Tohoku region. Their lifestyle and culture were very different from the Yamato people. It was a cultural and political term, not a racial one.

From the mid-Heian period, Emishi who were not under Japanese rule were called "northern Emishi." They began to be called "Ezo."

The first written mention of "Ezo," believed to be Ainu, is from 1356. Indeed, Ainu have lived in Sakhalin, the Kuril Islands, Hokkaido, and northern Tohoku since the 13th century.

Ainu Culture: Traditions and Daily Life

Traditional Ainu culture is quite different from Japanese culture. According to Tanaka Sakurako, Ainu culture is part of a larger "northern circumpacific region." This includes indigenous cultures of Northeast Asia and North America. Ainu culture developed from the 13th century to today. Most Ainu in Japan now live lives similar to ethnic Japanese due to assimilation policies. However, many still keep their Ainu identity and respect traditional Ainu ways, called "Ainu puri." The unique Ainu patterns (Ainu mon'yō) and oral stories (Yukar) are recognized as Hokkaido Heritage.

Ainu Language: Keeping It Alive

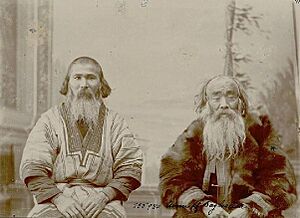

In 2008, it was estimated that fewer than 100 people still spoke the Ainu language. In 1993, a linguist said there were fewer than 15 speakers, calling the language "almost extinct." Because so few native speakers are left, studying the Ainu language is hard. It relies mostly on old research. Historically, the Ainu language was important. Early Russian and Japanese officials used it to talk to each other and the Ainu.

Despite the small number of native speakers, there is a strong effort to revitalize the language. This is happening mainly in Hokkaido. Ainu oral stories have been recorded to save them for the future. They are also used to teach the language. As of 2011, more people were learning Ainu as a second language.

The return of Ainu culture and language is thanks to Shigeru Kayano. He was an Ainu folklorist, activist, and former Japanese politician. He opened an Ainu language school in 1987.

Some researchers have tried to show that Ainu and Japanese languages are related. However, modern scholars say their relationship is only due to contact, like borrowing words. No one has widely accepted a link between Ainu and any other language. Linguists now classify Ainu as a language isolate. This means it is not related to any other known language family. Most Ainu people speak Japanese or Russian.

The Ainu language has no original writing system. Historically, it was written using Japanese kana or Russian Cyrillic. As of 2019, it is usually written in katakana or the Latin alphabet.

Many Ainu dialects are not easily understood by speakers of other dialects. However, all Ainu speakers understand the classic Ainu language of the Yukar. This is a form of Ainu epic. Without a writing system, the Ainu were great storytellers. The Yukar and other stories were memorized. They were told at gatherings that could last for hours or even days.

Ainu grammar uses postpositions. These come after the word they modify. For example, instead of "to the house," it would be "house to." An Ainu sentence can have many added sounds or affixes. These represent nouns or ideas.

Ainu Social Structure

Ainu society was traditionally organized into small villages called kotan. These were usually by rivers or seashores where food was easy to find. Salmon traveling upstream in rivers were especially important. In later times, Ainu were forced to move their kotan near Japanese fishing grounds to work. This caused traditional kotan to disappear. Larger villages formed around fishing areas. The Ainu social structure included chiefs. However, they did not handle legal matters. Instead, many community members would judge criminals. There was no death penalty or imprisonment. Beating was considered enough punishment.

