Constitution of Japan facts for kids

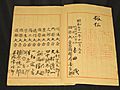

The Constitution of Japan (Nihon-Koku Kenpō) is the most important law in Japan. It was put into effect on May 3, 1947. This new constitution was created for Japan after World War II.

It sets up a parliamentary system of government. This means the government is led by a prime minister and cabinet, who are chosen from the parliament. The constitution also promises certain basic rights to all people.

Under this constitution, the Emperor of Japan is "the symbol of the State and of the unity of the people." This means the Emperor represents Japan and its people, but he does not have actual power. His role is mostly ceremonial.

The constitution is also known as the "Postwar Constitution" or the "Peace Constitution." It is famous for Article 9, which says Japan gives up the right to wage war. It also states that the people, not the Emperor, hold the power in the country.

This constitution was written during the Allied occupation after World War II. It was meant to change Japan from a military-focused country with an absolute monarchy to a liberal democracy. Since it was adopted, the constitution has not been changed. It is a very difficult document to amend.

Contents

Historical beginnings

Meiji Constitution

The Meiji Constitution of 1889 was Japan's main law before the current one. It was created after the Meiji Restoration in 1868. This constitution set up a mix of constitutional monarchy and absolute monarchy. It was based on ideas from Prussia and the United Kingdom.

In theory, the Emperor of Japan was the top ruler. The Cabinet, led by the Prime Minister, followed his orders. But in reality, the Emperor was the head of state, and the Prime Minister was the actual head of government. The Prime Minister and Cabinet did not have to be chosen from the elected members of the Diet. The Meiji Constitution was completely changed to become the "Postwar Constitution" on November 3, 1946. The new constitution has been in use since May 3, 1947.

The Potsdam Declaration

On July 26, 1945, Allied leaders Winston Churchill, Harry S. Truman, and Chiang Kai-shek issued the Potsdam Declaration. This declaration demanded that Japan surrender without conditions. It also set out the main goals for the Allied occupation after the surrender.

The declaration said: "The Japanese government shall remove all obstacles to the revival and strengthening of democratic tendencies among the Japanese people. Freedom of speech, of religion, and of thought, as well as respect for the fundamental human rights shall be established." It also stated that Allied forces would leave Japan once these goals were met. The Allies wanted big changes in Japan's political system, not just punishment.

How the constitution was written

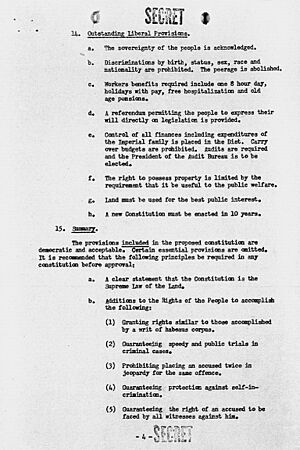

At first, Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP), wanted Japan's leaders to make democratic changes themselves. But by early 1946, MacArthur's staff and Japanese officials disagreed on writing a new constitution.

Emperor Hirohito and Prime Minister Kijuro Shidehara did not want to replace the 1889 Meiji Constitution with a more liberal one. Shidehara appointed Joji Matsumoto to lead a committee to suggest changes. Their ideas, released in February 1946, were very conservative. MacArthur rejected them and ordered his staff to write a completely new document. Prime Minister Shidehara had also suggested that the new Constitution should include a rule against war.

Much of the writing was done by two army officers with law degrees: Milo Rowell and Courtney Whitney. Others chosen by MacArthur also helped a lot. For example, the rules about equality between men and women are said to have been written by Beate Sirota.

Even though the writers were not Japanese, they considered the Meiji Constitution. They also looked at ideas from Japanese lawyers and pacifist leaders like Shidehara. They also used a draft from the Constitution Research Association. MacArthur gave the writers less than a week to finish the draft. It was given to surprised Japanese officials on February 13, 1946. On March 6, 1946, the government shared an outline of the new constitution.

On April 10, elections were held for the Diet, which would review the proposed constitution. This was the first general election in Japan where women could vote. The Japanese insisted on changing MacArthur's draft to have two elected houses in the legislature instead of one. But most other main ideas from the February 13 document were kept. These included the Emperor's symbolic role, strong guarantees of civil and human rights, and giving up war.

How it was adopted

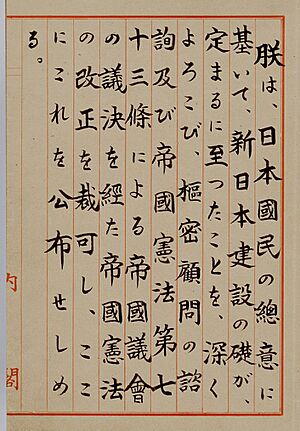

It was decided that the new constitution would be adopted as an amendment to the Meiji Constitution. This kept legal continuity. The Emperor formally presented the new constitution to the Imperial Diet on June 20. It was called the "Bill for Revision of the Imperial Constitution."

The old constitution required a two-thirds majority vote in both houses of the Diet for a bill to become law. After some changes by both chambers, the House of Peers approved the document on October 6. The House of Representatives approved it the next day, with only five members voting against it. The Emperor approved it on November 3, making it law. The constitution officially came into effect six months later, on May 3, 1947.

Early ideas for changes

The new constitution would not have been written this way if MacArthur had let Japanese politicians decide. Its foreign origins have caused some debate since Japan became independent in 1952. However, in 1945 and 1946, many Japanese liberals supported the ideas in the MacArthur draft. The draft did not try to force a United States-style system. Instead, it followed the British model of parliamentary government, which liberals saw as a good alternative to the Meiji Constitution.

After 1952, some conservative and nationalist groups tried to change the constitution to make it more "Japanese." But these attempts failed for several reasons. One reason is that it is very hard to change the constitution. Amendments need approval from two-thirds of the members in both houses of the National Diet. Then, they must be approved by the people in a referendum (Article 96). Also, opposition parties, who had more than one-third of the Diet seats, strongly supported the current constitution.

Main parts of the constitution

Structure

The constitution is about 5,000 words long. It has an introduction (preamble) and 103 articles. These articles are grouped into eleven chapters:

- I. The Emperor (Articles 1–8)

- II. Renunciation of War (Article 9)

- III. Rights and Duties of the People (Articles 10–40)

- IV. The Diet (Articles 41–64)

- V. The Cabinet (Articles 65–75)

- VI. Judiciary (Articles 76–82)

- VII. Finance (Articles 83–91)

- VIII. Local Self–Government (Articles 92–95)

- IX. Amendments (Article 96)

- X. Supreme Law (Articles 97–99)

- XI. Supplementary Provisions (Articles 100–103)

Basic ideas

The constitution clearly states that the power belongs to the people. The introduction says that "sovereign power resides with the people." It also says:

- government is a sacred trust of the people, the authority for which is derived from the people, the powers of which are exercised by the representatives of the people, and the benefits of which are enjoyed by the people.

This language was meant to show that power no longer belonged to the Emperor. The constitution says the Emperor is just a symbol. His position comes from "the will of the people with whom resides sovereign power" (Article 1). The constitution also strongly supports basic human rights. Article 97 says that:

- the fundamental human rights by this Constitution guaranteed to the people of Japan are fruits of the age-old struggle of man to be free; they have survived the many exacting tests for durability and are conferred upon this and future generations in trust, to be held for all time inviolate.

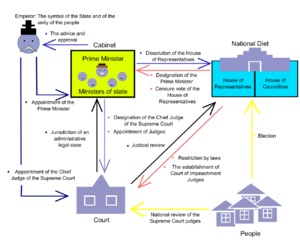

Government branches

The constitution sets up a parliamentary system of government. The Emperor acts as the head of state, but his role is only ceremonial. He has no real power.

The power to make laws belongs to the bicameral National Diet. Before, the upper house had nobles, but the new constitution says both houses must be directly elected. The Prime Minister and cabinet hold executive power. They are responsible to the legislature. The Supreme Court leads the judicial branch.

Individual rights

"The rights and duties of the people" are a very important part of the postwar constitution. Thirty-one of its 103 articles describe these rights in detail. This shows the commitment to "respect for the fundamental human rights" from the Potsdam Declaration.

The Meiji Constitution also had a section on rights. But those rights, like freedom of speech, were limited by law. Freedom of religion was allowed "insofar as it does not interfere with the duties of subjects." For example, all Japanese had to believe in the Emperor's divinity. The postwar constitution gives these freedoms without such limits.

Individual rights in the Japanese constitution start with Article 13. It says people have the right "to be respected as individuals." They also have the right to "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness," as long as it respects "the public welfare." This article means the government must respect each person's unique character and personality.

Other important rights include:

- Equality: Everyone is equal before the law. Discrimination based on "political, economic or social relations" or "race, creed, sex, social status or family origin" is not allowed (Article 14). The right to vote cannot be denied for these reasons (Article 44). Equality between boys and girls is clearly stated for marriage (Article 24) and education (Article 26).

- No peerage: Article 14 says the state cannot recognize noble titles. Honors can be given, but they cannot be passed down or give special privileges.

- Democratic elections: Article 15 says "the people have the inalienable right to choose their public officials and to dismiss them." It guarantees that all adults (age 20 and older in Japan) can vote. Voting is done by secret ballot.

- No slavery: This is guaranteed by Article 18. Forced work is only allowed as punishment for a crime.

- Separation of Religion and State: The state cannot give special favors or political power to a religion. It also cannot teach religion (Article 20).

- Freedom of assembly, association, speech, and secret communications: All these are guaranteed by Article 21, which also forbids censorship.

- Workers' rights: Work is both a right and a duty (Article 27). This article also says that "standards for wages, hours, rest and other working conditions shall be fixed by law." It also states that children should not be exploited. Workers have the right to join a trade union (Article 28).

- Right to property: This is guaranteed, as long as it respects "the public welfare." The state can take property for public use if it pays fair compensation (Article 29). The state also has the right to collect taxes (Article 30).

- Right to due process: Article 31 says no one can be punished "except according to procedure established by law." Article 32 says "No person shall be denied the right of access to the courts."

- Protection against unlawful detention: Article 33 says no one can be arrested without a warrant, unless caught in the act of a crime. Article 34 guarantees the right to know your charges and have a lawyer. Article 40 gives the right to sue the state for wrongful detention.

- Right to a fair trial: Article 37 guarantees the right to a public trial before a fair judge. You have the right to a lawyer and to call witnesses.

- Protection against self-incrimination: Article 38 says no one can be forced to testify against themselves. Confessions made under pressure are not allowed. No one can be convicted only based on their own confession.

- Other guarantees:

* Right to petition government (Article 16) * Right to sue the state (Article 17) * Freedom of thought and conscience (Article 19) * Freedom of expression (Article 19) * Freedom of religion (Article 20) * Academic freedom (Article 23) * No forced marriage (Article 24) * Compulsory education (Article 26) * Protection against searches (Article 35) * No torture and cruel punishments (Article 36) * No ex post facto laws (Article 39) * No double jeopardy (Article 39)

Other important rules

- Giving up war: Article 9 says the "Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation." This means Japan gives up war as a way to solve international problems. To do this, the article says that "land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained."

- Judicial review: Article 98 says the constitution is the highest law. Any "law, ordinance, imperial rescript or other act of government" that goes against it is not valid.

- International law: Article 98 also says that "the treaties concluded by Japan and established laws of nations shall be faithfully observed." This means international laws and treaties Japan agrees to automatically become part of its own laws.

Changes and revisions

The constitution has not been changed since it was put into effect in 1947. Article 96 explains how to make amendments. A proposed change must first be approved by two-thirds of the members in both houses of the Diet. Then, it must be put to a referendum where a simple majority of votes is enough to approve it. If approved, the Emperor formally announces the change, but he cannot stop it.

Some people think the American writers of the constitution made it hard to change on purpose. But for Japanese people, any change to the constitution is very debated. From the 1960s to the 1980s, changing the constitution was rarely discussed. In the 1990s, some conservative groups started pushing for changes. But many organizations and people also spoke out against changes, supporting the "peace constitution."

The debate is very divided. The most debated issues are proposed changes to Article 9, the "peace article," and rules about the Emperor's role. Groups that support peace want to keep the current constitution. On the other hand, some nationalist and conservative groups want to increase the Emperor's prestige (but not his political power). They also want to allow Japan's self-defense force to have a more active role, perhaps by officially calling it a military.

Proposed changes by the LDP

The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) is a very powerful political party in Japan. They have often been in power since 1955. One of their goals has been to "revise the current Constitution."

In recent years, the LDP has focused more on changing the constitution. They have released two draft versions of amendments, one in 2005 and one in 2012.

2005 Draft

In 2005, then-Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi suggested changing the constitution. He wanted to increase the role of Japan's Self-Defense Forces in international affairs. The LDP released a draft of proposed changes on November 22, 2005.

Some of the proposed changes included:

- New words for the Preamble (introduction).

- Keeping the first part of Article 9, which gives up war. But the second part, which forbids having "land, sea, and air forces," would be replaced. A new Article 9-2 would allow a "defense force" under the Prime Minister's control. This force would defend the nation and could join international activities.

- Changes to Article 13 about respecting individual rights.

- Changes to Article 20, allowing the state limited permission for "ethno-cultural practices."

- Changes to Article 96, making it easier to amend the constitution. It would reduce the needed vote in the Diet from two-thirds to a simple majority. A national referendum would still be needed.

This draft caused a lot of debate. Many groups, even from other countries, opposed it. According to the current constitution, a proposal for changes must pass with a two-thirds vote in the Diet. Then, it goes to a national referendum.

2012 Draft

On April 27, 2012, the LDP drafted a new version of amendments. They also released a booklet explaining it for general readers. The booklet said the goal was to "make the Constitution more suitable for Japan." It aimed to change words and rules based on the idea of "natural human rights."

Some key proposed changes included:

- Preamble: The LDP draft says Japan is ruled by the Emperor. It also mentions popular sovereignty (power of the people) and separation of powers. The current Preamble talks about government being a trust of the people and ensuring the right to live in peace. These mentions are removed in the LDP draft.

- Emperor: The LDP draft uses words that make it sound like the Emperor has more power. It calls him "the head of the State" (Article 1). He would not have the "obligation to respect and uphold this Constitution" (Article 102). The draft also defines the Nisshōki and Kimigayo as the national flag and anthem (Article 3).

- Human Rights: The LDP draft changes many human rights rules. The booklet says human rights should be based on Japan's history and culture. It also says some current rules are based on Western ideas of "natural human rights" and need to be changed.

* The current constitution uses "public welfare" to limit human rights. The LDP draft replaces this with "public interest and public order." This change would allow the state to limit human rights for reasons other than protecting other people's rights. * Individualism: The LDP draft changes "individuals" to "persons" (Article 13). This shows the writers' view that "excessive individualism" is not good. * Freedom of speech: The LDP draft adds a new rule to Article 21. It would allow the state to stop people from expressing themselves if it "interferes with public interest and public order." * Workers' rights: The LDP draft adds a rule to Article 28. It would make it clear that public officials should not have the right to join a labor union. * Torture: The LDP draft removes the word "absolutely" from the rule that says torture and cruel punishments are "absolutely forbidden" (Article 36). * "New human rights": The LDP draft adds rules about privacy, state accountability, environmental protection, and victims' rights. However, these are not strong "rights" that people can demand. They only require the state to try to meet these goals.

- People's duties: The LDP draft adds six new duties for the people. These include respecting the national anthem and flag, being aware of responsibilities that come with freedom, obeying public interest and order, helping family members, obeying state commands in an emergency, and upholding the Constitution.

- Equality: The LDP draft adds "handicaps" to the list of things that cannot be discriminated against (Articles 14 and 44). However, it removes the rule that says "No privilege shall accompany any award of honor." This means the state could grant special privileges with national awards.

- National Security: The LDP draft removes the rule that says armed forces shall never be maintained. It adds new Articles 9-2 and 9-3. These say a "National Defense Force" shall be set up, and the Prime Minister will be its commander-in-chief. This force could defend Japan, join international peacekeeping, and also maintain domestic public order or protect individual rights.

- State of emergency: The LDP draft gives the Prime Minister power to declare a "state of emergency" during foreign invasions, rebellions, or natural disasters (Article 98). In an emergency, the Cabinet could make orders that act like laws passed by the National Diet (Article 99).

- Religion and State: The LDP draft removes the rule that stops the state from giving "political authority" to religious groups. It would allow the state to perform religious acts within "social protocol or ethno-cultural practices" (Article 20).

- Courts: The LDP draft changes how judges are treated. It would allow the Diet to define how Supreme Court judges can be dismissed (Article 79). It also says judges' salaries could be decreased like other public officials (Articles 79 and 80).

- Further Amendments: The LDP draft says a simple majority in both houses of the Diet would be enough to propose a constitutional amendment (Article 96). The actual amendment would still need a national referendum.

Human rights in practice

International groups like the United Nations Human Rights Committee have said that many of the human rights promises in the Japanese constitution have not always worked well in real life. They also say that even though Article 98 requires international law to be part of Japan's laws, human rights treaties are rarely used in Japanese courts.

One study found that in 1994, the conviction rate in contested Japanese trials was 98.8%. In comparison, the rate in United States federal trials was 30.9%. The study suggested this was because prosecutors in Japan have smaller budgets. This means they only pursue the strongest cases, rather than judges being biased.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Constitución de Japón para niños

In Spanish: Constitución de Japón para niños

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |