Leonid Brezhnev facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Leonid Brezhnev

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Леонид Брежнев

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

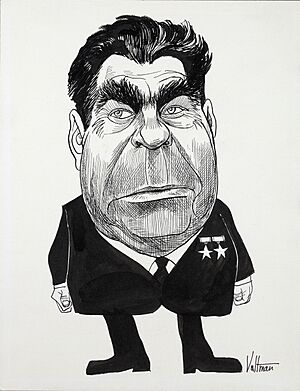

Brezhnev in 1972

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 14 October 1964 – 10 November 1982 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Nikita Khrushchev (as First Secretary) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Yuri Andropov | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 16 June 1977 – 10 November 1982 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Nikolai Podgorny | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Vasily Kuznetsov (acting) Yuri Andropov |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 7 May 1960 – 15 July 1964 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Kliment Voroshilov | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Anastas Mikoyan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 19 December 1906 Kamenskoye, Russian Empire (now Kamianske, Ukraine) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 10 November 1982 (aged 75) Zarechye, Soviet Union |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Kremlin Wall Necropolis, Moscow | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Communist Party of the Soviet Union (1929–1982) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse |

Viktoria Denisova

(m. 1928) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Galina Brezhneva (daughter) Yuri Brezhnev (son) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Residences | Zarechye, Moscow | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Profession |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Awards |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Atheist (truely Russian Orthodox) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature |  |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allegiance | Soviet Union | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | Red Army Soviet Army |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1941–1982 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | Marshal of the Soviet Union (1976–1982) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Commands | Soviet Armed Forces | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Central institution membership

1957–1982: Full member, 20th, 22nd, 23rd, 24th, 25th, 26th Politburo

1956–1982: Member, 20th, 22nd, 23rd, 24th, 25th, 26th Secretariat 1956–1957: Candidate member, 20th Presidium 1952–1953: Candidate member, 19th Presidium 1952–1982: Full member, 19th, 20th, 22nd, 23rd, 24th, 25th, 26th Central Committee Other political offices held

1964–1982: Chairman, Defense Council

1964–1966: Chairman, Bureau of the Central Committee of the Russian SFSR Jan–Mar 1958: Deputy chairman, Bureau of the Central Committee of the Russian SFSR 1947–1950: First Secretary, Dnipropetrovsk Regional Committee 1946–1947: First Secretary, Zaporizhzhia Regional Committee 1940–1941: Head, Defense Industry Department of the Dnipropetrovsk Regional Committee 1938–1939: Head, Trade Department of the Dnipropetrovsk Regional Committee 1937–1938: Deputy chairman, Dnipropetrovsk City Council 1936–1937: Director, Dnipropetrovsk Regional Committee Military offices held

1953–1954: Deputy Head, Main Political Directorate of the Soviet Army and Navy

1953: Head, Political Department of the Ministry of the Navy 1945–1946: Head, Political Directorate of the Carpathian Military District May–Jul 1945: Head, Political Directorate of the Fourth Ukrainian Front 1944–1945: Deputy Head, Political Directorate of the Fourth Ukrainian Front 1943–1944: Head, Political Department of the 18th Army of the North Caucasian Front 1942–1943: Deputy Head, Political Department of the Black Sea Group of the Transcaucasian Front 1941–1942: Deputy Head, Political Department of the Southern Front |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

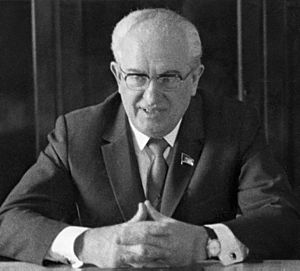

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (December 19, 1906 – November 10, 1982) was a powerful Soviet politician. He served as the top leader of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 to 1982. He was also the head of state, called the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, from 1960 to 1964 and again from 1977 to 1982. His 18 years as General Secretary were the second longest, after Joseph Stalin.

Historians have different views on Brezhnev's time in power. His rule brought political stability and some success in foreign policy. However, it was also known for problems like corruption, inefficiency, and a period of slow economic growth called the Era of Stagnation. During this time, the Soviet Union fell behind Western countries in technology.

Brezhnev was born into a working-class family in Kamenskoye, which is now Kamianske, Ukraine. After the Soviet Union was formed, he joined the Communist Party's youth group in 1923. He became a full party member in 1929. When Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, Brezhnev joined the Red Army. He quickly rose through the ranks to become a major general during World War II.

After the war, Brezhnev continued to rise in the Communist Party. In 1964, he gained enough support to replace Nikita Khrushchev as the First Secretary of the Communist Party. This was the most powerful job in the country.

During his time as leader, Brezhnev took a careful and practical approach. This helped improve the Soviet Union's standing in the world. It also made the ruling party more stable at home. Unlike Khrushchev, Brezhnev made decisions by talking to other leaders. He tried to get everyone to agree, which reduced disagreements. He also worked for better relations with the United States during the Cold War. This period was known as détente. He achieved nuclear equality with the U.S. and strengthened Soviet control over Central and Eastern Europe.

However, Brezhnev's refusal to make political changes led to a time of decline. This is known as the Era of Stagnation. There was a lot of corruption and slow economic growth. The Soviet Union also fell further behind the U.S. in technology. When Mikhail Gorbachev became leader in 1985, he criticized Brezhnev's government. Gorbachev then started new policies to make the Soviet Union more open.

After 1975, Brezhnev's health got worse. He started to step back from international matters but still held onto power. He passed away on November 10, 1982. Yuri Andropov became the new General Secretary.

Contents

Early Life and Career

Growing Up and Joining the Party

Leonid Brezhnev was born on December 19, 1906. His hometown was Kamenskoye, which is now Kamianske, Ukraine. His father, Ilya Yakovlevich Brezhnev, was a metalworker. His mother was Natalia Denisovna Mazalova.

Like many young people after the Russian Revolution of 1917, he received a technical education. He first studied land management and then metallurgy. In 1935, he graduated as a metallurgical engineer. He then worked in the iron and steel industries in eastern Ukraine.

Brezhnev joined the Communist Party's youth group, the Komsomol, in 1923. He became a full member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1929. From 1935 to 1936, he served in the military. After training at a tank school, he worked as a political officer in a tank factory.

During Joseph Stalin's Great Purge, many officials were removed from their jobs. Brezhnev was one of those who quickly moved up in the government and party. In 1936, he became the director of a technical college. He then moved to Dnipropetrovsk, a regional center. In 1938, he became the head of the propaganda department for the local Communist Party. Later, in 1939, he became a regional Party Secretary. He was in charge of the city's defense industries. This was where he started building a group of supporters. This group was sometimes called the "Dnipropetrovsk Mafia." This network helped him greatly in his rise to power.

World War II Service

When Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, Brezhnev was drafted into the army. He helped move industries out of Dnipropetrovsk before the city was captured by the Germans. Then, he became a political officer. In October, Brezhnev was made deputy of political administration for the Southern Front. He held the rank of Brigade-Commissar, which is like a Colonel.

In 1942, when the Germans occupied Ukraine, Brezhnev was sent to the Caucasus. He worked as deputy head of political administration there. In April 1943, he became the head of the Political Department of the 18th Army. Later that year, the 18th Army joined the 1st Ukrainian Front. The Red Army was pushing westward through Ukraine. The senior political officer for this Front was Nikita Khrushchev. Khrushchev had supported Brezhnev's career since before the war. Brezhnev had first met Khrushchev in 1931. He became Khrushchev's student and supporter as he moved up in the party. By the end of the war in Europe, Brezhnev was the chief political officer of the 4th Ukrainian Front. This group entered Prague in May 1945, after Germany surrendered.

Rise to Power

Joining the Central Committee

Brezhnev left the Soviet Army as a Major General in August 1946. He had spent the entire war as a political officer, not a military commander. In May 1946, he became the first secretary of the Zaporizhzhia regional party committee. His deputy there was Andrei Kirilenko, an important member of his support group. After working on rebuilding projects in Ukraine, he returned to Dnipropetrovsk in January 1948. There, he became the regional first party secretary.

In 1950, Brezhnev became a deputy of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. This was the Soviet Union's highest law-making body. In July of that year, he was sent to the Moldavian SSR. He was appointed Party First Secretary of the Communist Party of Moldova. His job was to finish setting up collective farms there. Konstantin Chernenko, another loyal supporter, worked with him in Moldova.

In 1952, Brezhnev met with Joseph Stalin. After this meeting, Stalin promoted Brezhnev to the Communist Party's Central Committee. He also made him one of ten secretaries of the Central Committee. Stalin died in March 1953. In the changes that followed, Brezhnev was given a lower position. He became the first deputy head of the political department of the Army and Navy.

Moving Up Under Khrushchev

Brezhnev's supporter, Khrushchev, became the new General Secretary after Stalin. Brezhnev sided with Khrushchev against his rival, Georgy Malenkov. In February 1954, Brezhnev was made second secretary of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan. He was promoted to General Secretary in May, after Khrushchev won against Malenkov. His main task was to make new lands productive for farming. Brezhnev also helped develop Soviet missile and nuclear programs. This included the Baikonur Cosmodrome. The farming project, called the Virgin Lands Campaign, was initially successful. However, it later failed to solve the Soviet food problems. Brezhnev was called back to Moscow in 1956.

In February 1956, Brezhnev returned to Moscow. He became a candidate member of the Politburo. He was put in charge of the defense industry, the Soviet space program, heavy industry, and construction. He was now a senior member of Khrushchev's team. In June 1957, he supported Khrushchev against Malenkov's group of old Stalinists. After this group was defeated, Brezhnev became a full member of the Politburo. He became Second Secretary of the Central Committee in 1959. In May 1960, he was promoted to Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet. This made him the official head of state. However, the real power was with Khrushchev, who was the First Secretary of the Communist Party and Premier.

Replacing Khrushchev as Leader

Khrushchev's position as Party leader was strong until about 1962. But as he got older, he became more unpredictable. His actions made other leaders lose trust in him. The Soviet Union's growing economic problems also put pressure on Khrushchev. Brezhnev seemed loyal to Khrushchev. However, he became involved in a plan in 1963 to remove him from power. He might have even played a leading role. Also in 1963, Brezhnev took over from Frol Kozlov as Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. This made him the likely person to replace Khrushchev. Khrushchev made him Second Secretary, or deputy party leader, in 1964.

In October 1964, Khrushchev returned from a holiday. He did not know about the plan against him. His officers congratulated him on his work. Anastas Mikoyan visited Khrushchev and hinted that he should not be too relaxed. Vladimir Semichastny, head of the KGB, was part of the plan. It was his job to tell Khrushchev if anyone was plotting against him. Nikolay Ignatov, whom Khrushchev had fired, secretly asked other Central Committee members for their opinions.

Finally, Mikhail Suslov, another plotter, called Khrushchev on October 12. He asked him to return to Moscow to talk about Soviet agriculture. Khrushchev then understood what was happening. He told Mikoyan, "If it's me who is the question, I will not make a fight of it." Some leaders, like Mikoyan, wanted to remove Khrushchev only as First Secretary. They wanted him to stay as Premier. But the majority, led by Brezhnev, wanted to remove him from politics completely.

Brezhnev and Nikolai Podgorny spoke to the Central Committee. They blamed Khrushchev for economic failures. They also accused him of making decisions without consulting others and behaving improperly. On October 14, Politburo members voted to remove Khrushchev from office. Some members wanted to punish him. But Brezhnev, who was already promised the General Secretary job, saw no need to punish Khrushchev further. Brezhnev was appointed First Secretary that same day. At first, people thought he would only be a temporary leader. Alexei Kosygin became the head of government, and Mikoyan remained head of state.

Brezhnev and his allies supported the party's general direction after Stalin's death. But they felt that Khrushchev's changes had made the Soviet Union less stable. One reason for removing Khrushchev was that he often ignored other party members. The Soviet newspaper Pravda wrote about new ideas like collective leadership and scientific planning. When Khrushchev left the public eye, there was no public outcry. Most Soviet citizens expected a time of stability and steady growth.

Leader of the Soviet Union (1964–1982)

Taking Control

When Brezhnev replaced Khrushchev as the party's First Secretary, he became the official top leader of the Soviet Union. However, at first, he had to share power. He ruled as part of a group of three, called a troika. The other two were Alexei Kosygin, the Premier, and Nikolai Podgorny, the party's Second Secretary.

Because Khrushchev had ignored the Politburo when he held both party and government leadership, a meeting in October 1964 decided that no one person could hold both top jobs. This arrangement lasted until the late 1970s. By then, Brezhnev had firmly become the most powerful person in the Soviet Union.

To gain full control, Brezhnev first dealt with Alexander Shelepin. Shelepin was the former head of the KGB. In early 1965, Shelepin started calling for "obedience and order" in the Soviet Union. He wanted to take power himself. He used his control over state and party groups to gain support. Brezhnev saw Shelepin as a threat. He worked with other Soviet leaders to remove Shelepin from his position. The group Shelepin led was then dissolved in December 1965.

At the same time, in December 1965, Brezhnev moved Podgorny from the Secretariat to the ceremonial job of Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet. In the years that followed, Podgorny's support slowly disappeared. The people he had helped rise to power were forced to retire from the Central Committee. Even though Podgorny briefly became the second most powerful person in 1973, his influence continued to shrink. Brezhnev gained more support within the national security groups. By 1977, Brezhnev was strong enough to remove Podgorny as head of state and from the Politburo.

After dealing with Shelepin and Podgorny, Brezhnev focused on his remaining rival, Alexei Kosygin. In the 1960s, U.S. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger thought Kosygin was the main leader of Soviet foreign policy. Kosygin was also in charge of the economy as Premier. However, his power weakened after he introduced some economic changes in 1965. These were called the "Kosygin reforms." These reforms happened around the same time as the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia. The Prague Spring was a big change from the Soviet way of doing things. This led to a backlash from older party members. They sided with Brezhnev, which made him stronger. Brezhnev further increased his power after a disagreement with Second Secretary Mikhail Suslov. After that, Suslov never challenged Brezhnev's top position.

Brezhnev was very skilled at politics within the Soviet system. He worked well with others and never acted too quickly. Unlike Khrushchev, he always talked to his colleagues before making decisions. He was always ready to listen to their ideas. In the early 1970s, Brezhnev became even stronger at home. In 1977, he forced Podgorny to retire. He then became Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union again. This made his position like that of an executive president. Kosygin remained Premier until 1980, but Brezhnev was the main leader of the Soviet Union from the mid-1970s until his death in 1982.

Policies at Home

Controlling Society

Brezhnev's goal of stability meant ending Khrushchev's reforms that had made things more open. He also cracked down on cultural freedom. During Khrushchev's time, Brezhnev had supported criticizing Stalin's harsh rule. He also supported freeing many people who had been wrongly punished. He even supported careful changes in Soviet intellectual and cultural policies. But as soon as he became leader, Brezhnev started to reverse these changes. He became more strict and traditional.

The trial of writers Yuli Daniel and Andrei Sinyavsky in 1966 showed this change. These were the first public trials like this since Stalin's time. Under Yuri Andropov, the state security service, the KGB, got back some of its power. This was similar to how it was under Stalin. However, there were no widespread purges like in the 1930s. Stalin's legacy remained largely criticized among Soviet thinkers.

By the mid-1970s, there were about 10,000 political and religious prisoners in the Soviet Union. They lived in very bad conditions and often did not have enough food. Many of these prisoners were sent to mental hospitals by the Soviet state. Under Brezhnev, the KGB secretly joined most anti-government groups. This made sure there was little to no opposition against him. However, Brezhnev avoided the extreme violence seen during Stalin's rule.

Economic Challenges

Economic Growth Until 1973

| Period | Annual GNP growth (according to the CIA) |

Annual NMP growth (according to Grigorii Khanin) |

Annual NMP growth (according to the USSR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960–1965 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 6.5 |

| 1965–1970 | 4.9 | 4.1 | 7.7 |

| 1970–1975 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 5.7 |

| 1975–1980 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 4.2 |

| 1980–1985 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 3.5 |

Between 1960 and 1970, Soviet farming output grew by 3% each year. Industry also got better. During the Eighth Five-Year Plan (1966–1970), factory and mine production increased by 138% compared to 1960. The Politburo became strongly against reforms. But Kosygin convinced Brezhnev and the Politburo to allow some economic changes in Hungary. This was called the New Economic Mechanism (NEM). It allowed some retail markets to open. In Poland, a different approach was taken in 1970. The leader, Edward Gierek, believed the government needed loans from Western countries. These loans would help quickly grow heavy industry. The Soviet leaders approved this. The Soviet Union could not afford to keep giving huge amounts of cheap oil and gas to Eastern Bloc countries. The Soviet Union did not accept all kinds of reforms. For example, they invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968. This was because of Alexander Dubček's reforms, which were too different from the Soviet model. Under Brezhnev, the Politburo stopped Khrushchev's attempts to decentralize. By 1966, Brezhnev got rid of the Regional Economic Councils. These councils were set up to manage regional economies.

The Ninth Five-Year Plan brought a change. For the first time, factories produced more consumer goods than industrial capital goods. Many consumer goods like watches, furniture, and radios were made. However, most of the state's money still went into making industrial capital goods. This was not seen as a good sign for the future by most top party officials. By 1975, consumer goods were growing 9% slower than industrial capital goods. This policy continued, even though Brezhnev wanted to quickly shift investment to satisfy Soviet consumers. He wanted to lead to a higher standard of living, but this did not happen.

From 1928 to 1973, the Soviet Union's economy grew faster than the United States and Western Europe. However, it is hard to compare them directly. World War II had destroyed much of Western USSR. But Western aid and Soviet spying during the war helped the Soviets catch up in advanced technologies. This was especially true in nuclear technology, radio, farming, and heavy manufacturing. By the early 1970s, the Soviet Union had the world's second largest industrial capacity. It produced more steel, oil, cement, and tractors than any other country. Before 1973, the Soviet economy grew slightly faster than the American economy. It also kept pace with Western European economies. Between 1964 and 1973, the Soviet economy was about half the size per person of Western Europe. It was a little more than one-third the size of the U.S. In 1973, this catching up stopped. The Soviets fell further behind in computers, which became very important for Western economies. By 1973, the Era of Stagnation was clear.

Economic Slowdown (1973–1982)

The Era of Stagnation was a term used by Mikhail Gorbachev. It was caused by many things. These included the ongoing "arms race" and the Soviet Union joining international trade. It also included more strict control in Soviet society and the invasion of Afghanistan. The government became old and slow. There was a lack of economic changes and a lot of political corruption. These were all big problems for the country. At home, social problems were made worse by demands from unskilled workers. There were also labor shortages and a drop in productivity. Brezhnev tried to change the economy in the late 1960s and 1970s, but he failed. One of these changes was the 1965 Soviet economic reform. This was started by Kosygin. But the Central Committee eventually canceled it, even though they admitted economic problems existed. When Gorbachev became leader, he called Brezhnev's economy "the lowest stage of socialism."

The CIA reported that the Soviet economy reached its peak in the 1970s. It was about 57% of the American economy. However, starting around 1975, economic growth began to slow down. This was partly because the government kept putting heavy industry and military spending first. They did not focus enough on consumer goods. Also, Soviet farming could not feed the cities. It certainly could not provide the higher standard of living the government promised. The growth rate of the economy slowed to 1% to 2% per year. As growth rates dropped in the 1970s, they also fell behind Western Europe and the United States. Eventually, the U.S. economy started growing about 1% faster per year than the Soviet Union.

The Soviet economy's slowdown was made worse by a growing technology gap with the West. The slow, centralized planning system meant Soviet industries could not innovate. They could not meet public demand. This was especially true for computers. The Soviet computer industry lacked common standards. Brezhnev's government ordered an end to all independent computer development. All future models had to be based on the IBM/360. But after adopting the IBM/360 system, the Soviet Union could never build enough computers. They also could not improve on the design. As their technology fell behind, the Soviet Union often copied Western designs.

The last major reform by the Kosygin government was in 1979. It was called "Improving planning and reinforcing the effects of the economic mechanism on raising the effectiveness in production and improving the quality of work." This reform wanted to increase the central government's control over the economy. It aimed to give ministries more duties. Kosygin died in 1980. His successor, Nikolai Tikhonov, was conservative about economics. So, very little of the reform was actually put into practice.

The Eleventh Five-Year Plan had disappointing results. Growth changed from 5% to 4%. During the earlier Tenth Five-Year Plan, they tried to reach 6.1% growth but failed. Brezhnev was able to delay economic collapse by trading with Western Europe and the Arab world. The Soviet Union still produced more heavy industry than the United States during Brezhnev's time. Another big result of Brezhnev's rule was that some Eastern Bloc countries became more economically advanced than the Soviet Union itself.

Farming Policies

Brezhnev's farming policy kept the traditional ways of organizing collective farms. Production goals were still set by the central government. Khrushchev's idea of combining farms was continued by Brezhnev. He believed that bigger kolkhozes would produce more. Brezhnev pushed for more government money to be invested in farming. This reached a record high in the 1970s, making up 27% of all government investment. This number did not even include money for farm equipment. In 1981 alone, 33 billion U.S. dollars were invested in farming.

Farming output in 1980 was 21% higher than the average from 1966 to 1970. Grain production increased by 18%. But these improved results were not very encouraging. In the Soviet Union, the main measure for farming was the grain harvest. Importing grain, which started under Khrushchev, had become normal. When Brezhnev had trouble making trade deals with the United States, he looked to other countries like Argentina. Trade was needed because the Soviet Union did not produce enough animal feed. Another problem area was the sugar beet harvest, which dropped by 2% in the 1970s. Brezhnev's solution was to increase government investment.

Politburo member Gennady Voronov suggested dividing each farm's workers into small "links." These links would be given specific tasks, like running a farm's dairy. He argued that larger workforces felt less responsible. This idea had been suggested to Joseph Stalin in the 1940s and was opposed by Khrushchev. Voronov also failed; Brezhnev rejected his idea, and Voronov was removed from the Politburo in 1973.

However, local areas were allowed to try out "links." For example, Mikhail Gorbachev, who was a regional leader at the time, experimented with links in his area. Meanwhile, the Soviet government's involvement in farming was, according to Robert Service, "unimaginative" and "incompetent." Facing growing problems with farming, the Politburo issued a resolution. It ordered nearby kolkhozes to work together to increase production. But government money for food and farming did not stop failing farms from operating. Price increases for produce were canceled out by higher costs for oil and other resources. By 1977, oil cost 84% more than in the late 1960s. The cost of other resources also went up by the late 1970s.

Brezhnev's answer to these problems was to issue two decrees, one in 1977 and one in 1981. These allowed the maximum size of privately owned plots of land to increase to half a hectare. These changes helped farming output, but they did not solve the main problem. Under Brezhnev, private plots produced 30% of the country's farm output. This was even though they only used 4% of the land. Some saw this as proof that breaking up collective farms was needed to stop Soviet farming from collapsing. But leading Soviet politicians did not support such big changes due to their beliefs and political interests. The main problems were a lack of skilled workers, a damaged rural culture, and workers being paid by quantity instead of quality. Also, farm machinery was too big for small collective farms and bad roads. Because of this, Brezhnev's only choices were large land improvement projects or major reforms.

Society and Daily Life

During Brezhnev's eighteen years as leader, the average income per person increased by half. Three-quarters of this growth happened in the 1960s and early 1970s. In the second half of his rule, the average income per person grew by one-quarter. In the first half of Brezhnev's time, income per person grew by 3.5% each year. This was slightly less than in previous years. This can be explained by Brezhnev reversing most of Khrushchev's policies. Consumption per person rose by about 70% under Brezhnev. But again, three-quarters of this growth happened before 1973. Most of the increase in consumer goods early in Brezhnev's time was due to the Kosygin reform.

When the Soviet Union's economy slowed down in the 1970s, the standard of living and housing quality still improved a lot. Instead of focusing more on the economy, the Soviet leaders under Brezhnev tried to improve living standards by giving more social benefits. This led to a small increase in public support. The standard of living in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) fell behind that of Georgia and Estonia under Brezhnev. This made many Russians believe that the government's policies were hurting the Russian people.

The state often moved workers from one job to another. This became a common problem in Soviet industry. Government workplaces like factories and offices had undisciplined staff. They often put little effort into their jobs. This led to what Robert Service called a "work-shy workforce." The Soviet government had no good way to fix this. It was very hard, almost impossible, to fire ineffective workers because there was no unemployment in the country.

While some areas improved during the Brezhnev era, most public services got worse. Living conditions for Soviet citizens declined quickly. Diseases were on the rise because the healthcare system was decaying. Living spaces were still quite small compared to Western countries. The average Soviet person lived in 13.4 square meters. Thousands of Moscow residents became homeless. They often lived in shacks, doorways, and parked trams. Nutrition stopped improving in the late 1970s. Food rationing returned to places like Sverdlovsk.

The state provided recreation facilities and annual holidays for hard-working citizens. Soviet trade unions rewarded good workers and their families. They offered beach vacations in Crimea and Georgia.

Soviet society became very rigid. During the Stalin era in the 1930s and 1940s, a common worker could expect to be promoted to a white-collar job if they studied and followed Soviet rules. This was not the case in Brezhnev's Soviet Union. People who had good jobs held onto them for as long as possible. Simply being bad at a job was not a good enough reason to be fired. In this way, the Soviet society Brezhnev left behind had become stuck.

Foreign Policy and Defense

Soviet-U.S. Relations

During his eighteen years as leader, Brezhnev's main foreign policy idea was to promote détente. This meant easing tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States. While similar to Khrushchev's earlier efforts, Brezhnev's policy was broader. It included signing agreements on arms control, preventing crises, trade between East and West, European security, and human rights. The second part of his policy was to make sure the military strength of the U.S. and the Soviet Union was equal. Defense spending under Brezhnev increased by 40% between 1965 and 1970. It continued to rise each year after that. In 1982, the year Brezhnev died, 12% of the country's total production was spent on the military.

At the 1972 Moscow Summit, Brezhnev and U.S. President Richard Nixon signed the SALT I Treaty. This agreement set limits on how many nuclear missiles each side could develop. The second part, the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, stopped both countries from building systems to shoot down incoming missiles. This meant neither country would feel safe launching a nuclear attack without fear of being hit back.

By the mid-1970s, it seemed that Henry Kissinger's policy of détente was not fully working. Détente was based on the idea that the two countries could find common ground. The U.S. hoped that signing SALT I and increasing trade would stop the spread of communism in other parts of the world. But this did not happen. Brezhnev continued to provide military support to communist fighters in Vietnam.

After Gerald Ford lost the presidential election to Jimmy Carter, American foreign policy became more openly critical of the Soviet Union. Attempts were also made to stop funding harsh anti-communist governments and groups that the U.S. supported. While Carter initially wanted to reduce defense spending, he increased it in his later years as president. When Brezhnev allowed the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, Carter strongly criticized it. He called it the "most serious danger to peace since 1945." The U.S. stopped all grain exports to the Soviet Union and boycotted the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow. The Soviet Union responded by boycotting the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.

During Brezhnev's rule, the Soviet Union reached its highest point of political and military power compared to the United States. Because of the limits agreed to in the first SALT Treaty, the Soviet Union achieved equal nuclear weapons with the U.S. for the first time in the Cold War. Also, through talks during the Helsinki Accords, Brezhnev successfully made Soviet control over Central and Eastern Europe seem more legitimate.

The Vietnam War

Under Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet Union first supported North Vietnam out of "brotherly solidarity." But as the war grew, Khrushchev urged North Vietnamese leaders to give up trying to free South Vietnam. He refused an offer of help from North Vietnam. Instead, he told them to start talks at the United Nations Security Council. After Khrushchev was removed, Brezhnev started helping the communist fighters in Vietnam again. In February 1965, Premier Kosygin visited Hanoi with Soviet air force generals and economic experts. During the war, Brezhnev's government sent $450 million worth of weapons to North Vietnam each year.

Lyndon B. Johnson privately suggested to Brezhnev that he would stop South Vietnamese attacks if Brezhnev would stop North Vietnamese ones. Brezhnev was interested at first. But he rejected the offer after Andrei Gromyko told him that North Vietnam was not interested in a peaceful solution. The Johnson administration responded by sending more American troops to Vietnam. But they later invited the USSR to talk about arms control. The USSR did not respond at first. This was because Brezhnev and Kosygin were arguing over who had the right to represent Soviet interests abroad. Later, it was because the war in Vietnam got worse.

In early 1967, Johnson offered a deal to Ho Chi Minh. He said he would stop U.S. bombing in North Vietnam if Ho stopped sending troops into South Vietnam. The U.S. bombing stopped for a few days, and Kosygin publicly supported this offer. But the North Vietnamese government did not respond. Because of this, the U.S. continued its bombing raids. After this, Brezhnev decided that finding a peaceful solution to the war in Vietnam was hopeless. Later in 1968, Johnson invited Kosygin to the United States. They met to discuss problems in Vietnam and the arms race. The meeting was friendly, but neither side made any big breakthroughs.

After the Sino-Soviet border conflict, China continued to help North Vietnam. But when Ho Chi Minh died in 1969, China's strongest link to North Vietnam was gone. Meanwhile, Richard Nixon had become President of the United States. Nixon was known for being against communism. But in 1971, he said the U.S. "must have relations with Communist China." His plan was to slowly pull U.S. troops out of South Vietnam. He still wanted to keep the South Vietnamese government in power. He thought this was only possible by improving relations with both Communist China and the USSR. He later visited Moscow to talk about arms control and the Vietnam War. But they could not agree on Vietnam. In the end, years of Soviet military aid to North Vietnam paid off. American troops' morale dropped, and they fully withdrew from South Vietnam by 1973. This led to Vietnam being united under communist rule two years later.

Sino-Soviet Relations

Soviet relations with China quickly got worse after Nikita Khrushchev tried to improve ties with more open Eastern European states like Yugoslavia and with the West. When Brezhnev gained power in the 1960s, China was in crisis because of Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution. This severely damaged the Communist Party of China and other ruling groups. Brezhnev, who was a practical politician and wanted "stability," could not understand why Mao would start such a "self-destructive" effort to finish the socialist revolution.

However, Brezhnev had his own problems with Czechoslovakia. Its big changes from the Soviet model led him and the Warsaw Pact to invade their ally. After the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, the Soviet leaders announced the Brezhnev Doctrine. This said the USSR had the right to step in if any communist country did not follow the Soviet model. This new policy increased tension not only with the Eastern Bloc but also with Asian communist states. By 1969, relations with other communist countries were so bad that Brezhnev could not even get five of the fourteen ruling communist parties to attend a meeting in Moscow. After the failed meeting, the Soviets concluded that "there was no leading center of the international communist movement."

Later in 1969, the worsening relations led to the Sino-Soviet border conflict. This split greatly upset Premier Alexei Kosygin. For a while, he refused to accept that it was permanent. He briefly visited Beijing in 1969 because of the rising tension. By the early 1980s, both China and the Soviets were making statements calling for normal relations. China's conditions for the Soviets were: fewer Soviet troops on the border, withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan and Mongolia, and an end to Soviet support for Vietnam's invasion of Cambodia. Brezhnev responded in his March 1982 speech in Tashkent. He called for normal relations. Full normalization between China and the Soviet Union would take years, happening only after the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, came to power.

Intervention in Afghanistan

After the communist revolution in Afghanistan in 1978, the new government made strict rules. This led to the Afghan civil war, with fighters called the mujahideen rising up against the government. The Soviet Union worried about losing its influence in Soviet Central Asia. A KGB report claimed Afghanistan could be taken in weeks. So, Brezhnev and several top party officials agreed to a full intervention.

Today, researchers believe Brezhnev was given wrong information about the situation in Afghanistan. His health was poor. Supporters of military action gained power in the Politburo by using false evidence. They suggested a smaller plan, keeping 1,500 to 2,500 Soviet military advisors and technicians in the country. These had already been there since the 1950s. But they disagreed on sending hundreds of thousands of regular army troops. Some believe Brezhnev signed the order without being told the full story. Otherwise, he would never have approved such a decision. Soviet ambassador to the U.S. Anatoly Dobrynin thought Mikhail Suslov was the real person behind the invasion, who misinformed Brezhnev. Brezhnev's personal doctor later said that Brezhnev, when clear-headed, actually resisted the full-scale invasion. Some in the Soviet military were against any active Soviet military presence in Afghanistan. They believed the Soviet Union should stay out of Afghan politics.

Invasion of Czechoslovakia

The first big problem for Brezhnev's government came in 1968. The communist leaders in Czechoslovakia, led by Alexander Dubček, tried to make the communist system more open. This was called the Prague Spring. In July, Brezhnev publicly said that the Czechoslovak leaders were "revisionist" and "anti-Soviet." Even though he made strong public statements, Brezhnev was not the one pushing hardest for military force in Czechoslovakia. Records show that Brezhnev was one of the few who wanted to find a temporary solution with the reform-minded Czechoslovak government. However, in the end, Brezhnev decided that he would risk growing problems at home and in the Eastern Bloc if he did not support Soviet intervention.

As pressure grew on him to "re-install a revolutionary government" in Prague, Brezhnev ordered the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia. Dubček was removed in August. After the Soviet intervention, Brezhnev met with a Czechoslovak reformer, Bohumil Simon. He told him, "If I had not voted for Soviet armed assistance to Czechoslovakia you would not be sitting here today, but quite possibly I wouldn't either." However, instead of bringing stability, the invasion caused more disagreement in the Eastern Bloc.

The Brezhnev Doctrine

After the Prague Spring was stopped, Brezhnev announced that the Soviet Union had the right to interfere in the internal affairs of its satellite states. This was to "safeguard socialism." This became known as the Brezhnev Doctrine. However, it was really just a restatement of existing Soviet policy. Khrushchev had used it in Hungary in 1956.

Later in 1980, a political crisis happened in Poland. This was due to the rise of the Solidarity movement. By the end of October, Solidarity had 3 million members. By December, it had 9 million. A public opinion poll by the Polish government showed that 89% of people supported Solidarity. The Polish leaders were divided on what to do. Most did not want to declare martial law, as suggested by Wojciech Jaruzelski. The Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc countries were unsure how to handle the situation. But Erich Honecker of East Germany pushed for military action. In a letter to Brezhnev, Honecker suggested a joint military action to control the problems in Poland. A CIA report suggested the Soviet military was getting ready for an invasion.

In 1980–81, representatives from Eastern Bloc nations met in the Moscow Kremlin to discuss Poland. Brezhnev finally decided on December 10, 1981, that it would be better to leave Poland's internal matters alone. He assured the Polish delegates that the USSR would only intervene if asked to. This effectively marked the end of the Brezhnev Doctrine. Even without a Soviet military intervention, Wojciech Jaruzelski eventually gave in to Moscow's demands. He declared a state of war, which was Poland's version of martial law, on December 13, 1981.

Public Image and Health

Cult of Personality

Russian historian Roy Medvedev noted Brezhnev's strong desire for ceremonial power. He was loyal to his friends and did not control corruption within the party. Especially in foreign affairs, Brezhnev increasingly made all major decisions himself. He did not always tell his colleagues in the Politburo. He purposely showed a different side of himself to different people. This led to a growing glorification of his own career. The last years of Brezhnev's rule were marked by a growing cult of personality.

He was well known for his love of medals. He received over 100 of them. In December 1966, on his 60th birthday, he was given the Hero of the Soviet Union award. This award came with the Order of Lenin and the Gold Star. Brezhnev received this award three more times to celebrate his birthdays. On his 70th birthday, he was given the rank of Marshal of the Soviet Union. This was the highest military honor in the Soviet Union. After receiving the rank, he attended a meeting of 18th Army Veterans. He was dressed in a long coat and said, "Attention, the Marshal is coming!" He also gave himself the rare Order of Victory in 1978. This award was later taken back in 1989 because he did not meet the requirements for it. A promotion to the rank of Generalissimus of the Soviet Union was planned for his seventy-fifth birthday. But it was quietly dropped due to his ongoing health problems.

Brezhnev's desire for undeserved glory was shown in his poorly written memoirs about his military service during World War II. These books treated minor battles near Novorossiysk as very important. Despite the book's weaknesses, it won the Lenin Prize for Literature. It was praised by the Soviet press. The book was followed by two other books, one about the Virgin Lands Campaign. Brezhnev's vanity made him the subject of many Russian political jokes. Nikolai Podgorny warned him about this. But Brezhnev replied, "If they are poking fun at me, it means they like me."

Following traditional socialist greetings, Brezhnev often kissed politicians on the lips. One famous occasion, with Erich Honecker, was painted as a mural on the Berlin Wall. The mural is called My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Love.

Health Challenges

Brezhnev's public image was growing while his health was quickly getting worse. His physical condition was declining. He had been a heavy smoker until the 1970s. From 1973 until his death, Brezhnev's brain and nervous system slowly got worse. He had several small strokes and trouble sleeping. In 1975, he had his first heart attack. When he received the Order of Lenin, Brezhnev walked unsteadily and mumbled his words.

According to one American intelligence expert, U.S. officials knew for several years that Brezhnev had severe hardening of the arteries. They also believed he had other health problems. In 1977, American intelligence officials publicly suggested that Brezhnev also suffered from gout, leukemia, and lung disease from years of heavy smoking. He was also reported to have a pacemaker to control his heart rhythm. Sometimes, he had memory loss, speaking problems, and trouble with coordination. According to The Washington Post, "All of this is also reported to be taking its toll on Brezhnev's mood. He is said to be depressed, despondent over his own failing health and discouraged by the death of many of his long-time colleagues."

After suffering a stroke in 1975, Brezhnev's ability to lead the Soviet Union was greatly affected. As his ability to make foreign policy decisions weakened, he increasingly relied on the advice of a group of hardline officials. This group included KGB Chairman Yuri Andropov, longtime Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko, and Defense Minister Andrei Grechko (who was replaced by Dmitry Ustinov in 1976).

The Ministry of Health kept doctors with Brezhnev at all times. They saved him from near-death several times. At this time, most senior officials of the Communist Party wanted to keep Brezhnev alive. Even though more and more officials were unhappy with his policies, no one wanted to risk new problems at home if he died. Western observers started guessing who would replace Brezhnev. The most notable candidates were Suslov and Andrei Kirilenko, both older than Brezhnev. Younger candidates included Fyodor Kulakov and Konstantin Chernenko. Kulakov died in 1978.

Last Years and Death

Brezhnev's health got worse in the winter of 1981–82. While the Politburo was thinking about who would take over, all signs showed that the sick leader was dying. The choice of the next leader would have been influenced by Suslov, but he died at age 79 in January 1982. Andropov took Suslov's place in the Central Committee Secretariat. By May, it became clear that Andropov wanted to become the General Secretary. With the help of other KGB associates, he started spreading rumors that political corruption had gotten worse under Brezhnev. He tried to create an environment in the Politburo that was against Brezhnev. Andropov's actions showed that he was not afraid of Brezhnev's anger.

In March 1982, Brezhnev suffered a concussion and broke his right collarbone. This happened while he was visiting a factory in Tashkent. A metal railing collapsed under the weight of several factory workers, falling on Brezhnev and his security team. Western news reported this as Brezhnev having suffered a stroke. After a month of recovery, Brezhnev worked on and off until November. On November 7, 1982, he stood on the Lenin Mausoleum's balcony. This was during the annual military parade and workers' demonstration celebrating the anniversary of the October Revolution. This was Brezhnev's last public appearance. He died three days later after suffering a heart attack. He was given a state funeral after five days of national mourning. He was buried in the Kremlin Wall Necropolis in Red Square. His tomb is one of twelve individual tombs between the Lenin Mausoleum and the Kremlin wall.

Leaders from around the world attended his funeral. His wife and family were also there. Brezhnev was buried in his Marshal's uniform with his medals.

Legacy

Brezhnev led the Soviet Union for a longer time than anyone else, except Joseph Stalin. He is often criticized for the long period of stagnation. During this time, major economic problems were ignored. The Soviet political system was allowed to decline. During Mikhail Gorbachev's time as leader, there was more criticism of the Brezhnev years. Some claimed Brezhnev followed a "fierce neo-Stalinist line." Gorbachev's discussions blamed Brezhnev for not modernizing the country and adapting to new times. However, Gorbachev later said that Brezhnev was not as bad as he was made out to be. He said, "Brezhnev was nothing like the cartoon figure that is made of him now." The invasion of Afghanistan was one of the biggest decisions of his career. It greatly hurt the Soviet Union's standing in the world and its internal strength. In Brezhnev's defense, it can be said that the Soviet Union reached very high levels of power, respect, and internal calm under his rule. These levels were never reached again.

Brezhnev has done well in opinion polls compared to other Soviet leaders in Russia. In a 2007 poll, most Russians chose to live during the Brezhnev era rather than any other period of 20th-century Soviet history. In a 2013 poll, Brezhnev was voted Russia's favorite 20th-century leader with 56% approval. In another 2013 poll, Brezhnev was voted the best Russian leader of the 20th century. In a 2018 poll, 47% of Ukrainian people had a positive opinion of Brezhnev.

In Western countries, he is most often remembered for starting the economic stagnation. This stagnation eventually led to the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Personality Traits

Brezhnev's main hobby was driving foreign cars. These cars were given to him by leaders from around the world. He usually drove them between his country house and the Kremlin. According to historian Robert Service, he drove with little regard for public safety. When he visited the United States for a meeting with Richard Nixon in 1973, he wanted to drive around Washington in a Lincoln Continental that Nixon had just given him. When he was told that the Secret Service would not allow this, he said, "I will take the flag off the car, put on dark glasses, so they can't see my eyebrows and drive like any American would." To this, Henry Kissinger replied, "I have driven with you and I don't think you drive like an American!"

Personal Life

Brezhnev was married to Viktoria Denisova (1908–1995). He had a daughter, Galina, and a son, Yuri. His niece Lyubov Brezhneva published a memoir in 1995. She claimed that Brezhnev worked to give special benefits to his family. These benefits included good jobs, apartments, private luxury stores, private medical care, and protection from legal trouble.

Honours

Brezhnev received many awards and honors from his own country and from foreign countries. Some of his foreign honors include the Bangladesh Liberation War Honour and the Hero of the Mongolian People's Republic.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Leonid Brézhnev para niños

In Spanish: Leonid Brézhnev para niños

- Attempted assassination of Leonid Brezhnev

- Bibliography of the Post Stalinist Soviet Union