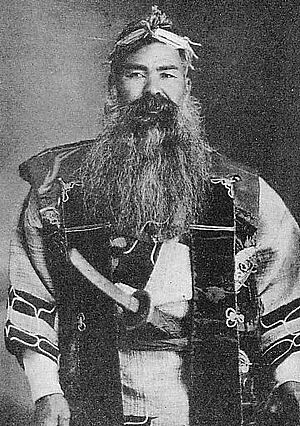

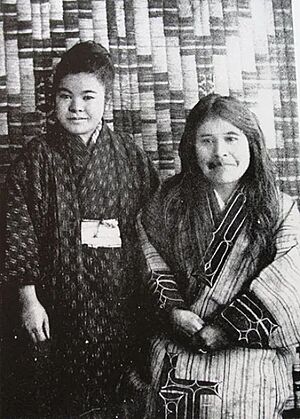

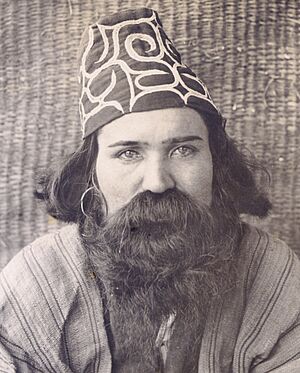

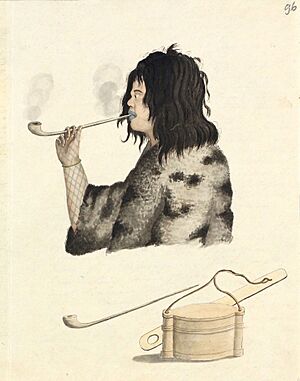

Appearance and Traditional Dress

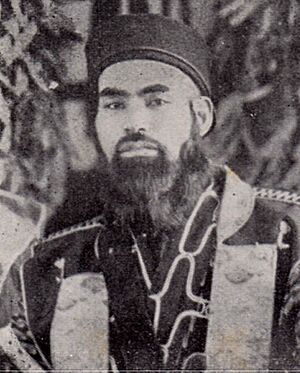

Ainu men traditionally grow full beards and moustaches after a certain age. Men and women cut their hair level with their shoulders on the sides. The back is trimmed in a semi-circle. Women tattoo their mouths and sometimes their forearms. Mouth tattoos start young with a small spot on the upper lip. They gradually get bigger. Soot from a pot over a birch bark fire is used for the color.

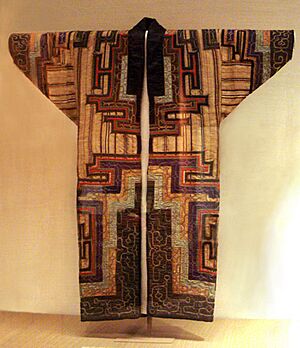

Traditional Ainu clothes are robes made from the inner bark of the elm tree. These are called attusi or attush. They are simple, short robes with straight sleeves. They wrap around the body and are tied with a band at the waist. The sleeves end at the wrist or forearm. The robes usually reach the calves. Women also wear an undergarment made of Japanese cloth.

In winter, animal skins are worn. Leggings are made of deerskin. In Sakhalin, boots are made from dog or salmon skin. Ainu culture sees earrings, traditionally made from grapevines, as for both men and women. Women also wear a beaded necklace called a tamasay. Modern craftswomen make and embroider traditional clothes. These can be very expensive.

Traditional Ainu Homes

Their traditional homes are huts with reed roofs. The largest are about 20 feet square. They have no inner walls and a fireplace in the center. There is no chimney, just a hole in the roof corner. One window is on the eastern side, with two doors. The village head's house is used for public meetings.

Another traditional Ainu house is called a chise. The chise is usually built facing east to west or parallel to a river. The entrance is on the west side and is also used for storage. It has three windows. The sacred rorun-puyar window is on the east side. Gods enter and leave through this window. Ceremonial tools are also taken in and out through it. The Ainu consider this window sacred and never look in through it. A chise has a fireplace near the entrance. A husband and wife traditionally sit on the left side of the fireplace (called shiso). Children and guests sit facing them on the right side (called harkiso). The chise has a platform for valuables called iyoykir behind the shiso. The Ainu place sintoko (hokai) and ikayop (quivers) there.

Ainu Cuisine: Food from Nature

Traditional Ainu cuisine includes meat from bears, foxes, wolves, badgers, oxen, and horses. They also eat fish, fowl, millet, vegetables, herbs, and roots. The Ainu traditionally never eat raw fish or meat. They always boil or roast it. They also grew crops like millet, which was used to make a type of sake called "tonoto" for ceremonies.

Salmon was very important. It was called kamuy chep (god's fish) or shipe (true food). In autumn, large amounts of salmon were caught and dried to preserve them. This was a main food source and a major trade item with the Japanese. The Ainu also used the bulbs of a plant called Cardiocrinum cordatum (turep). They extracted and preserved starch from it. This tradition made it easy for them to use potatoes when they were introduced. Ainu cuisine is not common outside Ainu communities. Only a few restaurants in Japan serve traditional Ainu dishes.

Hunting and Fishing: Sustaining Life

The Ainu traditionally hunt from late autumn to early summer. This is when plants have withered, and animals are easier to find. A village usually has its own hunting ground. Sometimes, several villages share a hunting territory, called an iwor. Strict rules were in place to prevent outsiders from trespassing. The Ainu traditionally hunt Ussuri brown bears, Asian black bears, Ezo deer, hares, red foxes, Japanese raccoon dogs, and other animals. Ezo deer and salmon are very important food sources. The Ainu also hunt sea eagles, ravens, and other birds. They hunted eagles for their tail feathers, which they traded with the Japanese. Historically, the Ainu hunted sea-otters and traded their furs.

The Ainu hunted with arrows and spears that had poison on their tips. They got this poison, called surku, from the roots and stalks of aconites. The recipe for this poison was a family secret. They made the poison stronger with other ingredients. They also used stingray stingers. They traditionally hunt in groups with dogs. Before hunting, especially for bears, they might pray to the Kamuy-huci, the house guardian goddess. They would ask for a good catch and pray to the god of mountains for safe hunting. The Ainu traditionally hunt bears during the spring thaw. At this time, bears are weak after hibernation. Ainu hunters catch bears that are hibernating or have just left their dens. When they hunt bears in summer, they use a spring trap with an arrow, called an amappo. The Ainu usually use arrows to hunt deer. They also drive deer into a river or sea and shoot them with arrows. For a large catch, a whole village would drive a herd of deer off a cliff and kill them with clubs.

Fishing: A Key Resource

Fishing is very important to Ainu culture. They mostly catch trout in summer and salmon in autumn. They also catch Japanese huchen, dace, and other fish. Spears called marek were often used. Other methods included tesh fishing, uray fishing, and rawomap fishing. Many villages were built near rivers or along the coast. Each village or person had a specific river fishing territory. Outsiders could not fish there without asking the owner.

Ainu Ornaments and Adornments

Traditionally, Ainu men wear a crown called a sapanpe for important ceremonies. Sapanpe are made from wood fiber with bundles of partially shaved wood. The crown has wooden figures of animal gods and other decorations in the center. Men carry an emush (ceremonial sword) attached to their shoulders with a strap called an emush-at.

Ainu women traditionally wear matanpushi, which are embroidered headbands. They also wear ninkari, which are metal earrings with balls. Matanpushi and ninkari were originally worn by men too. Additionally, aprons called maidari are now part of women's formal clothes. However, some old records say that men also wore maidari. Women sometimes wear a bracelet called a tekunkani.

Women may wear a necklace called a rektunpe. This is a long, narrow strip of cloth with metal plaques. They may also wear a necklace called a tamasay or shitoki, usually made from glass beads. Some glass beads came from trade with other parts of Asia. The Ainu also got glass beads secretly made by the Matsumae clan.

Ainu Traditions and Customs

The Ainu people have different types of marriage. A child is traditionally promised in marriage by their parents and the parents of their future spouse. Or, a go-between might arrange it. When the couple is old enough to marry, they are told who their spouse will be. There are also traditional marriages based on the couple's own choice. In some areas, when a daughter is old enough to marry, her parents let her live in a small room called a tunpu. This room is attached to the south wall of the house. The parents choose her husband from the men who visit her.

The age for marriage is 17 to 18 for men and 15 to 16 for women. At these ages, both are considered adults. Women are traditionally tattooed.

When a man proposes to a woman in the traditional way, he visits her house. She gives him a full bowl of rice. He eats half and returns the rest to her. If she eats the remaining rice, she accepts his proposal. If she puts it aside, she rejects it. When a man and woman get engaged, they exchange gifts. The man sends her a small engraved knife, a workbox, and other gifts. She sends him embroidered clothes and other handmade items.

Old, worn-out clothing fabric is used for baby clothes. This is because soft cloth is good for their skin. Also, worn-out material was thought to protect babies from illness gods and demons. Before a baby is breast-fed, they are given a special drink. This is to remove impurities. Children are raised almost naked until they are about four or five years old. Even when they wear clothes, they do not wear belts. The front of their clothes is left open. Later, they wear plain bark clothes, like attush, until they become adults.

Ainu babies are traditionally not given permanent names when they are born. Instead, they are called by different temporary names until they are two or three. Some children are named based on their behavior. Others are named after important events or their parents' wishes for their future. When children are named, they are never given the same names as others.

Men traditionally wear loincloths. They have their hair styled properly for the first time at age 15 to 16. Women are also considered adults at 15 to 16. When women reached 12 or 13, their lips, hands, and arms were traditionally tattooed. When they reached 15 or 16, their tattoos were finished. This showed they were ready for marriage.

Ainu Religion: Spirits and Rituals

The Ainu are traditionally animists. They believe that everything in nature has a kamuy (spirit or god) inside. The most important kamuy include:

- Kamuy-huci, goddess of the hearth

- Kim-un-kamuy, god of bears and mountains

- Repun Kamuy, god of the sea, fishing, and marine animals

- Kotan-kar-kamuy, believed to be the creator of the world

Ainu craftspeople believed that anything made with deep care was filled with spirit and became a kamuy. They also believed that ancestors and family power could protect them from bad influences. This was done through certain patterns in their art.

The Ainu religion has no professional priests. The village chief performs necessary religious ceremonies. Ceremonies involve offering sake, saying prayers, and offering willow sticks with wooden shavings. These sticks are called inaw (singular) and nusa (plural).

They are placed on an altar to "send back" the spirits of killed animals. Ainu ceremonies for sending back bears are called Iyomante. The Ainu people thank the gods before eating. They pray to the fire deity when they are sick. Traditional Ainu belief says their spirits are immortal. Their spirits will be rewarded by going to kamuy mosir (Land of the Gods).

The Ainu are part of a larger group of indigenous people who practice "arctolatry," or bear worship. The Ainu believe the bear is very important. It is Kim-un Kamuy's way of giving the gift of bear hide and meat to humans.

John Batchelor reported that the Ainu see the world as a round ocean with many islands floating on it. This is because the sun rises in the east and sets in the west. He wrote that they believe the world rests on a large fish. When it moves, it causes earthquakes.

Ainu who have joined mainstream Japanese society have adopted Buddhism and Shintō. Some northern Ainu became members of the Russian Orthodox Church. In areas like Shikotan, some churches have been built. Some Ainu have accepted Christianity. However, many Ainu have kept their faith in their traditional gods.

A 2012 survey found that many Ainu are members of their family's religion, which is Buddhism. However, like the Japanese, they often do not strongly identify with one religion. Buddhist and traditional beliefs are both part of their daily lives.

Ainu Rituals

The Ainu religion is based on interactions between humans and kamuy. Within all living things, natural forces, and objects, there is a ramat (sacred life force). This is part of a greater kamuy. Kamuy are gods or spirits that visit the human world in temporary physical forms. When the physical form dies or breaks, the ramat returns to the kamuy. It leaves its physical form as a gift to humans. If humans treated the form and kamuy with respect, the kamuy would return. Because of this, the Ainu lived with deep respect for nature. They hoped the kamuy would return. The Ainu believed that the kamuy gave humans tools and knowledge. So, they deserved respect and worship. Daily practices included hunting, gathering, and harvesting in moderation. This was to avoid disturbing the kamuy. The Ainu often made offerings of an inau (sacred shaved stick) and wine to the kamuy. They also built sacred altars called nusa. These were separated from the main house and raised storehouses. They often held outdoor rituals.

The Ainu had a ritual to send kamuy back to the spirit world. This was called Omante. A bear cub would be captured alive during hibernation. It would be raised in the village like a child. Women would care for the cubs as if they were their own children. Once the bears grew up, they would hold another ritual every 5 to 10 years. This was called Iomante. People from nearby villages were invited to celebrate. Villagers would send the bear back to the spirit world. They would gather around it and use special ceremonial arrows to shoot it. Afterward, they would eat the meat. However, in 1955, this ritual was outlawed as animal cruelty. In 2007, it became allowed again due to its cultural importance. The ritual has since been changed. It is now an annual festival. The festival starts at sunset with a torch parade. A play is performed, followed by music and dancing.

Other rituals were for things like food and illness. The Ainu had a ritual to welcome salmon. They prayed for a big catch. Another ritual thanked the salmon at the end of the season. There was also a ritual to keep away kamuy that brought diseases. They used strong-smelling herbs in doorways and windows. This was to turn away disease kamuy. Like many religions, the Ainu also prayed and made offerings to their ancestors. They would also pray to the fire kamuy to deliver their offerings of snacks, fruit, and tobacco.

Dancing in Ainu Rituals

Traditional dances are performed at ceremonies and celebrations. Dancing is part of new cultural festivals. It is also done privately in daily life. Ainu traditional dances often involve large circles of dancers. Sometimes, onlookers sing without instruments. In rituals, these dances are personal. They involve the calls and movements of animals or insects. Some, like the sword and bow dances, were rituals to worship and thank nature. This was to thank the gods they believed were around them. There was also a dance in Iomante that copied the movements of a living bear. However, some dances are made up on the spot just for fun. Overall, Ainu traditional dancing strengthened their connection to nature and the religious world. It also linked them to other Arctic cultures.

Ainu Funerals

Funerals included prayers and offerings to the fire kamuy. There were also sad poems expressing wishes for a smooth journey to the next world. Items to be buried with the dead were first broken. This was to let spirits be released and travel to the afterlife together. Sometimes, a burial was followed by burning the dead person's home. If someone died unnaturally, there would be a speech against the gods.

In the afterlife, recognized ancestral spirits could move through and influence the world. However, neglected spirits would return to the living world and cause bad luck. A family's prosperity in the afterlife depended on prayers and offerings from living descendants. This often led Ainu parents to teach their children to care for them in the afterlife.

Ainu Organizations and Museums

Most Hokkaido Ainu are members of a group called the Hokkaido Ainu Association. The organization changed its name to Hokkaidō Utari Association in 1961. This was because the word Ainu was often used in a bad way by non-Ainu Japanese. It changed back to the Hokkaido Ainu Association in 2009. This happened after a new law about the Ainu was passed. The organization was first controlled by the government to help Ainu assimilate. Now, it is run only by Ainu people and works mostly independently.

Other important groups include The Foundation for Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture (FRPAC). This was set up by the Japanese government in 1997. There is also the Hokkaidō University Center for Ainu and Indigenous Studies, started in 2007. Many museums and cultural centers also exist. Ainu people living in Tokyo have also created a strong political and cultural community.

Since late 2011, the Ainu have worked with the Sámi people of northern Europe. Both the Sámi and the Ainu are part of an organization for Arctic indigenous peoples.

Currently, there are several Ainu museums and cultural parks. Some of them are:

- National Ainu Museum

- Kawamura Kaneto Ainu Museum

- Ainu Kotan

- Ainu Folklore Museum

- Hokkaido Museum of Northern Peoples

- Nibutani Ainu Culture Museum

- Shinhidaka Ainu Museum

Ainu Population: How Many Ainu Are There?

The Ainu population during the Edo period was at most 26,800. It has since decreased, partly due to infectious diseases.

According to the 1897 Russian census, 1,446 Ainu native speakers lived in Russian territory.

Today, there is no Ainu category in the Japanese national census. No official count has been done by national groups. So, the exact number of Ainu people is unknown. However, several surveys give an idea of the total population.

A 2006 Hokkaido Agency survey found 23,782 Ainu people in Hokkaido. The survey defined "Ainu" as "a person who seems to have inherited the blood of Ainu" or "the same livelihood as those with marriage or adoption."

A 1971 survey estimated an Ainu population of 77,000. Another survey suggested 200,000 Ainu living in Japan. However, no other surveys support this high estimate.

Many Ainu live outside Hokkaido. A 1988 survey estimated that 2,700 Ainu lived in Tokyo. A 1989 report suggested that the Ainu population in the Tokyo area alone was more than 10,000. This is more than 10% of Ainu living in Hokkaido.

In 1992, it was reported that a descendant of Kuril Ainu lived in Poland. However, there are also signs they might be Aleut descendants. On the other hand, the children of Polish anthropologist Bronisław Piłsudski, a leading Ainu researcher, were born in Japan.

According to a 2017 survey, the Ainu population in Hokkaido is about 13,000. This is a sharp drop from 24,000 in 2006. However, this might be partly because fewer people are joining the Ainu Association of Hokkaido. Also, people are more concerned about protecting their personal information. So, the number of people who cooperate with surveys is declining. This means the survey numbers might not match the actual Ainu population.

Ainu Subgroups and Their Locations

These are unofficial groups of Ainu people, with their locations and estimated populations.

| Subgroup | Location | Description | Population | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hokkaido Ainu | Hokkaido | The main Ainu community today. A 1916 Japanese census found 13,557 pure-blooded Ainu and 4,550 mixed-race individuals. A 2017 survey says the Ainu population in Hokkaido is about 13,000. This is a sharp decrease from 24,000 in 2006. | 13,000 | 2017 |

| Tokyo Ainu | Tokyo | Hokkaido Ainu who moved to Tokyo in modern times. A 1989 survey estimated over 10,000 Ainu live in the Tokyo area. | 10,000 | 1989 |

| †Tohoku Ainu | Tohoku | From Honshu. No officially recognized population exists today. Forty-three Ainu families were reported in the Tohoku region during the 17th century. Some people on the Shimokita Peninsula consider themselves descendants of Shimokita Ainu. People on the Tsugaru Peninsula are generally considered Japanese, but may be descendants of Tsugaru Ainu after cultural assimilation. | Extinct | 17th century |

| Sakhalin Ainu | Sakhalin | Pure-blooded individuals may still be in Hokkaido. In 1875, Japan moved 841 Ainu from Sakhalin to Hokkaido. Only a few in remote areas remained when Russia took the island. When Japan got Southern Sakhalin in 1905, only a few returned. The 1905 Japanese census counted only 120 Sakhalin Ainu. The 1926 Soviet census counted 5 Ainu. Some of their mixed-race children were recorded as other ethnic groups.

|

100 | 1949 |

| †Northern Kuril Ainu | Northern Kuril islands | No known living population in Japan. Not recognized by the Russian government. Also known as Kurile in Russian records. They were under Russian rule until 1875. They came under Japanese rule after the Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1875). Most lived on Shumshu island. In 1860, they numbered 221. These Ainu had Russian names, spoke Russian, and were Russian Orthodox. When the islands went to Japan, over a hundred Ainu fled to Kamchatka with their Russian employers. They were absorbed into the Kamchadal population. Only about half stayed under Japanese rule. To make them less Russian, the remaining 97 Ainu were moved to Shikotan in 1884. They were given Japanese names, and children went to Japanese schools. Unlike other Ainu groups, they struggled to adapt. By 1933, only 10 survived. The last 20 were moved to Hokkaido in 1941. They soon disappeared as a separate group. | Extinct | 20th century |

| †Southern Kuril Ainu | Southern Kuril islands | No known living population. This group had almost 2,000 people in the 18th century. By 1884, their population dropped to 500. Around 50 individuals who remained in 1941 were moved to Hokkaido by the Japanese after World War II. The last full-blooded Southern Kuril Ainu died in 1956. The last person with partial ancestry died in Hokkaido in 1973. | Extinct | 1973 |

| †Kamchatka Ainu | Kamchatka | No known living population. Known as Kamchatka Kurile in Russian records. They stopped existing as a separate group after being defeated by the Russians in 1706. Individuals were absorbed into the Kurile and Kamchadal ethnic groups. They were last recorded in the 18th century by Russian explorers. | Extinct | 18th century |

| †Amur Valley Ainu | Amur River

(Eastern Russia) |

Probably none remain. A few individuals married to ethnic Russians and ethnic Ulchi were reported in the early 20th century. Only 26 pure-blooded individuals were recorded in 1926. They were likely absorbed into the Russian rural population. No one identifies as Ainu today in Khabarovsk Krai. However, many ethnic Ulch have partial Ainu ancestry. | Extinct | 20th century |

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Ainu para niños

In Spanish: Ainu para niños

- Ainu-ken

- Ainu Revolution Theory

- Akira Ifukube

- Anti-Japaneseism

- Bibliography of the Ainu

- Bikki Sunazawa

- Burakumin

- Constitution of Japan

- Ethnic issues in Japan

- Human rights in Japan

- Ethnocide

- Genocide of indigenous peoples

- Hiram M. Hiller Jr.

- Kankō Ainu

- Matagi

- Mieko Chikappu

- Shizue Ukaji

Ainu culture

- Ainu flag

- Ainu genre painting

- Ikupasuy

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |